Illustrator Greg Theakston has retouched and reprinted the work of some of the most admired artists of the Golden Age of comics, more than 10,000 pages in all. In this interview, Theakston discusses some of these artists, including Jack Kirby and Basil Wolverton; casts a wary eye on the idea of comics as raw commodities; and explains Captain Marvel Jr.’s little-known influence on Elvis Presley.

Jack Kirby and Joe Simon’s Captain America gives Hitler a hard sock in the kisser in issue #1, which hit newsstands in December of 1940.

My older brother started bringing comics home in 1957 when I was around five years old. The whole form just fascinated me. Even at that age I was collecting. I still have a lot of those comics, most of which are from 1939 to about ’78. Some exceptional comics came out after that, but for the most part, that’s what I collect.

Some of the top guys worked during that period. I’d definitely put Jack Kirby at the top of the list. He codified what a superhero comic book was about. Before that, there really was no template. Then Kirby entered the business, showed his peers what he could do, and everybody just struggled to keep up. That’s pretty much the way it was for the rest of his career.

His first work appeared at the beginning of the Golden Age in about 1938. Comic books had been around since 1933, but most of them were just newspaper strip reprints. Once that reprint material was exhausted, artists and writers were hired to create new stuff. A lot of these people were just grasping at straws. They were largely inexperienced artists, but they were the best the comics business could afford.

Very quickly, though, new comics were routinely selling between half a million and three million copies. Keep in mind that’s at a dime apiece. They were competing on even financial terms with “Life,” “Time,” “Collier’s,” and “Saturday Evening Post.”

“Parents thought comics were dangerous.”

The publishers had extremely low overhead. The artists largely produced from their homes or their studios, so there wasn’t a lot of need for space. Once the work was in, all you needed was a cleanup guy and the editor. So the profit margin was enormous, which was why so many magazine publishers jumped in at the same time. They didn’t give a damn whether it was a comic book or “Liberty.” They were all selling off the same newsstand for the same 10 cents. That was the beginning of the Golden Age.

Collectors Weekly: Were people collecting Golden Age right from the start?

Theakston: At that point, comics were something to read, not necessarily something to collect. People didn’t think in those terms. It was a throwaway medium. It was printed as cheaply as possible and sold for the lowest possible price.

Kids always collected, but it wasn’t quite the same kind of rabid pursuit that developed in the 1960s. The storyline continuity of Marvel Comics in the ’60s promoted a collector’s sensibility. They were constantly referring to something that happened five issues back, and if you missed it, you wanted to see what it was.

Mail order became a successful part of the business as people ordered back issues of comics they’d missed. It was the first time that you could get whatever you wanted for a price. Prior to that, collecting had been a matter of luck or the ability to make a trade.

So comic book collecting really started around ’63 or ’64, when storylines and services began to galvanize the collecting communities. Most comic books of the day printed the addresses of the people who wrote fan mail. So you could write somebody, which unified fans and brought collectors together.

By the mid- to late ’60s, comic book conventions began to spring up around the country. Not only could you meet somebody with similar interests, but the conventions sold the comic books you’d missed. You could look at them and compare the prices with those of other dealers. So it became a much more hands-on way of collecting.

Collectors Weekly: How long did the Golden Age last?

Theakston: Well, there’s a lot of debate on that within the community. It’s generally believed that the Golden Age ran from 1938, when Superman debuted, to 1954, when the Comics Code Authority came into effect. After that, the contents of the books were carefully monitored by an organization that was funded by the comics industry.

The cover of Adventure Comics #75 from 1942 shows Jack Kirby’s Sandman, aided by his sidekick, Sandy, doing battle with Thor.

They opted for self-censorship because comic book publishers knew that if they didn’t take steps, they were going to be censored from the outside, which was the last thing anybody wanted. A Senate subcommittee had held hearings on juvenile delinquency in April of 1954. It had been televised and almost permanently tarnished the industry’s reputation. So they formed the Comics Code Authority later in the year.

