At a time when obscure new whiskeys are appearing on cocktail menus from Savannah to Seattle, it’s hard to imagine the American whiskey industry was ever under threat. For starters, the grain-based spirit is as American as apple pie, or at least George Washington—in fact, the first president’s Mount Vernon estate was once the site of the country’s largest distillery, specializing in the Mid-Atlantic region’s famous rye whiskey. But despite its noble foundations, America’s whiskey industry suffered repeated setbacks, like our 13-year Prohibition on alcohol, which nearly drove it to extinction.

“Patients with a prescription could go to a pharmacy and get a pint.”

In the early 20th century, some distillers survived attacks from anti-alcohol prohibitionists by promoting the drink as an important medicine, creating a legal marketplace similar to medical marijuana today. But even after 1933, when the public got fed up with Prohibition’s silly charade, the massive diversion of resources toward World War II coupled with customers’ changing tastes in alcohol delivered further blows to whiskey distilleries, leaving the industry grasping at straws throughout the 1980s and ’90s.

Noah Rothbaum chronicled the industry’s bumpy past, along with the eye-catching packaging of each era, in his new book, The Art of American Whiskey. “Throughout the history of American whiskey, you see these repeated starts and stops,” says Rothbaum, “which allowed for other types of alcohol to gain a foothold here. It’s amazing that we have a strong American whiskey industry after all of these ups and downs.”

Today, whiskey is clearly in the throes of a comeback, as big players like Jack Daniel’s and Jim Beam offer single-barrel whiskeys aimed at connoisseurs and new distilleries seem to multiply by the month. We recently spoke with Rothbaum about how the industry has weathered its highs and lows, allowing for the triumphant return of fine whiskey to bars across America.

Top: A selection of American whiskeys from the early 20th century. Photo courtesy Finest & Rarest. Above: Before glass bottling was affordable, distilleries used ceramic vessels like these George Dickel jugs, circa 1900. Photo from “The Art of American Whiskey,” courtesy of Diageo.

Collectors Weekly: How did whiskey get its start in the United States?

Rothbaum: People have been making whiskey in America since before it was a country. Traditionally, people in the Northeast or the Mid-Atlantic states made rye whiskey, and those in Kentucky and some of the other Southern states made what would become known as bourbon. There were many distilleries founded in the beginning of this country, but most were run by people who had a small still on their farm and used it as a good way to turn their excess crop into something that was more shelf stable, durable, and valuable.

For a long time, if you wanted to buy whiskey, you weren’t buying bottles. When you’d go to a liquor store or grocery store, you’d fill up your own jug or flask or decanter. Bars and grocery stores would purchase a barrel of whiskey, and then they would sell that by the glass, or they’d allow people to fill up their own containers. Nothing really came in a glass bottle because it was so expensive to make them at that time.

