Whether you’re into comic books, antique jewelry, or vintage motorcycles, it typically takes a lifetime to build an admirable collection, years spent scouring flea markets, garage sales, and auction houses for each new addition. But for Joseph Makkos, a writer with a passion for antiquated printing techniques, his prized collection appeared all at once—in the form of a Craigslist ad offering thousands of historic New Orleans newspapers. For free.

“It’s like looking at a photocopy of Picasso’s Guernica versus the original painting.”

When Makkos first inquired about the collection in 2013, he found a room filled floor to ceiling with boxes, each stuffed with newspapers in protective tubing. “I walked down one row of boxes, counted horizontally and vertically, and did the math,” says Makkos. “Each row had at least a thousand boxes, so it was around about 30,000 newspaper tubes.” The earliest papers dated back to the 1880s, and the full collection included issues of “The Daily Picayune,” “The Times-Democrat,” and “The Times-Picayune,” which was created when the previous two papers merged in 1914. As a whole, the collection offers an amazingly detailed view of the city’s storied past—its politics, food, sporting events, local businesses, architecture, tragedies, and celebrations.

Makkos had actually noticed a listing for the lot a few months prior, when the papers were being sold for $10 each, but because of minimal interest and an urgent need to clear the building they were stored in, the entire archive was now free. Free, at least, if the mysteriously unidentified seller could find a suitable new owner who would ensure the newspapers would be well taken care of. Makkos accepted the challenge and had his 30,000 newspapers out by the following Sunday.

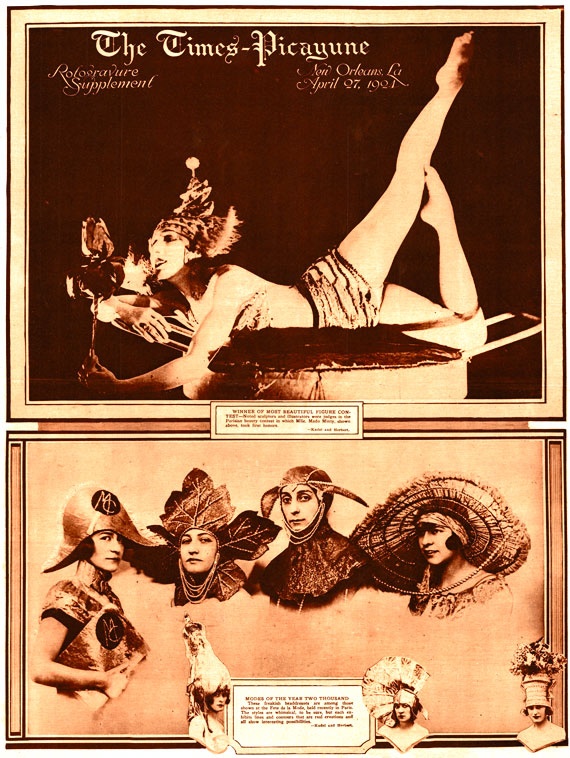

Top: A rotogravure supplement featuring futuristic fashions “of the Year Two Thousand,” from 1924. Above: Joseph Makkos sits among thousands of newspaper tubes in his New Orleans studio. Photo by Zack Smith.

In many ways, Makkos is the perfect caretaker for this gigantic archive. Raised in antiques stores, Makkos developed an appreciation for dusty relics through his father who dealt in historic lights and lamps in Cleveland, Ohio. Years later, while working on the publishing requirements for his Masters of Fine Arts in creative writing, Makkos got hooked on high-quality printing and bookmaking. “I really loved the craftsmanship of the books that were produced during the mimeograph revolution in the ‘60s and even earlier, the chapbook style of making books with French folds and letterpress covers,” says Makkos. “I really just fell in love with the printed word on the page.”

