The 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense was thrust into the mainstream early in 2016, when Beyoncé paid tribute to the revolutionary group during her performance of “Formation” at Super Bowl 50 in the San Francisco Bay Area. The pop superstar and her dancers were decked in leather costumes, with the dancers wearing characteristic black berets and the singer herself sporting crossed bandoliers. Not only did Beyoncé honor a defiant radical organization, she also flipped the gender script: While women accounted for two-thirds of the Party’s membership, the historic images we remember of Black Panthers in militaristic garb are of men.

“I did do a lot of cooking. Women had very specific roles in the militant movement.”

Much of the reverence—and controversy—around the Black Panther Party centers on its early male leaders, Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, and Eldridge Cleaver, respectively 24, 29, and 31 when the Party launched in Oakland, California. Those three young men were both well-read intellectuals in the black nationalist movement and hard-edged revolutionaries, two of whom had recently served time in prison: Newton had done six months for assaulting a black acquaintance with a steak knife, and Cleaver served eight years on rape charges. The assassination of black nationalist trailblazer Malcolm X on February 21, 1965, in New York City compelled Newton and Seale to take a more active stance against white supremacy: On October 15, 1966, the two formed the Black Panther Party as an armed patrol against police brutality toward the African American community, which led to headline-grabbing shootouts in Oakland in 1967 and ’68.

The cover of Judy Juanita’s novel Virgin Soul.

The legacy of the Black Panther Party, however, goes far beyond its complicated, iconoclastic leaders, as illuminated at the Oakland Museum of California’s exhibition, “All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50,” which runs through February 12, 2017. The organization, which put out an international newspaper “The Black Panther Community News Service” every week for a decade, was a game-changer, forever altering how African Americans saw themselves. In every issue, the newspaper published its Ten-Point Program, which starts with “We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.” Behind the scenes, thousands of Black Panther volunteers ran 60-some social programs that fed poor children breakfast, gave away bags of groceries to hungry families, transported sick and disabled people, provided free health care, offered legal aid and drug counseling, and more. The hard work of women was the lifeblood of these so-called “survival programs.”

One woman doing such work was Judy Juanita—a playwright, novelist, and poet who currently teaches at Laney College in Oakland. She met Newton and Seale while attending Oakland City College between 1963 and 1966, and joined the Party at age 20, after she transferred to San Francisco State University across the bay. In 2013, she published Virgin Soul, a novel incorporating her experiences as a Black Panther living in San Francisco, which was also the center of the free-love and hippie movements. Her protagonist, Geniece Hightower, has a lot in common with her younger self, including being named editor-in-chief of the Black Panther newspaper for a brief time in the spring of 1968. And like Juanita, Geniece spends much of her time in the kitchen: In the foundational days of the Party, women like Juanita did the grunt work and “stood behind black men.” After Juanita began to focus on her own family and career in 1969, the Party newspaper declared men and women equal and Chicago leader Fred Hampton condemned sexism. That year, Hampton also forged alliances with revolutionary white and Latino organizations, before he was killed in a police raid in December.

Juanita’s novel is a fascinating inside look of the early years of the Black Panthers, as told by someone close to the organization’s center but never in the spotlight. Recently, Juanita chatted with me over the phone and explained how Geniece’s story related to her real life as a Panther.

Top: From left, black activists T.C. Williams, Judy Hart (now Judy Juanita), Ron Bridgeforth, and Jo Ann Mitchell at San Francisco State University in 1967. (Courtesy of Judy Juanita) Above: Beyoncé’s dancers raise their fists in solidarity with the Black Panther Party backstage at Super Bowl 50 in February 2016. (Via Twitter)

Collectors Weekly: The Black Panther Party started at Oakland City College in 1966, when you went to school there. Can you tell me about the pre-Panthers scene?

Juanita: It was very much like I described in Virgin Soul: a convergence of students from many different backgrounds. There was a great mix of ethnicity even then—white, black, and Chinese. Some students, frankly, had flunked out of UC Berkeley and came to Oakland City College—which later changed its name to Merritt College—to regroup and bring their GPAs up to an acceptable standard. A lot of students were there because it was cheaper. You could transfer as many as 70 units to the four-year colleges, which was a popular choice. It only costs $2 a semester at that time, and UC was $300 a year.

The Attorney General of the State of California during the Reagan administration, Evelle Younger, called Oakland City College “a hotbed of radicalism.” And it was. All kinds of radical groups were there, from Students for a Democratic Society to the W.E.B. Du Bois Club. Young people would hang out on campus—which was then on Grove Street, which is now Martin Luther King, Jr., Boulevard—whether they went to school there or not. It was a very exciting scene, with tables lined up and tons of soapbox orators all along the way. When I go to college campuses now, I’ll see a whole row of people selling jewelry and artifacts. I’ll marvel, “Wow, 40 years ago, those tables would have been promoting radical organizations, like the Free Speech Movement or the Sexual Freedom League.” So many people met at City College, where we formed friendships and marriages and joined forces during that period.

Bobby Seale, left, and Huey P. Newton wear berets and brandish guns on a Black Panther Party political poster. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: At the time, what was your personal experience of racism?