In fact, there were some not-very-tasteful comic books produced during the early 1950s. Many of the comic book publishers had started out publishing pulps and dime novels. They knew that sex and violence sold there, they thought, “Well, what the hell. Let’s do it in comics.” A lot of publishers were squeaky clean, like Dell, which produced the Walt Disney books and movie adaptations. There was the “Superman” line, of course, and “Classics Illustrated.”

By the time the Comics Code Authority kicked in, a lot of the publishers who’d printed the most questionable material were already gone. They just jumped in, made a quick buck, and left, but everybody else was left holding the bag. I remember a mother telling me that comics would rot my brain. Parents thought comics were dangerous. That perception, combined with competition from television and the demise of mom-and-pop stores, made it very difficult for comics to stay profitable.

Collectors Weekly: Which publishers bore the brunt of those hearings?

Theakston: Primarily E.C. Comics put out by Bill Gaines. They were extremely gory, and yet sometimes charmingly ridiculous. The material may have been shocking, but it was well done. They were the top writers and artists in the business, doing some pretty grim stuff, but it was always a bit tongue in cheek.

Gaines probably lost his entire line because of the hearings and wouldn’t have survived had he not changed the format of “Mad” into a magazine instead of a comic book. That was one of the biggest successes in publishing history. It would routinely sell three to four million copies per issue, even though it was put together in a very small office with low overhead.

Collectors Weekly: Where did the name Golden Age come from?

Theakston: It’s like the golden age in Rome. It’s just a time period thought of nostalgically. In terms of content, a good 80 percent of the stuff done in the Golden Age was pretty awful, particularly the backup features, which barely made sense. But on the other hand, there were some shining moments.

The Dell line of comics was produced largely by the Disney artists themselves. In the Superman line, even the backup features were good. Fawcett, the people who did “Captain Marvel,” were always entertaining. Timely Comics, which published “Captain America,” were hit and miss, but generally a pretty good read.

In the ’60s and ’70s, when collecting started to take off, a lot of the people buying comics had bought the same issues off the newsstand when they were kids, so there was a lot of nostalgia to it. That was when you first started to see the prices go up because the people who bought them the first time had grown up and had a lot more money to buy them a second time.

Collectors Weekly: Were people collecting Golden Age during the ’60s and ’70s?

Theakston: No. I’d say the comics of the day were more popular because they were cheaper and easier to find. You could get them anywhere. In terms of collectibility, the Golden Age material was the rarest. Anybody could go out and buy six copies of the latest “Fantastic Four.” But try to find six copies of “Superman” No. 12. Having a nice set of Golden Age books was impressive because not many people did.

During World War II, superheroes routinely fought the Nazis, as Bill Everett’s Sub-Mariner did in the spring of 1941.

These days there’s less of a nostalgia factor—comics are viewed more as a commodity. Comic books are now graded and then placed into a plastic box. It’s called slabbing. It’s a widely practiced abomination.

You send it to the grader. The grader goes through it, grades it, and then locks it into a plastic box. The proof that it’s a commodity is they inspect it and grade it. Now this works wonderfully with baseball cards and coins because they only have two sides. You put them in a little plastic box, and you can still enjoy them. Once you slab a comic book, that’s it. The enjoyment factor is gone, and then it’s strictly a commodity.

The collector only cares that it accrues value. There are bragging rights to having the highest graded copy of something in existence. It’s not, “Boy, I get such a kick out of this,” it’s “Boy, I got the best one and you don’t.”

Part of the tragedy of modern comic book collecting is that it’s turned into a strictly investor situation. If you pay to have that book graded, you’ll never read it again. It’s gone. Sixty-four interior pages are now missing from humanity. There are some collectors who will crack them out of their cases—they are even called crack addicts. They don’t care that they were graded; they just want to see that book.

It’s really become a connoisseur’s hobby, and if you’ve got the right product on eBay, you can make a small fortune. Somebody is always looking to upgrade a copy or at least get their first copy of something. The better condition the book is in, the more people will be bidding on it and the higher the price. Frankly, I’m astounded at some of the prices comic books are fetching these days—six figures.

