Today, travel by airplane can feel like a dreary slog. You have to get up too early and stand in long lines, subjected to other people’s screaming babies and rowdy children. The security line requires an awkward juggling act of bags, coats, laptops, and shoes. Then, you get squeezed into a cramped plane cabin, where you must breathe recycled air for hours on end, subsist on soda and pretzels for dinner, and have limited access to a bathroom for half the flight as the plane bumps through turbulent skies. You pray that when you finally land, your bags will show up.

Top: Southwest stewardesses in 1971. (Via Museum of Flight) Above: Cliff Muskiet on a KLM flight as a boy. (Via Uniform Freak)

It wasn’t always so. In the 1970s, the tail end of the “Golden Age” of civil aviation, young Cliff Muskiet looked forward to his family’s annual plane trip from their hometown of Amsterdam, Netherlands, to New York City and back. Air travel was expensive then, and the experience still lived up to its promise of modern glamour and luxury. When he was on the ground, Muskiet entertained himself drawing pictures of sleek jetliners and cutting images of airplanes out of travel magazines. From age 5 on, he knew he would become a flight attendant.

Muskiet realized this dream when he was 21, after spending his teenage years cleaning planes for KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, bringing home schedules, safety cards, menus, napkins, souvenir wings, and little salt-and-pepper shakers for his burgeoning aviation collection. Then, when he was 15 in 1980, his mother presented him with a gift that changed his life: A KLM uniform from the early ’70s, made from Trevira 2000 polyester in the airline’s signature blue, replete with a big, pointy disco collar.

“I was like, ‘Wow, this is fantastic!’” Muskiet says. “Because uniforms are hard to get, I was really proud of it. At the same time, I thought, ‘I want to have more.’ So I started writing letters to different airlines. As a result, I was invited to visit Martinair and Transavia, two Dutch charter airlines. In 1982, they changed uniforms, so they gave me their old sets. Then I had three uniforms.”

Hughes Airways flight attendants pose on a plane’s wing in 1971. (Via Museum of Flight)

It was 10 years before Muskiet came down with uniform fever again, when he had a long layover in Accra, Ghana, while working as a steward for KLM in 1992. He decided to drop by the Ghana Airways office and ask if they had any old uniforms. They did, and they were willing to sell them for just a few dollars.

“People tend to forget the reason why flying has become so bus-like: It’s because, well, it used to be more limo-like.”

“I thought, ‘If it’s so easy to get uniforms, I’m going to write more letters,’” Muskiet says. “I didn’t have a computer at the time; there was no Internet as we know it yet. So I had to write physical letters and send them in the mail. Then maybe once or twice a month, I would receive an answer. And maybe once or twice every other month, I would receive a little package with an old uniform. I got more and more, and now I have 1,275 uniforms.”

Muskiet generally approaches airline offices and not former flight attendants, because, he says, most stewardesses from Europe and other places around the world don’t own their uniforms, so when they resign or retire, they have to return it to the airline. When an airline gets a new stewardess look, they generally keep their old uniforms in storage, sometimes for years. In the United States, however, flight attendants often pay for their uniforms, and then they’re allowed to keep them when they’re done.

This KLM Royal Dutch Airlines uniform, worn 1971-1975, was given to 15-year-old Muskiet by a friend of his mother. (Via Uniform Freak)

“When I’m abroad, I always go to local airlines and ask them for a uniform,” he continues. “I introduce myself, I show them a huge portfolio with the different items in my collection, as well as articles about it from newspapers and magazines. Usually, they are very impressed and give me a uniform.”

Eventually, Muskiet starting photographing and putting his uniforms online. Thanks to his Uniform Freak website, Muskiet has become something of a celebrity in the aviation-collectibles world.

“A couple years ago, I was in the Philippines, so I went to a local airline office,” he says. “The lady working there recognized me. She said, ‘Oh, you’re the guy from the website.’ I said, “Well, if you know my collection, you’ll know why I’m here.’ She started laughing, and because she knew exactly who I am, I got a uniform. The website really opens doors.”

Todd Lappin’s airline ramp jacket collection filled up a closet in his San Francisco home. (Photo by Todd Lappin, via his telstar Flickr page.)

