Mobile homes have a bad rap. The minute you utter the words, “trailer park,” many people will come back with stereotypes about “trailer trash,” or slovenly, ignorant, beer-swilling yokels who leave busted appliances and inoperable cars outside their mobile homes. The “trailer trash” caricature has been all over pop culture the past few decades—from Cousin Eddie in the “Vacation” movie series to Jeff Foxworthy’s redneck comedy to “The Trailer Park Boys” TV and movie series. And the animosity toward the poorest and least educated trailer-dwellers has recently taken on a political dimension, as it’s often incorrectly assumed that everyone who lives in a mobile home must have voted for Donald Trump.

“You can’t get away from the trailer-trash concept, because much of it is self-inflicted by the industry.”

Oddly, cramped living quarters are making a comeback, under the guise of artisanal “tiny houses”—many of which resemble a wheeled trailer dressed up like a log cabin. Sold as a more sustainable way of living, tiny houses are considered stylishly rustic and telegraph a sense of moralistic simplicity that’s popular with the educated elite. But in place like San Francisco, where the land is often more valuable than the buildings that sit on it, where the heck do you park a tiny house … in a trailer park?

While tiny houses have dodged the “trailer trash” stigma, many types of shelters get lumped into that stereotype: Camping or travel trailers are shelters meant to be pulled to campsites by an automobile. Recreational vehicles (RVs) have the living quarters built into the auto itself, and are mostly used for camping. Mobile homes, like travel trailers, are meant to be pulled to a location by a truck, but they often stay in one spot for decades. Today, mobile homes have morphed into wheelless “manufactured homes,” which are delivered to trailer parks via flatbed trucks. In time, mobile and manufactured homes have grown to be as large as regular “stick-built” homes, taking up two or three lanes on the highway, a size that would be downright extravagant to a disciple of tiny-house minimalism.

Top: “Life in a Trailer Park in Florida” involved flower beds and socializing, according to this 1950s Tichnor linen postcard. Above: A 1960s advertising postcard promotes a two-bedroom trailer in the “Mobile Home Section” of Orange Blossom Hills, Florida. (Images via eBay)

Mike Closen and John Brunkowski—who split their time between Maine and Florida—think the classist shaming of trailer-park living needs to end. Even though they’ve never lived in a mobile home full-time, the couple have been avid RV campers for the past three decades, and they’ve bought mobile homes for their parents. Their obsession with camping, RVs, and mobile homes has given them quite the collecting bug. They have accumulated more than 20,000 trailer-related postcards, as well as several thousand other objects, including RV, trailer, and mobile-home toys and models; advertising pinbacks; matchbook covers; cups; magazine ads and articles; books; clothing patches; and emblems from the coaches themselves. Together, they’ve published seven books on the topic, including one focused on Kampgrounds of America, one exclusively about Airstream collectibles, and their latest, Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash: The Illustrated Mobile Home Story, published by Schiffer, which is about their collection as a whole. Through their objects, you can see the trajectory of mobile-living from horse-drawn carriages to sleek (and still beloved) metallic Airstream trailers to mobile-home parks as a surprisingly posh alternative to 1950s suburbia, where you get the white-picket-fence dream at a discount and everyone in the neighborhood goes swimming and square dancing together. I spoke with Mike Closen over the phone and he told me the true mobile-home history that, so often, gets overshadowed by the stereotypes.

Collectors Weekly: When you talk about trailers, that encompasses both campers and mobile homes, right?

Closen: Yes, and you’re hitting on one of the issues that we’ve confronted with all seven of our book about RVs, campers, and mobile homes. There’s no bright line between a travel trailer and a mobile home. Some of the shortest trailers in the world, 10- to 15-foot-long trailers, are put in one spot and never leave it, and people manage somehow to reside in that. So it becomes a fixed-place home, even though it’s very short. On the other hand, there are some very long trailers that go on the road all the time.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s 1953 comedy, “The Long, Long Trailer” boosted mobile-home and travel-trailer sales in the 1950s.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz made that point in their famous 1953 movie “The Long, Long Trailer,” which inspired a lot of Americans to consider living in mobile homes. Although Lucy and Desi poked fun at the RV lifestyle in the movie, audiences were impressed with the magnificent, upscale trailer they drove across the country. It had a bathroom with an early, primitive trailer shower. The film was so popular that a couple of manufacturers hired Lucy and Desi to advertise their mobile homes. We have a copy of that movie in each of our homes, in Maine, in Florida, and in our RV. I’ll bet John and I have watched the movie at least 40 times over the years; we can quote lines from it.

Collectors Weekly: Do mobile homes always have wheels?

Closen: Yes, though that doesn’t distinguish what a mobile home is and isn’t anymore. Certainly, a mobile home—just as with a manufactured home—has to be moved down the highway to get it from the factory to its final location. Whether the wheels are left on or not, it’s still a mobile home. In a lot of states, wheels determined whether you had to have a license plate on the vehicle. It also affected whether the unit became part of the real estate versus whether it continued to be personal property sitting on top of the land.