One of the reasons why they are so rare is World War II. Millions of comic books were sacrificed for paper drives to support the war effort. There are a number of Golden Age comics of which less than 20 are known to exist, making those very valuable. Plus, they weren’t designed to last a long time. They were printed on the cheapest paper with the cheapest presses and the cheapest binding to make a few extra pennies. Comics don’t age well by the very nature of their construction.

Collectors Weekly: How did Superman change the comic industry?

Theakston: Superman, who was created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, really pioneered the comic book story format, as well as the superhero genre. He was the first and the best. Once other publishers saw the figures, they said: “These things are cheap to make. Let’s get involved.” Suddenly there were superheroes everywhere. Having a picture of Captain America socking Hitler was something people had never seen before. It provided an outlet for people’s dreams, power fantasies that most conventional media simply couldn’t compete with.

This cover for “Wonderworld Comics” from February of 1940 shows why Lou Fine was one of the most respected artists of the Golden Age.

Up until Superman, comic books were primarily comic strip reprints. In a newspaper, it took 12 weeks to follow a story from beginning to end. Suddenly, here’s a story that you can enjoy in 12 pages. So the immediacy of the comic book story format really hit home.

Superman was also the first major costumed character to break through. As a result, he defined what comics were. It wasn’t just about cops and robbers or an orphan and her dog anymore. There were things depicted in comics that people had never seen before. They’d never seen an image of a guy lifting a car over his head or a rocket ship to the moon. Who ever thought about traveling to the moon?

Comics also had their own unique language and pace. In the newspaper strips, the first panel of every new strip rehashed what had happened in the previous day’s installment. That slowed down the storytelling. In a comic book, it was just bang-bang-bang, panel after panel, until the resolution.

There were far fewer constraints on how stories could be told in comics compared to newspaper strips. Comics were written and drawn by exuberant, young guys, and the stories were likewise young and rude, with an energy that you don’t see in other examples of popular culture of that period.

It was like a bunch of underground filmmakers had been let loose in a publishing company. They pretty much got to do whatever they wanted because there were no defined rules. The company didn’t give a damn as long as it sold a million copies.

It definitely was a novelty, especially during the War. Comics were being bought by the U.S. Government and shipped overseas to guys with nothing to do while they waited to go to war. A lot of comics were bought and read by adults during the war years, which ultimately led to romance and crime comics once people lost their appetite for superheroes. And some of the abuses in those genres resulted in the Comics Code.

Collectors Weekly: Can you give us a few examples of stellar Golden Age collections?

Theakston: There was a collection discovered in Denver called the Mile High Collection. Some guy had collected virtually every Golden Age comic ever published. Golden Age comics were printed on pulp, which contains acid. If they’re not properly stored, they get brittle, yellow, and fall apart. But this guy had stored them in racks in a cool, dry basement. It was the most pristine collection of Golden Age comics ever discovered, and it made the people who found it millionaires.

That’s an important aspect of Golden Age collecting, the pedigree. If it’s a Mile High copy, you know it’s one of the finest condition copies there is. So you want to advertise that it’s a Mile High. Another example is a comic from the Douglas Crippen estate. There was a huge find of comics through that guy, who penciled a D on the front cover of all of his comic books. So a Douglas Crippen comic has a value over and above what it is. Why that matters to anybody, I’ve no idea.

OOC—original owner collection—always gets people’s interest up. It means the collection probably hasn’t been picked over. If someone hung on to it for a long time, they probably took good care of it. Naturally the added value tends to work in favor of whoever owns the property.

Frankly, I couldn’t care less about where a book came from. And how much money a comic is worth is not what a comic book is about to me. I could give you an estimate of what my comic books are worth, but they’re not going anywhere, so what’s the point of even pricing them? I own them. They’re here. I’m done, and I’ll enjoy them when I want to. In fact, when I was really actively collecting, I was going for the lowest grade copies I could find. I wanted a comic book I could read 10 times and not worry about it devaluing.

Collectors Weekly: You mentioned Jack Kirby: Who were some of the other key artists of the Golden Age?

