This year marks the centennial of the Christmas Truce of 1914, in which pockets of German, British, and French troops along the Western Front laid down their arms to share cigarettes, bury their dead, and sing Christmas carols—in some places for a few hours, in others for several days. Between July 28, 1914 and November 11, 1918, World War I claimed upwards of 20 million lives. As a small pause in the carnage, the Christmas Truce was a fleeting moment of humanity amid unimaginable slaughter.

Naturally it was also a big story by the time newspapers in the U.K. got around to reporting it during the first week of January 1915. Papers from Aberdeen to Exeter published blurry photos of British and German soldiers posing stiffly for cameras in No-Man’s Land, the name given to the narrow ribbon of barbed wire, mud, and blood that separated the combatants holed up in their cold and soggy trenches. For a nation that had been led to believe its troops would be home by Christmas, but quickly realized how false that hope had been, the truce was a rare bit of good news.

Top: The Truce was front-page news in the U.K. Above: In one of the most widely circulated photographs of the Truce, Saxon-German regimental troops shared cigarettes with soldiers of the 5th London Rifle Brigade in Ploegsteert, Belgium, south of Ypres.

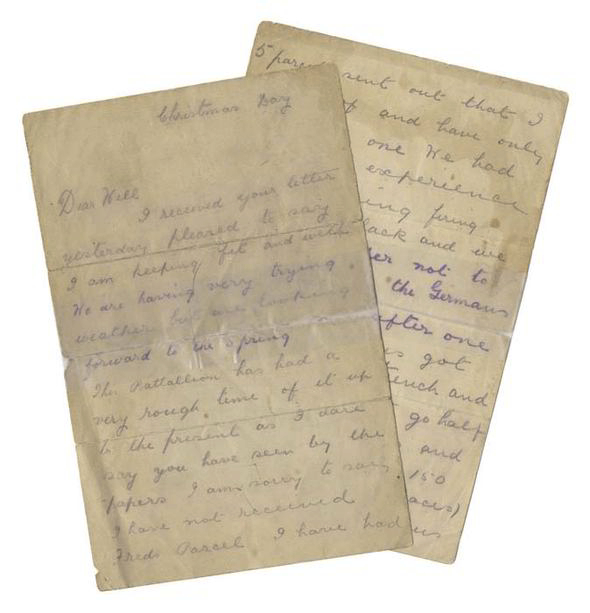

While the totality of the events on December 24 and 25 along the entire length of the almost 500-mile Western Front—from the coast of Belgium to the border of Switzerland—will never be known, the scores of letters sent home by British soldiers shivering in the trenches on the Allied side of the Western Front sheds light on a few basic facts. (You can read dozens of transcribed letters at Christmas Truce 1914, which is curated by journalists Alan Cleaver and Lesley Park.)

First, the rain that had plagued the troops for days on end had abated in the fields of Flanders, the northern part of Belgium, leaving the cold night air still and quiet enough for the troops on either side of the conflict to hear the stirrings of their enemies—in some places, British and German trenches were just a few dozen yards apart. In a letter published on January 9, 1915, in the Hertfordshire “Mercury,” Rifleman C.H. Brazier writes:

“On Christmas Eve the Germans entrenched opposite us began calling out to us ‘Cigarettes’, ‘Pudding’, ‘A Happy Christmas’ and ‘English – means good’, so two of our fellows climbed over the parapet of the trench and went towards the German trenches. Half-way they were met by four Germans, who said they would not shoot on Christmas Day if we did not. They gave our fellows cigars and a bottle of wine and were given a cake and cigarettes. When they came back I went out with some more of our fellows and we were met by about 30 Germans, who seemed to be very nice fellows. I got one of them to write his name and address on a postcard as a souvenir. All through the night we sang carols to them and they sang to us and one played ‘God Save the King’ on a mouth organ.”

British troops received a number of Christmas gifts from Princess Mary, including tobacco and a pencil made from a shell casing.

That the truce was initiated by the Germans is corroborated in many of the British-penned eyewitness accounts, although the reasons for the cessation of hostilities vary. At one end of the spectrum are letters describing a desire on the part of German soldiers to bury their dead, who were lying in No-Man’s Land after a particularly nasty battle the day before. In a letter home published in the Aberdeen “Daily Journal” on January 6, 1915, Lance-Corporal Imlah wrote:

“The German officers… said that they wish an armistice in order to bury their dead. After some conference it was agreed to grant the armistice, the reason being that we also had dead to bury… We were all glad of the halt anyway and soon we got started burying the dead. Any of our men lying near the German trenches were carried by the Germ to a ditch midway between the trenches where they were buried by us. Any of their dead on our side of the ditch were carried there to be taken away by the Germans for a burial. Our padre, who very fortunately happened to come up to the trenches that morning to wish us a Merry Christmas, arranged to have a service. After the burials were completed we lined up on appointed sides of the ditch, officers in front and burial parties in rear. I was very proud to be one of our party on such an occasion. Our padre then gave a short service, one of the items in which was Psalm XXIII. Thereafter, a German soldier, a divinity student I believe, interpreted the service to the German party. I could not understand what he was saying but it was beautiful to listen to him. The service over, we were soon fraternising with the Germans just as if they were old friends.”

