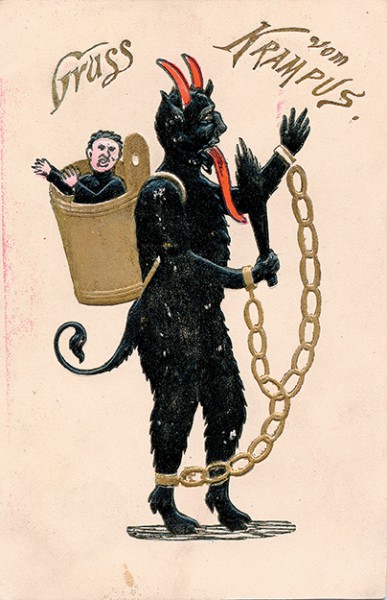

You’ve heard the rumor that Santa Claus will leave a lump of coal, possibly some switches, for children who rank on his “naughty” list. But did you know that before the 20th century, old Saint Nick—that is, the European St. Nikolaus—had a devil sidekick do his dirty work? Krampus, a furry, horned, cloven-hooved creature with a disturbingly long tongue, was in charge of filling boots with spanking switches. And if children were really bad, he’d throw them in a wheelbarrow or in a wooden basket carried on his back, or cuff them to a long chain, and haul the little brats off to torture them.

“Krampus is like the bogeyman. He was created by adults to scare the bejeezus out of wayward children.”

During the Golden Era of Postcards (between 1898 and 1914), creepy Krampus was a particularly popular subject for holiday cards in Eastern Europe, as a reminder for children to remain on their best behavior. But the “Christmas devil” never took hold the same way in the United States, where the slender, severe-looking St. Nikolaus became the joyful, jiggly Santa Claus, who was helped by adorable elves and reindeer. Then in 2004, BLAB! magazine founder and illustrator Monte Beauchamp published a book of early 1900s Krampus postcards, which sparked a new fascination with the beast in America. We asked Beauchamp to explain to us exactly what this bizarre man-beast has to do with having a holly jolly Christmas anyway.

Collectors Weekly: How did you get interested in Krampus?

Monte Beauchamp: An acquaintance of mine was an aficionado of vintage postcards. Out of the myriad of categories he collected, the postcards that grabbed me the most were of a European Christmas character called Krampus. The examples he had were all pre-World War I and printed by an intricate technique known as chromolithography, an offshoot of lithography. Their artistry and craftsmanship were superb.

The artwork was so masterful, I thought they’d make for a great feature in BLAB!—an anthology of lowbrow art, illustration, vintage graphics, and cartoons that I edit, art direct, and produce. The response was so enthusiastic, I decided to run a follow-up feature in the next issue (BLAB! #12), and from there I managed to interest the publisher of BLAB! to produce a softcover collection titled The Devil in Design: The Krampus Postcards. The printing quality and binding of that edition was subpar, so several years later I released a much superior, hardcover edition titled Krampus: The Devil of Christmas, published by Last Gasp. That’s how the ball got rolling.

Collectors Weekly: Who is Krampus?

Beauchamp: He is St. Nikolaus’ companion. In America, Santa Claus has elves; whereas in Europe, St. Nikolaus—from which Santa was derived—has Krampus. Nikolaus would bring treats and small gifts for the children who’d been good all year, and those that had behaved badly were visited by Krampus.

Krampus rose out of the European Christmas tradition of which there are several other unsavory Krampus-type characters. Among the better known are Knecht Ruprecht, who would cram juvenile delinquents into a large cloth sack and haul them around town on his shoulder. The Dutch have Zwarte Piet (Black Peter)—a dark-faced menace in medieval attire who would stuff misbehavers into a bag and haul them off to Spain. In Czechoslovakia, children who were unable to recite their prayers to St. Nik were beaten by an evil spirit called Cert. Yet, by and far, the most frightening of all was Krampus.

Collectors Weekly: Why was Krampus so scary?

Beauchamp: He’s like the bogeyman and was created by adults to scare the bejeezus out of wayward children. Every country seems to have their own bogeyman. On December 6, which is St. Nikolaus Day, obedient children would hop out of bed and rush to the empty shoe they’d placed outside the night before to retrieve the small gifts or treats that St. Nikolaus had left for them. In the shoes of disobedient children awaited switches, with which their parents would spank them. Those that had been especially bad were paid a visit by Krampus, who oftentimes would place them in the wooden basket strapped across his back and cart them off to the countryside and terrorize them until they promised to be good.

Collectors Weekly: Is Krampus the devil?

Beauchamp: Though Krampus is perceived as a devil and is referred to as one, he’s mainly a composite of man and beast; he has fur all over his body, and what devil has a tongue like that? He’s also a good-natured character; his only desire is to persuade unruly children to turn from their wicked ways.

Collectors Weekly: Was early Santa Claus both St. Nicholas and Krampus rolled up into one?

