Fast fashion might seem like a modern invention, but in the turbulent world of 18th-century France, when Marie Antoinette was calling the shots, fashion moved at light speed: In an era when several artisans would be called upon to labor over a single garment, styles shifted by the hour, rendering fashion magazines, which were printed every 10 days, outdated before their ink was even dry.

“Fashion itself went out of fashion. Nobody wanted to look like they were trying too hard.”

Not unlike today, the streets of Paris in the 18th century were filled with people wearing flashy outfits referencing politics and pop culture. Trendy hats, hairstyles, and other accessories signaled that you were in the know. During the 1780s, the aristocracy of Europe’s most powerful country even started slumming it with simpler, peasant-inspired looks.

But in 1789, the French Revolution brought the fashion industry to its knees, and as political tensions mounted, wearing the wrong outfit could be a fatal mistake. By this time, France’s economy had begun to falter, in part due to debts incurred by supporting the American Revolution (along with King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette’s extravagant lifestyle). Following years of poor harvests, rising food prices, and an inequitable tax structure, unrest among the working classes boiled over, leading to a bloody decade that cost members of the monarchy their lavish wardrobes, and often their lives. As a result of the French Revolution, the country’s social and political structures were reshaped around new ideals, which novel fashions helped promote.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell’s new book, Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, covers the French fashion industry at this crossroads, caught between the pull of ostentatious luxury and the more prudent values of democracy. We recently spoke with Chrisman-Campbell about the myriad ways French fashion reflected the country’s tumultuous politics.

Top: An illustration from 1778 of the “Coiffure de l’indépendance,” a hairstyle referencing the American Revolution. Courtesy the Musée Franco-Américain. Above: All eyes on the young Marie-Antoinette playing the harp at court in this detail from the 1777 painting by Jean-Baptiste-André Gautier d’Agoty.

Collectors Weekly: Why was French fashion so widely imitated during the 18th century?

Campbell: One of the fascinating things about the late 18th century is that it has so much in common with the fashion industry today, yet the clothing is all so alien and wonderful to look at. But we actually have to go back to the 17th century, because Louis XIV was the one who invested heavily in the French fashion and luxury-goods industries. This was his version of an economic stimulus plan. He knew it was good for the French economy both at home and abroad, so he publicized French styles through fashion plates and magazines.

As a result, French clothing and textiles were technically and stylistically superior, and were recognized as such throughout Europe and beyond. By the late 18th century, the fashion industry in France was a well-oiled machine. The spread of literacy, print media, and improvements to the postal system made that possible and fueled the dissemination of French fashion throughout Europe.

Collectors Weekly: How did the Enlightenment impact clothing trends in France?

Campbell: Fashion and ideas were spread together, so it’s often difficult to tell which came first. Fashion took inspiration from current events, and fashion, in turn, helped spread Enlightenment causes like small-pox inoculation, hot-air ballooning, and American independence. These were all cultural touchstones that found their way into fashion.

For example, the Montgolfier brothers invented a hot-air balloon that was all over the news in the early 1780s, and many fashions referenced Montgolfier. There were items that either actually looked like a hot-air balloon, or things that had nothing to do with hot-air ballooning, but used the name because it was trendy.