Theakston: Lou Fine was one of the top Golden Age comic book artists. Although he only worked for two years, a lot of the material he produced still exists because it was so good that fans hung around the office to get a piece of his artwork.

Jack Cole, the creator of Plastic Man, is also very well known, as was Basil Wolverton, who drew the famous Lena the Hyena portrait. It was in “Life” magazine. He also illustrated virtually the entire Bible in a very bizarre style in the ’50s. If you want to see the origins of Robert Crumb’s work, it’s in Basil Wolverton. Crumb, who is an underground artist, tends to be a curmudgeon with a weird streak. Wolverton was an ex-Vaudevillian, and that translated into his work, which was a bit daffier.

Bill Everett created the Sub-Mariner and worked steadily for decades. Then in the late ’40s and early ’50s, there was a second wave of guys who had been inspired by the first. They had more of an edge, were a little more sophisticated, and they had a template—tens of thousands of comic books filled with stuff to steal. In the second wave, there were terrific guys like Wally Wood, who worked consecutively on the first 110 issues of “Mad” magazine. There was also Al Williamson, a very fine line artist whose style was reminiscent of Flash Gordon’s Alex Raymond.

Frank Frazetta, who eventually became very famous illustrating paperbacks, movie posters, and record covers, got his start in comics. Everett Raymond Kinstler, who painted several presidential portraits, got his start in comic books. Roy Lichtenstein worked in comics briefly. Mickey Spillane won his spurs writing for comic books. A lot of guys that liked that kind of material cut their teeth there and then moved on.

Pay in the Golden Age was notoriously low, and that stuff was cranked out. If you’ve got six panels and three pages to do by the end of the day, you can’t slave over it and make it perfect. Consequently, a lot of it was formula. One of the biggest problems with Golden Age comics is that you read the same story six different times with six different characters. But getting the job done quickly was the top priority. It didn’t matter if it was great; it had to be at the printer by Friday.

Collectors Weekly: Did the artists also write their stories?

Theakston: Sometimes, if they were really talented and had a strong vision. Kirby, Jack Cole, and Wolverton all wrote their own stuff. But Lou Fine wrote very little. He was strictly an artist. It really just depended on the creator and how much control they wanted.

At first, not many of the writers were well known because credits were rarely given. You never knew who was drawing or who was writing. You’d recognize a style from another book: “I know that guy. He draws in squiggles.” Unless you reached some kind of star stature, you generally worked under a house name. If you were a writer and wanted to be known, you went to the pulps, not to comics.

Collectors Weekly: So fame came later?

Theakston: Yes. In the early ’60s, thanks largely to Stan Lee and Marvel Comics, everybody pretty much started getting credits, all the way down to the lettering. That’s when everything changed in terms of getting your due.

In the Golden Age, comics were often credited to a house name that was owned by the publisher. In some cases, if the artist was really talented, they’d let the person sign it. A lot of people, though, thought what they were doing was just garbage, so they didn’t want their names on it.

Now, you can find some of this information on the Grand Comics Database on the Internet. It’s trying to list every comic book ever published with titles, credits, and a cover reproduction. It’s amazing. All of the images there are public domain, and they’re free to anybody who wants to use them. For the most part the copyrights were never renewed because comics were monthly throwaways. Little did they know that there would someday be a market for reprints.

What this means is that a vast number of Golden Age comics are in the public domain. By the time the issues came up for renewal, the companies were either no longer in business or no longer doing comics. For example, Quality Comics’ entire output until 1955 is in the public domain because the owner went out of business and didn’t bother to renew it.

Collectors Weekly: Who were some of the other major publishers?

In the spring of 1941, “World’s Best Comics” #1 featured Superman, Johnny Thunder, Crimson Avenger, and Batman and Robin.

Theakston: National Periodical Publications had “Superman,” “Batman,” and “Wonder Woman”; Timely Comics published the “Human Torch,” “The Sub-Mariner,” and “Captain America”; Fawcett had “Captain Marvel” and “Captain Marvel Universe”; and Quality Comics released “Plastic Man” and “Blackhawk.”