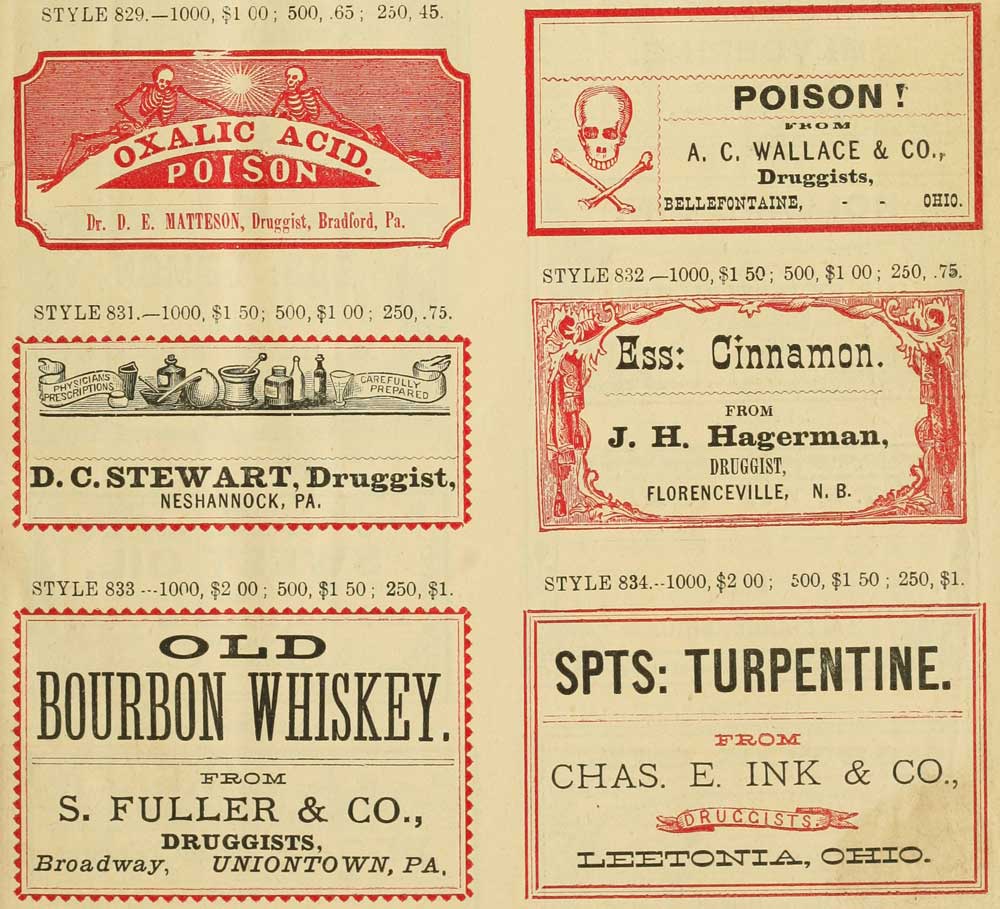

This catalog page of apothecary labels from the late 19th century shows that whiskey was sold as medicine even before Prohibition.

That really changed in 1870, when the first bottled American whiskey came out. It was called Old Forester, and it’s still available today. Old Forester was marketed not at consumers, but at doctors, since they would prescribe whiskey for a range of maladies. Previously, doctors couldn’t be sure of how pure their whiskey was because there were all types of middlemen between the distiller and the final customer, or the patient in this case. Because Old Forester was sold in a bottle, you could guarantee that it was pure unadulterated whiskey, meaning it wouldn’t do more harm than good.

Around the turn of the century, a machine was invented that made bottles very cheaply and effectively, so you had a glass-bottle revolution as more spirits and other products were starting to be sold in bottles. That kicked off a real boom, not only in American whiskey production, but also whiskey advertising and marketing, because for the first time people actually had a choice of what they drank. Previously, they didn’t have many options—each bar or store would have a limited number of casks. E. H. Taylor stood out as a pioneer, putting shiny brass bands around his casks so buyers would know it was his whiskey.

After Congress passed the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, bonded distilleries often used Uncle Sam in their advertising to reinforce the superiority of their alcohol.

Collectors Weekly: How did the distinction between bourbon and rye whiskeys develop?

Rothbaum: It was mostly geographic, based on what would grow in different regions. Around the world, people made alcohol from whatever was available—if you had grapes, you would make wine; if you had apples, you’d make applejack or calvados; if you had potatoes, you’d make vodka.

Bourbon has to be at least 51 percent corn, and then usually it’s a little bit of malted barley and some rye, though there are a few brands like Maker’s Mark or Weller that use wheat instead of rye. Bourbon also has to be aged in a new oak container. Rye whiskey has to be made predominately from rye, but it can be up to 100 percent rye. That’s the main difference between the two—the mash bill or recipe for rye is mostly rye, and for bourbon, it’s mostly corn.

A Pennsylvania label for corn whiskey, now known as bourbon, circa 1910s. Image courtesy Saint Mary’s Antiques.

Rye is a hearty grain, so it can survive the winter and be harvested a couple of times per year. It’s a nice cover crop, and it’s indigenous to the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic area, whereas corn is something that grows very well in the South.

You have to remember that back in the day, people weren’t aging their whiskeys for 8, 10, 12, 20 years. If you go back to someone like George Washington, who had the largest rye distillery in the country at Mount Vernon at the end of the 1700s, his whiskey was made to be drunk immediately. It wasn’t going to be aged; it would have been drunk as a clear alcohol.

The distinctions we make today are for products that are quite different than what people were drinking back then. By the beginning of the 20th century, things had become much more standardized. Glass bottles, combined with a number of government acts that went into effect, helped ensure what was in the bottle was safe to drink and actually as advertised. Today, if you make bourbon, you have to use a new oak barrel that has been charred inside. The barrel provides all the color of the whiskey and a lot of the flavor.

Before Prohibition, rye grew at least as far west as Stratton, Colorado, as shown in this 1915 photo.

Collectors Weekly: What’s the difference for drinkers?

