Looking at the bold, abstract forms on anti-syphilis posters from the late 1930s, confusion is to be expected: What exactly is this disease? And how do I catch it? Heading into World War II, America’s young military recruits weren’t very clear on the details either. In order to prevent a repeat of the venereal disease (VD) epidemic of World War I, the U.S. government teamed up with artists, designers, and ad-men to set the story straight, plastering public-health warnings on walls at bases and training facilities just as military ranks were growing exponentially.

“Fool the Axis—use Prophylaxis!”

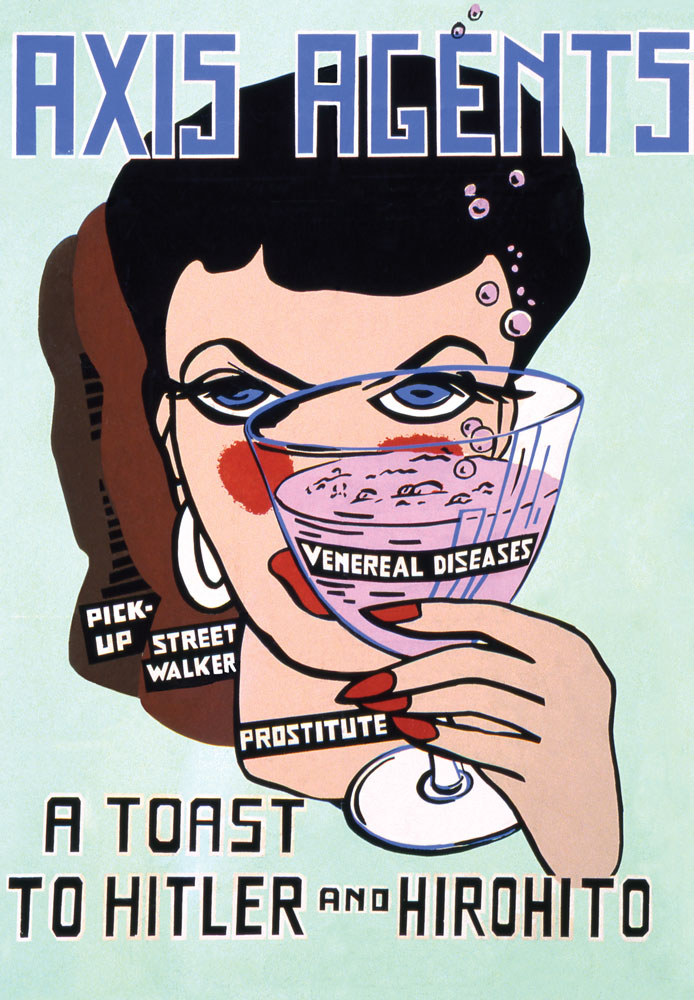

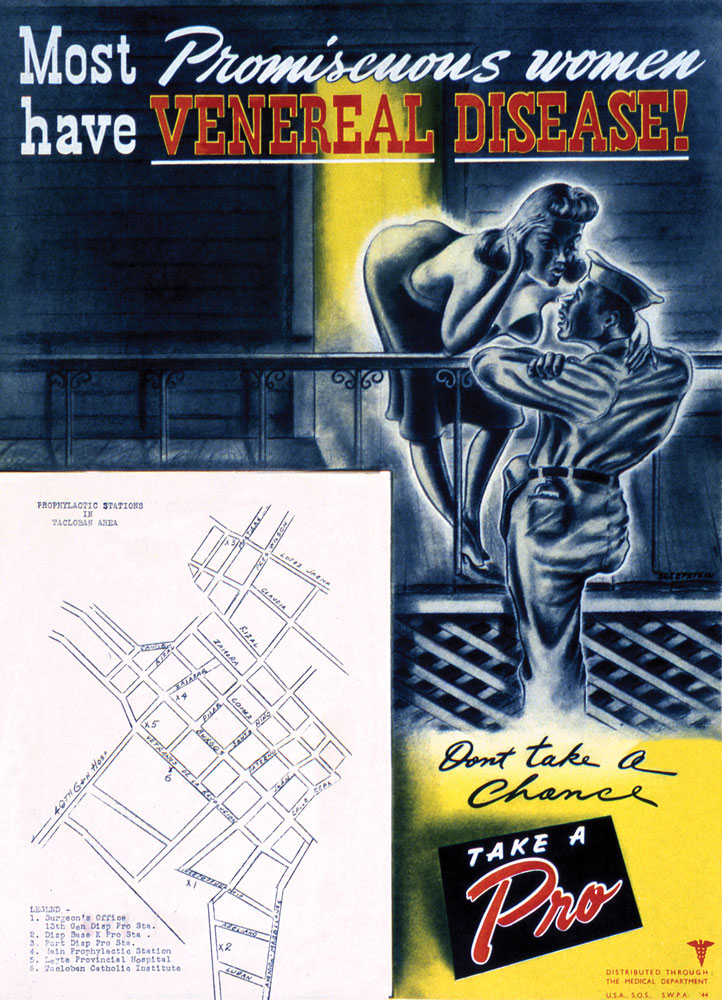

In many ways, such a coordinated public effort to alter sexual behavior was unprecedented. At a time when discussion of sexual activity was anything but frank, the VD posters of World War II addressed the topic directly using clinical language, ominous symbolic imagery, and jingoistic slogans to help enlisted men steer clear of sexually transmitted infections. While American sex-ed programs have taken many forms over the last hundred years, the military’s VD campaign left a unique trail of ephemera in its wake, featuring imagery that’s both gorgeous and deeply unsettling.

Last year, Ryan Mungia published a collection of VD posters entitled Protect Yourself, featuring exquisite images found at places like the National Archives and the National Library of Medicine. Mungia’s interest was first piqued while researching an upcoming book focusing on wartime Honolulu at the National Archives in D.C.

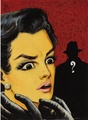

“My objective was to find photographs,” Mungia says, “but I came across this file folder peeking out of an open cabinet that said ‘VD Posters’ on it. Inside, I found a stash of 35mm slides of these posters, most of which ended up in the book. I guess you could say the subject chose me, since I didn’t set out to make a book on venereal disease, but became interested in the topic because of the graphic nature of the posters. The designs were really reminiscent of film noir or B-movie posters from the ’40s, those pulpy-style poster designs, and they also reminded me of the Works Progress Administration artwork, which I love.”

