At one point, Anita Pointer—lead vocalist and writer for the Pointer Sisters’ Top 10 hit “I’m So Excited”—was one of the most famous women in the world. During the early ’80s, she and her sisters June and Ruth tore up the pop music charts with singles like “Jump (For My Love),” “Neutron Dance,” “Automatic,” “He’s So Shy,” and “Slow Hand.” If you search for the girl group on YouTube and watch videos from the height of their popularity, you’ll be whisked back on a buoyant romp of sequins, neon, shoulder pads, sky-high pink and blue hair, and relentlessly optimistic synthesizer beats. “In the ’80s, we were hot, boy, I’ll tell you,” Anita remembers. “Before Destiny’s Child came along, it was the Pointer Sisters.”

“We were out there marching in the ’60s, and racists are still killing black people today.”

But the Pointer Sisters’ story goes much deeper than the glittery MTV-era glee. The six Pointer children—two boys, Aaron and Fritz, and four girls, Ruth, Anita, Bonnie, and June—grew up poor preacher’s kids in 1950s Oakland, California, a predominantly black city across the bay from San Francisco. Anita Pointer also spent part of her childhood in the small town of Prescott, Arkansas, with her grandparents, facing Jim Crow segregation. As a young woman in 1960s Oakland, she protested racism and police violence.

Anita joined with her younger sisters Bonnie and June to form the Pointer Sisters in 1969, and the group sang backup for some of the bright lights of San Francisco’s ’60s music scene, including Elvin Bishop, Grace Slick, Taj Mahal, and Traffic co-founder Dave Mason. The sisters developed a unique look by digging up high-quality clothes and accessories from the 1940s and wearing head-to-toe vintage onstage. Their eldest sister, Ruth, joined the group in 1972, forming a quartet, and in 1973, the Blue Thumb jazz label released their self-titled album that defied the “black music” R&B standards of the decade. It included country, be-bop, boogie-woogie, and funk sounds, and by the following year, it had sold enough to receive gold certification from the record industry.

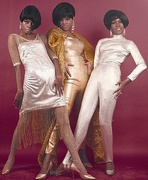

Top: Anita Pointer poses with her black memorabilia display in her Beverly Hills home. (Photo by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger) Above: The Pointer Sisters—from left, June, Anita, and Ruth—topped the charts in the ’80s. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

After that, the Pointer Sisters became the first contemporary-music act to sing at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee, thanks to the Anita and Bonnie-penned country tune “Fairytale.” They wrote songs with R&B legend Stevie Wonder, starred and sang in the classic film “Car Wash,” and made endless television appearances on programs such as “Sesame Street,” “The Carol Burnett Show,” and “The Midnight Special.” Bonnie left the group in 1976 to pursue her own music career, just a few years before the trio became ubiquitous. While the Pointer Sisters’ popularity peaked 30 years ago, the trio never stopped performing. In 1995 and 1996, the sisters toured with the Fats Waller-inspired musical “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” These days, Ruth’s daughter Issa and granddaughter Sadako now alternately sing for June Pointer, who died of cancer in 2006.

“The only other black people at the party were the cook and the servers. So the Pointer Sisters showed up, and the door people assumed we were servers, too, and sent us to the back door.”

What most people don’t know about Anita Pointer is that she’s also a serious collector of black memorabilia. This collecting category encompasses exoticized images of Africans made by Europeans, artifacts of African American slavery, mementos of Jim Crow-era segregation, objects associated with black celebrities, and memorabilia from the Civil Rights Movement. The most controversial type of black memorabilia are antiques designed with racist caricatures, based on stereotypes that often originated in minstrel-show blackface performances. Such imagery proliferated after the Civil War to promote the belief that white people were superior to newly freed black people. Typically, the caricatures—which could be attached to anything from toys to cookie jars to advertising tins—depict black people as happy-go-lucky buffoons and servile simpletons, such as Mammy and Uncle Tom, with oversize eyes and lips.