Dell was the top of the heap. George Delacorte was its editor in chief. They had movie adaptation contracts as well as a contract with the Disney studios. In the 1940s, anything Disney was golden. You knew that you’d be getting a quality product because it had the Disney name on it. “Donald Duck,” “Mickey Mouse,” and “Goofy” comics routinely sold three to five million copies a month.

Consequently, they’re not the most valuable books because the odds of them surviving were so much better. If a book had a print run of 500,000 or less with a smaller company, it is one-sixth of the run of the new “Donald Duck.” That means one-sixth of the copies will continue to exist. So the Disney stuff tends to be some of the least rare of the Golden Age books.

Collectors Weekly: Were Golden Age comics mainly based on superheroes?

Theakston: Yes, until 1945. Again, it all had to do with wanting a god or goddess to go fight the war for us. We needed all the strength we could get. The guy who can lift a car over his head? Send him first. Comics were saturated with superheroes during the war. But once it was over and the public’s tastes changed, comics had to follow suit.

The whole new art, Film Noir trend after the war altered people’s viewing habits and tastes. They wanted dark crime dramas, and that eventually developed into horror comics. Once again, these were images Americans had never encountered before—a picture of a guy with his head exploding. Even in the bloodiest Pulps, you never got that. So it was an effort by the comic book companies to survive by producing tougher and tougher material.

Collectors Weekly: Who were some of the other popular superheroes besides Superman?

Theakston: Plastic Man was pretty remarkable. Will Eisner’s The Spirit appeared in comic book format in the Sunday newspapers. Batman and Wonder Woman from D.C., plus Captain America, The Sub-Mariner, and the Human Torch were all very popular characters.

You also had Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr., who was Elvis’ favorite comic book hero. You know the emblem with Elvis’ motto, “Taking Care of Business” with the lightning bolt? Captain Marvel Jr. had a lightning bolt on his chest, plus a little Elvis-like curl of hair in the middle of his forehead. Elvis wore the jumpsuits with the high collar; Captain Marvel Jr. had a high collar. So while Jr. may not be as widely known as Captain Marvel himself, he had a profound effect on Elvis Presley.

A lot of characters like the Shadow, the Lone Ranger, and the Green Hornet were adapted into comic books and did very well because the public already knew who they were. You’d look at a “Hydro Man” comic book, and say, “Who the hell is Hydro Man?” And right next to it would be a “Green Hornet.” So the fact that these characters were known gave them an edge over the more anonymous, new superheroes.

In fact, most superheroes in the ’40s or during the war were very formulaic and forgettable. They all had a gimmick. Take Hawkman: he’s like a hawk. Or The Sandman: he’s got a gas that knocks you out.

Collectors Weekly: Do collectors tend to collect by superhero or publisher?

Theakston: I know guys who collect every title by a specific company because they like the output, the aesthetic, the artists. Timely Comics and Atlas Comics in the ’50s were precursors to Marvel. Their books are highly collectible because they generally featured fairly good writing and art. Some people collect only those. Other people focus on a particular character. I know a couple of people who collect just Sheena or just Blackhawk comics because they like the artist and the character.

Will Eisner’s “The Spirit” (issue #21 from 1950 is seen here) was one of many titles that made the leap from newspapers to comic books.

A lot of people collect artists. You find a favorite artist and attempt to collect all their work, no matter what company they worked for. That’s me and Jack Kirby. He was all over the place. I don’t care what company put it out. I like Jack Kirby’s artwork. I’ll buy it. I have reissued an awful lot of his work in trade paperback to an appreciative audience.

I developed a process called Theakstonization, which extracts the color from a printed comic book page, leaving a black and white plate. It was nearly impossible to get good reproduction on Golden Age comics because they threw away all the proofs, thinking they’d never need them again. This is another reason so little original art exists from the Golden Age. The only examples tend to be the ones that either the artist saved from the garbage or admirers saved.