Vagabond’s metal emblem for its mobile homes and travel trailer, circa 1940s-’50s, depicts a hobo with a bindle. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: I noticed you have a lot of trailer-trash gags in your book. Do you enjoy that kind of humor?

Closen: Well, it’s out there, and it can’t be avoided. For this book, we decided that each chapter would begin with items perpetuating the trailer-trash myth, like the Jeff Foxworthy book, Redneck Extreme Mobile Home Makeover. After we draw you in, we attempt, in our lighthearted way, to reverse that notion. But when collecting trailer memorabilia, you can’t get away from the trailer-trash concept, because much of it is self-inflicted by the industry. For example, in the early days of trailers, Vagabond produced upscale, high-quality travel trailers and small mobile homes—and yet the Vagabond emblem affixed to the sides of their trailers featured a hobo with a bindle over his shoulder. Some of their trailers were even equipped with lamps or salt-and-pepper shakers shaped like a hobo with a bindle. Other companies put out all sorts of advertising with bawdy images of scantily clad women, including promotional playing cards and other memorabilia. Some of the stereotypes can be attributed to the industry execs, who should’ve been more aware of what they were doing.

The trailer-trash myth took off after World War II, when soldiers coming back from the war were faced with a housing shortage. Much of the travel-trailer and mobile-home industry got its jumpstart at that time. Confronting the housing situation, a lot of returning servicemen chose to move into RVs and mobile homes, at least for the short-term. It’s unfortunate that our veterans were also then associated with this notion of being “trailer trash.” In the ’40s, people living in “regular” homes also looked upon those in RVs and mobile homes as “trailer trash” because they had to go to the outhouse or the campground wash facilities just to use the toilet. We have hundreds of postcards in our trailer-themed collection just about outhouses.

A linen comic postcard, circa 1940, shows a man rushing to an outhouse from his trailer. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: What were the predecessors to mobile-home living?

Closen: We’ve been looking at mobile-home culture for a long time, and we’ve traced the mobile lifestyle in the United States back to Native Americans. Historically, they haven’t been credited with contributing to the development of the RV and mobile-home industry. It was the settlers moving across the country in their covered wagons that are credited with having the first mobile homes—and that doesn’t surprise me. If we really want to be serious about history, we need to credit nomadic tribes for devising ways to move their homes behind their horses and carry their tepees. They were doing it long before the pioneers were moving across the country in their more luxurious Conestoga wagons.

In general, settled people tend to look down on “nomads.” But with the expansion of the country from east to west after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the settlers living in a horse-drawn trailer or wagon were seen as heroic, confronting their fears of the unknown, including their fears of the Native American tribes living in the West. In the United States, the pioneers put a positive spin on the notion of being a nomad.

This tourist postcard labeled “Montana Sheepwagon, Sheepherder’s Mobile Home” shows an early wagon with a house-sized door. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Once homesteaders established farms and ranches, they hired cowboys to rustle cattle on the open range and farmhands to till the soil on fields far from the main house. These workers relied on horse-drawn wagons when they were miles away from a town or the central farm, and those wagons served as cooking facilities and bunk houses.

In the 19th century, you had all sorts of outcasts wandering the country by train or horse-drawn wagons. Salesmen, as well as circus and carnival people and performing minstrels, traveled from city to city or area to area to earn their livelihoods. Reform Christians found wagons useful, too; they toured the country hosting big-tent revivals and converting new believers.

An undated postcard shows “gipsies,” or Romani nomads, outside their horse carriages. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: In Europe and some parts of America, the nomadic lifestyle is also associated with the Romani people (disparagingly referred to as “gypsies”) and their horse-drawn carriages.

Closen: Yes. That wandering-gypsy stereotype, along with that of the train-hopping hobo, was associated with mobile homes for decades. In our collection, we have a mocking late-1930s “New Yorker” cartoon depicting a couple in gypsy clothes attending a New York City car-and-trailer show. Yet, in the early years, a number of campgrounds and manufacturers used romanticized images of gypsies to help sell their RVs.

Collectors Weekly: In the book, you show the bathing machines that the modest turn-of-the-century Europeans used. Did they also influence trailer design?

Closen: The bathing machines were towable dressing rooms used by beach-goers for a very brief period of time. By including them in the book, John and I were simply pointing out some of the shelters in the long line that eventually led to upscale travel trailers and mobile homes. People could sit or relax in their dressing rooms. They could change in and out of their swimwear. They would leave their possessions in them, and then go outside and swim or sit at the beach. Covered-wagon living was just an extended form of that: You kept your clothes, food, and belongings in the wagon. But you cooked outside, and you didn’t eat inside the wagon unless the weather was inclement.

Bathing machines were popular for “L’Heure du Bain” (“The Hour of the Bath”) at the beach in Boulogne-sur-Mer in Northern France in the early 1900s. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: How did trailer camping evolve into a form of vacation in North America?