Today, Pointer has so much black memorabilia from all over the world, she’s estimated it would “probably take up a basketball court.” Her collection includes a tin of Nigger Hair Tobacco, children’s books like Ten Little Niggers and Little Black Sambo, an Aunt Jemima cast-iron bank, water glasses and a dinner plate from a restaurant chain called Coon Chicken Inn, “Mammy and Chef” wall plaques, Staffordshire figurines depicting Uncle Tom and Eve, Golliwogs from England, blackamoor ashtrays, and even a set of slave shackles. Earlier this year, she told “AARP Magazine” that a Sotheby’s appraiser was wowed by her collection because he’d never seen half the stuff she’d collected. Pointer buys these objects to serve as a stark reminder of the racism she’s fought against her whole life. We spoke with Pointer on the phone from her home in Beverly Hills about her collection and how it ties to her personal history.

Collectors Weekly: How did you get into collecting black memorabilia?

Anita Pointer found her first piece of black memorabilia, Dancing Sam, at an Arkansas antiques shop. (Photo by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

Pointer: I’ve always loved antiques, even as a little girl. My grandmother and my great-grandmother kept these trunks full of old clothes in the garage. Me and my sister Ruth used to play in those old clothes, putting them on and walking around the neighborhood. People would laugh at us, but we didn’t care. We’d be clonking down the street in old high-heeled shoes. It was so funny. I just love the memories of old things, so I guess it was a natural evolution for me to get into collecting. But as a child, I never saw any of the black memorabilia that I’m collecting now. Those racist caricatures weren’t in our home. I suppose white people made these caricatures for themselves—to laugh at them, I guess.

I first discovered black memorabilia in 1980. We were headed to Prescott, Arkansas, where my momma’s from, and we saw an antiques store. I’ve always loved looking around antiques stores, so we stopped. That’s when I saw Dancing Sam, the first piece of black memorabilia that I bought. He was a painted black wooden doll, with a wire holder on his back and little hinges on his limbs. You hold him on top of a plywood platform, and you tap the plywood so he jumps and dances around. The packaging says, “Hours and hours of fun for your children.” [Laughs.] I was like, “Whoa, you mean kids would sit there and play with this for hours?” Dancing Sam was black with white lips, like blackface makeup, so he intrigued me. It all started there. I began going to antiques stores and picking up black memorabilia wherever I could.

Years later, in 1998, I was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame, in Little Rock, Arkansas. They gave me an award for my contribution to music and had a big to-do for it, where I met Governor Mike Huckabee.

Collectors Weekly: What was your childhood like?

The Pointers’ father, Elton, was the pastor at the West Oakland Church of God, pictured in the 1950s. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

Pointer: Our dad was the pastor of the West Oakland Church of God, and our mom was the assistant pastor. So we couldn’t do anything. Growing up, it was all about the church. We couldn’t go to parties; we couldn’t go to movies. The first movie I saw was “The Ten Commandments,” and the whole family went because it was about God. Now I understand the control they had over us. There are so many horrible things in this world that you need to protect your kids from, especially when you’ve got six kids that are rambunctious, funny, crazy, and smart. When Mom and Dad were gone, we would just take over the house and have our times. We’d have talent shows in the living rooms. Me and Ruthie would stand on the piano stool and tuck our dresses into our panties to make them look like little ballerina tutus, and we’d sing.

I went to Oakland Technical High School and graduated in 1965. We had the best drama teacher, Tom Whayne, and the best drama class. Ted Lange, who’s Isaac on “The Love Boat,” went to my school, and we were in all these plays together, like “Macbeth” and “The Skin of Our Teeth.” I loved going to school at Tech. I was on every committee. I was the chairman of the senior ball committee. I was on the student senate. I was a Delphian, which is an academic honor society, and a thespian in drama. I was really into school, but I wasn’t that popular. I couldn’t even get a date after being the chairman of the senior ball committee.

Collectors Weekly: When did you start singing?

From left, Ruth, June, and Anita attend a church service in 1956. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

Pointer: Just like so many other black artists, we got our musical training from church because we couldn’t afford singing lessons. My siblings and I sang in the church choir as little kids; we were the little soldiers when we were 6 and 7 and 8. Then, we gradually moved up to the senior choir, and that’s where we got our training on the different parts—soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. It helped us because we were truly into harmonizing, and as a Pointer Sister, you have to have your own note, or you’re in trouble.