Unlike Muskiet, Todd Lappin, who describes himself as “sort of a recovering airline-collectibles junkie,” never worked for an airline. A former magazine editor for “Wired” and “Business 2.0” and a former product manager for Flipboard, Lappin has long been obsessed with all forms of transportation, both civilian and military, whether it be trains, buses, ships, or planes. Growing up, he thought jets were just the coolest.

“You had to be Miss Universe or Miss World. You lived this glamorous life because only a few people were able to fly, and flying was really something back then.”

“I was into planes when I was a kid, and as an adult, I started to think of them as amazing design objects,” he says. “I’ve been able to pursue my interest in planes in all sorts of crazy, weird ways, which has been great. I’ve done a lot of poking around the boneyards down in the desert where the planes go to die. It’s fascinating because that’s where you really see planes as anatomical structures. You see them literally with their guts spilled out. You kick a piece of dirt and a control panel pops out.”

Not only does he love to explore aircraft boneyards, but he’s also been known to wander around abandoned military bases. Lappin’s Modernist home in San Francisco is modeled after the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, with dials for light switches. A side of a 707, found in a boneyard, hangs on the living room wall, and a galley cart with airline glasses serves as a wet bar.

Lappin approached airline fashion from a whole other direction: The jackets worn by workers on the airport ramps seemed like practical items he could wear. “In earlyish days of eBay, I was in an airport, and I saw some guy working for United in this cool jacket,” Lappin says. “It appealed to me because it was an airline thing, but also at the time I was riding around the city a lot on a bike, so having a jacket with a bunch of reflective stuff painted onto it seemed like a good idea. For me, it was a twofer, something that was a bit weird as fashion, but also practical from the standpoint of being a pedestrian out at night.

Lappin holds up a United Airlines ramp jacket from the late 1960s-early 1970s, back when the airline was calling its 747s “Friend Ships.” (Photo by Lisa Hix)

“So I started looking for airline ramp jackets, mostly on eBay. As these things often go, it became an obsessive, little world, and I ended up geeking out really hard.” After Lappin got 50 ramp jackets or so, he decided to go cold turkey on his eBay hunting. “I laid off after I filled up a closet and had way more than I could ever possibly wear. I told myself, ‘If you keep going beyond this point, you know it’s a cry for help.’ And I felt like I had most of the cool airlines.”

“If you look at the Pucci uniforms, you can’t imagine that women wore them.”

Commercial airlines go back as far as 1909, with the first civilian-passenger flight in the United States taking place in 1914. According to AvStop.com, in the United States, the sons of wealthy magnates served as the earliest flight attendants, known as “couriers,” until the mid-1920s. As airlines attempted to save money at the end of the decade, the co-pilot often took on the role of tending to passengers, including serving them food and drinks.

In the United Kingdom, Imperial Airways employed “cabin boys” or “stewards” during the 1920s. In the U.S., Stout Airways had the first male stewards in 1926, while Western Airlines had stewards serve food starting in 1928. Because commercial air travel was so new, early airlines wanted stewards to wear uniforms that would instill confidence in the flight experience, so they wore military-inspired outfits with hats, epaulettes, insignia, and brass buttons on the jackets.

A United Air Lines flight attendant and nurse in the mid-1930s. (Via Museum of Flight)

United Airlines hired the first female steward, or stewardess, a registered nurse named Ellen Church in 1930. By 1936, airlines had shifted to hiring female registered nurses over men, since a large part of their job was to care for passengers who were nauseated and vomiting in the noisy and uncomfortable DC-3 planes. Often these stewardesses, or “air hostesses,” wore regular nurse uniforms, while the flight attendants for United also wore green berets and capes.

Unfortunately, the women were also subjected to male passengers groping and grabbing them while they served food, earning about $1 an hour. Stewardesses had to pledge they wouldn’t get married or have a baby while working for the airline; if they did, they could be fired. During World War II, registered nurses left their civilian jobs to join the war effort, so airlines hired young women without nursing skills to take their place.

On the album cover of 1958’s “Come Fly With Me,” Frank Sinatra beckons his listeners to join him on TWA’s C-69 Constellation.

These women had to be comely, as described in a 1936 “New York Times” article, “The girls who qualify for hostesses must be petite; weight 100 to 118 pounds; height 5 feet to 5 feet 4 inches; age 20 to 26 years. Add to that the rigid physical examination each must undergo four times every year, and you are assured of the bloom that goes with perfect health.” At the time, it was understood that these applicants should also be white.