When newspapers did not have photographs to work with, they published illustrations. The caption for this one read: “The Light of Peace in the trenches on Christmas Eve: A German soldier opens the spontaneous truce by approaching the British lines with a small Christmas tree.” In fact, most letters from British soldiers credit the Germans with starting the Truce.

Equally evocative are those letters, and there are many, that credit music for the onset of the truce. “Singing probably started the Truce off,” says Alan Cleaver. “The Germans celebrate Christmas Eve more than Christmas Day, so they started singing carols on Christmas Eve and the British/Allies responded with their own carols.” Indeed, many accounts tell stories of British soldiers hearing their German counterparts singing “Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht, Alles schläft; einsam wacht,” whose melody they immediately recognized as “Silent Night.” In a letter home published in the Norwich “Eastern Daily Press” on January 1, 1915, an unknown soldier writes:

“The truce came about in this way. The Germans started singing and lighting candles about 7:30 Christmas Eve and one of them challenged anyone of us to go across for a bottle of wine. One of our fellows accepted the challenge and took a big cape to exchange. That started the ball rolling. We then went halfway to shake hands and exchange greetings with them. There were ten dead Germans in a ditch in front of the trench and we helped to bury those and I could have had a helmet but I did not fancy taking one off the corpse. They were trapped one night trying to get at our outpost trench some time ago. The Germans seem to be very nice chaps and they were awfully sick of the war. We were out of the trenches nearly all Christmas Day collecting souvenirs.”

While many readers may have welcomed the news that for a day or so, anyway, their sons were not in harm’s way, the Truce did not sit well with everyone. In a letter to the editor published in the Aberdeen “Daily Journal” on January 9, 1915, an irate Scotsman writes:

“I am surprised and disappointed to think that British soldiers would have agreed to shake hand with murderers and thieves. Was all this done with the concurrence of their officers and will it be mentioned in Sir John French’s next dispatch? I doubt not. In the same issue of your paper where the handshaking is mentioned we read report of the French Commission appointed to investigate acts committed by the enemy in violation of international law that ‘outrages on women and girls have been of unprecedented frequency’ and ‘the soldiers and officers’ finished off the wounded and mercilessly killed the un-offensive, sparing neither women nor children’. Fie on ye, Scotsmen! There is not much of the boasted Highland Pride left in you when you would sell it for a German souvenir.”

Similarly, British soldiers write of agreeing to a truce with their Saxon-German counterparts, only to witness comrades being gunned down by more zealous Prussian-German troops, as in this anonymous account published in the Whitehaven “News” on January 7, 1915:

“We had a rather sad occurrence on Christmas Day. Directly in front of our regiment there were two German regiments. On our right was a regiment of Prussian Guards and on our left was a Saxon regiment. On Christmas morning some of our fellows shouted across to them saying that if they would not fire our chaps would meet them half-way between the trenches and spend Christmas as friends. They consented to do so. Our chaps at once went out and when in the open Prussians fired on our men killing two and wounding several more. The Saxons, who behaved like gentlemen, threatened the Prussians if they did the same trick again. Well, during Christmas Day our fellows and the Saxons fixed up a table between the two trenches and they spent a happy time together, and exchanged souvenirs and presented one another with little keepsakes. They said they did not want war, and think the Kaiser is quite in the wrong. They were continually falling out with the Prussians – they are the people who are the cause of the war.”

On December 5, 2014, the centenary of the Christmas Truce was marked at the United Nations with a mock football game. Here, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon takes a penalty kick for the cameras. Photo: Mark Garten, the United Nations

And then there is the story of the fabled football game (“soccer” in the U.S.) that allegedly took place between the opposing forces. “Football was almost certainly played between the Germans and British at one or two points of the front line on Christmas Day,” says Cleaver, “but some historians dispute this. It was probably more of a kick around. Football means more to us today than it did in 1914, and we know that boxing, cycling races, and other ‘sporting’ events took place during the truce.” Still, whatever the facts, the sport was a welcome respite for at least a few soldiers like Rifleman Smith, whose letter home was published in the Warwick and Warwickshire “Advertiser” on January 16, 1915:

“In the afternoon we even played football between the two lines of trenches, the Germans being interested spectators. These conditions remained the same all night and up to now but expect we shall soon be smacking into it again.”

In fact, by December 26, the new comrades whose differences had more to do with the colors of their uniforms than the content of their character, were ordered to train their weapons on one another once more—the war would grind on for four more bloody years.

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

What America Can Learn From Berlin's Struggle to Face Its Violent Past

What America Can Learn From Berlin's Struggle to Face Its Violent Past Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets Wartime LettersWartime letters are more than just sentimental family mementoes tucked away…

Wartime LettersWartime letters are more than just sentimental family mementoes tucked away… World War OneWorld War I coincided with numerous advances in technology, resulting in th…

World War OneWorld War I coincided with numerous advances in technology, resulting in th… ChristmasCollectible Christmas items range from antique hand-crafted pieces like blo…

ChristmasCollectible Christmas items range from antique hand-crafted pieces like blo… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article, best I have seen on the subject.