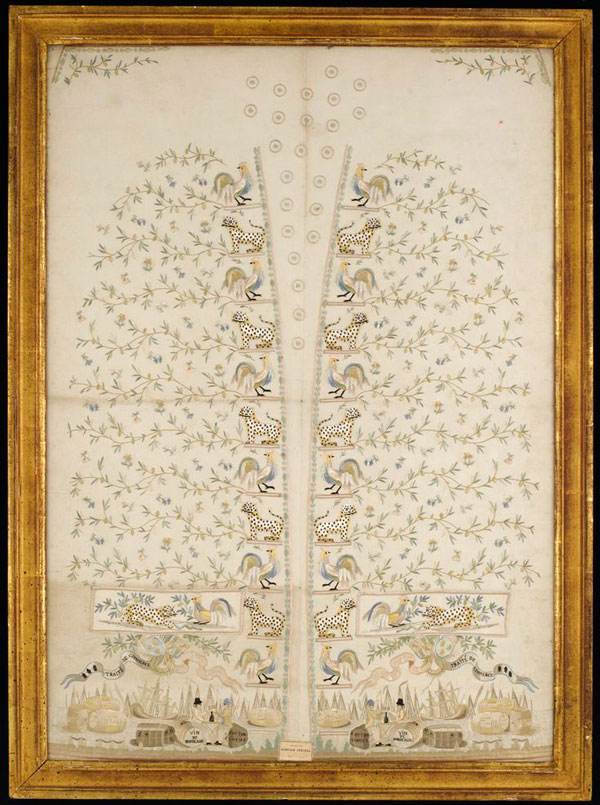

This embroidered panel for a man’s waistcoat, commemorates the Eden Treaty of 1786, an economic agreement between Britain and France. Image courtesy the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Collectors Weekly: Why did Marie Antoinette embrace fashion while prior queens had not?

Campbell: It was partly personal and partly cultural. Previously, royal mistresses had been the leaders of fashion. They had the money and the position but no accountability. They could spend as much money as they liked and wear anything they wanted. In contrast, French queens had always dressed magnificently but within the confines of very rigid court etiquette, and they were also answerable to the royal treasury. So in general they followed fashion rather than leading—they didn’t want to rock the boat.

But then Marie Antoinette comes along. Louis XVI didn’t actually have a mistress, so there was a void in the fashion hierarchy. Marie Antoinette was enamored with the vibrant Paris fashion world, as everyone was at the time. Paris had replaced Versailles as the center of society and style, so she wanted to take advantage of the wealth of talent there in Paris, rather than having one official dressmaker who only dressed her, which is what previous queens had done.

Collectors Weekly: How did images of the Queen’s garments spread among the public?

Campbell: Marie Antoinette was used as a model for fashion plates, though they were unauthorized, of course. Some would actually identify her and others just featured a woman who looked a lot like the Queen. This is true with other royal women as well, like her sisters-in-law. It was only at this time, in the 1770s, that fashion magazines began to be issued regularly. Up until then, the images could be found in newspapers or collections of fashion plates.

The caption for this 1781 fashion plate claims this duchess in courtly dress was very close with the Queen. Image courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By the 1770s, you had fashion magazines coming out every 10 days, not just every month like we have now. They needed something new to advertise, and the fashion industry responded to this by issuing new fashions. There were a lot of jokes about how your servant or dressmaker might steal your fashion magazine and by the time you’d get a new one, the clothes were already out of date. Or by the time magazines were delivered to Germany, the styles were out of date because it took 10 days to get there.

“Once the King and Queen start dressing like everyone else, it’s only a matter of time before people see them as mere mortals.”

Fashion magazines were very widely read, much more than their small circulation would imply—subscribers were limited to the one percent of the one percent, this elite Parisian courtly class that was driving fashion at the time. But because Paris was such a melting pot, laborers and artisans were living side by side with these aristocrats. The magazines were passed around and shared, and even servants got their hands on them. They were all copying these styles to the extent that they could.

There’s a lot we don’t know about how fashion magazines got access to the royal court. In some cases, it’s clear that what they were printing was not actually what was worn because when you look at a surviving dress, it had a different seam here or a different belt there. So in some cases, it’s clear they were either looking at portraits or maybe watching what was being worn from a distance.

However, the editors often made a point of saying a specific outfit was worn by a fashionably dressed woman walking in the Palais-Royal, and places like the Palais-Royal or the Luxemboug Gardens were public domain where people of different classes mixed freely. These magazines were really careful to say when something was actually worn—the duchess wore this, we saw it, and here’s where we saw it. They went overboard to emphasize that this was the latest thing, and they could prove it.