After World War II, the advances in military technology such as cabin pressurization were applied to commercial airliners, and these new planes were faster, more comfortable, and carried more passengers. Jet airliners like the C-69 Constellation, the Boeing 707, and the Douglas DC-8 captured the public’s imagination, and in the 1960s, new airports were popping up all over the place. But in the mid-20th-century, air travel was expensive enough to be merely aspirational for most people, who were more likely to put their suitcases in the trunks of their cars and hit newly laid freeways.

These fliers sure look like they’re having fun in this early 1970s Braniff International Airways photo, featuring stewardess in Pucci uniforms. (Via TheFoxIsBlack.com)

“In the ’50s and ’60s, you really started to have what we would call ‘mass aviation’ where the planes got a lot safer and the experience of flying became a lot more common, but I wouldn’t call it democratic,” Lappin says. “Whenever I hear people complaining about airlines becoming buses and wondering what happened to the good, old days when they used to give us all this stuff, I say, if you go back and you look at how much a ticket cost back then, we would not be flying. A standard economy ticket to go cross-country, New York to San Francisco, would cost somewhere around 1,500 bucks in today’s dollars.”

Indeed, flying was thought of as a ritzy experience. “On the cover Frank Sinatra’s 1958 album ‘Come Fly With Me,’ there’s Frank beckoning, get on my plane, and it’s a TWA Constellation, which is a beautiful airplane,” Lappin says. “Of course, it was a more luxurious experience because it was a much more elite experience. So people tend to forget that and the reason why flying has become so bus-like. It’s because, well, it used to be more limo-like.”

In 1973, Braniff asked artist Alexander Calder to paint one of its Douglas DC-8s, which became known as “Flying Colors.” (Via SuperRadNow.wordpress.com)

In the 1960s and early 1970s, air travel meant futuristic glamour. Famous designers and artists like Raymond Loewy, Emilio Pucci, and Alexander Calder were recruited to construct a Modernist look for the airlines—from their logos and stewardess uniforms to the airport interiors and even the airplanes and fuel trucks on the ramp. People who were wealthy enough pay for a flight got to enjoy a posh experience in the air, and first-class passengers might have even enjoyed cozy onboard beds, luxurious meals, or live piano performances. And the passengers were waited on hand and foot by gorgeous female flight attendants, dolled up in smart, fashionable outfits.

“It’s not really a thing even within the subculture of the subculture of the subculture. It’s like you’re a geek among geeks.”

“In the late ’50s, Pan Am worked with Walter Landor Associates to do the famous globe that we all associate with the airline,” Lappin says. “Then in the ’70s, Braniff International Airways did the whole thing where they had Calder, an artist, painting their airplanes and designing their identity. That was some pretty radical stuff. If you look at the identity schemes or the brand documents from all of those mid-century airlines, they didn’t just think about the planes. They were thinking, ‘How does the uniform look, how does the truck look, and how does the fuel truck look when it’s sitting next to the airplane?’ For the first time, it was all seen as an integrated identity.”

Thanks to the bus-like nature of modern-day air flight, most aviation enthusiasts are enchanted with the ’60s and ’70s, when it was still a thrill to board a plane.

Delta Airlines flight attendants model their uniforms for the summer, at left, and winter, at right, in the early 1940s. (Via Museum of Flight)

“When I was a journalist, I was having a little fling with Transworld World Airlines and its 1960s identity, especially the Raymond Loewy logo with the classic twin globes that was awesome looking, and its neofuturistic terminal designed by Eero Saarinen. I did an article for the ‘New York Times’ about this guy named Dan McIntyre, who basically had his entire basement set up as kind of a TWA museum.”

And of course, that era is also when stewardess uniforms—and, in fact, every uniform associated with airlines—were fabulous.

“The uniforms from the ’40s and the ’50s are very conservative,” Muskiet says. “They actually all looked alike, with a white blouse, a skirt, a jacket, and a little hat. I prefer the diversity of the ’60s because everything was possible—a lot of colors, a lot of different patterns, psychedelic prints, blouses with flowers or stripes, and belts. Of course, the stewardesses were used to attract male passengers because sex sells. They had to wear short skirts and hot pants, but back in the ’60s, that was in fashion.”