Makkos realized that the most distinctive printmaking processes, such as foil-stamping, die-cutting, and embossing, are today mostly limited to mass-produced industrial jobs, as huge corporations are more likely to front the extra cost. He began experimenting with some of these unique methods for various small-scale writing projects, while also keeping an eye out for older print shops that were liquidating their machinery, which he used to start his own collection of binding machines, presses, type trays, and lettering.

In 2006, Makkos stumbled across a defunct print shop called AF Laborde & Son Printers on Frenchman Street, in the heart of the New Orleans’ jazz scene. Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the business had shuttered and never reopened. “They were the most popular printers in the city from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries,” he explains. “The shop was relatively intact, including a darkroom, an art director’s office, linotype machines, a composing table, a lead smelter, a paper cutter, and all sorts of print blocks and letterpress type.” After years of attempting to contact the owner, Makkos was eventually reached by the youngest Laborde son, who asked for his help cleaning out the shop. In return, Makkos got to take his pick from an amazing collection of printing equipment.

Scenes of Makkos’ workspace: Left, a proofing press made by R. Hoe in the late 1870s or early 1880s; right, drawers of type and a handprinted poster. Photos by Ashley Pastore.

About a year later, Makkos came across the surprising Craigslist post, and was entrusted with this gigantic New Orleans newspaper collection. The archive has inadvertently introduced Makkos to certain outdated technologies, while also providing new subject matter for materials printed with his antique equipment. Now Makkos is working on several projects to give these newspapers new life, beginning with The New Orleans Digital Newspaper Archive, and encompassing local-history exhibitions, architectural-preservation work, and wearable merchandise. He’s also informally renamed the collection after Eliza Jane Nicholson, the innovative businesswoman who took ownership of “The Daily Picayune” in 1876 and helped it thrive.

But where did this extraordinary collection originate? Makkos traced his papers back to the British Library in London. “I can tell these were in bound library editions because they were stamped by the British Library, and occasionally I’ll find little pieces of string that were attached to the paper as part of the binding process,” he explains. “I think the papers were tubed in preparation for a retail location in New Orleans where they were going to be selling historic newspapers. Because they had been selling them off little by little, the collection’s not entirely complete, but I would guess it’s probably 90 to 95 percent intact.”

Apparently, the archive of New Orleans newspapers was bought by a dealer in Pennsylvania named Timothy Hughes, who purchased several shipping containers full of bound newspapers at auction from the British Library. After exchanging hands a few times, it landed in Makkos’ lap, and despite the collection’s excellent condition, all sense of organization had been lost. “When I open up a box, it’s like Christmas,” he says. “I’ll pull up one paper and it might be a Wednesday paper from 1899. Then I pull out another, and it’s a Sunday society section with a photo on it from the 1920s.” Thus far, the oldest newspaper Makkos has discovered is from 1885.

This 1913 feature section on “beauty spots” around New Orleans’ City Park shows how illustration and photography were combined in period newspapers.

Nicholson Baker’s book Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper describes these massive library auctions in the late 1990s, and it led Makkos to much of his information about his collection. Makkos explains that many libraries deaccessioned their newspapers in an effort to create more space. Archivists also worried about the deterioration of paper sources, believing that transferring documents to microfilm would help them last longer. “Each generation of archivists and librarians has a new take on the best methods for preserving their materials,” says Makkos. The U.S. Library of Congress started microfilming books and manuscripts belonging to the British Library beginning in the late 1920s, and the American Library Association officially endorsed the technique in 1936. But the technology didn’t spread nationwide until after World War II, when microfilm labs like Bell & Howell began sending representatives to pitch their products to librarians everywhere.

Suddenly, a heavy, bound edition of newspapers could be shrunk down to a single roll of microfilm. “I think that was really appealing to libraries,” says Makkos. Yet because of this process, millions of original newspapers, magazines, and books have been discarded or sold off, and with them went the palpable beauty of the printed form. “When was the last time you sat in front of a microfilm machine?” Makkos asks. “If you’re looking at a fashion section from 1914, originally done in four-color chromolithography, the microfilm version doesn’t even compare. It’s like looking at a photocopy of Picasso’s Guernica versus the original painting.”

