Jorma Kaukonen, photographed recently by his wife of 30 years, Vanessa, via St. Martin’s Press.

“If you remember the ’60s, you weren’t there.” So goes the stoner cliché. Despite this paradoxical measure of authenticity, Jorma Kaukonen’s Been So Long: My Life and Music (St. Martin’s Press) is filled with richly detailed recollections of that landmark decade, although Kaukonen does confess to forgetting big chunks of the 1970s and ’80s. “That’s true,” the lead guitarist of Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna confirmed when we spoke recently about his memoir and memory lapses, “for better or worse.”

“We were in the right place at the right time and we made the most of our good fortune.”

For better, actually. Perhaps because of his awareness of his unreliable memory, Kaukonen describes people, places, and events of the ’60s mostly matter-of-factly. Here, for example, is Kaukonen on Monterey Pop: “One of the great moments for me was Otis Redding. This was also the first time I did cocaine. Owsley Stanley, the legendary audio engineer for the Grateful Dead, gave me a couple of lines and intimated that you got higher if you snorted it through a hundred-dollar bill.” On Woodstock: “I wish in retrospect that I had been stone cold sober so I could truly get a read on the event, but then it wouldn’t have been Woodstock.” On his ominous landing by helicopter at Altamont: “The chopper took off and showered us with dust.”

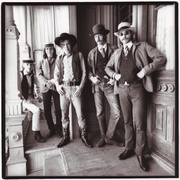

The classic lineup of Jefferson Airplane, circa 1967. From left to right: Grace Slick, Spencer Dryden, Jack Casady, Marty Balin, Paul Kantner, and Jorma Kaukonen. Photo via jeffersonairplane.com

Throughout the book, Kaukonen is equally honest and direct about his relationships with friends and especially family, who he says were probably “horrified” by certain aspects of the psychedelic scene in San Francisco. Ultimately, though, his parents and grandparents supported the notion that artists must express themselves, even if the artist in question was a son or grandson. Still, Kaukonen spends far more time on pointing out his failings than laying blame—Been So Long is short on settling scores, making it an outlier in the rock-star-autobiography genre. And lest you think that the book is all confessional and apologia, Kaukonen also regularly detours into the nerdy recollections of a certifiable gearhead, whether that gear is designed to produce music (guitars and amplifiers) or internal combustion (cars and motorcycles).

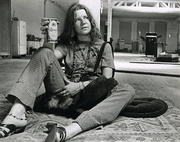

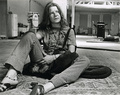

From Left to right, Jorma Kaukonen, Janis Joplin, and Steve Talbott at the Folk Theater in San Jose, California, 1962. Photo by Marjorie Alette, via St. Martin’s Press.

By now, some of you may be wondering, “Jorma who?” Well, even if you don’t know Jorma Kaukonen by name, you’re probably familiar with his work. That’s Kaukonen playing the vaguely flamenco-style electric-guitar solo at the beginning of “White Rabbit,” one of two Grace Slick hits on the Airplane’s second album, “Surrealistic Pillow,” that Kaukonen believes got the band into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. You may also be familiar with Kaukonen’s contemporaries. Along with Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, John Cipollina of Quicksilver Messenger Service, Barry Melton of Country Joe and the Fish, Mike Wilhelm of the Charlatans, and James Gurley of Big Brother and the Holding Company, Kaukonen defined the San Francisco Sound of the late 1960s, infusing the wail and feedback of a psychedelic electric-guitar with rhythms and riffs borrowed from the blues. In Hot Tuna, which continues to tour to this day, Kaukonen and Jefferson Airplane bassist, Jack Casady, threw their net of musical influences even wider, sounding like a traditional Americana string band on some albums, a distortion-heavy power-rock outfit on others, with a repertoire that included everything from traditional Christian spirituals to original Kaukonen compositions.

Most rock stars have unlikely origin stories, and Kaukonen is no exception. To put his journey in context, consider the case of one of his contemporaries, Janis Joplin, about whom Kaukonen writes, “The first time I met Janis, I realized that I was in the presence of greatness.” No disrespect, but it’s a safe bet Joplin was not thinking the same thing about Kaukonen when they performed together in 1962, with Steve Talbott on harmonica, at the Folk Theater in San Jose, California. Five years before her breakthrough with Big Brother and the Holding Company, Joplin was already a full-time musician at age 19, the product of a troubled childhood in the oil-refinery town of Port Arthur, Texas. A budding drug habit would round out the dues she’d eventually pay to sing the blues.