Juanita: I wouldn’t have used the word “racism” to describe my experiences. Back then, the focus was on civil rights, like getting blacks integrated into jobs and public accommodations, etc. As a young woman, I knew that I faced walls and glass ceilings. While I knew that, I looked at racism as more of problem happening down South and ignored the reality that it was going on here in the Bay Area as much as any place else. Racism has been delineated much more clearly in the past, say, 20 or so years.

“We came to campus armed with our theories and our pieces. So guns were both literal and metaphoric. They were symbols of defiance.”

Looking back, I do see it in my life. When I was a high school senior, I got the top journalism student honor at my school, Castlemont. My college counselor was white, and her son, who went to school with me, was white. I visited her to ask about getting a scholarship to University of Southern California, which had a great reputation as a journalism school. She said, “No, you can’t go there. You would never be able to get in there.” And it was just cut and dried. Meanwhile, her son got into USC. I’m not going to disparage his abilities, but she made sure he got in.

The Bay Area was very integrated in many senses, but it was also very segregated in others. At that time, Oakland was William Knowland’s town. Knowland was a former U.S. senator who became the publisher of the “Oakland Tribune” newspaper. Thanks to Knowland, back then, East 14th Street was the real estate red line, and blacks found it very hard to move above East 14th Street until the late ’60s, when there was white flight from the city.

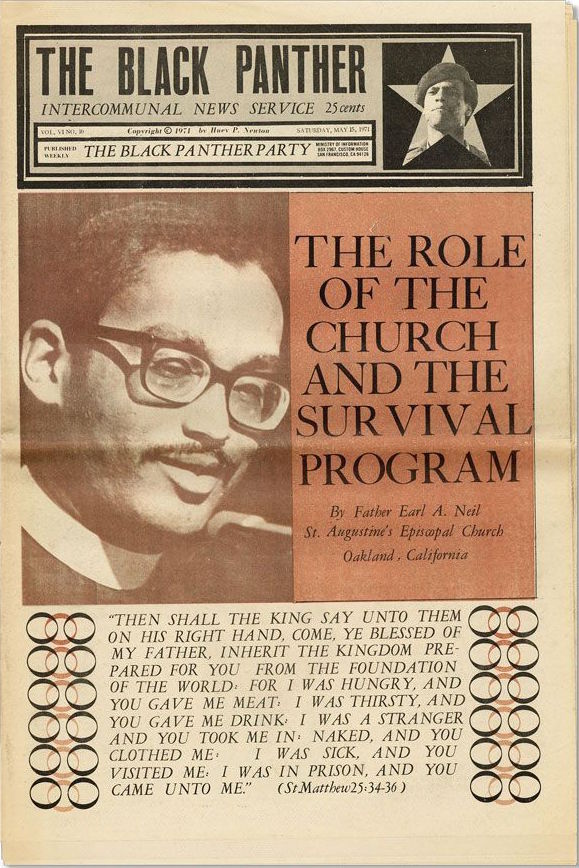

The May 21, 1971, issue of the Black Panther newspaper reveals the more nurturing side of the party. (Via eBay)

There were five high schools in Oakland, and McClymonds was the only school that had mostly black students because of its West Oakland location. The way Oakland school districts were sliced up, the other four high schools at the time had students from both the wealthy white neighborhoods in the hills and the poorer black neighborhoods in the flat areas. The powers that be decided to create Skyline High School in 1962, the year before I graduated from high school. They made the Skyline school district boundaries so that they contained the upper-middle class hills neighborhoods and effectively re-segregated the schools again. But because of the eventual effects of Brown v. Board of Education, the movement to bus students grew very strong in the ’60s, so Skyline became integrated regardless. That was the atmosphere of desegregation, segregation, and reintegration that was going on when I was a young person.

However, the radical edge to Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco cut into the status quo. You had all these different justice movements here in the Bay Area, like the drug-rehabilitation group Synanon. Alcoholics Anonymous had its first West Coast meeting in San Francisco. The Mattachine Society, the movement to prevent gay people from being arrested, started in San Francisco.

Collectors Weekly: Early in the book, Geniece attends a black-history talk by a white professor when Huey Newton and Bobby Seale come in with guns.

Juanita: Yes. That only happened in the book. I remember Huey and Bobby coming into the classroom, so the addition of guns may have been fictional liberty. Oakland City College was the birthplace of black studies. At that point, Huey and Bobby were leaders in the college’s Afro-American Association, which advocated for a black history class, and their work was the reason this professor, Rodney Carlisle, was hired in the first place. He’d just gotten his Ph.D., and he was so boyish.

This image, circa 1969, became an icon of the “Free Huey” movement, which demanded that Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton be released from prison, where he was being held in connection to the shooting death of Oakland police officer John Frey. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, All of Us or None Archive)

Collectors Weekly: What led to the formation of the Black Panther Party at Oakland City College?

Juanita: In Alabama, there was a political party, Lowndes County Freedom Organization, that was known as the Black Panther Party, because of its panther logo. An activist in West Oakland named Mark Comfort took a California delegation to Lowndes County to protect black people exercising their right to vote for the first time after the Voting Rights Act passed in 1966, and he came back with permission to use that logo and name.

The Black Panther Party started in Oakland in October 1966 as an idea for a civilian police patrol. Throughout all the protests and race riots of the ’60s, rioters, civil rights activists, and militants were calling attention to the abuses of police power. The Black Panthers called attention to this abuse in a much more formalized way with their party platform, their activist movement, and particularly their appearance in Sacramento, when 30 Black Panthers carried guns into the State Capitol building on May 2, 1967.