Michel Garnier’s 1787 painting, “A Fashionably Dressed Young Woman in the Arcade of the Palais Royal,” captures the catwalk quality of Paris’ popular public gathering places.

Collectors Weekly: How was the garment industry structured in 18th-century France?

Campbell: All fashion was couture in the 18th century, meaning it was all custom-made. So the client, typically a woman, effectively designed her own dress more or less in consultation with her milliner and her dressmaker and possibly even a mercer, who sold fabric. She would buy the fabric from one person, have it sewn by another, and then have it trimmed by someone else.

The system of trade guilds—called corporations in French—that regulated the fashion industry was Louis XIV’s innovation. He introduced this structure as a form of quality control: You had to do an apprenticeship and gain acceptance into the guild by your peers, which made sure everyone had the same training and high skills so that the French fashion industry maintained its excellent reputation. There were guilds for tailors, mercers, couturiers [dressmakers], and then, finally, a guild for marchandes de modes [milliner and accessory stylists]. Like modern-day unions, the guilds had a lot of power.

The marchandes de modes became very important because under the guild system, dressmakers could only trim a dress using the fabric from which it was made—that was the rule—whereas a marchande de modes couldn’t actually sew a dress but she could trim it with anything she wanted. In fact, the marchandes de modes eventually sewed certain garments as well. Legally, they weren’t supposed to, but in time you could buy a whole dress from them.

Fashion also became very topical with the rise of the milliner, since much more variety was possible. If you look at fashions of the mid-18th century, there’s a sameness to the designs—they used gorgeous textiles but the cut and trimmings didn’t change very much. By the 1770s, they were changing really quickly and there was this pressure to keep up, to know what was the latest accessory, hat, or trimming. By giving these accessories and trimmings topical names, the marchandes de modes ensured that they would go out of style as quickly as they had come in, bringing planned obsolescence into fashion.

François Boucher painted this scene in 1746. Entitled “La marchande de modes,” it depicts a milliner and client. Image courtesy the National Museum of Scotland.

Collectors Weekly: Since all garments were handmade, were most clothes worn secondhand?

Campbell: Probably thirdhand or fourthhand, actually. You had to be pretty well off to even afford secondhand clothing. There was a huge used clothing industry, with dealers or fripiers who would fix items up and resell them at flea markets, just as there are in Paris today.

“Over-the-top luxury went out of fashion in favor of this self-conscious simplicity.”

We know, for example, that Marie Antoinette gave her cast-offs to her ladies-in-waiting and sometimes they wore them, sometimes they sold them, and sometimes they made them into dog beds. This was replicated at all levels of society: When you finished with a dress or it went out of style, you would resell it or give it to your servants. In many cases, the upper classes and the working classes were, in fact, wearing the same clothes, maybe just a few years apart. As the pace of fashion began to speed up, there was a much bigger supply of secondhand clothing because the early adopters had already moved on.

Collectors Weekly: How did the pouf trend reflect current events?

Campbell: A pouf was halfway between a hat and a hairstyle. It was a thematic headdress made up of flowers, feathers, ribbons, gauze, and various props, reflecting events of personal or pop-cultural significance, including hit plays or scientific breakthroughs or political scandals. The illustrations of ship-shaped poufs are absolutely surreal. I started off thinking, oh, that’s just a silly caricature, but many of them were real hats. And they were not silly aristocrats being ridiculous; they were political statements referencing the American Revolution.

A fashion plate depicting a dress and headpiece in the style “à la Chartres,” including an over-the-top pouf, circa 1770s. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hats and hairstyles weren’t the only topical fashions, they were just the most prominent. Fans were often very topical. There was a fad for embroidered waistcoats for men with topical images or themes on them. You might have a gown trimmed “à la Chartres” in the style of the trendsetting Duchesse de Chartres. Or you might have a gown accessorized with a sash “à la caravan,” named after The Caravan of Cairo (La caravane du Caire), a popular Egyptian-themed opera written by André Grétry, the Queen’s favorite composer. There were multiple layers of meaning in some of these fashions.