A self-described “Foreign Service brat,” Kaukonen (at left, in glasses) spent chunks of his childhood growing up in places like the Philippines. This photo from 1961 documents Kaukonen’s participation in the Christmas regatta at the Manila Boat Club. Photo via St. Martin’s Press.

In contrast, in 1962, Kaukonen was an indifferent student at a small, private, Jesuit university, still learning how to fingerpick, although he, too, was developing what would become an impressive drug habit, or several. Kaukonen’s parents, Jorma Sr. and Beatrice, were only a generation removed from Finland and Russia. Kaukonen himself grew up in Washington, D.C., the son of a diplomat whose career occasionally relocated the family to places like the Philippines and Pakistan, where servants waited on their every need. Kaukonen, in short, took the small stage at the Folk Theater as a bona-fide member of the privileged class, a self-described “Foreign Service brat”—the dues he’d pay would be entirely self-inflicted.

Kaukonen made his first down payment the summer after his gig with Joplin, when he joined his parents for his dad’s posting at the American Embassy in Sweden. By then, Kaukonen had met Jerry Garcia and other eventual members of the Grateful Dead, future Quicksilver Messenger Service founding member David Freiberg, and Paul Kantner, who, a few years later, would invite Kaukonen to join Jefferson Airplane. In 1963, Kaukonen, age 22, could have probably hung out and jammed with these musicians all summer long, but the pull of family was apparently still strong.

Kaukonen’s first wife, Lena Margareta Pettersson, was a frustrated artist, but she did create artwork for Hot Tuna’s first two albums released in 1970 and ’71 (left and center), as well as Kaukonen’s first solo album, “Quah” (right) from 1974.

As it turned out, the summer in Sweden included an excursion aboard a tourist ship from Stockholm to Helsinki and then on to Leningrad for a “roots trip” with his Jewish grandparents, Ben and Vera Levine, who had not been back to the old country since they left it for a better life in America at the turn of the 20th century. One of the passengers on that tourist ship was a 19-year-old Swede named Lena Margareta Pettersson, who shared Kaukonen’s fondness for drinking Johnnie Walker Black and playing cards. Their brief week-to-10 days together should have been a fun international fling. Then, on the last day of the tour, in Moscow’s Red Square no less, Kaukonen proposed marriage. By January of 1964, Margareta had joined Kaukonen in California. Shortly thereafter, the two were married in a 6-minute civic ceremony, which they celebrated with an evening of cheap wine, a nasty fight, and Kaukonen sleeping on the couch.

That cheery episode wasn’t even the first warning sign that their relationship was not going to be a bed of roses, but Kaukonen soldiered on, driven by the inertia of an impulsive decision he was unable to bring himself to undo. In fact, the aimlessness that pervaded their intensely stormy relationship would last 20 years, only stumbling to a clumsy close in 1984, by which time Margareta was a junkie and Kaukonen had taken to drinking during the day, a prelude to his own opiate addiction.

In addition to a love of music, Kaukonen has always had a passion for motorcycles. This shot of him on a favorite Harley in San Francisco was taken by Margareta Kaukonen, via St. Martin’s Press.

You can read Kaukonen’s book for more sordid details about the slow-motion train wreck that was their marriage, in which each gave as good as they got in their own destructive ways. For example, before they sold their house in San Francisco as a part of their divorce, the hole Margareta had punched in the kitchen wall, with the words “THE PRICE OF PASSION” written next to it, had to be repaired (“What a sense of humor!” Kaukonen exclaims in Been So Long). Beyond such colorful specifics, though, Kaukonen’s odd passivity and aversion to confrontation is one of the book’s major themes, applying not just to his relationships with people, but to the way he viewed his career as well.