In 1967, American Airlines adopted a mod look for its uniforms. (Via Paper Mag)

Very few young women who applied to be a flight attendant actually got the job; it was a position as coveted and competitive as becoming a model or a pageant winner. Being hired as a flight attendant, the narrative went, validated your beauty and poise and, as a reward, you got to travel the world. In the 1960s, as in the ’30s, stewardesses also had to be single, childless, and within a narrow age range. A 1966 “New York Times” classified listed the qualifications for a flight attendant job: “A high school graduate, single (widows and divorcees with no children considered), 20 years of age (girls 19 1/2 may apply for future consideration). 5’2″ but no more than 5’9″, weight 105 to 135 in proportion to height and have at least 20/40 vision without glasses.”

Ruth Carol Taylor, the first African American stewardess.

“You had to have a certain look, a certain height, a certain size,” Muskiet says. “You had to be young, free, single. You had to be Miss Universe or Miss World. Only a few girls were hired, so they were very fortunate. They lived this glamorous life because only a few people were able to fly, and flying was really something special back then. Those girls really lived a life a lot of people dreamed about.”

Before the 1950s, to fit into this rigid beauty standard in the United States, stewardesses had to be white. According to BlackPast.org, a young African American nurse named Ruth Carol Taylor started to push against this discriminatory practice in 1957 when she applied to be a flight attendant at TWA. The airline turned her down for the job, and she countered by filing a complaint with New York State Commission on Discrimination. Then, she heard that Mohawk Airlines, a local carrier serving the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, wanted to hire minorities as stewardesses, so she applied there. She was hired and flew as the first African American flight attendant on February 11, 1958. Chagrined, three months later, TWA hired Margaret Grant as the first black stewardess for a major U.S. airline. Taylor had successfully broken the race barrier.

In 1966, Emilio Pucci designed psychedelic catsuits for Braniff flight attendants. (Via Museum of Flight)

Because no one tried to hide the fact that flight attendants were there to be eye candy, big-named designers had a fun time dressing them up and coming up with sexy new gimmicks to promote air travel. In 1968, Jean Louis gave United Airlines stewardesses a simple, mod A-line dress with a wide stripe down the front and around the collar, and paired it with a big, blocky kefi-type cap. During the ’60s and ’70s, Pucci designed five different uniforms for Braniff International Airways.

“If you look at the Pucci uniforms, you can’t imagine that women wore these items,” Muskiet says. “There was even a space helmet, like a plastic bubble. It was used when it was raining outside, so the hat and hair wouldn’t get wet. Braniff also had something called the ‘Air Strip’ in 1965. During service, the stewardesses would take something off to reveal a different layer and a different look underneath. They might be wearing a skirt and remove it to show off their hot pants beneath.”

In 1965, Pucci gave Braniff stewardesses a hat that tied around the neck and a “Space Bubble” helmet to protect the hat from the rain. (Via TheGlassBox.typepad.com)

The stewardess image reached its height of sexualization, becoming a collective cultural fantasy that airlines shamelessly promoted through their advertising. The dark side of this trope was that women who got this prestigious position were often subjected to sexual harassment from drunken passengers, who might pinch, pat, and proposition the stewardesses while they worked, according to Kathleen Barry’s Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants.

Some of the gimmicks were just plain silly. TWA debuted paper stewardess serving dresses in 1968 to reflect the regional cuisine that was being served onboard. The four styles included “British wench,” “French cocktail,” “Roman toga,” and “Manhattan penthouse pajamas.” These dresses were made of a fabric-like paper that’s a little tougher than the paper you write on. “They were disposable so the flight attendants would only wear them once or twice,” Muskiet says. “Funny, but at the same time, very impractical.”

A TWA ad from 1968 shows flight attendants in their cuisine-themed paper uniforms.

Such whimsy didn’t last long. In the United States, the 1970s deregulation of the airline industry caused the price of airline tickets to drop, and new bargain airlines joined the market. As a result, more and more people were able to fly to their destinations, but the luxurious perks of air travel and goofy stunts like paper serving dresses were first things to get the ax.

“Before deregulation in the mid-’70s, the government would set the fare and the routes,” Lappin says. “It wasn’t really until deregulation that discount airlines like People Express and Southwest Airlines could change the economic model. That’s a process we’re still working through. But the upshot of it is we don’t think much of flying anymore. It’s not a big deal. Everybody does it. So the experience has changed quite a bit.”

A 1965 ad promotes Braniff International’s Air Strip gimmick.