Collectors Weekly: Now, 50 years later, we’re seeing echoes of this sentiment as Black Lives Matter activists draw attention to police brutality.

Juanita: Yeah, people are seeing we have given the police far too much power in this country. In other democratic societies, the police don’t have that much power. But in the U.S., there’s some sort of alchemy between police power and racism. That’s so unhealthy and so tragic.

Black Panther leader Bobby Seale inspects bags of groceries the organization has prepared to hand out to impoverished families in Oakland, on March 31, 1972. Photo by Howard Erker. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, the “Oakland Tribune” collection)

Collectors Weekly: When you were part of the Black Panther Party, what were the group’s objectives?

Juanita: The objectives were very clear-cut. They were repeatedly broadcast and put into the newspaper every week—the Ten-Point Program. We learned in political education classes that one of the tasks of the Party, the vanguard of the revolution, is to show the people the way. It’s not as though the Black Panther Party alone could stand up and fight the police. It was to show the community we don’t have to let an occupying army come into our communities and take over and slaughter us.

“Instead of being frustrated, people had an attitude of resistance. The government was the antagonist.”

The media put a lot of emphasis on the guns, but there were many community-service programs, like the free health clinic and Breakfast for Children program. The aim of these social programs was to show the community and the government, “This is what a just society should do.” In a just society, particularly one that is as wealthy as this one, no child should be going to school hungry. Now, the government funds breakfast programs in schools, but it wasn’t doing so back then.

When the Black Panther Party launched these programs, the United States didn’t have food stamps. We created more than 60 programs. You know how they would occur? People would go up to Bobby and say, ‘We have this problem where people can’t see their family in prison.” Bobby would say, “I think that we should have a visitor run. Go do it. You’re in charge of it.” That was incredible and empowering. So the Black Panther Party also started taking families to visit inmates in San Quentin prison. The person in charge would get a bus and then let word out in the community, “We’re going to meet at X place, and we’re going to take you to visit your family member in San Quentin.”

Father Earl A. Neil of St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland supported the Black Panthers’ first “survival program.” (Via eBay)

In the ’60s, people were looking at end-of-the-world scenarios with the atomic bomb and the Cold War. “Tricky Dick” Nixon got elected during this period, and the Vietnam War was ongoing. Women who were graduating college, Hillary Clinton’s generation, were saying, “I’m not going to have any children because I don’t want to bring a child into this world.” That was the most popular type of valedictorian speech at the women’s colleges at the time.

“At that time in the movement, women who questioned men were called ‘difficult.'”

People had a very anti-government sentiment—we weren’t expecting the government to respond. No, all of those changes happened gradually over the next couple of decades. They didn’t happen right away. Instead of being frustrated, people had an attitude of resistance. The government was the antagonist. The American counterculture, we were the protagonists.

That’s really what the ’60s were about: We were good students. We said, “Wait a minute, something’s not right here. We’re not getting the complete story.” The desire to get the complete story came from the Civil Rights Movement and then the Vietnam War. Blacks wanted to investigate, “What’s happening with our civil rights?” And the white kids were coming out of the “Mad Men” era and saying, “Something’s not right here. We’ve been carrying on war like this continuously, using the great phrase ‘Manifest Destiny,’ and we’ve been slaughtering people since forever.” After World War I and World War II, we could question, “Wait a minute, what was so great about the war? What about the people who died?”

We weren’t expecting to make nice with the government, but that’s kind of what happened. The electoral politics in the ’70s brought a lot of black congressmen into office, like Ron Dellums from Oakland. But that was the ’70s—a whole other era.

Protestors rally at the Alameda County Court House in Oakland in support of Huey Newton, who was on trial at the time for the fatal shooting of a police officer, in 1968. Photo by Lonnie Wilson. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, the “Oakland Tribune” Collection)

Collectors Weekly: Geniece is attracted to the intellectuals who are preaching cultural nationalism on Grove Street, but she seems put off by their arrogance.

Juanita: Even though she’s questing and she wants to find out what’s going on, she just came out of a very strict environment with her aunt, uncle, and grandmother. Even though her parents aren’t there, she’s been parented. She’s looking for freedom, and she can pretty much see that the nationalists want to control her. And she doesn’t want to be controlled. Her quest is to get an education.

Collectors Weekly: What I enjoy about the character is that she’s always questioning everyone.

Juanita: Yes! At that time in the movement, women who questioned men were called “difficult.” Geniece is a rebel. She’s going to rebel wherever she is. If you say “yes,” she’s going to say “no.”

“We were so silly and so young, and we survived because we didn’t really know the true danger that we were in.”

In my life, my much-younger sister joined the Black Panthers nine years after I did. My mom used to call us her nine-year delayed twins. Once when we were having an argument, a sister argument, she said, “I don’t think you 100 percent internalized the Black Panther Party principles.” And I said, “I don’t 100 percent internalize anything. I have my own set of principles and standards.” So Geniece was like that part of me—she’s not going to buy into everything. She’s not going to buy in 100 percent, and I think that makes her an interesting character. She’s listening, an observer.

And that’s healthy! I tell my students, “In dictatorships, the first people who disappear or the first people who are attacked are the college professors.” Then I ask them, “Why is that?” and it takes them a while to figure it out—but not too long. They say, “You’re making us think.” I say, “Yes. But you don’t need people to make you think. It’s up to you.”