Rothbaum: It’s not one of these fine distinctions; it’s one that anybody can discern. Rye by nature is a lot spicier. It’s sort of like the difference between eating rye bread and cornbread. Corn creates a sweeter whiskey, while rye has that big, spicy, bold flavor. Some bourbons will have a little spicy kick, and it’s because they also contain rye.

Often, what you’ll see is people start out drinking a wheated bourbon, which is the sweetest version, like Maker’s Mark. Then, as they drink a little more and develop an appreciation for whiskey, they’ll often move to a high-rye bourbon, more like Wild Turkey. And then finally, they move to a straight rye whiskey.

Keep in mind that rye whiskey, compared to bourbon, is a tiny category that we almost lost entirely. By the 1980s, all of the distilleries in the Mid-Atlantic states, which were famous for making rye, had gone out of business for good. Many of these brands’ intellectual property was bought up by bourbon producers, which is why Rittenhouse and Pikesville ryes are produced by Heaven Hill in Kentucky. Even a company like Heaven Hill, which makes some of the best rye whiskeys on the market, was only making it one day a year, which was more than enough to meet demand. They say they spill more bourbon on the floor in a year than they make rye whiskey.

This bottle of Four Roses from 1924 includes a full prescription from a drugstore in Sparks, Nevada. Photo from “The Art of American Whiskey,” courtesy of Four Roses.

Collectors Weekly: Why were some distilleries allowed to keep selling whiskey during Prohibition?

Rothbaum: In 1920, it became illegal to manufacture, transport, or sell hard alcohol in America, but the government gave six companies a license to sell bottled medicinal whiskey because doctors and dentists were still prescribing alcohol for their patients. They needed a way to continue to do that, so a few companies were allowed to bottle medicinal whiskey from their previous surplus, and patients with a prescription could go to a pharmacy and get a pint.

During Prohibition, O. F. C. packaged its bottles into boxes that included an endorsement from “leading chemists” of the time. Photo from “The Art of American Whiskey,” courtesy of Buffalo Trace Distillery. (Click to enlarge)

There’s an amazing image in my book of a bottle of Four Roses that has a label on it from a pharmacy in Sparks, Nevada, and it tells the patient exactly how they were supposed to drink it, like any other kind of medicine would have directions for how to take it. With the Four Roses bottle, the patient was being instructed to mix the whiskey with hot water, which is essentially a Hot Toddy.

I had known medicinal whiskeys were available at this time, but I assumed they came in nondescript bottles, like rubbing alcohol or aspirin. But of course, they didn’t. They were packaged in these beautiful, engaging, and highly illustrated boxes and bottles, which shows that, in fact, the whole medicinal whiskey business was not about “medicine” but about letting people continue to drink whiskey.

Before Prohibition, whiskey was prescribed for a range of real symptoms and illnesses, but after alcohol was outlawed, I think it was prescribed for things like the common cold or stress or anxiety as a way to get around the law. I imagine a lot of prescriptions were for subjective conditions. I think it’s an accurate parallel to some of the marijuana clinics today, with prescriptions ranging from the legitimate to the recreational.

Obviously, these companies were still trying to sell and market their products during Prohibition, and the ones that survived had to demonstrate they already had large supplies of whiskey already on hand since they weren’t allowed to make new whiskey. You also had a lot of consolidation, as companies that were allowed to bottle medicinal whiskey ran low on stock and acquired companies that hadn’t been permitted to bottle it. The government also eventually declared a distiller’s holiday because they ran out of medicinal stock, and this allowed them to make more. It shows how much of this “medicine” was actually being sold.

Collectors Weekly: What kinds of whiskey were available right after Prohibition?

Rothbaum: One of the rabbit holes I went down was researching the day that Prohibition ended, December 5, 1933: Where did the alcohol people celebrated with come from? How did they get it? I found this “New York Times” article where they sent a reporter around the city checking to see who had alcohol and who didn’t. One of the bars bought its alcohol from what they called a “reputable speakeasy,” because basically overnight, the whole allure of speakeasies was gone. There was a whole generation of people who’d never been able to drink in public, and all these once-popular spots were suddenly empty—their cachet was gone. What was novel was being able to go into a bar, order a drink, and enjoy it without fear of arrest.

This National Distillers ad from 1934 plays up the rarity of aged whiskey that survived the entirety of Prohibition, though it likely didn’t taste great. Image via Whiskey Bent. (Click to enlarge)

Canadian whiskey flooded the market, since they had still been producing during American Prohibition. You also had cruise ships bringing alcohol over from Europe, and things like rum and tequila started to come on the market.