School also gave me some good training. I was in the choir at Westlake Junior High School in Oakland, where I had the best teacher, Miss Gillette. She gave her students breathing techniques and taught us how to use our diaphragms and enunciate lyrics. Miss Gillette came to a Pointer Sisters show in Europe while we were on the road back in the ’80s. It was so exciting to see her again.

Collectors Weekly: As a child, you also spent some time in Jim Crow-era Arkansas?

A matchbook from Anita Pointer’s collection warned that only white patrons were welcome at Club Plantation. (Photo by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

Pointer: Yeah, it was shocking. My parents would drive our family from Oakland across the country every year to visit my mother’s parents in Prescott, Arkansas. My dad would also speak at church conventions around the South. One year in the late ’50s, I said wanted to stay in Prescott, and Mom said that I could go back and go to school there for the fifth grade.

The people there were living so poorly; I couldn’t believe it. I thought we were poor in Oakland—my dad was a minister, and we barely made it. Our church would have a pastor’s aid day, where the church members would bring food for us. My grandparents in Prescott were also not well off, but they were not the poorest people there. They were the ones who had a TV and a car. The other kids would come to our house to watch television.

The poorest people in Prescott still had outdoor toilets. They had no running water in the house. I was just amazed. The kids only got shoes in the winter. They would run—I mean run—on gravel roads barefoot. I saw these kids running on the gravel, and I said, “I’m going to try that.” Oh, my God, I thought my feet were going to be cut to shreds. I couldn’t do it, but their feet were so conditioned to walk on the gravel roads barefoot. I used to help them do their laundry. They made their own soap—these big, ol’ chunks of lye soap—and they’d have a scrub board and a big, ol’ round tub out in the backyard. You’d think it was the turn of the century, but this was the ’50s.

Pointer owns this “Dinah” cast-iron mechanical bank from early 20th century England. To operate it, you put a coin in Dinah’s hand, press a lever on her shoulder, and watch her deposit the coin into her mouth. (Photo by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

One day, my grandmother let me go pick cotton. That was fun. [Laughs.] I couldn’t believe how much you had to pick to get a dollar. The bag would be 25 feet long, and you had to fill it up. Then you’d get maybe 50 cents. It was a learning experience for me, but I saw people out there with their families trying to make money for their livelihoods. It was unreal.

“Maybe that’s why I collect these racist things: I want to get them off the market. But at the same time, they remind me of who I am, as compared with what the world thinks of me.”

The schools were segregated, and the black school had leaky ceilings. When it would rain, the kids would have to run around and put buckets all over the place. And we had to wash the windows in the school. They also didn’t have a science lab at the black school; they had none of the stuff that the white school had. In downtown Prescott, there were the signs on the water faucets, “colored” on one side and “white” on the other side. Me and my friends would go downtown and drink on the white side and then run away to make the townspeople mad. At the movie theaters, we couldn’t go in the front door. We had to go to the back and up these stairs to the balcony. It was the same thing in restaurants; you couldn’t go to the front door. You had to go pick up your food on the side. I couldn’t believe it.

Oh my goodness, it was such a different place than Oakland, California. I went back to Prescott for the seventh grade and the 10th grade, so I experienced elementary, junior high, and high school there. I love it there. I love the people. I love the smell of the place and the whole country vibe. I have to get back there soon.

Collectors Weekly: In the ’50s, Oakland had less obvious segregation?

Pointer: Yes, it was less obvious. We went to Cole Elementary School in Oakland, which was basically all black. But Patsy Reposa, my neighbor who was my best friend in school, was white and Italian. There were a few white kids in our school, but not many. The white kids went to school in different areas of town.

Collectors Weekly: Were you involved in the Civil Rights Movement as a teenager in the ’60s?

