It’s perhaps fitting that the man recognized as the father of the video game, that quintessential American invention, was a refugee from Hitler’s Germany, whose personal story converged with America’s at a critical time in the nation’s history.

“I had the misfortune of being born in a horrendous situation,” Ralph Baer told the Computer History Museum, of his birth to Jewish parents in 1922 in southwestern Germany. When the Nazis came to power, Baer was still a young child. They threw all Jewish students out of school, forcing him to seek employment at the age of 14. He worked as an office typist, then collected money for bars, and took a menial job in a shoe factory, among other jobs. According to a story his son Mark had heard, which he passed on to me, Baer’s boss at the shoe factory told him he would never amount to anything. Undaunted, the young Baer showed up his boss by inventing a machine that automated what had been a one-off hand-punch process, an early sign of his innovative talent, not to mention his defiance.

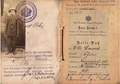

A quick learner, Baer began a lifelong process of self-education. He taught himself English, which he said proved critical in getting his family on the “miniscule” list of individuals accepted by U.S. immigration. Just weeks before Kristallnacht, the “Night of the Broken Glass,” which signaled a major escalation of the Nazi state’s war on Judaism, the Baer family escaped Hitler’s grip. They made their way to New York, where Baer’s mother had relatives. In retrospect, horrifying as they were, Baer’s early years in Germany sharpened personality traits that helped prepare him for a career in innovation: perseverance, scrappiness, risk-taking, resourcefulness, and self-confidence.

Baer was only 16 when he arrived in New York in 1938. He immediately showed a characteristic immigrant’s work ethic and drive to succeed. Resuming his self-education—necessary because of his lack of any school degree from Germany—he spent afternoons studying at the New York Public Library. He also took correspondence courses in radio and television electronics. In 1943, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and then assigned to military intelligence on account of his fluent German and other language skills. After the war, like millions of veterans, Baer went to school on the GI Bill. He had to go to Chicago for schooling because all the colleges in New York were completely full of returning GIs. In some ways, that was a blessing as he met radio and television pioneers there and earned what he believed was the first B.S. degree anywhere in television engineering. Thereafter, he returned to New York.

Army days, Tidworth, England, 1944. Courtesy of Ralph Baer and Bob Pelovitz.

Innovation requires the good fortune to be at the right place at the right time, as much as it does individual genius. Baer came to the United States during the heyday of the American industrial research lab, and New York was a center of electronics innovation. It was a world that seemed made for him. Intelligent and ambitious, he quickly found employment in the growing defense electronics sector in New York City, including at such companies as Loral Electronics and Transitron.

While he did well at jobs that capitalized on his military experience and knowledge of electronics, Baer kept an eye on the extraordinary things happening with commercial radio and TV. In America’s postwar economic boom, televisions were entering homes at an amazing rate. There would soon be more than 50 million TV sets in American living rooms, and in this, Baer saw a rare opportunity.

One of his first assignments at Loral Electronics was to build a television set. While doing this, he became convinced TVs were underutilized as a one-way, passive medium. Thus was born his idea of interactive TV, and what he initially called “participatory television.” “When I was with Loral,” he recalled, “I suggested that we do something drastically different with a TV set. But the chief engineer said, ‘Forget it. You’re already behind schedule anyway, so stop screwing around with this stuff. Build the set.’”

Baer finally had a chance to realize his dream a few years later at his job at Sanders Associates, a defense electronics firm in Nashua, New Hampshire. Rising quickly in the organization, Baer showed he knew how to operate within a large corporate R&D structure, but soon proved his imagination could not be contained by that or, for that matter, any structure.

“What distinguished Baer from many other inventors was his attention to commercialization.”

Baer was having trouble creating a device that would actually introduce images on the TV screen until he had a eureka moment while on a business trip to New York City. Sitting at a bus stop, he realized he could build a small radio-frequency signal device, “so you could get into the antenna terminals of a TV set on Channel 3 or Channel 4.” He realized that this was a way to begin to make the television set more interactive.