Around the same time, the women who worked as stewardess in the United States were getting fed up, according to Barry. They organized the Stewardesses for Women’s Rights feminist group in 1972, and two years later, former flight attendant Paula Kane published her tell-all, Sex Objects in the Sky: A Personal Account of the Stewardess Rebellion. Through strikes, Title VII lawsuits, and campaigns, stewardesses protested their exploitation, demanded to be taken seriously as professionals (including better pay and benefits), and fought against discrimination based on sex, beauty, and age.

All this activism led to better compensation for flight attendants, looser restrictions on age and weight, and men joining their ranks. The progress meant the end of the tiny, colorful shift dresses, which were replaced by professional-looking suits with skirts past the knee in earth tones.

“By the ’80s, you had wide shoulder pads and wide baggy dresses with very long skirts,” Muskiet says. “In terms of fashion, the ’80s were a very ugly time. Yves Saint Laurent did a Qantas uniform in the ’80s, and even though he’s a top designer, it’s a horrible uniform.”

In a 1970s promotional photo for United, flight attendants wear muumuus, aloha shirts, and leis onboard a flight to Hawaii. (Via Museum of Flight)

Still, in the ’70s and ’80s, airlines like American, United, and Western maintained a bit of costume playfulness during their flights to Hawaii and Tahiti: Flight attendants would don muumuus and aloha shirts during the service. “It’s always nice to fly to Hawaii, and to see the cabin crew wear Hawaiian attire,” Muskiet says. “It’s like a different atmosphere. But it costs a lot of money to have different uniforms on flights to Hawaii. Now that airlines are trying to save money, it’s gotten to be too expensive to do that.”

During those decades, airlines like Thai Airways and Singapore Airlines started expressing their national identities through their flight-attendant uniforms. Female flight attendants for Thai still wear modern purple suits outside the plane, but change onboard into traditional silk Thai dresses. Other airlines honor their country’s traditions that require women to cover their heads, hair, or faces.

Today, female flight attendants for Malaysian Airlines wear a uniform based on the traditional sarong kebaya. (Via Paper Mag)

“In the Far and Middle East, you have different rules for what’s appropriate to wear,” Muskiet says. “In the Middle East, quite a lot of airlines, like Emirates, Gulf Air, and Oman Air, have stewardess uniforms with a hat that has a veil attached. For airlines like Singapore, Garuda, and Malaysia, women wear the long sarong kebaya, which is also a national piece of identity. It depends on the country the airline is from and what they think is important.”

But if you spend any time perusing Uniform Freak, you’ll notice styles and motifs recurring at airlines all over the world, from the 1960s shift dress to the evergreen Chanel-style suit and pillbox hat. Scarves come in a wide array of colors and patterns, and sometimes feature airplane motifs or the airline’s logo. Today, skirts are shorter than they were in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but women often favor pants. Most men and women working as flight attendants for the top U.S. carriers like United and American are required to wear navy blue suits or dresses.

In the 1960s, Pierre Cardin designed a uniform with a veil for Pakistan International Airlines. (Via History of PIA)

“Today, you have different types of women working as flight attendants—young, old, tall, small, fat, skinny,” Muskiet says. “So you have to think about a uniform that suits everyone. Uniforms have to be professional, and hot pants and go-go boots are not really professional. Times have changed.

“Especially in the United States, all the uniforms look alike because they’re all navy blue,” he continues. “When you have five or six different airlines, you hardly see the difference; only the wing on the jacket is different. There’s barely any color. In the ’60s and in the ’70s, you have so many different colors, like green, red, and orange, and now airlines are afraid to use color. I think that’s a bad thing. The United States had great uniforms in the ’60s and the ’70s, but now it has completely changed.”

Some airlines have even loosened up their flight-attendant dress code from professional to casual, with polo shirts, baseball caps, and baggy nylon jackets as uniforms. “It works for the low-budget airlines,” Muskiet says. “People just buy a ticket, jump on the plane, get one drink, and that’s it.”

In the 1990s, discount airlines like Southwest, left and right, and Austria’s Lauda Air, center, went casual. Lauda Air’s baseball caps had the destination embroidered on the front. (Via Uniform Freak)

Muskiet is particularly fond of airline uniforms that pay attention to little details. “I like it when you have little logo buttons,” he says. “When you have a green jacket, some airlines will have green plastic buttons, but others will have beautiful silver or gold color buttons. That makes a huge difference. I don’t like white blouses. When a blouse is white, I think it should have a print, maybe with little flowers, stripes, or an airline logo. The details are important. You can create different looks with accent pieces like scarves, vests, and little hats.”