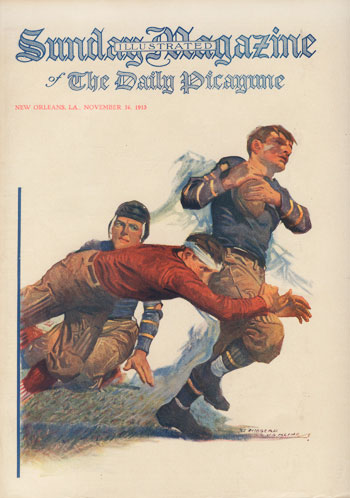

Makkos’ New Orleans collection is particularly remarkable because it documents the publishing industry during a time of great change, visible in the adoption of new technologies for printing illustrations and photographs, as well as the expansion of coverage to include new sections like literature, comics, ladies’ fashion, health columns, a letter-writing club, children’s games, and a pull-out magazine. The archive spans a time period known today as the “Golden Age of Illustration,” lasting from the 1880s through the early 1920s. “Although cities like New York, San Francisco, and Chicago started bringing photography into the paper earlier, it wasn’t used in New Orleans’ papers until 1900,” says Makkos. New Orleans’ papers were also behind when it came to incorporating color, which began around 1913.

“I think my favorite period starts just after the turn of the century, around 1901, when there was a major collision between illustration and photography,” he adds. “I have a bunch of papers set aside from this particular era, from 1901 up to 1914, just before the end of ‘The Daily Picayune.’ Everything about them was illustrated—there were these fabulous headlines and borders and circular photos. I can think of one image that shows these three little kids sitting by the fireplace on Christmas Eve. The illustrators of the ‘Picayune’ must have thought they were really smart because they drew in a ‘Times-Picayune’ newspaper. It shows this intentional manipulation of the content in a way that’s really interesting, like the birth of combining photography and illustration the way modern designers use Photoshop.”

Makkos has also come across a variety of near-forgotten technologies, like the gorgeous rotogravure photographs of the 1920s. “I just acquired an advertisement for rotogravures from 1924 in the ‘Saturday Evening Post,’ and it explains the entire process,” says Makkos. “The rotogravure was actually an etched metal plate formed into a cylinder, so when the paper was sliding through the presses, the plate itself was the drum. This process created these super-clear photo images, way finer than a typical photo printed on newsprint. They even used different paper, and when you hold the gravures up to the light at the right angle, you can see this silvery shimmer. It has a satin finish to it, resembling silver gelatin prints.” Even in digital scans of the rotogravures, he says, the level of photographic detail is mesmerizing.

Beyond its stunning visual components, the collection owes its unique flavor to a groundbreaking female publisher, Eliza Jane Nicholson, after whom Makkos has named the digital archive. “Eliza Jane was this brilliant young woman who came to New Orleans to visit a relative in the 1870s and ended up rubbing elbows with local literary types,” says Makkos. Born Eliza Jane Poitevent, she was also poet who wrote under the name of Pearl Rivers. While still in her early 20s, “Daily Picayune” owner Alva Holbrook made her the paper’s literary editor. “But it was this big insult to her family,” Makkos says. “It’s not something that a lady would do in the 1870s—move to New Orleans and get a job as a newspaper editor.”

As the story goes, Holbrook ended up divorcing his wife and marrying Eliza Jane a few years later. “Holbrook was her elder by 40 years, and he died a few years after they were married, but he left her the newspaper,” says Makkos. “There was a long litigation battle over its ownership, but she fought and won.” In 1876, Eliza Jane officially became the new owner of “The Daily Picayune,” although the business was $80,000 in debt, a colossal amount of money at the time.