Beauchamp: No; they’re separate. Santa Claus is a jolly, roly-poly type character brought to this country in the early 1800s. Contrary to popular belief, Santa was never an American original but a watered-down version of Europe’s more austere St. Nikolaus, who was lean and tall. Perhaps because of what happened in Salem, America wanted nothing to do with a Christmas character that resembled a devil and left Krampus behind.

Collectors Weekly: Did children ever get revenge on Krampus?

Beauchamp: In the original Christmas tradition, no kid ever got revenge on the Krampus. Here in America, some people are attempting to portray Krampus in the worst possible light. For example, there’s a new horror book out in which Krampus is portrayed as a murderous beast out to kill Santa Claus. It’s really sad. This isn’t Krampus, but a total misrepresentation of the character.

Collectors Weekly: Who produced Krampus cards in the postcard era, and where did you find them?

Beauchamp: The Golden Age of the European postcard era began in the late 1890s, thanks to the development of a color-printing technique termed chromolithography. This technique inspired and enabled postcard artists and craftsmen to produce cards that just so happened to captivate the public.

“Children who had been especially bad were paid a visit by Krampus, who’d cart them off and terrorize them.”

The top-selling categories were always the holiday cards, of which Christmas proved to be the most popular, especially those of the Krampus. The earliest Krampus card I know of is dated 1898, but after two world wars, all the key postcard publishing houses in Europe were destroyed, so no records exist as to which artists drew what. Not only was all of the original art destroyed, millions of cards were burned to a crisp. This is why many of the early Krampus cards are extremely rare and some impossible to find. Very rarely did artists sign their work; most of them worked anonymously. After the First World War, the quality and content of Krampus cards sank dramatically.

Collectors Weekly: When and why did he disappear from Christmas pop culture?

Beauchamp: He’s didn’t disappear from European Christmas culture but did fade a bit in popularity. But here in America, where Krampus has recently been introduced, he is gaining in popularity.

Collectors Weekly: Is Krampus supposed to be sexy? How is it that this strange creature is shown seducing ladies?

Beauchamp: There’s really no relationship of any of this to the original European tradition. Krampus was for kids. About 60 years after the original Christmas postcards appeared, a series was released of Krampus as a Hugh Hefner Playboy-type character hanging out with sexy girls, but in the realm of postcard collecting, these are considered trash. Yet, now that Krampus has come to America all sorts of interpretations are beginning to pop up.

Collectors Weekly: What date does Krampusnacht take place? How do you celebrate?

Beauchamp: On the Eve of St. Nikolaus, which is December 5, in Salzburg, Austria there’s a winter festival known as Krampuslauf—“The Running of the Krampus,” in which young men clad in Krampus costumes are herded into town by a person attired as St. Nikolaus. He then greets the crowd and unleashes the herd of Krampuses, who rattle chains, clang cowbells, brandish birch switches, and terrify the children.

Collectors Weekly: Do you know anything about the Krampus wooden mask-making tradition in Austria? Looks like the stuff of nightmares.

Beauchamp: The early, original wooden masks are referred to as larven, and they were hand-carved by local craftsmen. The horns were either those of a chamois, goat, or ibex, and the fur-covered costumes were made of animal hide.

Collectors Weekly: Have there ever been backlashes against these parties?

Beauchamp: Back in the ’60s, some teenagers dressed up in Krampus costumes and went around beating up old people, so in, I believe it was southern Germany, Krampus was outlawed.

Keep in mind, Krampus was always a kid’s thing; as with many of the early European children’s books such as Struwwelpeter, Krampus is a cautionary tale so parents could teach their children that there are consequences for bad behavior.

Collectors Weekly: Where has Krampus been popping up in modern pop culture?

Beauchamp: Outside of the several books I produced about the character, there’s not a whole lot. As to why Americans seem interested in Krampus? Some seem to enjoy the imagery on the early postcards; others seem to dig the fact that a wholesome character such as Santa is actually derived from Europe’s St. Nikolaus, who once traveled with a character that resembled the devil. That seems to be America’s main fascination with Krampus.

For more Krampus postcards, you can find Monte Beauchamp’s “Krampus: The Devil of Christmas” at Last Gasp Books.

The Charms of Christmas Ephemera and the Changing Face of Santa Claus

The Charms of Christmas Ephemera and the Changing Face of Santa Claus

Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up?

Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up? The Charms of Christmas Ephemera and the Changing Face of Santa Claus

The Charms of Christmas Ephemera and the Changing Face of Santa Claus Hellfire and Damnation in Your Back Pocket

Hellfire and Damnation in Your Back Pocket Christmas PostcardsIn 1843, a wealthy British man named Sir Henry Cole had so many greetings t…

Christmas PostcardsIn 1843, a wealthy British man named Sir Henry Cole had so many greetings t… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Wow, nostalgic article Lisa. I grew up in Wiesendorf, Germany, as a child my father would scare my brother & I with the tales of Herr Braun/Krampus (Mr. Brown). We didn’t get out of line much being in fear of being taken away. LoL

Great article Lisa, Happy Holidays & Merry New Year! =)

There’s little difference between Krampus and Satan….between Santa and god…

All are created to control the masses…