Named after a racial slur in 1925, the Coon Chicken Inn restaurant chain thrived for decades in non-Southern locales: Salt Lake City, Seattle, and Portland. Pointer owns several items from the chain, including this menu. (Pictured front and back; photos by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

Pointer: Just after high school, I remember carrying my baby daughter, Jada, around and catching buses to rallies in San Francisco. We traveled to the first Black Power and Arts Conference in L.A. and did an African fashion show, modeling African dresses, hats, and head ties. This was 1967, and people in Oakland were trying to get to Lowndes County, Alabama, to support the black people there who were trying to exercise their right to vote.

“We’re beautiful, and we’re not going around getting kicked in the head by mules like the cast-iron banks depict.”

My brother Fritz Pointer had gone away to college and majored in African studies, sociology, and theology. He came back to Oakland with all this information about politics, race, and religion, so he started a free student study group. If you wanted to come and didn’t have a way, he’d pick you up. In these free classes, he taught me more about black history than I ever learned in the school, hoo! Going to school in Oakland, the only things we ever heard were that black people picked cotton and that one guy, George Washington Carver, invented peanut butter. That was it! I was like, “Come on, this is cold-blooded. You won’t even give us our history!” [Laughs.]

We would also go to civil-rights meetings, which is where I met Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Muhammad Ali even came and spoke to our group. Those were some courageous times for us because we were young and invincible. Both black and white kids were a part of the movement. We were all good friends with Black Panther Party leaders Eldridge Cleaver, Kathleen Cleaver, Bobby Seale, and Huey P. Newton. We were with Huey the night he got shot by the cops; he was leaving the student study group we were having at our cultural center. We all rushed to the hospital. The police had shot him and put him under arrest in his hospital bed. And, Lord have mercy, we got out there trying to protest, shouting, “Free Huey!” The cops came out with shotguns and dogs and told us, “Everybody, disperse!” We started running because those Oakland police will shoot you. They don’t care. If you don’t move, you’re dead. So we got out of there.

A slave shackle from Pointer’s collection. (Photo by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

It was tough. It’s still tough. I can’t believe the things that the American system puts people through just because of race. It’s unbelievable. The so-called justice system is just so horribly corrupt, to this day. We’re repeating history. We were out there marching in the ’60s, and racists are still killing black people today. Young people are marching for freedom now and trying to get the government to take down that stupid Confederate flag. I swear, come on! White people have got to understand that black people built this country, too. We were here doing all that labor for 400 years with no pay. Why don’t we get a tax break? Why do the corporations get a tax break?

I’m so disgusted with the American system. Maybe that’s why I collect these racist things, because I want to get them off the market. But at the same time, they remind me of who I am, as compared with what the world thinks of me, and that I have to prove them wrong. We’re not buffoons, we’re not stupid, and we’re not just dancing and singing all the time—even though that’s what I do. [Laughs.] But everybody is not like me, okay? My older brother Aaron, he played pro baseball, and then he was an NFL referee for many years. He was also president of his high-school class, and he got a scholarship to college. My brother Fritz he was drafted by many basketball teams, including the Harlem Globetrotters. But Fritz didn’t want to go, because he felt that all American society would allow black men to do at the time is become an athlete. So he chose to be a teacher. And he became a great professor.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me how the Pointer Sisters formed?

A souvenir program honors Elton Pointer’s 22nd year as pastor of the West Oakland Church of God. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

Pointer: We started as itty-bitty girls, singing in church as the Little Pointer Sisters. Some of the members didn’t like our singing too much because we’d go get it, jazzing things up. When I was 20 in 1968, I saw Bonnie and June singing with the Northern California State Youth Choir, which was touring with a hit song, “Oh Happy Day” featuring Dorothy Combs Morrison. I went to see them at Fillmore West in San Francisco one night, and I just lost it. I sat in that audience, and I cried, and I sang along. The next day, I quit my job. I said, “I’ve got to sing! I’ve got to do it. Oh my God! I want this so bad!”

I had been working at a law office in Berkeley for maybe a year and a half, and it was good job. But when it hit me at that show how good it felt to sing, I said, “I’ve got to try!” After I joined the choir, it split in two. Edwin Hawkins led one choir, and Betty Watson the other. Since Betty was our friend, we went with her. We rehearsed and rehearsed to go on the road. The day of the trip, the organizers came to my mom’s house and said the tour was canceled. It was a shame because Mom had already gone out and gotten a $300 loan to help pay for the trip. When you have to get a $300 loan, that’s really poor. Mom did what she could for us.