Collectors Weekly: How did marchandes de modes become so powerful?

Campbell: The marchande de modes, or milliner, was a very new profession in the late 18th century. The guild of marchandes de modes was only incorporated in 1776, two years after Louis XVI came to the throne. It had existed before then, but wasn’t formalized yet. For the first time, fashionability was determined by trimmings and accessories more than cut, construction, or textiles, and these trimmings and accessories could be changed much more frequently and easily than the cut of a gown. This raised the stakes in terms of the pace and expense of fashion, making it much harder to keep up.

An engraving of Rose Bertin by Jean-François Janinet after her portrait, which was painted around 1780 by celebrated artist Louis Trinquesse, who also painted the Queen.

Most milliners were low-born women, like Rose Bertin, but Bertin was very unique in her success. Bertin was extremely talented, obviously, and one of her major clients was the Duchesse de Chartres, who was related by marriage to the King and was the richest woman in Paris in her own right. She introduced Bertin to Marie Antoinette, and once that happened, Bertin became unstoppable.

Bertin ruled over a vast fashion empire, and she flaunted it. She lived like a queen—she dressed magnificently and had her own carriage and liveried servants. Bertin also had the audacity to charge as much for her talent as for her materials. Previously, fabrics and trimmings made up the bulk of a gown’s cost with very little charge for the actual labor. But you can see the change reflected in 18th-century clothing bills, which always included the exact amount of fabric, the type of textiles used, and the cost because people wanted to know what they were paying for.

Many of Rose Bertin’s bills survive, so we can look at those and see what she created, but they’re not very descriptive. There’s a lot of detective work that goes into matching those with surviving garments. In very few cases do we know of a design’s original creator, and that’s often because it survived by accident. We do know who invented the so-called granny bonnet, which had a spring in it that could lower or raise the coiffure. That was Monsieur Beaulard, who was Rose Bertin’s great rival. Unfortunately, those things were not built to last, and none survive today, but we do have descriptions.

This British satirical etching commented on the French fashion for tall hairstyles, circa 1771. Image courtesy the British Museum.

Collectors Weekly: Was Bertin’s success a threat to the existing social order?

Campbell: It was in the sense that she became very rich and famous for a woman of low social class. The fact that she was welcomed into the royal apartments was really controversial. Previously, the Queen had one dressmaker who was not allowed to dress anyone else, and here was someone who was dressing all these other clients and the Queen. Marie Antoinette didn’t want her dressmaker or her hairdresser to be cut off from the Parisian fashion world, but at the same time, this opened the royal family to gossip and charges of impropriety because they were letting this “nobody” into the palace.

A dress designed to be worn at the royal chateau of Fontainebleau in 1783. Courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

But Bertin was very smart, and she actually survived the Revolution. Her career was effectively over at that point, but she did have a lot of foreign clients who continued to use her. She was devoted to Marie Antoinette, and she never betrayed her confidence or gossiped about her, so Bertin was painted with the same brush in many ways.

Collectors Weekly: How did mourning rituals influence mainstream fashions?

Campbell: It’s difficult to appreciate just how frequently people went into mourning in the 18th century—not just rich people, but everybody. Mourning was often a matter of etiquette rather than genuine sorrow. For example, a widow had to wear mourning attire for exactly a year no matter when she stopped feeling sad. If a member of the French royal family died, or any European royal family, really, because they were all related, the whole court went into mourning.

There’s a wonderful letter from Abigail Adams while she was living in Paris, in which she writes that poor Thomas Jefferson, the American ambassador at the time, had to go and buy a new silk suit because somebody died, so he had to wear black, but then a few days later he would have to get another black suit because you couldn’t wear silk after November 1st. There were all these matters of etiquette that had to be taken into consideration.