Closen: In the late 19th century, we started having campgrounds and campsites in the U.S. and Canada, and tent campers were often delivered to the site via train. The wealthiest people in Canada and England continued to go on extended tours of the countryside by rail up until the late 1930s and early ’40s. Instead of using a travel trailer or tent, they would hire an entire lavishly appointed train car, and they brought their servants to attend to them. Their train car would be towed along, and then placed on a railroad siding for a period of time so the tourists could see the sights. Then the car would be picked up by another train and towed to the next location for a sizable sum of money. It was, again, a sort of mobile home. At least temporarily, these rich folk were living out of a train car.

What car camping looked like in the 1920s.

When automobiles were first mass-produced in the United States around 1900, Americans who could afford vehicles began auto camping. You used your car as part of the camper. People would drive their car down the road, stop somewhere remote on the roadside, and then set up a tent-like contraption. Sometimes they attached a canvas sheet to the top of the car and then propped the other side up with poles. Sometimes they’d park two cars next to one another and stretch a canvas between the tops of the cars.

On the very earliest truck chassis, people would build shelters that had fold-out devices similar to today’s slide-outs that could be covered in tent canvas. By the 1920s, Americans were making their own trailers they could attach to the back of their cars and tow. These early trailers tended to be very short because you didn’t have a very powerful vehicle to pull it. They were rickety contraptions, built of every conceivable material, mostly wood and the sort of canvas that would have been used on a covered wagon.

This 1922 mobile home was hand-built on a truck chassis. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Where did the campers go?

Closen: They’d show up in established parks or pull over to the side of the road and camp on empty-seeming farmland, although certainly they were trespassing on private property. By the 1920s, a lot of municipalities figured out that all these people traveling along the roadways needed a place to go. Several thousand parks or camps sprang up along the highways of America. Those would’ve had primitive outhouse facilities, but not much more than that. With each passing year and decade, those facilities expanded and improved. Almost immediately, as building trailers to camp and reside in caught on, there was an instant parallel growth and development of places for them to go. They were called tourist parks, trailer parks, tourist camps, and fish camps—which, by the way, didn’t help. That was more of the trailer-trash stereotype: “Oh, there’s a fish camp down the road where you can stay.”

This unused tourist postcard, circa 1930-’40s, shows a couple at a so-called “fish camp.” While fishing and boating were popular vacation activities, trailer parks on the water often had low-quality facilities, garnering them a bad rap. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Besides camping, what were early trailers used for?

Closen: Earlier trailers also served commercial purposes. We have a photo of a tiny trailer a barber used to travel to little towns and give haircuts in his trailer. I recently found a great old photo of a traveling post office from 1920s Great Britain. The postmen hooked a wagon to a vehicle and drove it to isolated rural areas that otherwise wouldn’t have mail service. One worker sat in the wagon and did the sorting while the other drove.

Collectors Weekly: What were the first manufactured trailers like?

Closen: In the beginning, of course, no factories made these travel trailers. You had to make your own. The next step was that people who first made trailers started selling the instructions to other people who wanted to build their own. Then early entrepreneurs started what they called factories, but they were really workshops that had more than one person building these trailers. Eventually, trailer manufacturers adopted Henry Ford’s assembly line.

The first factory-made travel trailers, the forerunners of the Airstream and the other metal coaches, came along in the early 1930s, using the same material airplane fuselages made of at the time. They had to be built of lightweight metal like aluminum to be towed down the road. Airstream got its start in the 1930s and took off. Today, Airstream is the longest-operating manufacturer of travel trailers in the United States, thanks to their unique design and roadworthiness.

A 1960s Mickey Mouse Club puzzle portrays Mickey and friends vacationing with a “canned ham” style travel trailer. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: That’s when you got what they called the “canned ham”?

Closen: Actually, the canned ham was a fairly early design, even before factory-made trailers. Americans made their own trailers in the shape of a canned ham because it was somewhat aerodynamic, but more importantly, the highest point in the trailer was in the center, where people would stand and need the headroom. At both the front and the back of the trailer, you see a curvature so that there’s less headroom, but that’s where the bed, table, chairs, or storage would be. Certainly, you are absolutely correct that the canned-ham look was a very popular metal factory-made design, as well.

Here’s an interesting footnote: In 1930s Great Britain, the boxy trolley design was more popular than the canned ham. Down the center of the trailer, it had a raised area like a trolley car has because that’s where you needed the headroom. On the sides, there would be beds, cabinets, seating, and so on.