Jean Louis designed this A-line dress with a kefi hat for United in 1968.

Muskiet loves the United Airlines uniform from 1968, the blue and beige Pan Am uniforms with a bowler hat from the ’70s, and the 1970s Iberia uniform from Spain— which has a cool yellow, blue, and green abstract sunset print on the dress. However, his sentimental favorite is the KLM uniform worn from ’75 to ’82.

“I am really pleased to have that uniform because when I was a kid, the stewardesses would wear that particular uniform,” he says. “It reminds me of my childhood, and the many times I flew KLM with my mother to the United States and within Europe.”

For Lappin, his favorite ramp jackets were made for airlines that don’t exist anymore like Pan Am or TWA, and the ones that feature logos that aren’t used anymore.

“You un-self-consciously end up capturing these moments in time,” he says. “I have a Northwest Airlines jacket. When I got it, I was like, ‘Northwest Airlines, eh, whatever!’ But two years later, Northwest got acquired by Delta, and now Northwest is gone. America West was acquired by US Airways, so that’s gone. It’s a very dynamic and unstable industry. So at any given moment, the things you see are reflective of where the industry was at.”

Naturally, even the ramp jackets were cooler in the ’60s—shorter, better-fitting, and often featuring snappy, colorful stripes.

This uniform for the Spanish airline Iberia was worn from 1972 to 1977 and is among Muskiet’s favorites in his collection. (Via Uniform Freak)

“Most ramp jackets from that period tended to be pretty short, unless they were winter weight, in which case they got long,” Lappin says. “You know the classic Dickies mechanic’s jacket? They’re that sort of a style. Dickies still makes those jackets today, and we consider them kind of a classic design. The vintage airline-ramp jackets are analogous to other kind of jackets that people collect, like beer-distributor jackets. They’re pretty similar because they were doing a similar kind of work.

“My favorite ones are from Pan Am in the late ’60s,” he continues. “They look kind of mod, thanks to the cool color scheme, and the Pan Am patch is on the shoulder around the arm, in an almost military style. The jacket looks like something out of a ’60s sci-fi movie. It’s pretty awesome.”

In the 1960s, Emilio Pucci designed uniforms for the Braniff ramp crews, but these white jumpsuits only survived one month of dirty work. (Via Braniff Pages)

The contemporary jackets just aren’t that interesting, Lappin explains. “Most of the airline ramp jackets today are that kind of baggy, all-weather Gore-Tex long jacket that doesn’t really have a shape to it. The designs are screen-printed, and they don’t have embroidered patches anymore. I don’t have much from the last 10 years partially because I haven’t really seen much that I felt like I was dying to have. I have a couple of newer United jackets, and I’ve never worn them. It’s less about the airlines themselves and literally about the style of the jackets.”

Collecting flight attendant and pilot uniforms are widely respected subgenres in the whole field of aviation collectibles. But the first time he visited an airline collectibles show near San Francisco International Airport, Todd Lappin learned that his ramp-jacket hobby made him an outlier.

“I used to joke that if you felt that comic books were becoming too mainstream, then you should probably head over to the airline collectibles show for a little dose of old-school subculture,” Lappin says. “I would ask around for ramp jackets, and I would just get these weird looks from the people who had set up tables there. There are very distinctive strains within the airline-collectibles world: people who collect glassware, people who collect safety cards, people who collect amenity kits, people who collect airplane models. But one person, I remember when I said I was looking for ramp jackets, he shook his head and looked at me like I was sad and pathetic and said, ‘Oh, I’ve never heard of that one before.’ So it’s not really a thing even within the subculture of the subculture of the subculture. It’s like you’re a geek among geeks.”

Lappin shows a Pan Am work shirt while wearing a mod-style Pan Am jacket from the late ’60s that he describes as “something out of a ’60s sci-fi movie.” (Photo by Lisa Hix)

But Lappin did meet one other ramp-jacket obsessive. When Lappin was hooked on hunting for ramp jackets, he’d see a jacket similar to one he already had, but because it was slightly different, he wanted it. And then he’d find himself in a heated competition on eBay.