Several Black Panther Party propaganda posters by illustrator Emory Douglas show women with guns. The reprint of a 1971 poster, at left, reads: “Listen to them pigs banging on my door asking for some rent money … They should be paying my rent.” (Via eBay) The 1969 poster on the right says: “Afro-American solidarity with the oppressed People of the world.” (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, All of Us or None Archive)

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me about your relationship with guns and what they meant to you?

Juanita: Guns were empowering. Guns are both literal and metaphoric in the book. In my life at that time, I carried a gun. I had been raised in a very religious household with no guns. But when I was in the Party, I discovered I liked marksmanship, and I did well at the range. And I did carry a small gun in my purse, a .22, for a while, not long. I understood the power of the gun because I had to conceal it. I actually worked at the post office for about three months, and I would have the gun in my purse. I didn’t even realize, perhaps, how dangerous that was. I don’t know. Maybe I did. Because I was involved with a brother who was very up on guns, I began to realize that guns had some status value: They cost a lot of money, and there was a lot of talk about spending money for guns. On the range, I could see some of these people were not all involved in the movement, but there they were. I would hear them talking about the relative merits of this versus that gun, just like guys with their cars.

But within the party, of course, and within the Black Student Union, we came to campus armed with our theories and our pieces. So guns were both literal and metaphoric. We had them. We learned how to clean them. We learned how to operate them. We learned where to store them. We learned how to carry them in cars so that if we got stopped by the police, we would be legal. They were symbols of defiance.

Eldridge Cleaver composed this famous 1966 image of Huey Newton, shot by Blair Stapp. Newton holds a spear and a gun while surrounded by Africana. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, All of Us or None Archive)

Collectors Weekly: What is your take on Huey Newton as a leader?

Juanita: I’d say, great man, great flaws—that’s kind of it. Great people often have great flaws. I think that he, Bobby Seale, and Eldridge Cleaver captured the zeitgeist of the time. That’s a particular genius in and of itself. I’d say changing the language and the way black people thought about themselves was extremely remarkable and of far more value than what the gun did. Jean-Paul Sartre talks about the oppressor, and he says when the oppressed learn the language of the oppressor, then they can use it to tear down the house that is imprisoning them and break the chains.

For centuries, black people have been referred to in American society as “coons” and “baboons,” and even we see that today, like what happened with Leslie Jones, the “Saturday Night Live” comic. These derogatory terms were used throughout centuries of slavery to justify enslaving Africans. Post-slavery, the slurs continued to promote the oppression of black people, by belittling and demonizing them because of physical characteristics. Then, in 1966, the Panthers, Huey and Bobby, came up with the term “pig” to describe police behavior. The genius was that in one fell swoop, the Panthers put into the lexicon a word that characterized wrongful behavior.

Collectors Weekly: Another historical figure in your book is Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. How did he influence you?

Juanita: I attended his big rally at UC Berkeley in 1966. Shouting “black power” at the rally was big fun. I was young, and I was exercising my right of assembly and free speech. From afar, I had been watching all of these civil rights workers from SNCC and other Southern organizations in the news helping people register people to vote. The situation was very perilous, and many people gave their lives for that. So I was very impressed by SNCC, and many of us here were following their activities.

Later, SNCC tried to expand its base to the Northern colleges but it didn’t catch on. However, I did meet Stokely Carmichael when he and several of his field marshals, as they were called then, came to San Francisco State and spoke. Actually, for a brief period of time, he was a member of the Black Panther Party and had a big role in it.

Stokely Carmichael expounds on his “black power” concept in 1966. This image first appeared in the 1967 Michigan State University yearbook, Wolverine. (Via WikiCommons)

Collectors Weekly: How did the Black Panther Party fund its social programs?

Juanita: The funding, amazingly, came from all over. When I was editor of the Black Panther newspaper, my roommates would be at the office with me, opening the mail. We’d get big checks from huge celebrities and then $10 checks from Joe Schmoes, who’d write, “I like what you guys are doing. Here’s some money.” When the Panthers passed a bucket at rallies, all different kinds of people would be putting money in.

Collectors Weekly: It also sounds like it took a lot of elbow grease.

Juanita: Totally. Everybody sold the Black Panther newspaper. We’d finish working on the paper, then get out and sell it. That’s why I call the book the story of the female foot soldier. It was the little people, far more women than men. The pictures of the guys in the black berets and black leather standing in military formation have become the popular images, but they belie the truth, which was the vast majority of members were women. It’s just that often we were behind the scenes, and that’s what I try to give substance to in the book, the behind-the-scenes work.

Collectors Weekly: Speaking of being behind the scenes, in the book, Geniece’s first boyfriend, Allwood, hosts political education classes in her apartment—and she does all the cooking.

Juanita: Yeah, I was trying to make a point—and I did do a lot of cooking. Women had very specific roles in the militant movement, and it took a bit for it to morph into something else. But I was writing about things that were happening in ’64 through ’68.

Activist Elaine Brown, also a singer, released her second socially conscious funk/soul album in 1973. From ’74 to ’77, she was the first female leader of the Black Panthers. Listen to her songs here. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: After two years of junior college, you transferred to San Francisco State, which is where the Experimental College furthered the black studies cause.