“My objective was to find photographs,” Mungia says, “but I came across this file folder peeking out of an open cabinet that said ‘VD Posters’ on it. Inside, I found a stash of 35mm slides of these posters, most of which ended up in the book. I guess you could say the subject chose me, since I didn’t set out to make a book on venereal disease, but became interested in the topic because of the graphic nature of the posters. The designs were really reminiscent of film noir or B-movie posters from the ’40s, those pulpy-style poster designs, and they also reminded me of the Works Progress Administration artwork, which I love.”

After he discovered the images at the National Archives, Mungia began researching in earnest, and realized that many of the VD posters were already on the Internet in various places. “But nobody had ever done a survey of them,” he says, “and I knew they deserved to be seen by a wider audience. I also realized that looking at a poster or a vintage photograph is so much better in print than on a computer screen.”

The federal government began its VD campaign in the 1930s aiming to reduce infections that might affect our ability to win the war. “On any given day during World War I, there were approximately 18,000 men who were taken ill with VD,” Mungia explains. “So when we started gearing up for the next major war, the U.S. military launched a pretty aggressive propaganda campaign including posters, pamphlets, and films to try to curb those numbers and keep soldiers healthy and able to fight.” At the time, most recruits were poorly informed about sexual health, and since strong antibiotics like penicillin weren’t widely available until the ’40s, the most common sexually transmitted infections—syphilis and gonorrhea—posed a much more serious threat than they do today.

Although the campaign initially drew inspiration from advertisements created by the Works Progress Administration (Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal jobs program), the military tried several approaches to reach young men, ranging from comic-book style pamphlets to realistic public-service announcements. “In the beginning, around 1941 or ’42, they hired a lot of artists through the WPA who had produced public-health posters a decade earlier,” says Mungia. “But there were several studies done to determine what kind of poster would be the most effective in delivering this message, and they concluded that people really responded to those which were more realistic and struck an emotional chord.”

