When a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck San Francisco on the morning of April 18, 1906, it triggered three days of fires, destroying almost 30,000 structures and leaving more than half the city’s residents homeless. Once the embers cooled, the quake spurred an equally thorough rebuilding effort, first for roofs over people’s heads, but then for the creature comforts that would transform all those new houses into homes.

“Within a few years, van Erp’s hobby had become a second source of income.”

Dirk van Erp was uniquely positioned to take advantage of the home-furnishings boom the earthquake inadvertently created. Considered today the leading Arts and Crafts coppersmith of the early 20th century, van Erp produced everything from coal buckets and fireplace sets to candlesticks, vases, and lamps, all hand-hammered in studios on both sides of San Francisco Bay. During his 25-year career, van Erp taught several generations of coppersmiths the tricks of the trade, helping to make the San Francisco Bay Area a center for copper objects and design.

Born in the Netherlands and raised in a family of coppersmiths, van Erp arrived in the United States in 1890 and settled in San Francisco around 1891. After a failed attempt at a plumbing business and an equally unsuccessful detour north to Alaska to try to cash in on the Klondike Gold Rush, in 1900 van Erp took a job as a coppersmith at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard near Vallejo, California, where he lived with his wife, Mary, and their daughter, Agatha. The couple’s son, William, was born there the following year.

Above: The Copper Shop in Oakland, California, circa 1909. Van Erp is on the right, with a young Harry Dixon second from left. Top: Two vases made from spent artillery shell casings. The one on the left has a “warty” surface.

By day, van Erp fabricated utilitarian pieces for the Navy, capitalizing on the skills he learned in the old country. But in his spare time, van Erp began hammering decorative vases out of spent artillery shell casings, which still bore the names of their manufacturers (“Winchester Repeating Arms Co.,” “UMC Co.,” etc.) on their bases. “He started off making those as his hobby,” says Gus Bostrom, who first became intrigued with van Erp as a pre-teenager. Since then, Bostrom has spent much of his life filling in the cracks of van Erp’s often incomplete history, using his shop, California Historical Design, in Berkeley, California, as a base of operations. “There was probably an area or department at the shipyard where he’d just pick them out of a bin and pay for them based on their scrap value.”

Naturally many of van Erp’s earliest forms were cylindrical, following the shape of his source materials. Some had modest, trumpet-like flares at their tops, while others had wavy, undulating openings. Surface treatments ranged from irregular grids of hammer marks to masses of “warty” bumps to columns of deep dimples. But soon the forms evolved to include wide, footed punch bowls and vases with gourd-like, bulbous bottoms. Within a few years, van Erp’s hobby had become a second source of income, as the blue-collar tradesman sold his handsome, decorative pieces through a prominent San Francisco art gallery.

In 1907, just one year after the quake, van Erp left the security of his job at the shipyard for the life of an artisan/craftsman. “Van Erp was not making Arts and Crafts shell casings right off the bat,” says Bostrom. “His first copper pieces were frilly, fussy, really Victorian-looking. Many had repoussé or chased designs on them. When people see these pieces today, they don’t have a clue they were done by Dirk van Erp, but he had only one style in the beginning, and that was Victorian.”

A copper log holder with with iron feet, by Dirk van Erp, from 1910-1913.

The reason, says Bostrom, is that van Erp was as much a product of his times as anyone else of that era. “He lived in a Victorian gingerbread house at the top of Ohio Street in Vallejo,” Bostrom says. “It wasn’t until, I would guess, after the earthquake, that Dirk van Erp started making what we think of as Arts and Crafts pieces.” Although Bostrom does not have any definitive evidence, he believes it’s likely van Erp took at least some direction from the retailers who were selling his copperware. “They were probably telling him, ‘This fancy stuff, it’s nicely done, we’ll take it. But make some of the more simple, plain pieces. That’s what people really want.’”

“That was my first inkling that somebody might be threatened by what I was trying to do.”

From an early age, Dirk van Erp was what Gus Bostrom wanted, too. “I just thought it was the coolest stuff in the world,” he says. “I remember being 12 or 13 years old and going into antiques shops in San Francisco and asking, ‘Do you have any of that Dirk van Erp copper?’ They didn’t laugh at me because it was already valuable back then. It seemed like everybody coveted things with the van Erp windmill stamped on the bottom.”

Bostrom’s biggest van Erp epiphany came in 1985, when a Sausalito, California, Arts and Crafts dealer named D.J. Puffert produced a show at Macy’s in San Francisco. “He took over half of the seventh floor,” Bostrom remembers, “filled with the best possible Arts and Crafts imaginable—Dirk van Erp lamps, Gustav Stickley director’s tables, a matched pair of Tiffany Wisteria lamps. I remember seeing a Rookwood vase that was maybe three feet tall with a snow scene of Indians walking through the wilderness. The quality was mind-boggling, and at that point I realized that one could make a career just selling Arts and Crafts, and I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

Harry St. John Dixon was one of the many coppersmiths who passed through the van Erp shop. This pair of Dixon vases and a candlestick are from around 1920.

Except he had to write a term paper for English class first. Naturally, the 10th grader chose Dirk van Erp as his subject. “At the time, there wasn’t anything written about van Erp except a couple paragraphs in ‘California Design 1910,’ which came out in 1974 for an exhibition in Pasadena. It was really the first show about the Arts and Crafts movement in California, but it talked very little about Dirk van Erp.”