Juanita: Experimental College classes were often held on the lawn, in the commons, and in the cafeteria, in addition to being at certain classrooms. Sometimes they were taught by TAs, sometimes by off-campus speakers, and sometimes by students, but it wasn’t just anyone. The teachers were people who had gained hands-on expertise. Have you heard of the movement called the Diggers? They served free food in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in San Francisco. So maybe they would teach a class on their nutrition plan. It wasn’t crazy or haphazard, just innovative.

“The pictures of the Black Panther guys in the black berets and black leather standing in military formation have become the popular images, but they belie the truth.”

The point was that none of this was happening in the regular college. For example, the Indian yogi movement, which was worldwide, wasn’t being taught. So somebody—maybe it was the Maharishi or one of his devout followers—would come and give an Experimental College lecture on it. People wanted to know, “How do you adhere to this practice?” I took a lot of these classes, and I loved them. They were forerunners of black studies, Africana studies, LGBTQ studies, women’s studies, and American studies.

The Black Student Union at SF State with the Third World Liberation Front, organized a student strike on campus to expose the racism on campus and calling for black studies and open enrollment. It would turn out to be the longest student strike in U.S. history, four and half months, in 1968. It forced the university to launch both Black and Ethnic Studies program. It changed San Francisco State and higher education all over the country. We changed the college experience from being about the study of dead white men to the study of many different cultures. Educators began looking at all of the disciplines in a different way—from dance to geography to history to science.

Collectors Weekly: In your book, it’s fascinating how the hippie culture intersects with the black power movement.

Juanita: Really, that’s a function of geography. Do you know San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury and Fillmore districts? They’re contiguous. Part of the stew or the mix came from the closeness of the neighborhoods. At San Francisco State, the on-campus housing was looked at as square—so students wanted to live in the Haight or the Fillmore. And if you lived in those neighborhoods, you got everywhere on foot. It was big fun, walking around San Francisco.

So that made also for a closeness, and proximity breeds association. Whether we were white or Hispanic or black, we knew each other. The Third World Liberation Front met in apartments all over the Haight and the Fillmore.

Black Panthers stand in front of the Alameda County Court House on July 14, 1968, the first day of Huey Newton’s murder trial. The men in front wear typical Panther-style jackets and berets. In the background, the women sport natural hairdos and slinky Mod skirts. Photo by Lonnie Wilson. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, the “Oakland Tribune” Collection)

Collectors Weekly: How did fashion serve as a political statement at that time?

Juanita: First of all, remember, girls weren’t allowed to wear pants to high school; we had to wear skirts. So as soon as we got to college, it was jeans, jeans, jeans. We’d let our jeans fray through. All of the popular fashions, like tie-dyes, were very cheap. When you had a pair of jeans getting old, you cut the jeans open and put a piece of fabric in between the legs, making a jean skirt. Then the Mod look from London came along, which encouraged us to wear really short skirts and big, flashy, chunky earrings. We didn’t want to go back to the ’50s look, where women had to wear girdles. My mother put on her girdle every morning, and I never wanted to do that.

“With the term ‘pig,’ in one fell swoop, the Black Panthers put into the lexicon a word that characterized wrongful behavior.”

In the ’60s, fashion followed function. If you were out at a protest rally, or you were running in a demonstration, you couldn’t be all that cute. Everyone started growing their hair longer—men and women, white and black. When you started wearing an Afro, it didn’t seem to go with a three-piece suit. An Afro needed something looser, something groovier.

Getting your ears pierced was a big deal, and it was very cheap. In the little earring shops, you would buy three pairs for $10, and then they’d pierce your ears for free. For our parents, getting your ears pierced was akin to getting a tattoo now. It was forbidden. “You pierced your ears? Oh, my gosh, no!”

Collectors Weekly: In the book, Geniece gets involved in poetry and theater. Is that something you did as well?

Juanita: Oh, yeah. I was a poet, and got involved in theater, as part of a black arts and culture troupe. Today, the black arts movement is saying that it was the cultural arm of the black power movement. At the time, as I detail it in the book, there was a cleavage, a demarcation between the two. Huey even said put down the pen and pick up the gun. That said, one could not have existed without the other because each was changing consciousness on many different levels.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me a little bit about the Black House in the Fillmore?

Juanita: It was an actual place, in a Victorian on Broderick Street in San Francisco. After Eldridge Cleaver was released from prison in December 1966, he took up residence in the Black House. He and a poet named Marvin X were in charge there, and it was a wonderful, marvelous place. Great cultural events went on every day—every day!—from poetry readings to jazz concerts to political education classes. It didn’t last very long—maybe a year or so. When I was going to San Francisco State, I lived four blocks from the Black House, so my roommates and I would walk over in the evenings.

Collectors Weekly: In the book, when Geniece first goes there, the men keep pushing her toward the kitchen.

Juanita: That’s fictional, but I wanted to indicate at that time, the role of women was circumscribed. That reflects what was going on in society.

Eldridge Cleaver’s wife, Kathleen Neal Cleaver, was featured on the December 2, 1971, cover of “Jet” magazine. (Via Pinterest)

Collectors Weekly: Can you talk about how the concept of free love intersected with black power?

