Like a lot of people of a certain age, I’ll never forget the night I watched The Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” It was February 9, 1964, I was 7 years old, and John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr had just invaded America. Coming scant months after the assassination of President Kennedy, the whole country (or at least 73 million television viewers) was ready for an evening of guilt-free fun.

“I used to watch them wiggle their butts on stage.”

Even more memorable was an afternoon a couple of years later, a day or two before August 29, 1966, when The Beatles were scheduled to play Candlestick Park, then the home of Willie Mays and the San Francisco Giants. My friend Billy had offered me a ticket to the show, as well as a ride with his big brother. It was a done deal, all I had to do was say yes.

“No thanks,” I replied instead, with all the breezy hubris of your typical 10-year-old. “I’m into the Stones.”

We didn’t know it at the time, but that concert at Candlestick would be The Beatles’ last. Apparently, a lot of other people didn’t know it either: The show was not even close to sold-out.

Above: Female fans at Shea Stadium in New York, August 15, 1965. Photo: Robert Whitaker. Top: The Beatles played the Cow Palace in San Francisco on their 1964 North American tour. Photo: Mirrorpix.

With the golden anniversary of the Fab Four’s first visit to North America upon us, many are thinking about their half-century relationship with The Beatles, whether it’s the first time they heard “Tomorrow Never Knows,” that late night in their dorm room when they realized that Paul McCartney was singing the words “the doctor came in, stinking of gin” in “Rocky Raccoon,” or, as in my case, the fateful afternoon they decided not to see the band for free because of musical principles that now seem indefensible.

“John Lennon himself rebuffed Finley, saying, ‘Chuck, we only do 11. That’s it.'”

This month, a two-volume chronicle of The Beatles’ official tours in 1964, ’65, and ’66 called “Some Fun Tonight: The Backstage Story of How The Beatles Rocked America: The Historic Tours of 1964-1966” takes a behind-the-scenes look at Beatlemania back in the U.S. of A. The 618-page, hardbound boxed set, written by Chuck Gunderson and retailing for $175 (including postage in North America), tells the real story of what those tours were like in the words of the DJs, promoters, and people who were there, brought to life via some 450 photographs of the band performing their 11-song sets, giving increasingly impatient press conferences, and fleeing the affections of their frenzied fans.

Gunderson, who’s been working on the book for roughly eight years, had a harder time than he expected finding images to go with every city on each of the three tours. “One of the things that surprised me was how little photographic evidence exists of these tours,” he says. “You would think that with their international superstardom in ’65 and ’66, there’d be photos galore. But a lot of photographs had been stolen over the years out of newspaper archives. In the process of writing this book, we were actually able to save 54 negatives from the last show at Candlestick Park that were about to go on the black market. About seven or eight of them are now presented in the book and all are safely archived.”

Tickets for Beatles shows in 1964 at the Hollywood Bowl and 1965 at Shea Stadium.

Getting the stories right was often just as challenging. “It was endless phone calls and emails,” Gunderson says, “not just to get a story, but also to corroborate it, to make sure the stories matched up. I didn’t want the book to just be a bunch of facts and figures thrown around. I’m a trained historian, with a master’s in history from the University of San Diego. To do it right, you have to confirm sources and things like that. It took a lot of perseverance.”

By design, Gunderson skipped the February 1964 visit, which included three appearances on “Ed Sullivan,” plus a gig in Washington, D.C., and another at New York’s Carnegie Hall, deciding instead to focus on the official tours. “Bruce Spizer covered that extremely well in his book, ‘The Beatles Are Coming,’” Gunderson says. “I didn’t want to re-create his well-crafted history, so I decided to stick with the three tours.”

Within that structure, Gunderson treated each city like its own chapter. “I decided to basically write the history of the moment they arrived and the moment they left, as well as all the negotiations that went on beforehand. Along with the photos, I wanted to present the memorabilia from each city, so the book has tickets, handbills, contracts, newspaper ads, programs, and anything that was sold at a concert. Each city gets its own comprehensive history.”

A press conference in Boston, September 12, 1964. Photo: Kevin Cole.

The first city profiled in the book, San Francisco, is also the last. Purely by coincidence, San Francisco was the first stop of the first Beatles tour in August of 1964, as well as the place where the tour ended in 1966. “The Beatles were going to kick off their tour in San Diego, California, on August 18,” Gunderson says, “but because of contractual commitments they had in the U.K., they were not able to do it. So the first show ended up being on August 19 in San Francisco at the Cow Palace. When you look at that ’64 tour,” he adds, “it’s really haphazard. They’re north, they’re south, they’re back east. It was not a logical procession across the United States. They were just all over the place.”

In fact, on that first U.S. tour, which included three shows in Canada, one date was even added along the way. “Kansas City was not on the original itinerary,” Gunderson says. “The tour had already been scheduled and booked. September 17 was supposed to be a day off for the Beatles. They were going to play New Orleans on the 16th, and then they had hoped to explore New Orleans a little bit, which, obviously, they couldn’t have done anyway, given all the fans.”