The frequency with which people had to wear black for mourning made it much more acceptable as fashion. People came to appreciate that black was elegant and practical, since it didn’t show dirt. By the late 1780s, though, mourning rituals began to lose their prestige along with other courtly formalities. People stopped wearing black for mourning, but they started wearing it every day.

Left, a magazine illustration from 1781 shows an outfit for court mourning. Right, a so-called “Polish” look from the same issue shows how mourning clothes were adapted for everyday wear. Images courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Of course, white and purple were also acceptable colors for royal mourning. There’s a theory that white gowns became fashionable in the 1780s partly because Marie Antoinette was constantly in and out of mourning during those years, so she was wearing a lot of white as an etiquette choice, but other people began imitating her fashion.

Collectors Weekly: Was Marie Antoinette trying to scale back her fashion expenses?

Campbell: I don’t think it’s fair to say she scaled back expenses because she still spent a fortune, but she did attempt to simplify her wardrobe. When Vigée Le Brun painted the famous portrait of her in a chemise gown in 1783, she was nearly 30. At the time, that was the threshold of middle age, so she was already changing her lifestyle. Her first daughter had been born in 1778 and her first son in 1781, so she was a mother. She gave up things like dancing and going to the theater as well as wearing styles that were considered youthful, like the feathered headdresses.

Related: How the Affair of the Diamond Necklace Ruined Marie Antoinette

On a practical note, her hair fell out after the birth of her daughter, so towering hairstyles were no longer an option. Marie Antoinette’s new look was more age-appropriate and suitable for her relaxed lifestyle, and it also harmonized with wider trends for pastoral simplicity and rustic elegance.

In 1783, Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun painted Marie Antoinette in a white chemise gown, at left, but public outrage over the image of the Queen in her “underwear” inspired Le Brun to redo the portrait in a more formal dress, seen at right.

Collectors Weekly: What were some of the styles popularized at this time?

Campbell: Chemise gowns or these white muslin dresses were hugely popular, along with straw hats like the one Marie Antoinette wore in the Vigée Le Brun portrait. Oddly enough, aprons became as common among the upper classes as they were among the working classes because they were viewed as this rustic accessory—though fashionable aprons were made out of embroidered silk gauze, a very impractical fabric for a practical garment.

An illustration of a typical white chemise gown from “Galerie des modes et des costumes français dessinés d’après nature” by Paul Cornu, circa 1780s.

In 1784, the enormous success of the play “The Marriage of Figaro” helped popularize this style. The play was set in Spain among a group of rustic servants, so this peasant-chic look was a way of paying tribute to the play and embracing the new simplicity that was trendy at the royal court in Paris. This was around the time when Marie Antoinette had a miniature model village built in the gardens of Versailles, so she could dress as a milkmaid, go to her dairy, and drink freshly drawn milk. She was not the only person doing this by any means: Many aristocrats had these model villages and enjoyed this kind of play at being a peasant. It’s horrifying, but she was just going along with the crowd.

Though Marie Antionette was still buying her expensive aprons from Rose Bertin, this simplified style was easier for the middle classes to emulate, particularly the muslin gowns made of cotton fabric imported from French colonies in the West Indies. Cotton was less expensive than silk, although not as cheap as you would think because it was still a novelty. But muslin was washable, and over time, the availability of cotton transformed fashion across the board because it made it possible for the lower classes to wear the latest fashions and clean their garments themselves.

Anglomania or the imitation of English fashion with garments made of plain, unembellished fabrics like wool was another big trend of the 1780s. Again, this contributed to the general simplicity of dress and worked against the embroiderers and silk weavers. The royal family adopted these fashions as well, and once the King and Queen start dressing like everyone else, it’s only a matter of time before people see them as mere mortals rather than monarchs.

In hindsight, it’s pretty easy to see the French Revolution in fashion even a decade before it happened. Even at the time, certain astute observers were commentating on this in a “what is the world coming to” kind of way. People were wearing black for everyday life, which was seen as a sinister omen. Throughout the 1780s, fashion workers like the embroiders’ guild or the weavers’ guild were constantly petitioning the King and Queen for help because they were losing so much business, as over-the-top luxury went out of fashion in favor of this self-conscious simplicity. The writing was on the wall.