Juanita: I always like to emphasize that in the ’60s, women had control of their reproductive freedom for the first time in history, due to the advent of the birth control pill. In history, that’s the first time that women could say, “No, I don’t want a baby,” and still have sex. An interviewer at KPFA asked me, “Wow, didn’t the men take advantage?” And I said, “Come on now, we were all in our 20s, we were all young, and sex was free for the first time.” You didn’t have to make sex a big get-married-to-you deal, so there was a lot of experimentation.

“In a just society, particularly one that is as wealthy as this one, no child should be going to school hungry.”

Nobody was holding a gun to my head, nor any of my friends’ heads, and making us have sex with them. Maybe other women cowed to sexual pressure. But those of us who had a voice and were consequently known as difficult would say, “No, I don’t want to go to bed with you; I go to bed with whom I choose to go to bed with,” or we just said, “Nuh-uh!” One of my friends’ favorite phrases was “I’m not going for the okey-doke,” which meant jumping in bed with a guy just because he wanted you to. She’d come home, and we’d say, “Did you go for the okey-doke?” We had sexual freedom, but we had to stand up and assert ourselves.

At the time, I think every woman and man—and gay man and lesbian—had the experience of enjoying the period of sexual freedom, until your heart gets involved. Your heart gets broken, and then it’s not so free anymore. Even when you don’t have to pay the consequence of birthing a child, there are other consequences like feeling betrayed or losing trust or losing your faith in humankind because of a romance gone sour. Despite all the drama, many long-lasting relationships, including my own marriage, came out of that time.

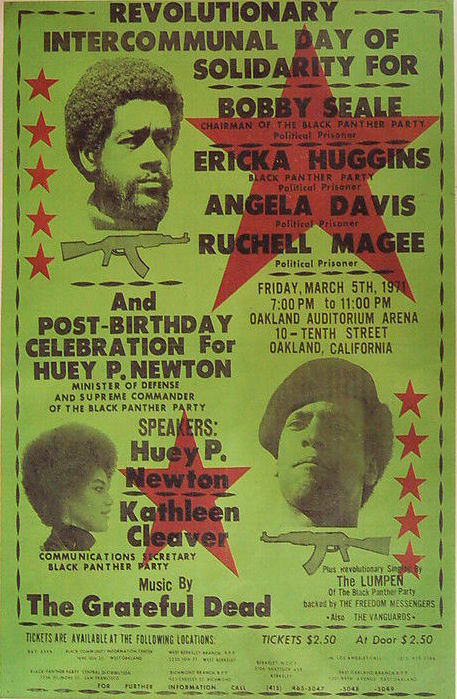

In 1971, psychedelic rock band The Grateful Dead played an Oakland rally for Black Panthers Bobby Seale, Ericka Huggins, Angela Davis, and Ruchell Magee, all of whom were in jail. Huey P. Newton and Kathleen Cleaver spoke at the event. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: In Virgin Soul, you talk a lot about colorism. Can you tell me the impact of this form of discrimination had on you in the ’50s and early ’60s?

Juanita: Colorism—meaning one’s color affected one’s destiny within the black community, and people of lighter complexion received preferential treatment—was big in the Bay Area black community. And my students at Laney College tell me it still is. The Oakland branch of an organization called Jack and Jill of America, which was very bourgeois, had that emphasis on color. The black sororities at that time had color preferences, too.

Collectors Weekly: In the book, even the revolutionary Black Panthers seem to give light-skinned women like Kathleen Cleaver and Elaine Brown more access to power.

Juanita: I think to the extent that it happened it reflected the morés of black society at that time. I would say I don’t think it was a mistake that Kathleen, Elaine, Ericka Huggins—and even Angela Davis, if you want to go that far—were all fairer-skinned. They were beautiful in a more acceptable way. And when I say acceptable, I don’t even mean acceptable just to a white mainstream society, but maybe, at that point, more acceptable to blacks also. It was a while before Cicely Tyson emerged in the mid-’70s to become an icon of beauty for black women. Some ideas take a long time to take hold. So the idea of “Black is Beautiful” was being expanded in the late ’60s, but it took a little while longer for it to become manifest in many areas of society.

A Black Panther newspaper from July 1969 features artwork by Emory Douglas depicting an “Avaricious Businessman” rat eating gold and “Black Capitalism.” (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: Even though you were mostly relegated to working behind the scenes, you were named editor-in-chief of the Black Panther newspaper?

Juanita: For a short period. After Eldridge was imprisoned in 1968, Huey personally appointed me editor-in-chief of the paper. A few of us were listening to a tape recording Huey made in prison at Mosswood Park in Oakland when it happened. I wrote about it in Virgin Soul, and yes, it did occur. On the tape, he said, “Make Judy Hart the editor-in-chief of the paper. I know her from her work at Oakland City; she’s a together sister.” My boyfriend at the time—who became my husband—our eyes just nearly popped out of our heads. I had no idea what it meant to be the editor-in-chief, and then I found out, “Oh, you’re going to take all of this stuff and somehow work it into the paper.” And there were tons of stuff—press releases to make into articles as well as Huey’s and Eldridge’s manifestos. It was amazing.

“In dictatorships, the first people who disappear or the first people who are attacked are the college professors.”

Frankly speaking, over the years, there were many editors-in-chief of the paper, but there was no doubt ever that Huey, Bobby, and Eldridge, or the central committee, were determining the content and the direction of the newspaper. Before being editor-in-chief, I was on the paper’s staff, where I worked with Eldridge at length as well as the Black Panther artist Emory Douglas.