I had this guy friend who thought he knew everything, and he said wanted to introduce me and my younger sisters to some people, producer friends in his hometown of Houston, Texas. He was a car dealer, so he always had fancy cars, and he wanted to drive the three of us to Texas. He said he knew all these music-industry people in Texas who could get us a record deal. But he didn’t have anything together—he was just a big puff of smoke. In Texas, everybody he talked to told us to come back the next day, and when we’d go back, the doors would be locked. It was disgusting. We went to a couple of little nightclubs that let us sing, that’s about it.

The Pointer Sisters—Bonnie, Ruth, Anita, and June—play around in vintage clothes in the 1970s. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

This guy got mad at me because we wouldn’t obey him. I said, “I think you’ve got the wrong three girls. Me and my sisters are not your women. We are singers, and we are on our own. We are not what you think we are.” Oh my God, he got mad and put us out, and we didn’t know anybody in Houston. A girl we met in the club the night before, we begged her to let us sleep on her couch. She did, but her house was full of roaches, so we had a horrible time.

Bonnie happened to have a card in her purse from David Rubinson, who ran the Fillmore and Winterland music venues with Bill Graham in San Francisco. I called and told him, “We’ll sing for you forever if you get us home,” and he sent us airplane tickets. As soon as we got back to Oakland, he called us to San Francisco to record backup vocals with a group called Sunbear. Then we recorded with Elvin Bishop and Grace Slick, and we started going on the road with Elvin as his backup singers. We became the go-to backup singers for the San Francisco Bay Area. It was great training because when you’re a backup singer, you get a chance to see what all the people in the background go through. You learn how to treat your people because you’ve been there.

Collectors Weekly: The early ’70s were a great time to be a backup singer in San Francisco, music-wise.

The Pointer Sisters performed with Flip Wilson on television in the early 1970s. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

Pointer: Oh, yeah, it was such a great time. We went to London on tour with Dave Mason in the 1970s. We had our little sexy clothes on, and we’d be dancing, just flying across those big, old stages. His managers would tell us, “You guys calm down a little bit. You’re upstaging the star.” We sang a song we wrote about my daughter, “Jada,” for Dave Mason. He said, “You’ve got to sing this to David Rubinson!” So we sang it to him, too, and he said, “Oh, my God, I love that song.”

We ended up getting a deal with Atlantic Records. We were doing backup singing with Elvin Bishop at the Whisky A Go Go in L.A., and Jerry Wexler, who was Aretha Franklin’s producer, came to our show. He called David and said, “I love these girls. I want to sign them. I want to send them out to record right away.” So like that, we were gone to New Orleans to meet with Wardell Quezergue, who was the producer for Jean Knight, who sang “Mr. Big Stuff.”

“Some of the old clothes would just tear up onstage, especially velvet. I’d look back, and there was half of the dress on the floor, because it had disintegrated under the lights.”

We got there and started singing for them. We were singing songs we were into, rock ’n’ roll, folky stuff, and country stuff—songs we later recorded. But they just started laughing. We said, “What are you laughing at?” And they said, “Black girls can’t sing no songs like that!” They rearranged our music, turning our country songs into R&B songs. We got back to San Francisco, and David Rubinson had a fit. He took that record and threw it across his office. I swear, he scared me. He was so mad. He said, “I didn’t want them to try to put you in a mold!” At the time, The Jackson 5 were hot, and so were The Honey Cone, which was the female equivalent of The Jackson 5. They were telling us in New Orleans that we’ve got to sound like The Honey Cone. We said, “We don’t want to sound like an imitation of another group! That’s the whole idea, to do something different!” But they didn’t get it. We didn’t like that material, but we sang it anyway, and it didn’t go anywhere but to our house and up against David’s wall.