“There was one other guy I was always bidding against, and we actually became friends, cyber pals,” he says. “At one point, I sent him a note about a jacket, and he said, ‘Jeez, how many of these things can you own?’ Then he said, ‘Wait a minute. How many of these things can I own?’ and we had a laugh. But he has a similar practical thing about it. He thought they were fun to collect, but he liked to wear them. He said they’re really good for wearing when he drives around in his convertible on cold days.”

Lappin says he’s noticed the airline collecting hobby is on the rise, which can be seen with the Twitter hashtag #avgeek, for “aviation geek.” “What #avgeek means is that you don’t necessarily work in the industry,” he says. “Even when I was super-obsessed with ramp jackets, nobody who didn’t have some sort of relationship to the airline industry seemed to be into collecting these aviation memorabilia. Everybody was either the present employee or an ex-employee. But now there’s this notion that actually you don’t have to have been an employee of an airline. There’s just an aesthetic to it that people appreciate.”

A flight attendant poses in her Pacific Southwest Airline uniform in 1973. (Via Museum of Flight)

Muskiet could fill up a whole museum with his flight-attendant uniforms, but he doesn’t know if he could stand the separation anxiety. “If I put them in a museum somewhere, whether it’s here in Holland or somewhere else in the world, I’m not with my uniforms and it doesn’t feel okay,” he says. “At the moment, I have 24 uniforms in a museum in Saõ Carlos in Brazil. Those are duplicate uniforms. So if something happens, I have an extra set at home in my collection. This museum—the TAM Aviation Museum—flies me from Amsterdam to Brazil each year so I can bring 12 new uniforms and take back 12.”

“In the ’60s, they didn’t just think about the planes. They were thinking about how the uniform looks and how the fuel truck looks when it’s sitting next to the airplane.”

Even having 1,275 uniforms isn’t enough. Muskiet loves the thrill of the chase, particularly since the uniforms he’s looking for don’t just pop up on eBay or surface at flea markets.

“You really have to talk to people to get uniforms,” Muskiet says. “It’s like a little adventure. If you could buy them in a shop, it would be a different story. But you have to write letters, and you have to ask permission. When I travel somewhere, I go to the offices and I try to talk to people into giving me a uniform. It’s a big challenge every time, so it’s a really a kick when I achieve something. It’s like ‘Yeah!’ and I go home like a little happy boy.

“Sometimes I receive emails from airlines, and they offer me a uniform because they know about my website,” he continues. “They’re like, ‘Oh, we would feel very honored if you put our uniform on the website, too.’ But usually I have to ask for it. It depends on who you deal with, which airline, the person, the regulations, everything.”

After coveting the current Korean Air uniform by Gianfranco Ferre, Muskiet scored one this summer.

Of course, in his quest, Muskiet has a few holy grails. “There are some uniforms I would really like to have,” he says. “One is Royal Jordanian, called Alia from Jordania. It’s a uniform that was used in the ’80s. I still haven’t found it. I need one missing piece from the 1970s Japan Airlines uniform, the bodysuit is missing. It’s a striped body suit, red with white or blue with white.

“I hope that one day someone will send me an email, and they will offer the bodysuit to me,” he says. “That’s how it usually works when I think of something. Maybe it takes a little while, but then I receive a message and someone offers it to me. And it’s really scary. That’s what happened with the Pan Am uniforms. That’s how I got the Japan Airlines uniform and several items that I was looking for. I know I will find it. With positive thinking, things come your way.”

A variety of TWA stewardess looks: 1968-1971, left; 1944-1955, center; and 1967-1968, right. (Via Uniform Freak)

Even though Lappin has quit accumulating ramp jackets, he still wears them biking around San Francisco, which is known for its fickle fog and microclimates within the city. The vintage jackets from various airlines are slightly different weights and thickness, and some even have zip-in linings, so they’re well-suited to the weather. If the jacket has a clear plastic pocket for an I.D., Lappin will sometimes slide an old boarding pass in there.

“It’s a real conversation starter, especially when I’m wearing a Delta Airlines jacket,” he says. “Often, I will have people telling me that I lost their bags. They know it wasn’t me, but they’re like, ‘That goddamn airline lost my luggage.’ I hear that all the time.”