I figured out how to bleach the colors out of the comic books. I’ve retouched probably 10,000 pages of Golden and Silver Age comic book art in my career, resurrecting it for new audiences that can’t afford it or wouldn’t know where to get it if they could afford it. I purposely pick out bad-grade copies so that I won’t take too much of a loss if I destroy them. I buy cheap copies and don’t regret it.

For example, a comic from 1940 in good condition in which Kirby did just a six-page job might cost $60. So I’ll buy a coverless copy for $10, take the six pages out, bleach them, and put them into a bigger collection.

As an artist myself, I get great enjoyment from the visual way these guys told stories. I’m much less inclined to read a well-written story that is badly drawn. Generally, if they were working with high-caliber artists, they were working with good writers. So the names that I mentioned, some of the bigger names in the ’40s, ’50s, generally had good writing. They were doing it themselves or they were working with some of the best guys in the business. If you were writing for Jack Kirby, you were a good writer.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the rarest Golden Age comics?

Theakston: The most collectible comics from the Golden Age are always issue number one of a title. They were all untested books, and the publishers were not inclined to do a big print run for fear of having them returned. So a comic book might have an initial print run of 250,000. But then if it’s a smash hit like “Captain America,” three years later they’d be doing a million copies an issue. Consequently, “Captain America” #1 is four times harder to find than “Captain America” #4 because the print runs were so low.

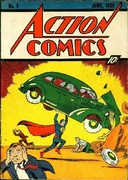

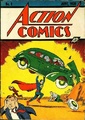

There are also bragging rights about having the first appearance of a character. Batman didn’t appear in “Detective” until #27, but that’s the most valuable book in the “Detective” run because it’s the first appearance of Batman. “Action Comics” #1 features Superman. It’s one of the longest running titles in comics history with probably the most important hero in comics history and his first appearance. That’s probably a six-figure book in excellent condition.

During the war, they only printed 100,000 of a lot of comic books—today, for some of these titles, maybe only six copies are known to exist. If it’s got anything adventurous in it, it’s a rare, valuable book. A famous artist or a character’s first appearance, first issue or not, always adds value to a book.

A number of books are impossible to find, but because of the content and the obscurity of the publishers, they’re not nearly as sought after as something that might be more available and is more appealing in terms of content. But when you get down to less than 10 known existing copies, the book has value no matter what just based on its rarity. It’s the same with coins and stamps. If it’s the only one known, you’re going to get a good price for it.

The factors in pricing and dealing Golden Age comic books are very much like those in pricing cards, coins, and stamps. They have a similar sensibility about what they are, how they’re marketed, and who they’re marketed to. The same factors determine the cost of a comic book as they do in other collectibles. The method for determining the value of a comic book is very simple—scarcity, content, condition.

Of course, the older a comic is, the harder it is to find in good condition. Since the ’80s, with the proliferation of backing boards and comic book bags, mint copies of books from the late ’70s are easy to find because these collectors would go to a store and buy three copies. They read one, put the other two in the plastic bags, and put them in their closet in the cellar and wait for them to accrue value.

So all of these millions of books are sitting as multiple copies in somebody’s house or garage. They’ll never be worth anything. It doesn’t matter what the condition is. There are boxes of them in this condition. There were millions of them printed, and everybody saved them because they thought they’d be worth a lot of money someday. It wasn’t the same with Golden Age comics. People read them and threw them away with no expectation that they’d ever be worth any money.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of your favorites in your collection?

Comics like “The Vault of Horror,” 1951, created a public outcry that led to the Comics Code Authority in 1954.

Theakston: I have a very soft spot for William Gaines’ E.C. Comics because they’re such high quality. He was a very hands-on editor, paid good rates, and attracted the top talent in the business. So anytime you get an E.C. comic, you have a guarantee of at least two good stories out of the three.

I also like anything by Jack Kirby. He rarely lets you down, even though a lot of the books that would be my favorites are out of my price range. I’m kind of partial to the anthology books where you got eight different heroes: “All Winners” from Marvel and Timely, “All Star” from D.C. Comics. If you liked any of the heroes from D.C. Comics, you can pretty much guarantee that they’re showing up in “All Star.”