But Charlie Finley, who owned the Kansas City Athletics baseball team, had promised his city a Beatles concert, so he started working on the band’s manager, Brian Epstein, from the moment the tour began in San Francisco. Finley was prepared to pay top dollar to bring The Beatles to Kansas City, which is saying a lot, since they were already the best-paid act in show business.

Gunderson’s book features images of behind-the-scenes memorabilia, such as this press pass issued to disc jockey Ken Douglas of Louisville, Kentucky, radio station WKLO.

“At that time,” says Gunderson, “the big stars were Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland, who were each getting between $10,000 and $15,000 a show. When The Beatles came around in 1964, Brian was getting them anywhere from $20,000 to $40,000 per show. Finley offered $100,000, and Epstein essentially said, ‘No. They’re having a day off; the tour is booked. Go away.’”

Used to getting his way, Finley was not so easily brushed off. “His ego was huge,” says Gunderson, “and he had the money to spend. So he went to Brian again when The Beatles were in Los Angeles to play the Hollywood Bowl and wrote out a check for $150,000. Reportedly, Brian took it to this private mansion in L.A. where The Beatles were staying and said ‘What do you want me to do with this?’ And they basically said ‘We’ll do anything you want.’ And so The Beatles were booked to play Kansas City on the 17th of September, at just under $5,000 a minute.”

Naturally, Finley wanted the band to play a few extra songs since he had paid them so much to perform. But the set list for that tour, as well as the ones that would follow, was almost sacred. At one point, John Lennon himself rebuffed Finley, saying, “Chuck, we only do 11. That’s it.”

The Beatles and their manager, Brian Epstein (at left, in sunglasses and white shirt), arrive in Vancouver, B.C., 1964. Photo: Deni Eagland/Vancouver Sun PNG Merlin Archive.

“You’ll notice in many photographs in the book that they have set lists taped to their guitars,” says Gunderson. “Ringo had one on top of his bass drum. The shows would run anywhere from 28 to 34 minutes. They didn’t need to re-tape a new list every night. That was the set list.” In the end, the band relented a bit, adding a Little Richard-inspired medley of “Kansas City/Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey!” as the opening number for their Kansas City show.

“My friend Billy had offered me a ticket to the show. It was a done deal.”

All three tours featured supporting acts, so for fans paying the average ticket price of $4.50 in 1964 (Finley’s Kansas City shows were the most expensive, with some seats selling for $8.50), they were getting a lot more than just a half hour of The Beatles. The first tour featured Jackie DeShannon (she had a minor hit at the time with “Needles and Pins”), Bill Black’s Combo (Black had been Elvis Presley’s bass player, but he was too sick to play the tour), the Exciters (“Tell Him”), and the Righteous Brothers, who were stars in their own right but were replaced by Clarence “Frogman” Henry (“Ain’t Got No Home”) early in the tour after the Forest Hills, New York, performances.

“The Beatles had to be transported by helicopter from Manhattan to the Forest Hills shows,” says Gunderson, “so as the helicopter would come in for a landing, the Righteous Brothers were just drowned out.” For the Righteous Brothers, the noise from the audience was just as deafening, and equally insulting. “The whole time they were onstage, fans would be yelling, ‘We want The Beatles! We want The Beatles!’ Finally, they went to Brian and said, ‘Look, we’re done. We’re sick of this. We get paid more on the West Coast where the people know our music.’ So, they were graciously let out of the contract by Brian.”

This 1966 contract for two performances in Memphis, Tennessee, guarantees The Beatles and its supporting acts $50,000.

The 1965 tour featured support from Motown singer Brenda Holloway, the King Curtis Band, Cannibal and the Headhunters, a Brian Epstein-managed group called Sounds Incorporated, and the Discotheque Dancers. In 1966, Beatles fans were treated to performances by a Boston band called The Remains fronted by Barry Tashian, a short-lived group called The Cyrkle (their single was “Red Rubber Ball”), Bobby Hebb, and the Ronettes, who sang “Be My Baby” and their other hits without lead singer Ronnie Bennett, who was forbidden by her jealous future husband, producer Phil Spector, from going on the tour with The Beatles.

If the 1965 tour is remembered for being even more profitable than the first (it was completed in half the time, with many dates featuring two shows in the same venue), the 1966 tour was overshadowed by controversy over comments John Lennon had made many months earlier, in which he was quoted as saying that The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” While the context of the remark had been about the perception others had about The Beatles, a teen magazine called Datebook turned it into a boastful brag on the part of Lennon, provoking the burning of Beatles albums and protests at concerts by the Ku Klux Klan.

“The 1966 tour started off like the others,” says Gunderson. “People were like, ‘Hey, they’re coming back. This is great!’ Initially, ticket sales were brisk, and then Datebook came out with Lennon’s remark about Christianity, and that almost entirely derailed the tour.”

A promotion for the band’s 1965 show in Toronto.