Working for the paper was very much like how I described it in the book. First of all, it was nonstop. That was my first experience taking bennies, or Benzedrine pills, because we stayed up often for three days and nights in a row, putting the paper together to make that deadline. That was wild and crazy in and of itself. When you’re young, you don’t think about consequences. Taking medications that allow you to stay up is a time-honored way to get more done than you could ordinarily. Now, the kids use Red Bull.

But radical movements depend on young energy. Billy Jennings, the Black Panther archivist, reminds folks that we were all 17, 18, 19, 20 at that time. We could do that. You have that kind of energy then.

A June 1971 issue of the Black Panther newspaper addressed the grim housing situation some African Americans faced. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: But you didn’t get to do a lot of writing for the newspaper?

Juanita: No. I was very surprised because I hadn’t been an editor before I joined the paper. I had only been a journalist and a writer. So to sit down and then be given all of these position papers and articles from international thinkers like Bertrand Russell in the United Kingdom, it was quite an experience. I hadn’t planned on it. You have to remember that Huey, and then Eldridge, had a lot of time to sit down and write because they were in prison. Position papers would be coming from them all the time.

George Mason Murray was the Minister of Education for the Black Panther Party. George and I knew each other from way back; we went to Castlemont High School in Oakland together. When I transferred to San Francisco State, I ran into George again. We became very good friends before we even got involved in anything, just friends who talked and walked to classes all the time. He’s extremely intelligent—he got a Ph.D. from Stanford. George and I became active in the Panthers together. At a certain point, George became the face of the party, and a lightning rod for politicians to attack. The joke for me was George’s handwriting was practically chicken scratching, and I spent hours and hours transcribing George’s writing.

Black Panther artist Emory Douglas created this 1967 image of H. Rap Brown, a chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Community, who became a leader of the BPP when the two groups formed a brief alliance. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, All of Us or None Archive)

Collectors Weekly: What happened to the Party after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.?

Juanita: That galvanized the movement and melded all the factions of the Civil Rights Movement together because of the ultimate sacrifice that Martin Luther King, Jr., made with his life. It showed everybody the naked use of violence and power in the United States. If John F. Kennedy’s assassination hadn’t done that, then five years later, the double blow of Martin Luther King’s and then, a few months later, Bobby Kennedy’s assassination revealed that, as H. Rap Brown liked to say then, “Violence is as American as cherry pie.” It exposed the horribly violent underside to American society.

Collectors Weekly: After the assassination in the book, Geniece is on the run with Bobby Seale. Did that happen to you?

Juanita: Yes. That was one of the most harrowing nights of my life, a long run through the night with Bobby from safe house to safe house. My roomies very frankly went through far more, but I happened to get caught up in it that night. We heard the police were plotting to take out different Black Panther leaders, and I’ve since seen police records documenting that plan. There were many urban revolts after Martin Luther King was killed. There was the possibility that it might happen in Oakland also, and the Panthers averted that, discouraging rioting.

This April 1971 issue of the Black Panther newspaper commemorated the third anniversary of Li’l Bobby Hutton’s death. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: How were you affected when 17-year-old Li’l Bobby Hutton was killed two nights later, after police had cornered him and Eldridge Cleaver?

Juanita: Well, it was very sad. It had a sobering effect on me. I was very young, 21, and up until that point, being in the Party had been daring, exciting, and fascinating. Celebrities were involved, and there was so much going about, going here, going there, doing this, doing that, picking up this, picking up that. It kept me busy. It wasn’t until Bobby died that I realized, “This is extremely serious, and you could die in a minute because of your activity in this.”

My friends—my roomies and I—we were full of humor. We were so silly and so young, and we survived because we didn’t really know the true danger that we were in. In the book, the character of Dillard reflects one of my boyfriends at the time who kept saying, “Do you know what you’ve gotten yourself into?” He wasn’t buying any of it. When Bobby died, the scope of it really hit me.

Collectors Weekly: In the book, you talk about Geniece being aware that the Feds are following her and being a little bit blasé about it.

Kathleen and Eldridge Cleaver with their infant son, Maceo, pose in front of an FBI “Wanted” poster on the press book for the 1969 Algerian documentary, “Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther.” Eldridge Cleaver had fled to Algeria to avoid murder charges in California. (Via eBay)

Juanita: Yeah, we were, always. We knew our phones were tapped, and we were aware of it. That wasn’t unlike many other radicals in the Bay Area. It wasn’t unusual, and it wasn’t anything that anybody was unduly afraid of. As a matter of fact, it was almost like a badge of honor.

It wasn’t so much that you were important, as you were a threat, because they followed our parents. When I brought in that section in the book on Geniece visiting her aunt and uncle, I say each parent, each family gave one member to the revolution: Our parents supplied us with cars, books, money, food, clothing to help the cause. The FBI’s COINTELPRO books had many of our parents’ names and house addresses listed because they participated in that way. I had an aunt who let us have meetings at her house, and her name and her house number are in there. It was just, “Is this person aiding and abetting in any way?”

The constant tracking gives way to not paranoia but awareness that if you were black, you were a target. When Angela Davis was on the run after Jonathan Jackson and George Jackson were killed in a shootout, then any black woman throughout the United States who was fairer-skinned and had a big natural—which was the fashion then—was a danger and was often apprehended or stopped by the police. That is just ridiculous. But if you’re black, you’re suspect.