![Muslin gowns, like the one depicted in <a href="http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/gallerie-des-modes-et-costumes-fran%C3%A7ais-41e-cahier-bis-des-costumes-fran%C3%A7ais-36e-suittes-dhabillemens-%C3%A0-la-mode-en-1784-pour-servir-de-suppl%C3%A9ment-au-6e-cahier-des-coeffures-xx260-chemise-%C3%A0-la-reine-352862">this fashion plate</a> from 1784, were sometimes called Chemise à la Reine, or "Slip [dress] of the Queen," after Marie Antoinette's pioneering style.](https://d3h6k4kfl8m9p0.cloudfront.net/uploads/2015/05/chemise-a-la-reine.jpg)

Muslin gowns, like the one depicted in this fashion plate from 1784, were sometimes called Chemise à la Reine, or “Slip [dress] of the Queen,” after Marie Antoinette’s pioneering style.

Collectors Weekly: How did factions like the Royalists and Republicans use fashion to identify themselves?

Campbell: After the Revolution, fashion became much more stratified, and you could tell someone’s political affiliation by what they wearing. But in the late 1780s, it was actually the upper classes who led the trend for simplicity, adopting the same fashions that would later be associated with the Republican revolutionaries.

This robe à l’Anglaise, or English dress, made from silk, circa 1785-1790, epitomizes the trend for simplified looks. Image courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The American Revolution was a huge cause in France, championed by the highest levels of society without any awareness that it could end badly, that getting rid of one’s King was a dangerous idea. France and the United States had a common enemy in the British, so the French naturally fell on the American side. But they were also swept up in the romance of these oppressed colonists throwing off the yoke of tyranny, a very popular idea in intellectual circles at the time. And, of course, this thinking eventually did lead to a revolution in France, but no one intended the transformation to be bloody. They wanted an American-style revolution and instead they got the Reign of Terror, this year of internal conflict and mass executions.

That’s partly why there’s nothing left of the royal wardrobes. People know Marie Antoinette had all these clothes, so where are they? Well, we know exactly what happened to them—they were completely destroyed and looted. I’m sure many of them are in historic collections, but we don’t know their provenance because they were stolen. Many of those we can trace are literally in pieces. I’m sure there are many beautifully preserved gowns out there that belonged to Marie Antoinette—I call them “fit for a queen”—but without a story attached we have no way of knowing.

The employees of the French fashion industry also had to flee, everyone from humble shoemakers to superstars like Rose Bertin, because their best clients either emigrated or died, and they could no longer make a living. But France’s loss was Europe’s gain, as many of these artisans settled in cities like London, Vienna, or Moscow, never to return. They took with them the skills and styles that had been admired throughout Europe, and now suddenly they were on everyone’s doorstep.

Collectors Weekly: During the years of the Revolution, what trends indicated political allegiances?

Campbell: The tricolor cockade, and really tricolor anything, became fashionable during the Revolution, to the point where it actually became required—you had to wear a cockade, or else. In many cases, it’s not clear if people were adopting this because they had genuine revolutionary feelings or because they didn’t want to get jumped on the street, since that’s what you were up against. People were literally being attacked in the streets for what they were wearing or not wearing during the Revolution.

Left, a bicorne hat from France, circa 1790, with a cockade of blue, white, and red ribbon. Right, this etching of Louis XVI from 1792 mocked the King by putting him in the costume of revolutionaries, include the red cap with its tricolor cockade.

Collectors Weekly: How did Paris regain its central position in the fashion world?

Campbell: The French fashion industry was decimated by the Revolution, and fashion itself went out of fashion. Nobody wanted to look like they were trying too hard. Even the leaders of government took pride in wearing more slovenly dress.