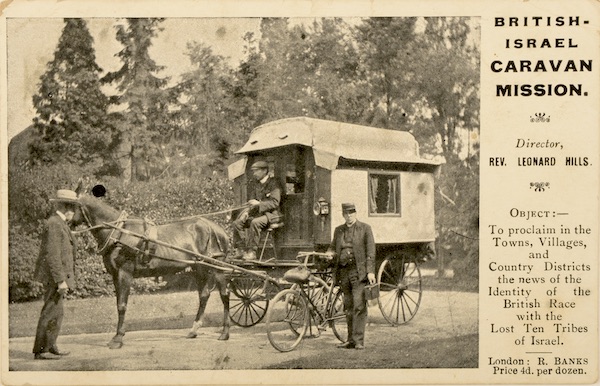

The horse carriage in this missionary postcard, sent in 1904, features the trolley design that was adopted for early British trailers. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Let’s talk about the aftermath of World War II. Before the war, most servicemen had been living with their parents, correct?

Closen: Yes, because of the age of the people who were drafted into the military. My dad was among them. He was at home at that point in life, and then the war came along and interrupted college—even high school for a lot of those folks—because they were on the cusp of adulthood. The U.S. military was mostly made up of young men at that time. When they came back, they were full-fledged adults, ready to move away from living with the family. I know that after I first left home to go off to college, after I had my first taste of freedom, there was no way I was going to live under my parent’s roof again.

Collectors Weekly: After the war, why didn’t the soldiers live in apartments in the cities?

Closen: At that time in history, the larger cities were not structured in such a way where there was enough land or apartment buildings for the returning soldiers. It was before the era of the high-rise condominium, and the towns had been built up at the point so that every inch was occupied by structures. I think the overcrowding at the end of the war was one of the principal reasons for the movement to the suburbs as well as campgrounds and mobile-home parks.

This trailer ad in the March 9, 1946, edition of “Saturday Evening Post” refers to the post-World War II housing shortage. You can see the living quarters in the cutaways has no bathroom. Click on the image to see a larger version. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Were mobile homes cheaper than cottage houses?

Closen: Oh, yes. From the beginning of trailer manufacturing, makers were savvy enough to build mobile home in various lengths, so that the length affected the cost. You have to remember that in the mid-’40s, the technology wasn’t there to put bathroom facilities in trailers. Even after the technology was developed in the late ’40s, there were still almost no trailers with bathrooms. Vagabond was one of the earliest companies to put a tiny, little toilet in the corner of one of its models. It was in the bedroom, and they had a dresser built over the top of it with a swinging door below. You could swing the door out to find a tiny toilet bowl. That was the extent of the bathroom—no basin, no shower, no nothing.

Collectors Weekly: Did returning soldiers view mobile homes as permanent or temporary dwellings?

Closen: I think most veterans viewed them as temporary housing until they got their feet on the ground and could move on. For one thing, the trailers were not as well-built as they are today, and they wouldn’t have been roadworthy for a long time. (The exception to the rule, of course, were the Airstream trailers. Something like 70 to 75 percent or so of all Airstreams ever made are still roadworthy.) Many millions of people came back from the war before many of the suburban stick-built residences were created. Some of them became permanent residents of trailers.

Collectors Weekly: It almost sounds like those trailer parks were an extension of being in a bunker or on the ship.

Closen: Oh, yeah! On the ship, the men would be living in dormitories with multiple bunks, so at least the trailers were private. A lot of those soldiers came back, got married, and had kids—the Baby Boomers were the product of that. A lot of folks would’ve been created in trailers.

This 1950s Mobile Homes Manufacturers Association ad from “Life” magazine boasts about the “modern” bathroom innovations featured in the latest trailers. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: When did trailers get bathrooms and how did that plumbing work?

Closen: In the early ’50s, the technology for trailer bathrooms developed to the point most manufacturers could include them in mobile homes and RVs, and that’s when the interest in both of those kinds of coaches exploded. Before then, outhouses in campgrounds and mobile-home parks served the people who lived there.

“For people who are social animals, the mobile-home park is a great place to live.”

Mid-century bathroom technology truly was the thing that allowed RVing and mobile homes to flourish. Almost immediately, the campgrounds and mobile-home parks came up to speed by providing the water and sewer utilities that they could hook into. When all of that came together, two multi-billion-dollar industries were born.

With travel trailers, you’d pull into a campground, hook up a hose to a water spigot, another hose to the sewer, and plug in for your electricity. When you’re ready to leave, you’d just unhook everything, go to the next campground, and repeat the process. In a mobile-home park, your mobile-home is effectively the equivalent of a stick-built house, hooked up to the local water, sewage, and electricity systems. In a campground, you pay a flat fee for sitting there, whereas with the mobile home, you get separate utility bills for each service.

A 1952 “Saturday Evening Post” article reads, “If you pity families who raise kids in house trailers—don’t. Their dwelling may have cost more than yours, it’s just as convenient, and a lot less trouble.” (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Did trailer parks become more fashionable and “suburban” in the early ’50s?

Closen: Yes, and they could be as good or better than suburbs. There were plenty of people who had stick-built homes that were not as nice, as modern, or as well-kept as many mobile homes. That’s why the trailer-trash myth needs to be debunked. It’s too quick a stereotype.