If you like Superman and Superman is in “All Star,” you might discover Wildcat or Mr. Terrific or any one of the other supporting characters in that book. It’s a good way to cross-populate the characters—Marvel did that a lot in the ’60s. “Spider-Man” consistently had crossovers and guest stars from other titles. So if you never read “Daredevil,” there he was in “Spider-Man.” It was a marketing ploy.

Collectors Weekly: How did the publishing houses compete against each other?

Theakston: By doing their best work, I guess. They all had the same 10 distributors. They all racked in the same amount of space. The only effective way of competing was to produce more comics and push other comics out of the rack. The key was to have the kind of material that the readers liked, to spot the trends.

Collectors Weekly: Are American comics only collected in the U.S.?

Theakston: No. In fact, American comics, at least after the 1950s, were merchandised around the world. I’ve seen Mexican copies of “Superman” from the ’50s. I’ve seen Danish copies of Marvel comics from the ’60s, French copies. They would license the artwork and story, and the publisher in the other country would translate it and reissue it there. Since the ’50s, you could have collected American comics anywhere on the planet. So it wasn’t like all of a sudden American comics are a hot deal because they’re American comics. They were always around. Everything was translated.

Collectors Weekly: What advice do you have for someone new to collecting comics?

Theakston: Go on eBay and start keeping track of which companies produced the most valuable comics. See how they’re sold. See what the sellers have in their advertisements explaining why it’s a valuable book. I’d say learn about the product before you begin investing money. It would be the same thing with any collectible. You really should know the subject inside out before you start throwing money at it. You may end up making some horrendous mistakes.

For someone who collects new comics, I’d say buy what you like because it’s never going to be worth a lot of money. There may be some strange case like “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” where they printed 10,000 the first time out and it exploded. But how rare is that? So I would say buy what appeals to you and enjoy it. Collecting Golden Age books and collecting modern comics are two completely different creatures. There will never be a deficit of these new issues. They’ll always be around, and you could pretty much count on them being in excellent condition because some fanatical collector popped them into a bag with a board on the back.

If you buy what you enjoy, chances are it’ll still be a good read for you 10 years down the line, whether it’s accrued any value or not. You can’t enjoy a Golden Age comic without wearing white gloves and taking care not to breathe on it too hard. They’re very delicate. If you tear the cover, a grading company will reduce the value of the book by $200 and lower it a full grade.

Collectors Weekly: Is comics collecting still as big as it was in the ’60s?

Theakston: I’d say definitely not because of video games, the thousand TV channels, cell phones, iPods, and anything else that divert our attention. When television took hold in the ’60s, people started reading less. Their entertainment was much more passive; they could just sit there and let it flow over them. In that respect, television has been the undoing of the comic book. Comics are going through a very difficult time right now because so many of the outlets have dried up—they stopped selling comic books at 7-Eleven, which must have been a terrible blow to the business.

The whole hobby has changed radically since I started collecting. The Golden Age books that were perceived as rare were expensive but still doable. Now, it’s a huge business, people expect to make money, and prices go accordingly. You have a situation where people who were collecting comics in the ’60s, especially the early 1960s, are now in their 50s. In a lot of cases they have a lot of money, discretionary funds. And they compete against each other and drive the prices up.

What’s the true value of a book? Well, only as high as what people are willing to pay for it. There may be only five people in the United States who’ll pay X amount of dollars for X book, but it doesn’t matter. If those five people will pay that kind of money, everybody else is locked out. There might be another 200 people willing to spend half that amount, but they’ll never see it because the big rollers are controlling the market in that respect. Maybe 50 dealers in the United States control probably 90 percent of the Golden Age stock.

I think the only way comics are going to succeed in the future is over the Internet and in major bookstores because the old outlets are drying up. If Diamond Distribution, the largest distributor of comics in America, went out of business, it would mean the end of the comic book business as we know it. The industry has painted itself into a corner by relying on one key distributor.