“The WPA created beautiful posters that used a lot of bold shapes and colors,” continues Mungia, “but they relied on symbolism. These studies showed that some guys were actually confused by the WPA-style posters. The military’s solution was to go to Madison Avenue and consult some successful ad men, and they had those guys produce VD posters. The style of the posters changed over the course of the war from bold and symbolic to more realistic, almost magazine-style advertisements.”

Most of the VD-poster artists were anonymous, which Mungia believes was due to the nature of government-sponsored work. However, a few signed their names, such as Arthur Szyk, whose designs stand out because of his recognizable caricature style. VD posters were mostly obsolete by the end of 1945, due to a sharp drop in new infections, as well as medical advances like penicillin, which made treatment more effective.

Typical VD posters equated promiscuity with disease and moral weakness. “Fool the Axis—use Prophylaxis!” shouts the text of one poster from the 1940s. “VD can be cured, but there’s no medicine for regret,” reads another. As Jim Heimann writes in Protect Yourself, “The message was simple: Abstain from illicit sexual contact because it is unpatriotic, lethal, or detrimental to one’s health, and shameful to one’s spouse, girlfriend, or family back home. Sexual education, embedded in many of the posters, was secondary.”

“Once I was looking at them as a whole, I started to see certain themes arise,” Mungia says. “Women are often portrayed in a negative light, and it surprised me how they used Nazi imagery or depictions of Hitler and Mussolini to drive their message home. There’s somewhat of a disparity in them because the posters are very attractive, but their messages are very dark. There’s one in particular of a woman who looks like a skeleton and is walking arm in arm with two Axis leaders, Hitler and Hirohito. I think it’s so interesting that they suggest that the Axis powers were behind venereal disease.”

(All images courtesy Ryan Mungia from Protect Yourself: Venereal Disease Posters of World War II)

Getting It On: The Covert History of the American Condom

Getting It On: The Covert History of the American Condom

Slut-Shaming, Eugenics, and Donald Duck: The Scandalous History of Sex-Ed Movies

Slut-Shaming, Eugenics, and Donald Duck: The Scandalous History of Sex-Ed Movies Getting It On: The Covert History of the American Condom

Getting It On: The Covert History of the American Condom Cheap Thrills: The Freakish Fantasy Art of Mexican Pulp Paperbacks

Cheap Thrills: The Freakish Fantasy Art of Mexican Pulp Paperbacks Military Posters and PropagandaWWI Propaganda Posters

During World War I, the U.S. government, contractor…

Military Posters and PropagandaWWI Propaganda Posters

During World War I, the U.S. government, contractor… Military and WartimeMilitary and wartime antiques and memorabilia include an enormously wide va…

Military and WartimeMilitary and wartime antiques and memorabilia include an enormously wide va… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Imagine running these campaigns today. Oh boy the media firestorm! Congressional hearings!

This is fascinating. Thanks for sharing.

Then, the classic: “A Night with Venus, a Lifetime with Mercury.” Before antibiotics, the treatment used heavy metal compounds such as mercury and arsenic (Salvarsan 606), invented in 1907.

This is great. I would love to own some of the posters. They would go over big in the nursing home !!!

Nothing like government sponsored art to push s political agenda. Grateful that the same government allows public dissection of a fascinating folly decades later. And–grateful that you have the talent and insight to do it so well. Another fine article, Hunter.

In the first edition of Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (1941), three chapters were dedicated to the treatment of syphilis. Treatment consisted of sixty weeks of treatment with heavy metals, bismuth or mercury and arsenic. The authors also opined that mercury treatment never cured a single case of syphilis.

I can understand why some of WWII’s young soldiers were confused by the initial posters. The one with the dinosaurs implies that one gets VD from the brontosaurus!

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that ‘loose women’ are represented as both the source and vector of contagion, and of course married people never have sex with others. The blood test for syphilis prerequisite for a marriage certificate always boggled my mind.

I have a WWI pamphlet given to doe-boys going to WWI. One side has a message about staying true to your sweetheart and untrue scare tactics. The other has a hand written note from T Roosevelt saying to do the right thing and stay true to you gal back home.

Do you know where I can find more info on VD and WWI

Thanks

Mike