We got out of that contract, and David shopped for a new record deal. He later admitted it took a long time. He went to every major record label, and they turned us down. I didn’t realize he had to get that deep into it. But he got us a deal with Blue Thumb, which was a jazz label. We had some jazz, some country, and some R&B on the first album, and the label loved it. Our first album went gold, and in those days, that was a big deal.

Collectors Weekly: So you guys had an old-fashioned vibe going on?

The Pointer Sisters accept their first Grammy for best country vocal performance by a duo or group for the year 1974. (Via ThePointerSisters.com)

Pointer: Yeah, we didn’t want to be pigeonholed into one kind of music. We tried doing a little bit of everything, and we were pretty successful. Our first Grammy Award was for a country song that we wrote. “Fairytale” won best country vocal performance by a duo or group for the year 1974, and Elvis Presley recorded a cover of it in 1975. We were the first black female group to ever play at the Grand Ole Opry. I don’t know if any other black female groups have performed there since. We didn’t realize how much some people didn’t want us there!

“We had our little sexy clothes on, and we’d be dancing, just flying across those big, old stages. They would tell us, ‘You’re upstaging the star.’”

We were first invited to perform at the Opry in 1974, but they didn’t know we were black for some reason—I don’t understand it myself. We sound black to me on our record, but they said they didn’t know. We got up on the stage and started singing, and this guy stood up in the audience and said, “Hot damn, them gals is black!” The audience cracked up. He liked us, though, so it was good. We sang “Fairytale” twice that night. We went back and sang there again years later. In 1986, I went back with Earl Thomas Conley because we had a hit country duet together called “Too Many Times.” That year, he and I were presenters at the Country Music Awards, which was very scary, because I didn’t even have my sisters there. I think Charley Pride was there that night, and he was the only other black performer. Everybody else was looking at us like, what are you doing here?

There have been so many crazy incidences like that. Industry people had a big party for us at a huge country mansion. The only other black people at the party were the cook and the servers. So the Pointer Sisters showed up, and the door people assumed we were servers, too, and sent us to the back door. Our manager had a fit about that. I guess with any job or any career, a black person could be confronted with racism and prejudice. It’s always shocking and disturbing. But what can we do? I don’t know if America will ever get it right before I’m gone. Maybe in another lifetime, people will understand that we’re all people and we should love everybody.

Collectors Weekly: When the Pointer Sisters first started, you all were into wearing vintage clothes?

This shot of the Pointer Sisters in their own vintage clothes (Anita is on the far right) was inverted and used as the cover of their first album, “The Pointer Sisters,” in 1973.

Pointer: Mmm-hmm. Oh, I loved it. I thought that was so cool. We had the idea to buy used clothes originally from expensive department stores like I. Magnin and Saks Fifth Avenue—you know, clothes that we couldn’t afford new. We would go to antiques places and find these vintage clothes, which would be our party outfits. All those clothes on our first album cover came from our closets. We didn’t have a stylist. We had makeup people there, but we brought our own clothes. David had said, “You guys dress so cool. Bring that stuff you guys wear.” Some of the old clothes would just tear up onstage, especially velvet. I’d look back, and there was half of the dress on the floor, because it had disintegrated under the lights. Those clothes were so fun.

Collectors Weekly: You also had an antiques-filled apartment?

Pointer: When we lived in San Francisco, me and Bonnie and June lived in a shaky flat that we wrote a song about, “Shaky Flat Blues.” We used to go to this place called Busvan that had all these great antiques—I mean, anything you’d want from furniture to clothes, purses, and hats. We would go there and get used furniture and novelty items to sit on the fireplace. It just made sense to buy secondhand instead of going to new furniture stores and paying all that money. When I moved to L.A., I did the same thing. I went down to Melrose and got a whole bunch of secondhand furniture for my apartment. People give such great stuff away. I’m like, “I’ll take that!”

Collectors Weekly: I had no idea until recently that you all sang the “Pinball Number Count” song for “Sesame Street,” which debuted in 1977.

Pointer: I love that song, “One-two-three-four-five, six-seven-eight-nine-10, 11-12!” [Hums a few bars.] We had to learn it, like, in 10 minutes, and that’s a hard thing for four people singing in harmony. We were like, “Whoa, this is something.” It was a challenge for us, but we did it so good and fast. We brought our kids with us that day, but they didn’t sing with us. We were doing a lot of stuff for TV then. Previously, we performed on “Sesame Street” in 1975 as guests.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me about your music collection?