That’s one of the main reasons why comic book companies publish collections. A 12-issue mini series bound into a single volume can be sold in a bookstore. They get two sales off of it from the initial comic book fan, and then the casual reader at Barnes & Noble, or wherever, discovers it. That’s probably the future of comics. It’s a very good sign that major book retailers now have entire sections devoted to comic books. That’s a positive sign in a drastically shrinking industry.

Today, comic books are largely jumping-off points for Hollywood. If you can get your creation into a comic book, then you can send it to a film company and say, “Are you interested in this property? Here it is visualized, fully realized.” Right now there are more than 100 comic-book-adaptation movies in production, which shows you where all the true creativity of popular culture rests these days.

(All images in this article courtesy the Grand Comic Database)

Vintage 1970s Lunch Boxes Revisited: When Pop Culture Ruled the Playground

Vintage 1970s Lunch Boxes Revisited: When Pop Culture Ruled the Playground

When Superheroes Took Over Comic Books

When Superheroes Took Over Comic Books Vintage 1970s Lunch Boxes Revisited: When Pop Culture Ruled the Playground

Vintage 1970s Lunch Boxes Revisited: When Pop Culture Ruled the Playground Toys That Were Made to Be Broken

Toys That Were Made to Be Broken Golden Age Comic BooksIn 1938, “Action Comics” #1 changed the course of print entertainment when …

Golden Age Comic BooksIn 1938, “Action Comics” #1 changed the course of print entertainment when … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Golden Age Collecting was extremely popular in Chiago i nthe early and mid 1060’s among what little tht existed of “organized” fandom (there were maybe 100 collectors who interacted with each other occasionally)through loose networks aminly o nthe North side. The actio nwas all through a number of skid row bookstores. Around 1965 silver age comcis start going up in price from the stanard dime t oa dollar or two but many GHolde nage comcis were avaialble from the same outslets for a couple of bucks especially second string titles

So if you were a kid and could cover your dime buys at the newstand and have a dolalr over you could add a Golden Age title if your family let you go to skid row- a lot of colelctiosn were built that way. I can rememebr buying Boy COmmnados for 50 cent each All mericans for $2 Headache was I had very little cash so we are talking one or two comcis every 2-3 weeks when my fatehr had to work on saturdays downtown. As silver age books became more valauble a lot of us cash in our early FF and Hulks for either cash to go to collegee or traded them to teh bookstores for Golden Age

A while different world

The “Pure Imagination” pages are a vivid tour through the best classic Super Hero and Adventure comics of ALL time. For kids and adults back in the 1950s-1970s, the art design, color, action and stories found in typical comic books were the stuff fantasy and dreams are made of. Wonderful!!!! :-)

Hi!

I juat saw your stuff here on the Net. Perhaps you can help me with something?

I am 59 and still rememeber buying & collecting Superman Comics. I am trying to locate the Issue Numbers for the following articles or related subjects pertaining to Superman:

Superman Visits Earth II

Superman Visits Planet TERRA

Enlargement of City of Kandor

Creation of Bizzaro

Tales of the City of Kandor

I am wondering if DC Comics produces some kind of an Article Index or Archive so if you are lookign for a particular issue covering a certian subject, you might be able to reference this Index in order to locate it?

Darryl,

Go to the Grand Comic Database and search Superman and Action Comics. Go to the cover reproduction pages, make a list and hit eBay.

came across a supermen of america membership packet.belonged to my father,original envelope with 1/2 cent postage and it includes certificate,along with the decoder.i was wondering how rare this is,and what it may be worth. It is dated 1943,in mint condition.Thank you for your help in this matter.

Not really my strong suit, but I’m guessing $500 to $1,500. There is a premiums price guide, and I suggest that you get that before considering selling your items.

GT

i would like to know what dc the phantom comics are worth,also the invaders comics, and the captain universe comics?

Love comic book’s This is a slam Pow Hit for me.Well done indeed.Frosty21

I like your comments regarding the plastic slabs and the investment mentality. I have bought a few golden age DC titles that were graded and slabbed, and I decided to break them open. (Just take the claw of a hammer to the part that extends past the comic). Some people might think that foolish, but I say if you can’t just enjoy it for what it is, then it isn’t really worth owning.