It was a difficult period for the American whiskey industry because most of the distilleries had to be completely rebuilt. They had sat empty or been stripped of anything that people could sell or salvage. What was left was some very old whiskey, like 17-year old whiskeys, which would have been super woody. We’re not talking about a fine old bourbon that’s been carefully monitored and fussed over like today, but ones that had sat in a warehouse and accidentally managed to survive. It was very hard to start up again, and many companies never did, though a few big businesses like Schenley bought up these defunct brands.

There were also a number of new companies starting up, including Heaven Hill, but just like today, if you’re opening a craft distillery, it’s difficult to get a loan from a bank. To raise funds, either you needed your own capital, or you needed friends, family, and private investors with money. Banks were leery of loaning money to distilleries because the illicit associations with Prohibition lingered for so long. The unsavory, criminal element of selling alcohol during that time really colored people’s perceptions of the industry for decades.

This 1934 ad reminded consumers that Four Roses was blended and aged, unlike “green whiskey,” and sealed in a tamper-free bottle. Photo from “The Art of American Whiskey,” courtesy of Four Roses.

Collectors Weekly: What was the impact of World War II on whiskey production?

This 1950 ad for Old Schenley emphasizes the difficulty of aging quality whiskey following Prohibition.

Rothbaum: Just as American distilleries started to get back into the swing of producing alcohol, World War II hit, and they all switched to making goods for the war effort. Most of them were making high-proof alcohol that could be used as a base for things like explosives, rubber, and antifreeze.

It wasn’t until the early ’50s that we had a constant supply of American whiskey again. Even before World War II was over, Winston Churchill made some grains available to the Scotch whisky industry because he knew how important it would be after the war. In contrast, after the war, Truman temporarily halted production at American distilleries in order to bring food relief to our allies in Europe.

Rye whiskey distilleries had a very hard time getting back into production after being essentially closed starting with Prohibition in 1920. A lot of the farms in the Mid-Atlantic states were replaced with housing developments, so most of the rye disappeared. You also had returning GIs who were exposed to smoother Canadian and Scotch whiskey during the war and came home wanting this different taste.

By the 1950s, people’s attitudes had changed: They wanted smoother drinks, so they were drinking a lot of blended whiskeys, highballs, and mixing whiskey with club soda or ginger ale. Blending whiskey was an attempt to meet demand, and the typical proof came down from 100 to 86 or so. By the ’50s, distilleries still hadn’t produced much straight or “bonded” whiskey. Bonded whiskey had to be 100 proof, the product of a single distillery, and stored in a bonded warehouse. All those bonded rules are still in effect today.

There are several types of blended whiskeys, but in America, it’s a mix of straight whiskey and neutral grain spirit, and the marriage of these flavors often makes it smoother. Most whiskey we’re drinking today is straight whiskey.

Following World War II, American drinkers turned to blends and lower-proof spirits for their cocktails, as seen in this Jim Beam Manhattan ad from 1969. Photo from “The Art of American Whiskey,” courtesy of Beam Suntory Inc.

Collectors Weekly: How did federal law finally shift to benefit the industry?

Rothbaum: The big change happened because of the Korean War. Lewis Rosenstiel of Schenley Industries made a bet that, just as in World War II, the Korean war would be prolonged and distilleries would shut down to make goods for the war, so he increased production to stockpile extra whiskey. Then, of course, the Korean War wasn’t prolonged and distilleries weren’t shut down, so he suddenly found himself with a giant amount of whiskey soon to become “mature” in the eyes of the federal government, and he was going to have to pay taxes on all of it.

Through intense lobbying, Rosenstiel was able to get the government to change their definition of mature whiskey from 8 years to 20, which was retroactive, meaning it covered all the whiskey in his warehouses. This allowed Schenley to save a ton of money and also opened the door for distilleries to produce older whiskeys. Schenley later ran ad campaigns touting the benefits of older whiskey because they now had plenty of it.

The 1970s saw a proliferation of lighter whiskeys, as seen in this Galaxy Whiskey ad from 1972, but it wasn’t the spirit’s finest decade.

Collectors Weekly: Why did whiskey fall out of favor again in the 1970s?

Rothbaum: In the 1950s and ’60s, distillers finally experienced an uninterrupted period of production, plus Americans had money and wanted to drink good quality straight spirits. But at the same time, by the end of the 1960s, the country saw so many social upheavals and divisions between generations—from the Civil Rights movement to the War in Vietnam to women’s rights—that you had a real divide between older and younger generations. And young people didn’t want to drink like their parents or grandparents.