Collectors Weekly: How did the name of a mobile-home park determine its respectability?

Closen: There is a lot of significance in a name. If you call your park the Closen Fish Camp or Trailer Park, it’s going to have a different image than if you call it Northwest Villa, The Estate, Southern Resort, or The Marina. It’s just like curb appeal. Some of these places have been smart enough to call themselves some pretty fancy names, but they are still entry-level communities.

Around the United States, there have been a lot of upscale mobile-home communities. They are gated, pristine, and well maintained. The units in them are high-end mobile-home residences populated with people of wealth and education. Some even have golf courses, fine dining, bars, and swimming pools, like country-club living.

This 1950s advertising postcard for Blue Skies Trailer Village near Palm Springs, California, brags, “It is the concept of Bing Crosby, President. Co-habitues (and landlords) include Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Jack Benny, Barbara Stanwyck, Danny Kaye, Greer Garson, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Jose Ferrer and Rosemary Clooney, Claudette Colbert, and many others.” (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Bing Crosby had his own trailer park?

Closen: In the mid-century, numerous celebrities, from Lawrence Welk to Bing Crosby, had trailer residences. I’ve always thought it stemmed from the fact that when those actors and actresses were on a film site, they used mobile trailer units for their dressing rooms. They had probably become accustomed to their trailer, and then saw a mobile home as perhaps an attractive way to live.

But, in a number of those situations, to be fully honest, those people were investors in premier trailer parks and were undoubtedly being rewarded for their advertising endorsements. Certainly, it was helpful to the owners and developers of mobile-home communities to be able to say, “Oh, Lawrence Welk lives here” or “Bing Crosby lives here.”

This advertising postcard for Geer Mobile Homes in Grand Island, Nebraska, circa 1950s-’60s, shows a Mid-Century Modern style kitchen with the latest appliances. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me a little bit about how Mid-Century Modern style influenced mobile-home design?

Closen: The Mid-Century Modern look was mostly seen in the interior design, with the colors, furnishings, and wall coverings. Mobile homes need to be boxy, unlike canned ham or Airstream travel trailers. You want the full headspace, so the exterior of mobile-homes was never really influenced by design trends. But the interiors changed with every fad, like the shag carpeting that you and I lived through at one awful, awful time. They can be remodeled as often the stick-built house so people can make their interiors current and fashionable anytime they like.

Collectors Weekly: In the 1950s, when pin-ups were often used for advertising, did this create an association with promiscuous women living in mobile homes?

Closen: Oh, yeah, and that’s largely a fiction. Issues of infidelity can be present anywhere, under any circumstances. Again, part of the stereotype is that low-life, low-quality people live in mobile-home parks.

This 1946 comic linen postcard by Curt Teich Co. of Chicago depicts trailer dwellers as country bumpkins and the social aspect of trailer parks as a threat to marriage. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: It seems like mobile-home parks had a social aspect that suburban subdivisions lacked.

Closen: For sure. At an RV park, you might have a picnic table and a grill where you can cook out and eat. However, from the earliest days of the mobile-home parks, the notion was that this trailer was going to be your home. You had a bit more space around you, so you could have a white picket fence, a flower bed, and a dog or cat. But since the whole park is a sovereign entity of sorts, there’s a boundary around it, and the people within it are then part of a community. Virtually every park had a community center or a clubhouse, where they held meetings, shared weekly coffee hours, played bingo or shuffleboard, square danced, and hosted potlucks. I think mobile-home living has been far more successful at community-building than life in a high-rise.

As a young professional in a big city, I lived in a number of high-rise buildings, and I didn’t even know my neighbors next door. In some respects, the much maligned mobile-home parks have even better lifestyle opportunities than other housing. We housed my mother and father in a manufactured house here in Florida, which was placed in a mobile-home park with more than 800 coaches. They have a huge clubhouse with a ballroom, a swimming pool, shuffleboard, tennis, and a club for almost every hobby in the world. Some people who consider themselves loners are more happy when they have privacy. But for people who are social animals, the mobile-home park is a great place to live.

A resident of the Homecrest Mobile Home Park would have worn this patch on his or her jacket around the 1950s-’60s. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: In the book, you show mobile-home park membership patches. Would people put them on their clothes and wear them with pride?

Closen: Oh, yes, for sure. In mobile-home and RVing communities, people sewed fabric patches onto their jackets indicating their allegiance to their mobile-home park or their trailer or RV manufacturer, like Winnebago, Airstream Club, or New Moon. Winnebago, for example, has the Winnebago International Travelers, or WIT, which holds regional and national conventions. You would wear the emblem on your jacket or fly a flag from your RV.

Collectors Weekly: How was ham radio connected to trailers?