Eliza Jane quickly took George Nicholson, the paper’s manager, on as a partner. “They ended up getting married out of necessity,” explains Makkos, “but I think they had a very happy marriage, actually. From what I understand, they were partners-in-crime, so to speak. She was the outspoken editor, and he was the clever business manager, and they were able to piece it together.”

During the 1880s, Eliza Jane had the foresight to transform “The Daily Picayune” from a dry paper for white-collar men to one with coverage appealing to a variety of readers, and women in particular. “You can imagine the New Orleans businessman just sitting on his lunch break, puffing on a cigar in a cafe in the French Quarter or in his office, reading the price of cotton or bananas or whatever, reading about the markets and these international news stories,” says Makkos.

“But Eliza Jane was able to make some sweeping changes by the time the decade was out. She started writing a column called the ‘Society Bee,’ focused on the high-society people in New Orleans. At first, the New Orleans elite were taken aback and didn’t want their lives being recorded. But in a short amount of time, she proved she was doing it with style, and they became these local celebrities because they were being written about in the newspaper. ‘So-and-so was in town from Savannah to visit so-and-so on such-and-such street.’”

Another important feature Eliza Jane introduced was the “Ask Dorothy Dix” section, which became one of the most widely syndicated advice columns in history. “By the late 1880s, Eliza Jane was able to hire and employ women, paying them the same rate she was paying men for writing articles,” Makkos adds. “So she was this proto-women’s rights character, but she wasn’t this flag-waving suffragist. She never subscribed to that sense of politics.

“Eliza Jane and her husband died a week apart in 1896, and by that point, the paper was drastically different. There was all sorts of literature, poetry, illustrations, and great features about topics around the world, I think partly because New Orleans was more European, South American, and Caribbean-centric. In the 1890s, the ‘Picayune’ was widely distributed to South America and the Caribbean. It had become a very interesting newspaper with tons of strange stories—this hybrid of the tabloid and scientific news models.”

This 1896 story on female bullfighters in Barcelona, Spain, inspired Makkos to write an article on bullfighting in New Orleans.

While the paper’s editorial staff was forward-thinking in many senses, its coverage of racial tensions in the mixed community of New Orleans was far from progressive. “The race coverage is very dark,” says Makkos. “For example, at the beginning of the jazz era, the music was really looked down on, like the hip-hop of its time. It was treated as a scourge on the city in ‘Picayune’ articles. The newspaper definitely wasn’t advocating for black-owned businesses or educating African Americans at the time. It was actually quite critical of allowing African Americans to vote.”

Amid piles of antique newspapers in his studio, Makkos’ voice brightens when he speaks about the potential of this amazingly preserved archive. “The stuff in this collection is not just republishable, it’s exhibitable,” he emphasizes. The next step is to start a process of selective digitization, because currently, the public can only access these newspapers through poorly photographed, low-resolution, high-contrast, reverse-scanned PDF files from microfilm. “There are tons of interesting graphics that could be pulled out and used for anything from postcards to T-shirts. But I also think that there’s another end to it, because there’s so much content here that can take us back to another time none of us have lived through.”

One potential application relates to the city’s historic architecture, which is perfect for Makkos since he’s recently begun a Masters of Preservation Studies at the Tulane School of Architecture. “There’s currently a big movement in New Orleans to restore all of these historic theaters. In one square mile, there’s already the Civic, the Joy, and the Saenger, and now they’re bringing back three more theaters. I’ve been reaching out to some of these groups because I have all this newspaper coverage from when these theaters were in their original peak form. For me, as a preservationist, archivist, and printmaker, it’s a pretty clear fit.”

Makkos’ collection includes ample coverage of historic New Orleans architecture, like this 1923 view down Carondelet Street.

From the balconied architecture of the French Quarter to the plantation-style mansions of the Garden District to the industrial blocks of the Bywater neighborhood, the physical fabric of New Orleans owes much to its unique history. And as Makkos has discovered, details of the city’s architectural heritage are well-documented in the pages of its historic newspapers.