As it turns out, some of the people Bostrom tried to interview didn’t want to talk about Dirk van Erp, either. “I went to one Arts and Crafts dealer and said, ‘I want to write a term paper on Dirk van Erp. Could you help me out?’ He looked at me, a 14-year-old, and replied, ‘Absolutely not. Why would I help you, kid, when I can buy $7,000 lamps for $1,000?’ That was my first inkling that somebody might be threatened by what I was trying to do. They didn’t want me to get too knowledgeable.”

But Bostrom got knowledgeable all the same, and as he learned more about van Erp, he realized that van Erp had influenced dozens of San Francisco Bay Area craftsmen, many of whom got their start hammering copper for the Dutchman.

Van Erp’s nephew August Tiesselinck is said to have influenced the design of this van Erp flat-top lamp, circa 1923.

One of van Erp’s first protégés was Harry St. John Dixon, not to be confused with Harry L. Dixon, another Bay Area coppersmith from the beginning of the 20th century. Dixon came to van Erp’s shop with little training, working for him from 1909 until 1911, when van Erp fired the young man. “Had it coming to me,” Dixon reportedly said. In fact, in a 1964 interview a few years before his death in 1967, Dixon had nothing but praise for his former boss and mentor: “I learned how to braze and how to draw the metal in, how to set it up; we made bowls, we made jars, we made large trays. Anything that came along.” Indeed, the experience was productive enough to land Dixon a job working for respected metalworker Lillian Palmer (described in a San Francisco Call headline from 1907 as “An Ingenious Girl Worker In Metals”). Dixon stayed with Palmer for six years before opening his own establishment in San Francisco in 1920.

“Surface treatments ranged from irregular grids of hammer marks to masses of warty bumps.”

Crossing paths with Dixon at both van Erp’s and Palmer’s copper shops was August Tiesselinck, van Erp’s nephew, who sailed from Rotterdam in 1911 to work with his uncle in America. Unlike Dixon, the youth arrived an accomplished metalsmith. In fact, Tiesselinck was hired away from van Erp by Palmer, who used his designs for the curvilinear shades in some of her lamps. By 1922, though, Tiesselinck was back at his uncle’s, making his mark on all sorts of van Erp pieces, including van Erp’s flat-top lamps.

Of course, two of the most important coppersmiths to pass through the van Erp shop were van Erp’s children. Agatha was teaching metalworking at the San Francisco Art Institute by the age of 18. When the United States entered World War I, Agatha and her brother, William, who at 16 was too young to enlist, kept the van Erp shop running while their father joined Dixon, Tiesselinck, and other tradesmen at the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, where they plied their skills in the service of the war effort.

Dirk van Erp, circa 1920.

Agatha may have gotten the earlier start in copper, but it was William who inherited the business after their parents died (within four hours of each other) in 1933. William made his mark on the business during the Great Depression by diversifying into metals such as brass and silver. He also pushed the firm into new stylistic realms, giving the green light to candlesticks, pitchers, and other pieces whose look was decidedly Art Deco.

After World War II, the dark, patinated surfaces of copper gave way to shinier things, as the clean lines of Mid-Century Modern elbowed aside styles like Arts and Crafts, which were deemed too old-fashioned and fusty. Today, though, many people are hungry again for the hand-hammered look of Arts and Crafts, which conveys an air of authenticity that can’t be found in the handsome if soulless offerings at Crate & Barrel and IKEA. For these people, Dirk van Erp’s work resonates strongly. Not only were his pieces handmade, he came by his aesthetic honestly, forced to prove himself in the rough-and-tumble world of blue-collar tradesmen before being embraced by the art-world elites.

The Copper King and His Court

(All photos courtesy Gus Bostrom, whose “Bay Area Copper 1900-1950, Dirk van Erp & His Influence” is a terrific overview of van Erp and his contemporaries. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

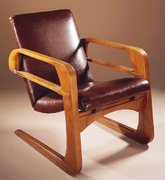

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Priceless Tiffany Collection Flees One Earthquake Zone, Lands in Another

Priceless Tiffany Collection Flees One Earthquake Zone, Lands in Another Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA Jewelry as Sculpture: The Birth of Modernist Studio Jewelry

Jewelry as Sculpture: The Birth of Modernist Studio Jewelry Copper CookwareFew activities are more basic than cooking, and few metals used in the prep…

Copper CookwareFew activities are more basic than cooking, and few metals used in the prep… Arts and Crafts EraThe Arts and Crafts movement that swept the United States and Great Britain…

Arts and Crafts EraThe Arts and Crafts movement that swept the United States and Great Britain… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fabulous article!

It is strange not to see any mention in this otherwise very informative post of the London and Chicago-trained D’Arcy Gaw, who was briefly van Erp’s business and creative partner circa 1910 and heavily influenced his turn towards the Arts & Crafts style. The earliest and best of the iconic “van Erp” mica-shaded, fat bellied lamps have her designer’s mark on them.

Dear reader, the picture of Dirk van Erp, with a cigar in his mouth , was found by me, in the legacy of my mother. This Dirk Van Erp was totally unknown to us in our family. It seems the brother of my mother ‘s grandfather . We have found that from 1882 to 1887 he has been in prison . He went to America and on October 6, 1890 he comes with three pieces of luggage, at the port of New York. He came back ones, to Holland in 1908. We are curieus if there are descendants of his life in the US Perhaps children Agatha and William ? Karleen Veenker

For Karleen: If you contact Isak Lindenauer antiques in San Francisco or California Historical Design in Berkeley, I am sure one of them could lead you to Van Erp’s grandchildren.

For 10 years my mother took private metal craft classes from, and was a friend of, Agatha Hooy. When I was recently in Maui, I visited the Baldwin arts and cultural center where I viewed the exact same silver designs, and assume they were made from another student of Mrs. Hooy’s.