Closen: Around the world, most amateur radio, or ham radio, operators broadcast from their homes. But people with travel trailers or RVs realized that moving around increased the range of their opportunities to communicate with other amateur radio operators. It was especially popular in the ’60s and ’70s. You’d be sitting there at your radio with your headset talking to somebody in Spain or Russia. People wanted to document this connection in writing, so they would keep log books. They would often send a postcard to the person they spoke to and ask that person to send them a card in return. It didn’t take long before people weren’t sending just plain white or beige postcards. They were putting images on the postcard, called a QSL card, and often it was an image of their RV, trailer, or mobile home.

This QSL card from the 1970s shows a ham-radio antenna on top of a “gypsy” wagon. (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: I’m from Oklahoma, and I always heard it was a bad idea to be in a trailer during a tornado.

Closen: Or a flood. Water and mobile homes don’t mix. If a stick-built house is in the path of floodwaters, the house might be damaged significantly, but usually it’ll still usually be there. A mobile home, like a car, is a contained unit, and if much water comes along, it’s going to sweep the mobile home away. During tornadoes and storms, mobile homes just are not as structurally sound as stick-built homes.

Collectors Weekly: It’s the downside of being poorer, right—you have to buy a cheaper house and then it’s more likely to fall down?

Closen: Yes, exactly. It almost seems like tornadoes target mobile-home parks. But in reality, what happens is that mobile-home parks simply suffer more damage from those storms. It is a fact of life, but the risky nature of mobile homes is also part of the trailer-trash concept.

Some collectors are drawn to mobile-home license plates, like this 1976 tag from Oklahoma, a state that’s famous for its tornado season. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: You mentioned in the book the stereotype of people keeping appliances and spare tires outside their trailers.

Closen: Again, that’s part of the Jeff Foxworthy view of mobile-home living, which we had to acknowledge and deal with. We’ve traveled the country and the world. We’ve been to plenty of areas of the country where there are vehicles on blocks, refrigerators and freezers, and all sorts of things in front of a mobile home. But golly, here in Florida and in Maine, there are stick-built homes where people are doing the same thing. We drive by countless stick-built homes, where if the garage door is open, you can see it’s stacked with boxes, and all sorts of random stuff, while the vehicles are all parked on the driveway outside. The truth is mobile homes are often smaller than stick-built houses and lack enclosed garages. When trailer dwellers run out of room, their things might end up in the front yard.

Douglass Crockwell painted “Trailer Camp Friendships” for a U.S. Brewers Foundation beer ad, which appeared in the April 1953 issue of “Woman’s Home Companion.” Drinking beer at the trailer park looks like elegant, upper-middle class fun. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: I guess it’s still acceptable to mock people for being poor or having bad taste.

Closen: Sadly, that’s one of those prejudices people tolerate too easily. It’s unfortunate. Some people are poor and just trying to survive. But plenty of people who are much better off are buying mobile homes, too. Even people who live in mobile homes out of economic necessity should not be burdened with the addition of that stereotype. They’re dealing with enough issues as it is.

Collectors Weekly: Is trailer memorabilia a pretty big collecting field, or are you two kind of it?

Closen: We have more of that genetic defect than most people, certainly. We collect over so many areas—we do postcards, advertising, books, and emblems—so we’ve really been bitten by the bug. But many people who do RVing or mobile-home living have a hobby that involves some sort of collecting, whether it’s the amateur radio cards or advertising from vintage magazines. There are plenty of collecting subcategories with regard to RVing and mobile homes. We just do it more broadly than most people.

The July 1960 issue of “Popular Mechanics” shows an idealized suburban family outside an elaborate mobile home. The cover story is entitled “Trailers Join the Country Club.” (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: It’s funny to think of people who are into compact living are also into collecting.

Closen: Some of it doesn’t take much room. Take postcards, for example. It’s sometimes called shoebox collecting because a 3×5 postcard is the perfect size to fit in a shoebox. You can take a standard shoebox and fit 500-1,000 postcards into it. A sizable collection of postcards can be done in a relatively small space. People tend to specialize. They collect postcards about a particular, narrow topic. Another example is matchbook covers; you can also store a lot of them in a small area.

Collectors Weekly: In the book, you also show vintage company placards or emblems that would be attached to the vehicles.

Closen: Those are tougher to get, of course, because those are permanently affixed to the coaches. But if you can find a salvage yard, you might come across a few. A lot of people have been savvy enough that if a coach has been damaged in a storm or an accident, before they let go it to the junkyard, they’ll pull off the emblems. Those things can be highly valuable. That is another field of collecting that may or may not take up a lot of space. Some of those things are large, but a lot of them are relatively small.

A vintage linen postcard of Willow Trailer Park in Long Beach promises clean palm-lined streets and a leisurely California lifestyle. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: Since you collect a broad range of objects, how do you hunt for your collectibles?

Closen: We use all the standard sources—antique stores and malls, flea markets, estate sales, and eBay. Yard sales and garage sales can sometimes have treasures about RVing and mobile homes. It’s hit and miss, but going on the hunt is part of the fun. If you go to a postcard show, the dealers have their cards alphabetized by subject—it’s absolutely remarkable. Some dealers laugh at me when I ask about RVs and mobile homes, but a lot of them have collected cards on those topics. We also go to toy stores and see if they have any modern models of RVs or mobile homes. There is a huge amount of Airstream toys and models on the market. We’ve got three or four display cases here in the house full of Airstream stuff.