Caught in this maelstrom was the venue for what would be their final show in San Francisco. “They were originally going to play the Cow Palace again,” says Gunderson of the site of their 1964 and 1965 concerts. But the Cow Palace only held 16,000 or so people, whereas nearby Candlestick Park could handle more than 40,000. “There’s an image in the book of a telegram to Brian suggesting that they use Candlestick for one show instead of the Cow Palace for two, as they had done in 1965.”

That suggestion was followed, but then the local promoters had to scramble to fill the large ballpark after Lennon’s allegedly controversial comment depressed ticket sales. Which led to a rarity in the history of Beatles tours in North American, a show poster.

“In three years of touring,” says Gunderson, “there were less than six posters. They didn’t need to do much advertising; they’d just put a few ads in the paper and go to local AM station. But there was a little bit more advertising during the ’66 tour,” including that handful of posters, although, says Gunderson, the one designed by Wes Wilson for Candlestick Park is hardly the rarest. “It’s a great poster,” he says, “but the rarest Beatles poster out there is probably for the show in Toronto in ’66. There are only a couple that I know of in existence.”

In 1966, local promoters hired psychedelic rock artist Wes Wilson to design a poster for what would be the last performance by The Beatles.

After the final chords of “Long Tall Sally” had faded away into the cool Candlestick night, The Beatles as a live, touring band were no more. Already burned out and dissatisfied by the fish-bowl existence that came with being on the road, they turned inward, focusing their considerable creative energies on studio albums.

In retrospect, it’s difficult to argue that giving up touring was the wrong decision, since it led directly to classics like “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” in 1967, “The White Album” in 1968, and “Abbey Road” in 1969. Those recordings, along with “Revolver” in 1966, are routinely ranked among the greatest albums of all time, whose audio quality stands in stark contrast to the dissonant cacophony that awaited North American fans in 1964, ’65, and ’66, when the best one could hope for was a fleeting glimpse of John, Paul, George, and Ringo straining to be heard in an echoing basketball arena or acoustically challenged baseball park.

“There were no monitors back then,” says Gunderson. “Ringo would often say, ‘I used to watch them wiggle their butts on stage, and that’s how I knew where I was in a song.’ Everything was just run through the amplification system of the venue. The sound was horrible.”

Even so, I wish I’d been there.

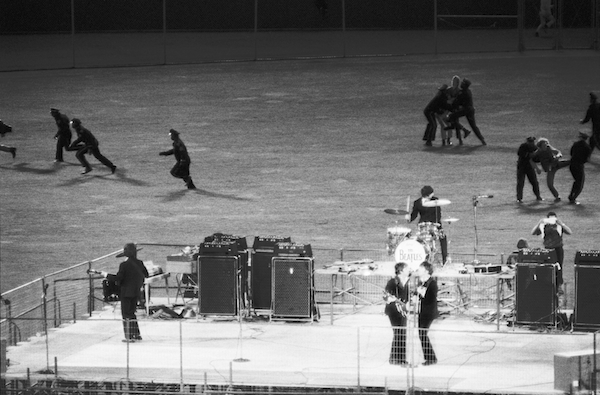

Police clear the field of fans as The Beatles perform in Candlestick Park, San Francisco, California, August 29, 1966. Photo: Bettmann/CORBIS.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Stephen M. H. Braitman on the British Invasion, from the Beatles to the Sex Pistols

Stephen M. H. Braitman on the British Invasion, from the Beatles to the Sex Pistols

Beatles 45s To Make You Twist and Shout

Beatles 45s To Make You Twist and Shout Stephen M. H. Braitman on the British Invasion, from the Beatles to the Sex Pistols

Stephen M. H. Braitman on the British Invasion, from the Beatles to the Sex Pistols A Mad Day Out with the Beatles, 1968

A Mad Day Out with the Beatles, 1968 BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of …

BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of … MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving…

MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Informative article, Ben. I too loved the Stones – but as a wise person once told me, “If I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard someone say “No thanks” to a Beatle concert, I’d have a nickel …” :)

Salt on the wound, Rob… ;-)

Nice article. I however feel it a shame that the Beatles never toured post ’66, as: a) they never went live with their best material; and b) they missed the technology upgrades which significantly enhanced the live show experience. It sends chills down my spine to think of a live set at the Garden featuring Come Together, Revolution, Hey Jude, Let it Be, Happiness is a Warm Gun, I Am the Walrus, so many other…

Of course I would’ve been too young to go or appreciate…

Bob Eubanks (Newlywed Game host) was the promoter who first arranged the Beatles tours in the US. Buy his book too. A very good read.

I turned down free tickets to a Stones concert because I was into the Beatles. Not quite as bad as Ben’s mistake, but still . . .

You want details on the US 64-66 tours? This is the end-all and be-all book and for those of you who look for Spizer-level research, this two volume set is exactly what you are looking for. Gorgeous photos, mind-blowing details and a heavy stock paper make this the best Beatles book published in 2014 and one of the best ever period. Without question.

Attended Sir Paul’s “Out There” concert here in Minneapolis last night (02 August). Incredible show because the songs were recreated and not reinvented for a younger audience. He played just shy of 3 hours; a true musician. Beatles music is timeless.