Soon after, while managing a military research lab of hundreds of technicians and engineers, Baer quietly commandeered a small former library space on the fifth floor of the company’s Canal Street building, where he secretly started what he called his own “skunk works.” When the pace of business allowed, he and a couple of tech designers he had selected to assist him worked sporadically on the idea of a game console that could work on unmodified TV sets. He also did some related work in his basement lab in his home. “Little by little, we got stuff on the screen,” he remembered. “Then we started thinking about what games to play.” That included the first-ever onscreen ping-pong game.

Out of this original idea came his famous prototype “brown box,” a single console containing the first video gaming system, now in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Once Baer created a prototype, he finally went public. Baer presented it to his managers, persuading them they could make money with TV/video games, even though such games had nothing to do with the serious business of radar and other defense R&D that were Sanders’ main product lines.

And make money they did. Sanders, which had obtained clean and clear property rights to Baer’s prototype for the princely sum of one dollar, licensed the brown box technology to a TV company, Magnavox, which produced the hugely popular Odyssey video game console. Sanders ultimately earned roughly $100 million (1970s dollars) from the patents Baer assigned to the company. What distinguished Baer from many other inventors was his attention to commercialization: He knew an invention didn’t count unless it actually found a market. When he was later asked how he managed to develop commercially successful home video games at a military contractor that had nothing to do with television, he quipped it was “a piece of Jewish chutzpah.”

Baer playing a videogame he invented; his basement workshop is in the background. Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Baer had always been a tinkerer at home, too, and his success with the brown box only motivated him to do more. He was clearly happiest working in his cozy basement in Manchester, New Hampshire, 18 miles away from Sanders, amid family and his favorite tools and devices. West Coast garages rank high in the hierarchy of temples of innovation—both Hewlett Packard and Apple famously trace their origins back to suburban garages. But if you’re into video games, you owe a debt of gratitude to an East Coast basement. At the National Museum of American History, we’ve reassembled that very lab as a key exhibit in the new wing dedicated to innovation and American enterprise.

Experts often debate whether invention and innovation rely more on solitary endeavors or institutional collaboration, but Baer’s work shows that it’s more often than not a combination of both dynamics that spark technological revolution, as he straddled both models with his twin workplaces. Sanders provided resources and an “ecosystem” for innovation. His Manchester basement with its bright red door provided an all-hours escape and unfettered freedom. Baer’s personal odyssey has become part of our common American story, and I am proud that his basement workshop has been enshrined for future generations of video game enthusiasts.

(Arthur Molella is director emeritus of the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center at the National Museum of American History. Molella was part of the curatorial team that brought Ralph Baer’s workshop to the museum. This story was written for What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square. It was originally published on December 11, 2015. Primary editor: Andrés Martinez. Secondary editor: Jia-Rui Cook. Lead photo courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Interior photos courtesy of Ralph Baer, Bob Pelovitz, and Smithsonian Museum of American History.)

Let There Be Light Bulbs: How Incandescents Became the Icons of Innovation

Let There Be Light Bulbs: How Incandescents Became the Icons of Innovation

The Politics of Prejudice: How Passports Rubber-Stamp Our Indifference to Refugees

The Politics of Prejudice: How Passports Rubber-Stamp Our Indifference to Refugees Let There Be Light Bulbs: How Incandescents Became the Icons of Innovation

Let There Be Light Bulbs: How Incandescents Became the Icons of Innovation Could an Old-School Tube Amp Make the Music You Love Sound Better?

Could an Old-School Tube Amp Make the Music You Love Sound Better? TelevisionsThe basic technology for electronic television (as opposed to earlier mecha…

TelevisionsThe basic technology for electronic television (as opposed to earlier mecha… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I can’t wait to see his workshop at NMAH. Nicely written.

For anyone who wants to learn even more about Ralph Baer, his professional papers are housed at The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY.

I have learned something new today. Thank you for this insightful article. Very inspiring and motivating. I hope to revisit the Smithsonian to check out the exhibit and would love to review the papers mentioned by Julia in the comments section. Very cool. Cheers! ☕️