Pointer: I started accumulating vinyl albums when I bought my ex-assistant and friend Gina Glasscock’s vast record collection, which has everything from Jimi Hendrix to Madonna. And I have all the vinyl LPs and 45s for our Pointer Sisters albums. It’s a history lesson to listen to records by Fats Waller, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sarah Vaughan—all these old musicians that went before me and paved the way. I don’t take them lightly. They really made a difference in my life. That’s why I keep a lot of these old things. This stuff reminds me of how I started off learning about music.

I’ve also got the “We Are the World” music cassette and the sheet music, which I had autographed by everybody who was there that night. That was a hell of a night. Oh, my God, it was so wonderful and magical. We all got together, all the hot artists of 1985—Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Quincy Jones, Tina Turner, Bruce Springsteen, everybody—and went into the studio. When we came out of there, the sun was up. I couldn’t believe it. I spent the night with Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie, at the same time. That was incredible.

Collectors Weekly: What do you have in your black memorabilia collection?

Anita Pointer collected these Mammy and Chef salt-and-pepper shakers, which were originally New Orleans souvenirs. (Photo by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

Pointer: It encompasses all representations of black people, from negative to positive. I wish I had focused on one type of thing, but I just bought every piece of black memorabilia I found. There wasn’t a whole lot of it still out there when I started collecting. I don’t know who got it all—maybe Whoopi Goldberg? I’ve found paper stuff like postcards and advertisements. I have a list of slave auctions. I have ceramics and wooden objects. I have potholders, cookie jars, banks, toys, dolls, aprons, hair combs, and hair-grease tins. I have collected Michael Jackson memorabilia, Michael Jordan memorabilia, Muhammad Ali memorabilia, Louis Armstrong “Satchmo” memorabilia, and dolls of Flip Wilson. I just collected anything that I saw that was related to the black experience—and also some Native American objects like kachina dolls.

“I can’t believe the things that the American system puts people through just because of race, to this day. We’re repeating history.”

There are a lot of racist caricatures. I’ve donated an image from a Cream of Wheat advertising campaign to the Civil Rights Institute in Birmingham, Alabama. It shows a black man pulling a cart like a mule with a little white boy driving the cart with a whip. It’s just despicable. But this reminds me that everybody don’t love you and that you have to prove them wrong. You’re not a buffoon. The artists tried to depict black people in an insulting way, but I think big lips and big booties are beautiful. Some of the caricatures look beautiful to me, even if they were meant to be jokes. Now all the white starlets are trying to get that look, filling their lips with injections and getting fake booties. We’ve always had that!

These items serve as a history lesson. When the Civil War ended, white people did not want to praise black people. They wanted white people to continue to think that black people were stupid and couldn’t do anything but sing and dance, take care of their kids, and work for them for free. That’s the disgusting part. People today have to search their hearts to see if they have any evil feelings toward another race.

Collectors Weekly: Do you think it’s important for people to know this stuff exists?

To release the coin into this 1879 bank called Always Did Spise a Mule, you press a lever that prompts the mule to kick the black boy. From Anita Pointer’s collection. (Photos by Roxie Mckain and Jacinta Dellinger)

Pointer: Yes, I really do. My granddaughter, Roxie, never knew about any of this stuff. She was never confronted with a “whites on one side and coloreds on the other side” sign. It’s important to know your history; if you don’t, you’re doomed to repeat it. I don’t ever want people to think this way about my people ever again, because it’s not so. We’re beautiful, and we’re not going around getting kicked in the head by mules like the cast-iron banks depict. It may seem like it’s getting better, but when I saw the news about the mass murder at the church in Charleston, South Carolina—holy shit! How would you know that someone is going to be that evil still in this day? I just couldn’t believe that boy walked into that church and shot all those people. It hurt my heart to see that we’re still going through this shit, when we fought so hard in the ’60s to make people appreciate that we are human and we do matter. [Her voice cracks.] Our racist society can still destroy black people’s lives—with mass incarceration, bad bank loans, unemployment, so many things—and it makes me cry. It hurts me to see that there are so many evil people in this world still.