Consider his behavior as the members of Jefferson Airplane were coming together in 1965. In Been So Long, Kaukonen paints himself as someone who was initially indifferent to the opportunity that had dropped into his lap, willing to do what was expected of him and happy not to be the one making too many of the decisions. When Paul Kantner suggested he get a Rickenbacker 12-string guitar because Roger McGuinn of the Byrds played one, Kaukonen, who already took his guitar choices very seriously, dutifully cashed in enough of the Israeli savings bonds his grandparents had given him and bought one. A few years later, when the band decided to use its burgeoning resources to buy a mansion off Golden Gate Park, Kaukonen didn’t think too hard about how his share of the band’s earnings was being spent. “There was some logic to this at the time,” he writes, “but I’m not sure what it was.”

Kaukonen first got to know Paul Butterfield’s lead guitarist, Mike Bloomfield, when the Airplane played several shows with “Butter and the boys” in the spring of 1966. Kaukonen credits Bloomfield with showing him how to play an “electric” guitar, rather than one that was merely “amplified.”

In particular, Kaukonen didn’t want any part of running the expanding Airplane empire that had grown out of the band’s success with “Surrealistic Pillow.” “With so much of the stuff that happened in my Jefferson Airplane life,” Kaukonen told me, “from starting Grunt Records to running the Carousel Ballroom, I went along with the guys who wanted to do it. But to be honest with you, the last thing in the world I was interested in was running a venue. I liked being able to walk in for free, but I didn’t want to make any business decisions.”

Later, in 1972, when the Airplane was barely able to keep itself aloft musically or financially, Kaukonen ghosted, quitting the band without so much as a goodbye. “I walked out of my life as a member of Jefferson Airplane as if it had never been,” he writes. Years later, he even pulled the same passive-aggressive stunt on Hot Tuna and his great friend Jack Casady, marveling in Been So Long that Casady was willing to forgive him, and thanking his maker that he did—the two friends continue to perform and teach together to this day.

Kaukonen met Jack Casady (right) when they were still kids in Washington, D.C. They played together in Jefferson Airplane before launching their own band, Hot Tuna, which continues to perform to this day. Photo © Barry Berenson, via St. Martin’s Press.

Still, it’s not like Kaukonen sleepwalked his way through life, especially in the Airplane’s early years. In the beginning, he remembers the group “rehearsing relentlessly” in an effort to be taken seriously by the critics. When the band’s early folk sound began to morph into something more electric, it was Kaukonen who recruited a childhood chum from D.C., the aforementioned Jack Casady, to become the group’s new bass player. Of course, Kaukonen does not pat himself on the back too hard for the band’s success. “You’ve got to fritter away a lot of time to get good at whatever it is that you do,” he writes with characteristic self-deprecation. “We frittered away a lot of time and got good at it.” Nor does he discount the importance of forces he could not anticipate and did not control. “We were in the right place at the right time and we made the most of our good fortune,” he concludes in Been So Long.

When Jefferson Airplane headlined this concert in Vancouver, B.C., in 1966, Kaukonen couldn’t believe that Muddy Waters was one of the opening acts. “It just didn’t seem right,” he writes in Been So Long.

One example of that good fortune says a lot about what it was like to be on the scene in the early days, before the hype surrounding 1967’s Summer of Love ruined everything. It occurred in the fall of 1966, when the Airplane played a number of shows, including the Monterey Jazz Festival, with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band from Chicago. The Airplane had already played with “Butter and the boys,” as Kaukonen calls them in his book, that spring. For several days that fall, Butterfield’s lead guitarist, Mike Bloomfield, and his wife, Susan, stayed at Kaukonen and Margareta’s place on Divisadero Street in San Francisco. At the time, Bloomfield was arguably the most important guitarist of the day. He had played the guitar solos on Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” in 1965, and was earning raves for co-writing the 13-minute, instrumental title track of the Butterfield Blues Band’s “East-West” album, which had just been released. Within a year, Bloomfield’s star would be eclipsed by Jimi Hendrix, but at the time, Mike Bloomfield was the big dog of the electric guitar.

“Mike took me under his wing and started to show me electric guitar tricks,” Kaukonen writes. “Up to this point, I still thought of myself as playing an ‘amplified’ guitar, as opposed to an ‘electric’ guitar and all the magic that goes along with that beast. He showed me how to bend strings in a pitch-specific way and many other techniques.”

By 1968, Kaukonen’s personal life was a mess, but his musical life was flying high, as seen by this “LIFE” magazine cover. That’s Kaukonen in the center cube.