But just as Louis XIV had consciously established this industry in France, so did Napoleon after he became Emperor in 1804. He was very eager to reinstate courtly dress, splendor, and luxury in France because he knew it would help the struggling economy. He saw that the French economy had tanked largely because the fashion industry was wiped out. Napoleon didn’t want people to go crazy and bankrupt themselves, but he encouraged a certain standard of dress and luxury designed to revive the economy. He was a soldier not a fashion plate, yet he realized that this was essential to the health of the nation.

Fashion was and still is a very powerful form of self-expression, and it’s one that the government censors of 18th-century France couldn’t touch. It was also one of the few forms of self-expression open to women, who even at very elite levels had no voice in the government, church, military, or academy. Although the market for fashionable clothing was very small because new garments were so expensive, the influence of fashion was magnified by print culture, and it trickled down to the growing middle class and working class. Fashion could be a very dangerous thing.

This 1797 etching shows two couples mocking each other’s fashion sense, with the “nouvelle riche” on the left and the “ancien régime,” or old guard, on the right. Courtesy the British Museum.

(For more fascinating tales of 18th-century French fashion, check out Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell’s book “Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.”)

Everything You Know About Corsets Is False

Everything You Know About Corsets Is False

These Chopines Weren't Made for Walking: Precarious Platforms for Aristocratic Feet

These Chopines Weren't Made for Walking: Precarious Platforms for Aristocratic Feet Everything You Know About Corsets Is False

Everything You Know About Corsets Is False Sex, Power, and High Heels: An Interview with Shoe Curator Elizabeth Semmelhack

Sex, Power, and High Heels: An Interview with Shoe Curator Elizabeth Semmelhack Georgian JewelryThe Georgian period refers to a time of political upheaval between 1714 and…

Georgian JewelryThe Georgian period refers to a time of political upheaval between 1714 and… Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in…

Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Thanks for the great article on fashion and the French Revolution. I live in an area where there is a large Native American population and an item of dress that is popular amoung men is the ribbon shirt. One story I have heard to explain this ceremonial item is that after the Revolution surplus ribbon and decoration from France was sometimes sent with fur traders to the New World, to use as barter, hence the ribbon shirt. Do you have any information on this theory?

@Bonni Renike: I am Native American and I’m not so sure this is how the ribbon shirt came into being. As a young woman I didn’t see ribbon shirts being worn at powwow or for any ceremonial type event. Rather, what I did see were western shirts be in worn by dancers, tribal officials, etc. The ribbon shirts in my area are fairly recent in our history. Ribbon shirts came into popularity when the pow wow circuits came into full swing and we started contest dancing. Long ago our men work buckskin shirts decorated with long beaded strips down the front, back and arms. Since the Indians were forced to live within the boundaries of reservations and their weapons were taken from them and the scarcity of game there were no hides were to be had to make our clothing. Fabric took its place. We had very little money to spend on decorations and no furs to trade so no beads anymore. All decorating of apparel came into a standstill. We didn’t powwow either as we were forbidden to dance or practice any of our ceremonies. A long time went by and finally as little as 40 50 years ago we once again began to gather and dance. We wanted to look good and have pretty/handsome dance clothes we began to use ribbon to decorate with, beads were not so easy to come by then as they are now. The way I see it the ribbon shirts came into being as a replacement of the beautiful hide war shirts. The buckskin and ribbon shirts worn by the men are our best and our formal clothing such as the suits and tuxedos are. I may be wrong….these are simply my observations.

So that’s a reason to kill her? Then there are lot of people who should be dead nowdays.

I very much enjoyed this well researched and well written article. The artistic depictions and portraiture are wonderful as well. Very interesting regarding the tricolor cockade and various connotations of wearing such. Love getting this information. Keep up the great work!

marie Antoinette and her husband were both mentally retarded–they sold all their jewels-those that belonged to them and not the state, to donate to the American revolution–almost everything they did was misinterpered and they lost their heads-I am a cousin many times removed-but I know that they both loved the American revolution and the native americans.