This 1950s tin toy, made in Japan, features a fully detailed interior of a “house trailer.” (From Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Why do you think Airstream has become hip while mobile-home living is generally mocked?

Closen: The Airstream trailers were borne out of the stylish Art Deco Streamline Moderne movement. Today, no other trailer or mobile home is made like they are. Back in the ’40s and ’50s, a couple of other companies, like Spartan and Vagabond, were also building the aluminum silver-bullet airplane fuselage-looking trailers, but those companies didn’t survive. Airstream has survived, and they’re so well-made, roadworthy, and aerodynamic. When you shine them up, they’re remarkable. If you were to go to an RV dealer and look at the new ones, they are just magnificent inside—bright, clean, and well-designed. Even the 2017 model looks fantastic. The shortest, little, tiny Airstream is at least $60,000 or $70,000, while the medium and larger ones are well over a hundred thousand dollars for a trailer—often more expensive than buying a stick-built house. They’re so iconic and good-looking that the Museum of Modern Art in New York has an Airstream in its collection. We’ve written an entire book on Airstream, the only book out there on Airstream memorabilia.

Streamline was a brand of Modernist airplane-fuselage-style trailers that competed with Airstream. The line was featured in the October 1963 issue of “Trail-R-News.” (Via TomPatterson.com)

Collectors Weekly: Speaking of unconventional homes, in the book, you say houseboats are also a form of mobile homes.

Closen: We were trying to be a little cute. People have tried a lot of alternative living spaces. Years ago, Winnebago decided it was going to build a mobile home in a helicopter. You’d sit the copter down, and it had an awning you could pull out. Obviously, that was a gimmick. Yes, a houseboat can be sort of a mobile home, if it’s self-contained and has water, electric, sewage, and kitchen facilities. You see those around Seattle, San Francisco, and other waterfront communities. Today, HGTV has shows about water-living people, who build homes that sit in marinas. They can be quite expensive.

Collectors Weekly: What are the other comparable lifestyle trends today?

Closen: I’m a big fan of HGTV, and I’m seeing this tiny-house craze that’s going in San Francisco and other places. TV audiences are fascinated by all the people who are willing to try to live in 200 or 300 square feet. That was the size of my college dorm room, and when I think back on those years, I wonder, “How did I survive graduate school in that room?” In a way, we’re almost coming full circle here. A bunch of the tiny housers are living in less square footage than would’ve been available to servicemen post-World War II. Unlike the veterans, many of them have other options, but they’re choosing to live in a tiny house to embrace a simple, minimalist lifestyle. I think the tiny-house lifestyle is going to be tough for people with kids or people who want to have kids. There’s just not enough space for children in most of those homes.

The manager of Pine Shores Trailer Park in Sarasota, Florida, sent this shuffleboard postcard to entice a Maine citizen to winter there in 1949. He promised a new large bathhouse, modern laundry, improved electrical and water systems, an attractive recreation hall, and fishing. (Via eBay)

Collectors Weekly: Why don’t they just move into mobile-home parks?

Closen: While young people are embracing the tiny-house movement, for the most part, they don’t want to adopt the trailer-park lifestyle. In the past few decades, mobile-home parks tend to be occupied by people who are older or retired. Part of that is because a lot of these people have more than one home, of course. Mobile-home living is affordable enough that you can have a home in two or three places, including a warm location near a beach.

Collectors Weekly: It strikes me that mobile-home parks have a lot of potential as singles communities.

Closen: To my knowledge, there haven’t been any organized singles mobile-home park locations. But what happens is as people age, their husband or wife passes on. So you’ve got a lot of elderly but single retired people moving into mobile-home parks in Florida and the other warm-weather places. There, some elderly people will partner up because they don’t want to live alone at that stage, and I don’t blame them. It happens all the time.

(“Don’t Call Them Trailer Trash: The Illustrated Mobile Home Story” is one of several books on RVs, trailers, and mobile homes by Michael Closen and John Brunkowski. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

When Postcards Made Every Town Seem Glamorous, From Asbury Park to Zanesville

When Postcards Made Every Town Seem Glamorous, From Asbury Park to Zanesville

Before Camping Got Wimpy: Roughing It With the Victorians

Before Camping Got Wimpy: Roughing It With the Victorians When Postcards Made Every Town Seem Glamorous, From Asbury Park to Zanesville

When Postcards Made Every Town Seem Glamorous, From Asbury Park to Zanesville Don't Call Them Bums: The Unsung History of America's Hard-Working Hoboes

Don't Call Them Bums: The Unsung History of America's Hard-Working Hoboes PostcardsPostcards, sometimes spelled out in two words as "post cards," emerged duri…

PostcardsPostcards, sometimes spelled out in two words as "post cards," emerged duri… CarsThe phrase “classic cars” generally conjures a red Ford Mustang convertible…

CarsThe phrase “classic cars” generally conjures a red Ford Mustang convertible… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great read!