As a fan of both guitarists, whose styles could not be more different, this struck me as one of the most intriguing revelations in Been So Long, so I asked Kaukonen to elaborate a bit more about his relationship with Bloomfield when we spoke over the phone. “I don’t mean to imply that Mike and I were longtime buds or that we hung out a lot,” Kaukonen began, “because we didn’t. However, his intersection in my life was fortuitous, and he was very gracious about seeing my potential and showing me what the electric guitar could do. I had listened to lots of Chicago blues because I loved the genre, but I’m a fingerpicking guitar player, so the style was alien to me. Mike showed me stuff that we all take for granted today, like sustaining notes by overdriving the amplifier—we didn’t have pedals for that back then—and ways to play certain kinds of licks. Those moments he spent with me were incredibly influential, and for that I’m eternally grateful.”

Kaukonen’s collection of tattoos includes this masterpiece on his back by Ed Hardy. Photo via St. Martin’s Press.

It was around this time that Jefferson Airplane began to hit the road more frequently. One trip to Vancouver, B.C., in November of 1966, marked the first time Kaukonen did not travel with Margareta. “Being away from my wife for the first time found me in a moral free-fall zone and I did not resist any of the temptations,” he writes. In other words, sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll! For Kaukonen, the most corrosive elements in that triumvirate were definitely the drugs. In particular, Kaukonen was finding his life increasingly dependent on the consumption of speed. Introduced to Dexedrine (which Kaukonen calls, “the Adderall of the time”) back in 1962 at that private Jesuit university, Kaukonen was now relying on prescription amphetamines to get him through performances. He considered speed a “working drug.” When Margareta got into it, too, their codependency did little for their already strained relationship. “The cold hard facts are that we were two tweakers living under the same roof,” he writes. “We circled each other like bodies in orbit, but we never touched. Did we have some good times? I guess so.”

For a brief period in 1968, the Airplane and Grateful Dead ran the Carousel Ballroom in San Francisco. This poster by Alton Kelley is an example of how that responsibility often meant the two bands would have to perform there to make ends meet.

Kaukonen’s substance abuse wreaked havoc on pretty much every aspect of his life, alienating him from the ones he loved and distancing him from his Jewish faith, which he has renewed in recent decades thanks to the encouragement of his wife of 30 years, Vanessa, who lives with Kaukonen and their daughter, Izze, at the Kaukonen family compound and music camp, Fur Peace Ranch, in southeast Ohio. For example, during much of 1967 and ’68, his band had a very close relationship with promoter Bill Graham, who booked the Airplane at the Fillmore and other venues and managed the group, too. Graham had famously escaped the Nazis as a child. Did Kaukonen ever find a moment to speak with him about that?

“We never did,” Kaukonen tells me with a sigh, “but he was good friends with my parents, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he had that conversation with them. I knew that he was a refugee from World War II, but sad to say, it’s a conversation I never had with him. And that’s my loss, because he was such an interesting guy. His strength as a human being, finding his way from Europe to the United States to become the Bill Graham we all knew … what an amazing man. I do remember, though, that when he made some money and bought a Mercedes Benz, he replaced the Mercedes hood ornament with a Star of David.”

Before Marty Balin (center) died in 2018, Kaukonen had a chance to rekindle his friendship with the singer. Grace Slick (left) wrote the foreword to Kaukonen’s book. Photo via jeffersonairplane.com

Less unresolved was his relationship with Marty Balin, who passed away earlier this year. Balin is credited with conceiving Jefferson Airplane (although Kaukonen gave the band its name), going so far as to open a club called the Matrix in 1965, essentially so his still-forming group would have a place to perform. When I spoke to Balin in 2017, though, the dissolution of Jefferson Airplane still grated. “When the Airplane became famous,” he told me, “everybody was pretty much into their own little ego, ‘I want to do my thing.’ Well, I always thought it was our thing, or the band thing.”

“Without Marty, the band would not have come into being,” Kaukonen told me when we spoke about Balin. “All of us will always owe him an enduring debt of gratitude—without him, there wouldn’t have been a Jefferson Airplane. Somebody asked me the other day for my favorite memory of Marty,” Kaukonen continues. “I told them that, honestly, my favorite memory is when he and I reconnected as friends when he played the Fur Peace Ranch in 2015. The Hot Tuna show at the Beacon Theatre in New York a few years back was also awesome. We were thrilled that we were able to give him that opportunity. I mean, he’s Marty Balin, for God’s sakes.”