“I’ve pulled out over a hundred papers related to New Orleans architecture, so I’m able to look at this comprehensive overview from 1902 through 1929. Reading these headlines and seeing the changes over the years is amazing. A couple of groups focused on architecture here in New Orleans have taken a particular interest in these source texts to feed a project called the Preservation Timeline that tells the history of local preservation from the 1890s through the modern era.”

In New Orleans, history and the present often overlap in strange and beautiful ways. Visitors praise the city’s “European” vibe, though its allure really derives from a blend of influences not found anywhere else—a Creole culture formed from the influence of African American, French, Spanish, and Native American ancestry. Using his collection of newspapers, Makkos is in the process of unearthing details of that heritage that even locals haven’t seen before.

Even after scouring archives across the city, Makkos hasn’t found any as complete as his, particularly when it comes to the illustrated supplements most libraries failed to save. “There’s an embarrassment of riches in this collection, so much good content that I can pick up any issue and find something fascinating,” says Makkos, “For example, ‘Oldest U.S. soldier to wed—surviving member of the Civil War.’ He was a young soldier in 1860s and now he’s in his 70s or 80s and getting married. I just found an illustration from the 1890s of a fire, and it reads, ‘Details of the horror—five bodies removed from the ruins of the building demolished by the gun powder explosion,’ and instead of a photograph there’s this incredible illustration of a building in total wreckage. A few months ago, I wrote a story on bullfighting in New Orleans for a local paper, inspired by an article from 1896 about female bullfighters in Barcelona, an extremely taboo topic for the time.”

Though the collection came to Makkos all at once, poring over the content of these papers will likely take years of effort, reading articles and scanning the individual pages. But in an era when newspapers and magazines are halting their presses and becoming online-only publications, the effort won’t be for nothing. Like decaying historic architecture, the marvelous details of these yellowed papers might be lost without someone like Makkos to champion them. “I have a letter from one of the upper-level business executives at ‘The Times-Picayune’ from 1892, and it’s this really menial letter about ordering some sort of shaving cream,” says Makkos. “But the letterhead itself is just gorgeous.”

(Keep up to date with Makkos’ projects at his NOLA DNA website, support the archive’s future, or see more of Zack Smith’s photography of New Orleans.)

Artisanal Advertising: Reviving the Tradition of Hand-Painted Signs

Artisanal Advertising: Reviving the Tradition of Hand-Painted Signs

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums?

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums? Artisanal Advertising: Reviving the Tradition of Hand-Painted Signs

Artisanal Advertising: Reviving the Tradition of Hand-Painted Signs Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male Printing EquipmentMetal and wood type, the cabinets designed to hold these blocky letters and…

Printing EquipmentMetal and wood type, the cabinets designed to hold these blocky letters and… NewspapersAlmost everyone has an old newspaper cover or two tucked away somewhere - a…

NewspapersAlmost everyone has an old newspaper cover or two tucked away somewhere - a… Mardi GrasMardi Gras is technically "Fat Tuesday" or "Shrove Tuesday," or the last da…

Mardi GrasMardi Gras is technically "Fat Tuesday" or "Shrove Tuesday," or the last da… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Wow a beautiful collection !

I am a screen printer / artist in New Orleans

Good for you saving this history .

The future generations will sing your name! As a Preservationist and mass media academic, your find is stunning.

One caveat: if it was published in the newspaper, it was common to the public. It was socially acceptable for your children to read.

Just because past generations censored history, doesn’t mean the facts aren’t there. If it was in the paper, it was on the streets.

Thank you for saving this great collection of New Orleans history.

Your reward will come as you read the many articles and the various advertising.

Nice save.

Wow I love history an old pictures books this was so cool

Thank you for preserving this history. My grandmother was a surgical nurse at Touro, and a graduate of the nursing school there (1915). These are the sights and scenes she would have seen. Thank you for sharing these.