My wife and I lived in an owner occupied no subleasing allowed park for several years when we first married. MUCH better lifestyle than a noisy apartment complex.

I do have a small correction to this article, the amateur radio QSL card depicted is actually a citizen’s band CB radio card which is a completely different radio service.

Thanks again for the great article.

I have been a Facebook user for many years. At one point I noticed the explosion of “tiny home” entries and how new and exciting they were. I got so tired of seeing them I finally updated my status with this comment “Tiny homes are not new! They are called TRAILERS people and they’ve been around for decades!!”

Although this article was well written, researched, and thorough, it left out a critical component of the rise of trailer and mobile home living–the invention of air conditioning. Living in a small, metal dwelling, especially in Florida, wasn’t remotely feasible until air conditioning became affordable and widespread in the early 1950’s.

I want a traveling streamline to go west again. To be free to wonder and explore, to document the wonders of the vast wast, so pristine, so open, a fantastical journey, meeting fantastical wanderers. There are no people comparable. Born to roam, born artist.

I enjoyed watching the Tiny House shows, and in doing so, I was reminded why I would never want to ever live in one. There’s “tiny” and then there’s “teeny-weeny.” Many people who opted to sell their brick and mortar homes were in debt and were looking to downsize, and get out of debt. Kudos to them. I recently read that a large number of people who went tiny, did not like it and were trying to sell their little dream homes. I totally get it. I lived in a mobile home in a “trailer park” for about 15 years. The main reason I moved there was to get my son into a good school system, and the trailer park happened to be in a village of only 500 people which was incorporated into a great school system (which was just voted to be the BEST school system in the USA this year). The trailer park was owned and run by a lecherous middle aged man who kept everyone on their toes. One of the rules was that there were no children allowed (my son made it before the deadline). If you had children after you moved in, you had to sell and move by the time the child was 2 years old. They couldn’t get away with it now. Visitors had to register (Hey! this is a trailer park, not an exclusive gated community!) After about 7 years, the owner sold the park to a corporation. WELL, things started going downhill from there. They now allowed anyone move into the park. I know it’s not politically correct to call people “trailer park trash” so I will refer to them as the “riff-raff.” What was once a nice, well maintained community with long term residents, became a noisy (stereos, fighting, mufflers, you name it) trailer park that all the old timers moved out of. The people who replaced them were not the cream of the crop. NOT because they lived in a trailer park, but because of their loud, boisterious, thieving, drug taking, non employable way of life. Unfortunately, the “riff-raff” gives everyone who lives in a trailer park a bad name. Imagine my surprise when I went to one of my son’t football practices and was invited by a couple of mothers to join them on their blanket in the grass. They asked where I lived, and I copped out and only named the street I lived on. They pressed me further and I told them the mobile home park. WELL! If they would have had a can of Raid at their disposal, I would have been sprayed into oblivion. They turned their backs to me, and pretended I wasn’t even there. The snobs! LOL So, yes, many people living in mobile homes get a bad rap. No one should be called “trash” no matter where they live….unless it’s those women who thought they were too good to allow me in their presence. ?? I hope I didn’t offend anyone. Believe me, I totally understand. ? I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article. It was very well written.

Great article. Very detailed! I lived in a trailer park in the 80s in Miami. When we moved in it was still reminiscent of life in the 50s. Mostly families, elderly, and winter vacationers who returned every year for the warm weather. I have postcards showing what it looked like in 50s and 80s. But as the 90s arrived and more people moved in.. The park quickly began to decline. And crime became rampant. Eventually many moved out and the park was closed. I have photos showing how it remained abandoned for years. It is now the location of a Walmart. So sad. But I’m happy to see that many have begun restoring old vintage campers and are hitting the road with them. Hope to do that one day! Thanks for sharing.

Great Story! Needing a place to stay at for a few months at a time, I found a deal in a Mobile Home Park near the Gulf of Mexico. It was a 1963 ‘Tin Can’. So funny to read they were called ‘Canned Ham’. I told my friends in Kentucky that I had a ‘FL Cottage’ near the beach. After doing all the remodeling and seeing just what it was made of, I started calling it ‘My Florida Tin Can’. After one year, and the remodel complete I sold it and moved up in the park. Up as in two ways; up the hill and into a DoubleWide! Now I started singing the opening song to the TV show; The Jeffersons……Moving On UP!

For more info on mobile homes, check out Wheel Estate by Allan D. Wallis (Oxford University Press, 1991/Johns Hopkins Press-paperback edition, 1997).

I just purchased a 1956 Biltmore park model trailer. I believe it is 26 feet long. I would appreciate it, if someone could point me to some literature on this trailer.

Great article!