Bay Area-based St. George Spirits created this single malt whiskey in 1996 with a label designed by artist David Lance Goines.

I don’t think it’s any coincidence that during the ’70s, you had the “Judgment of Paris,” when for the first time ever, American wines defeated French wines in a blind taste test. You also had the start of the craft beer movement in America with entrepreneur Fritz Maytag buying and popularizing Anchor Steam Brewery in San Francisco.

By the end of the decade, vodka was becoming more popular with young people than whiskey. What really put vodka over the top was the Swedish brand Absolut, which used an ad campaign featuring Andy Warhol’s art and made it trendy to be drinking vodka for the first time. Not only is vodka clear while whiskey is dark, but vodka by law is also tasteless and odorless. It’s a neutral spirit, whereas whiskey is touted for its flavor.

In the 1950s, vodka made up a very small percentage of sales. But today, it’s more than a third of all liquor sales. The rise of vodka is unbelievable. There was a great decline in American whiskey sales beginning in the ’70s, and it wasn’t until the late ‘90s and early 2000s that the industry’s rebirth really begins in earnest.

Collectors Weekly: How did the American whiskey industry stage its most recent comeback?

Rothbaum: In many ways, American whiskey distilleries saw what the Scotch companies had already started doing and borrowed a page from their playbook. They began introducing small-batch, single-barrel products, higher-end and limited-edition whiskeys, and experimenting with all types of new stuff. With the rise of artisanal wine and food movements, people were starting to get interested in where their food and drink comes from. It was a perfect storm. All of these things came together to help create this new golden age for American whiskey.

(Images reprinted with permission from “The Art of American Whiskey” by Noah Rothbaum, copyright 2015. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.)

My Goodness! Guinness Collectors Snap Up Secret Stash of Unpublished Advertising Art

My Goodness! Guinness Collectors Snap Up Secret Stash of Unpublished Advertising Art

Medicinal Soft Drinks and Coca-Cola Fiends: The Toxic History of Soda Pop

Medicinal Soft Drinks and Coca-Cola Fiends: The Toxic History of Soda Pop My Goodness! Guinness Collectors Snap Up Secret Stash of Unpublished Advertising Art

My Goodness! Guinness Collectors Snap Up Secret Stash of Unpublished Advertising Art How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict

How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict Liquor BottlesThere are as many styles of antique liquor and spirits bottles as there are…

Liquor BottlesThere are as many styles of antique liquor and spirits bottles as there are… FlasksWhile flasks have had a variety of uses over the years, such as the storing…

FlasksWhile flasks have had a variety of uses over the years, such as the storing… Whiskey BottlesStrictly speaking, there’s no such thing as a "whiskey" bottle in Scotland.…

Whiskey BottlesStrictly speaking, there’s no such thing as a "whiskey" bottle in Scotland.… AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci…

AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article, Hunter. As a whiskey enthusiast myself, I found this very informative.

It’s great i like the Wisky Cocktail.

but it’s hard to imagine the American whiskey industry was ever under threat

Informative and interesting one, i liked it.

Extremely informative; one might say, “Intoxicating”.

I love whiskey and bourbon, but don’t understand this nationwide move towards rye-based spirits. It’s a fad to me and you’re uncool if you don’t appreciate the “spice” of rye. As someone who enjoys “drinking what they like”, I’ll share the rye I have for Manhattans with friends and the near consensus is “Jesus, this is spicy!”

I don’t discriminate when it comes to liquor (Pinhook being my favorite bourbon on the market) but I hope the rye fad doesn’t lead to a quality drop in other spirits.

“You also had cruise ships bringing alcohol over from Europe… ” I doubt that they were cruise ships. Those ships were probably what were called ocean liners–ships meant for transportation across open oceans. Cruise travel didn’t become popular until the 1970s.

Great read! Love learning about the history of typical items or ingredients. Regarding whiskey, I still don’t get why Fireball has suddenly become so popular. Here’s my take on it: http://digthisdesign.net/diy-design/recipes/diy-fireball/

Nice article. Nice accompanying photos, too. Particularly liked the 1934 Four Roses ad, showing a stamped metal shot glass screwed onto special threads on the bottle neck. (I assume there’s a stopper underneath.) V-e-r-y custom packaging, for whiskey drinkers on the go!

I have glass/crystal bottle of wiskey (no wiskey in it just the bottle) from Ireland and has GC on the underside of it is this valuable? Hope you can help look forward to hearing from you Meredith