Collectors Weekly: Clearly, we’re having that same problem today.

Juanita: Yeah, as it’s now called—which it wasn’t back then—”racial profiling.”

Collectors Weekly: For me, the most startling passages in the book are when Geniece participates in seemingly random acts of violence, like when her lover Bibo punches a man and robs him.

Juanita: The Black Panther Party used to refer to people like Bibo as “jackanapes,” but there’s also the Marxist term, “lumpen proletariat,” which refers to the people at the bottom of society. They’re the people who then have to do whatever they have to do to survive, which often means illegal, illicit activities—robbing, stealing, survival by whatever means. Both the Nation of Islam and the Black Panther Party distinguished themselves from the more middle-class organizations like the NAACP and CORE by appealing to and recruiting street brothers and brothers in prison, people at the most dispossessed points in society.

Oftentimes, we would learn through studying political education, studying Marxism, that the lumpen bring those qualities with them. And through political education, they have to learn not to do those things. So, at that point, the book really shows Bibo’s character. And it also reveals her character because she’s fallen in with that and she doesn’t feel guilty about it.

It takes a long time for her to realize it. The book is about purity and impurity. She starts out at a certain pure point, and she becomes defiled, if you will. She allows it to happen, and she has to get a grip on it and understand it and see it for what it is.

Emory Douglas poster, 1969: “Only on the bones of the oppressors can the people’s freedom be founded—only the blood of the oppressors can fertilize the soul for the people’s self-rule. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, All of Us or None Archive)

Collectors Weekly: At the end of the book, Geniece starts to separate herself from the radicalism. Is that something that happened to you, too, in the late ’60s?

Juanita: No, not really. I just had to end the book. I’m sure you can tell from our conversation I still have a lot of those interests. I did, however, grow up, and growing up means that you choose how you’re going to be an adult. I got married in June of 1968, and a year and a couple of months later, I had a child, who became the focus of my life. Five days after I had my son, I finished my B.A. degree, and then five days later from that, I was offered a teaching job, becoming the youngest faculty member of the nation’s first Black Studies department.

Becoming a teacher, mother, and wife was a totally different path. However, I carried many of the ideals and much of the consciousness of the Party into my new roles. But I’m telling you, when I first got in front of classes, even though I had done a lot of tutoring, I realized over and over again that I don’t know a damn thing. I had been so busy being an activist; I hadn’t read enough. I didn’t do enough studying. That began a lifelong self-learning process in which I determined to learn about history, not just of racism and civil rights, but of the world. When I was active in the movement, I was a doer. I wasn’t like the Allwood character who read 300 books a year. When I became a teacher, learning and reading became my focus, so I could pass on ideas about history and the world through my classes and my writing.

A wooden “clenched fist,” circa 1965, appears in the exhibition, “All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50.” (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California)

(To learn more, pick up a copy of Judy Juanita‘s novel, “Virgin Soul.” And don’t miss her latest book of personal essays, “De Facto Feminism: Essays Straight Outta Oakland.” For information on the Oakland Museum of California’s exhibition, visit its page on “All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50,” which runs through February 12, 2017. To see more images of Black Panther women working behind the scenes, visit Billy X Jenning’s It’s About Time Black Panther Party archive.)

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

Trailing Angela Davis, from FBI Flyers to 'Radical Chic' Art

Trailing Angela Davis, from FBI Flyers to 'Radical Chic' Art The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights Anita Pointer: Civil-Rights Activist, Pop Star, and Serious Collector of Black Memorabilia

Anita Pointer: Civil-Rights Activist, Pop Star, and Serious Collector of Black Memorabilia Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and …

Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and … Protest MovementsThe American Revolution began as an act of protest, so it follows that the …

Protest MovementsThe American Revolution began as an act of protest, so it follows that the … Civil RightsAntiques malls and flea markets are full of shameful reminders of America's…

Civil RightsAntiques malls and flea markets are full of shameful reminders of America's… Politics and Public ServiceHistory is often told through the grand detritus of the political sphere—th…

Politics and Public ServiceHistory is often told through the grand detritus of the political sphere—th… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

A very enjoyable read, it’s great to hear the story of a woman in the Panther Party. Thanks for this interview, I’d like to see more like this

What an excellent article on a subject that rarely sees the light of day. Judy is an amazing talent, thanks for the interview!

Thank YOU, for opening Both Our Eyes. That’s OUR Good History, equally as important as learning about Slavery. Now that’s good teaching.

PEACE IN…

Thank you for this very necessary education on a special time for African American growth in our history.

If all African Americans are taught this history from early ages, it would instill a common mindset about our need for cooperation and unity in addressing our current sad state of affairs.

QUESTION:

What is the origin of color conscious racism, when did it begin, how, where, and by whom did it get its invention, and must truth of this knowledge be institutionalized to be taught in education curriculum at all levels of teaching and study???

African Americans, and the general European community, have had much trouble due to simply not knowing the origin of this problem that has plagued human life and peace for far, far, far too long.

Uprooting the problem begins at its beginning, and all must know it so that we can bury it as the deceptive , divisive, and evil it has been for all these centuries.

PEACE IN…PEACE OUT…

Judy, This is an invaluable and amazing piece of work. Bravo!