I am grateful for the #BlackLivesMatter campaign. For many hundreds of years, white supremacists would kill our people with no repercussions. It’s horrible the way people think that they are better than others. I just don’t get it. I wasn’t raised that way.

More Items From Anita Pointer’s Black Memorabilia Collection

(Find out about upcoming Pointer Sisters shows at their web site. Learn more about black memorabilia at the web site of Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Black Glamour Power: The Stars Who Blazed a Trail for Beyoncé and Lupita Nyong'o

Black Glamour Power: The Stars Who Blazed a Trail for Beyoncé and Lupita Nyong'o

How America Bought and Sold Racism, and Why It Still Matters

How America Bought and Sold Racism, and Why It Still Matters Black Glamour Power: The Stars Who Blazed a Trail for Beyoncé and Lupita Nyong'o

Black Glamour Power: The Stars Who Blazed a Trail for Beyoncé and Lupita Nyong'o The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and …

Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and … RecordsMore than a digitally perfect CD, and way more than a compressed audio file…

RecordsMore than a digitally perfect CD, and way more than a compressed audio file… Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in…

Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in… MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving…

MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I’m so greatful to God to have met you all 39 years ago at the Civic Auditorium here in San Francisco Thanks to Jada who stood by my side the day of the show. And asked me if i wanted to meed you all after the show. Of course i answered with a big YES. At that time i was your biggest fan, still is to this day and will always be. I still have my autographed photos of you all and the book. Mother Pointer, which we all called her when i was allowed to go up to the house in Novato to keep the house and make sure Jada, Malik and Faun get to school on time while Mother went with you all on ture. I so miss Grandma Roxie, Dad, Mother, Jada and June. I love you . If i could ever be any help to you. Don’t hesitate to ask me. God Bless you.

I am your fan Anita! Your music with your sisters made life in this world seem so wonderful as I grew up. How remarkable, coming across your site here! Your collection is so historically enlightening! You have always been and still remain an inspiration and a role model. Isn’t it incredible that after all these years, age has even enhanced your beauty!

Loved your music Ms. Pointer. One of my favorites was “Yes we can can”. Thank you for sharing your musical talents, your collection and the historical meaning it has to you.

Gosh, My older brother introduced me to your music. You ladies are an incredible musical blessing and and inspiration to me. I love all of your music – Happiness is my absolute favorite – Your music is so uplifting and full of joy.

LOVED your music!! Got me through tough times. Your collection is fabulous too! I would have loved to use this interview and photos of your collection when I was teaching. I’ll forward this site to my colleagues! Thank you!

This article was interesting and expanded information featured in AARP. I have an artifact I would like to donate to the Jim Crow Museum for preservation. It was in my grandparent’s household for many years. I offered it to a museum in Little Rock, but they declined it. Should I just contact them directly or can you suggest someone in particular to contact? Thank you for all your wonderful music!

Thank YOU, I have a lot of respect for you and your sisters for doing a wide variety of music and not pidgeonholed into a “type”.

I wish whoever interviewed you would’ve had a personality… the questions asked should have flowed more from observing your collection and your answers..they should’ve done their homework and known everything about you when they started the interview!

I liked what you said about taking these things off the market, and the constant reminder of who we REALLY are…not these characutures. I bought 3 signs off of Ebay from the jim crow south segregation. I didn’t want some racist to hang them in his man cave!

Personally I am done with trying to”prove” my worth to others. If they can’t see it I don’t need to be around them. The most important person to know my worth is me…its hard to hang onto at times, there is still a huge amt of negative portrayals of African Americans around, unfortunately.

Thank you again for sharing your thoughts and collection with us.

Wow, if it weren’t for the accompanying text, I wouldn’t have recognized one of the Pointer Sisters as she looked in 2015.

I think she should label her collection “Stereotypical Black Memorabilia”. Certainly blacks didn’t portray themselves that way.

Hard to believe she’s 67 in these pictures, she looks amazing