Lappin holds up a winter-weight Pan Am jacket. (Photo by Lisa Hix)

(See all 1,275 looks from 475 airlines in Cliff Muskiet’s flight-attendant-uniform collection at his Uniform Freak web page, or follow his new acquisitions on his Uniformfreak Facebook page. To see other uniforms, visit the Museum of Flight in Seattle. To read more about flight-attendant history, pick up Paula Kane’s “Sex Objects in the Sky: A Personal Account of the Stewardess Rebellion” and Kathleen Barry’s “Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

If 'Pan Am' Takes a Nosedive, It Won't Be For a Lack of Authentic, Vintage Props

If 'Pan Am' Takes a Nosedive, It Won't Be For a Lack of Authentic, Vintage Props

Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free

Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free If 'Pan Am' Takes a Nosedive, It Won't Be For a Lack of Authentic, Vintage Props

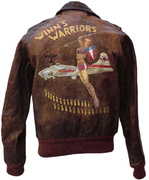

If 'Pan Am' Takes a Nosedive, It Won't Be For a Lack of Authentic, Vintage Props WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Aviation MemorabiliaFrom the start of regular U.S. passenger service in 1914, travelers have sa…

Aviation MemorabiliaFrom the start of regular U.S. passenger service in 1914, travelers have sa… 1960s DressesAs with everything else, the 1960s turned the fashion industry on its head.…

1960s DressesAs with everything else, the 1960s turned the fashion industry on its head.… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I was there and it was great fun. Pan American World Airways deserved to live because it was the leader in so many ways. She will be missed as long as we have memories.

I truly miss the Legacy airlines like TWA, Eastern, Ozark and Braniff.

Today I must fly United or Southwest, but it is like bus travel now.

I am glad my daughter flew as a child in the 1980’s-’90s, and knew

how much more elegant air travel was, before 9/11. Airports today

are like Gymnasiums with poorly dressed and impatient folks, and

some “Flight Attendants” with un-caring waitress attitudes. But I

still find many professionals that love and perform their jobs well.

Please save an Isle Seat for me. Thanks.

When I quit my “stewardess” job in 1967, I gave my entire uniform to the Goodwill!! Can’t believe I did that… Years later, I worked for Northwest/Delta. Saved all those uniforms pieces. But, I am still looking for the Pan Am Don Loper uniform of 1967. Know where I could find it..Hat also? Enjoyed the article. Thank you. Phyllis Miller

I distinctly remember reading a joke in Reader’s Digest some time in the 70’s that said since United Airlines was having their stewardesses wear mini-skirts their new slogan was going to be, “Fly the friendly thighs of United”. We’ve come a long way baby.

This is what I call a life-giving article. It took me back to the years when air travelling and being taken care by really good lucking and handsome women, was the cream ot the coffee, the Napoleon Brandy of the brandies and the Tower of Pisa.

Thanks for giving me some joy in my life; but a very important one.

José Luis Belmar

My mother Joy Stokes designed the very first uniform for the Bahrain based, Gulf Aviation back in 1967, and the first uniform when Gulf Air was formed in 1973, a beige trouser suit uniform. Unfortunately I cannot post the pictures here. However if you go to the Gulf Air Face Book site or my ‘Gulf Aviation – the original Gulf airline’ FB site you should see them.

I flew worldwide both as a child-young adult and as an adult, during the 50’s through the 70’s. As a child I remember being allowed to go forward to the flight deck and have the Captain and flight crew do a show and tell and sign my flight-club logbook. That will never happen again. It was mostly BOAC, British Air, Pan Am, and about a dozen others. You were treated like royalty even in coach. Everyone from flight crew, flight attendants, and ground personnel, were professional, and did a great job while looking very good at it. The flight attendants were nice to everyone. Passengers likewise were clean and well dressed, and for the most part well behaved. I have not flown since then for many reasons, but even by the mid to late 70’s the bloom was off the rose. I think Deregulation of the carriers really caused the end of the Golden Era of air travel. I cherish those memories, and realize those times will never come again. Mores the pity.

When I was a kid – when McCoy Air Force Base was the airport for Orlando & before Disney – we used to love to see the National stewardesses stroll by in their bright citrus colored uniforms – So glamorous! In the mid to late 60s, it seemed like the skies were the limit for excitement, fun & glamor.

“Jet airliners like the C-69 Constellation, the Boeing 707, and the Douglas DC-8 ”

A fun article, but, one of these items is not like the others: the Lockheed Constellation (C-69 was a military version) was a propeller plane powered by four piston engines.