Forgiveness is also one of the book’s major themes—of others, to be sure, but mostly of Jorma Kaukonen, although those are my words, not his. Naturally, Kaukonen puts it differently, offering a matter-of-fact corollary to this essential truth. “I’m an almost 80-year-old guy,” he tells me. “I’m a lot easier to get along with now than I was when I was in my 30s.”

In addition to being a memoir, Been So Long includes diary entries, song lyrics, and a CD of live performances.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

From Folk to Acid Rock, How Marty Balin Launched the San Francisco Music Scene

From Folk to Acid Rock, How Marty Balin Launched the San Francisco Music Scene Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties Behind the Scenes With Janis Joplin and Big Brother, Rehearsing for the Summer of Love

Behind the Scenes With Janis Joplin and Big Brother, Rehearsing for the Summer of Love RecordsMore than a digitally perfect CD, and way more than a compressed audio file…

RecordsMore than a digitally perfect CD, and way more than a compressed audio file… MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving…

MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

in ’72 at a show in William and Mary College, I crawled under the stage scaffolding and made my was to a seat on some sorta case back stage finding myself completely alone while airplane performed as I watched through the backdrop. when they came back before the first encoré I couldn’t muster a word to anyone even though I wanted so bad to speak to grace. after the last encoré I kept telling myself to say something!

I didn’t know it at the time it was the last encoré but, I managed a “HI” to grace, Paul, John, and papa John. barely a acknowledgement from anyone I almost grabbed jack who stopped to talk, I gave him praises about his playing. I didn’t know I could have told him I played drums and wanted to jam. I just figured they had a drummer, but, in hindsight, I could have possibly been assimilated in to the mix perhaps for the soon to come Starship of the mid to late 70s. wow! I blew it! but, I didnt know it. not till years later.

my point? I’d still love to jam drums & percussion with Jack & Jorma. I never stopped playing and would be honored to play with fellow DC-ites where I lived way too long. I’m in Orlando now but have a megshift poorly equipped studio where I write & play mostly for myself I guess just for the love of music. I can play some guitar but never thought of myself as a guitarist even though I have done some solo gigs on guitar. I actually have dedicated fans from the solo shows & with the bands I formed, “Phatto” and “8:59”. my writing is mishmash Ed because I have so many songs and melodies I write that my passion for “not wanting to lose an idea into the void” prevents me from finishing ideas I’ve started much in the same way. my “opposite of writers block” achieved the same results. nothing gets done.

so, still wanting to jam, Jorma or Jack give me a call. let’s jam. just like the old days.!

Only saw the Airplane once and that was at Woodstock, August 1969 ; they and Jimi hendrix were the reason I went there with my two best friends . It was five days of bliss for us ninteen year olds from the suburbs of Youngstown Ohio! Glad to this day that we went!

I am so glad at who you’ve become and I sure hope you remember me!

Another great article written by Ben Marks. Usually, I can’t read more than a paragraph but Mr. Marks mesmerizes with his incredible skills and storytelling. Saw the Airplane at the Fillmore East many times. My guess, they at times were a tad too stoned to be at their peak but always put on a great show. Jorma is right on with his review and compliment regarding Bill Graham. He escaped the Holocaust as a child and became one of the greatest of the greats gathering the best musicians of the sixties. Write a book, Ben, I’ll be the first to buy.

I lived a floor below Margareta from 1981 to 1984 when she lived on Taylor street and shared an apartment with her friend Tanya. She lived in an SRO when she died in 1997 and she was not a junkie by then, she was an alcoholic. I know this for a fact.

Cool

Jorma and Jack like peas and carrots, classic and super talented ….. on my bucket list

How is Matthew Katz left out of this story?

So happy I had the chance to see Hot Tuna play live several times!!!

Me too!

Jorma’s Tattoo was done by Bob Roberts not Ed Hardy

I saw Jorma with the Airplane at Altamont. I remember Grace saying something to the effect “the Angels just beat up my guitar player” disgustedly and standing her ground. Jorma is a great musician.