There’s plenty to hate about driving—traffic jams, car accidents, speeding tickets—not to mention the endless headache of finding a spot to park. So what if you discovered an invention that could wean us from our vehicles, combating suburban sprawl and making city streets less dangerous, congested, and polluted? Well, that device has been around for nearly 80 years: It’s called the parking meter.

Contrary to popular belief, the parking meter was originally designed to keep traffic moving and make more spaces available for shoppers, a measure often lauded by local businesses as much as the public who paid their hourly rates. Beginning with the first parking meter, installed in 1935 on the corner of First Street and Robinson Avenue in Oklahoma City, and spreading clear across the United States, the device was hailed as the great solution to our parking woes. Yet decades of poor meter implementation, inane off-street parking requirements, and technological stasis slowly turned our city streets into a driver’s nightmare.

“People who walk, bike, or take transit are bankrolling those who drive.”

In the early 20th century, the United States rushed to embrace the independence and flexibility offered by motor vehicles, ignoring thousands of years of urban design in favor of the fast, cheap mobility automobiles provided. American towns were built to accommodate cars, rather than integrate them.

“The idea in force in American law at the start of the 20th century, that thoroughfares were for the movement of traffic—with certain specific exceptions such as the loading and unloading of goods and passengers—gave way fairly quickly to the idea that took root in the popular mind that parking of vehicles on the street was a right and not a privilege,” writes Kerry Segrave in “Parking Cars in America, 1910-1945.” In response, ill-conceived regulations helped cement the concept of free parking as a public good across America, fueling our dependence on automobiles.

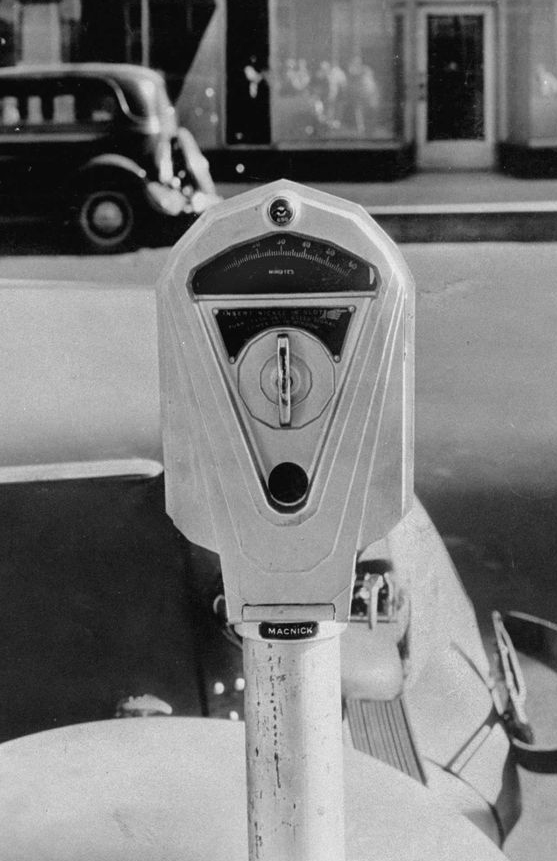

Top: A forlorn driver in a Los Angeles parking lot, circa 1955. Image via the Los Angeles Public Library. Above: A classic “Park-O-Meter” made by Magee-Hale in Bellaire, Ohio in 2011. Photo courtesy scottamus’s flickr stream.

Segrave notes that by 1920, city traffic jams were commonplace due to bountiful free parking without legal restrictions to encourage turnover. Street parking spaces were typically occupied by commuting workers, leading to snail-paced traffic and frequent double-parking as daytime drivers fought for the few spaces vacated during business hours. In many urban centers, more street space was filled with parked cars than moving ones. Unfortunately, most city leaders didn’t turn to mass transit as a solution to increased congestion, and actually used gridlock on downtown streets, frequently due to street parking, as an excuse to tear up efficient commuter tracks and inner-city rail systems.

The most visible instance of such degradation was the General Motors streetcar scandal: Beginning in the late 1930s, several automobile-related businesses, including GM, Firestone, and Standard Oil, created front companies to purchase and dismantle rail-based transit systems, especially inner city tramways, and replace them with less efficient bus lines. In 1949, the companies would be convicted of a conspiracy to monopolize transportation, but the damage was already done.

Left: In the 1930s, Parker Brothers’ earliest “Monopoly” sets already included the requisite space for free parking. Right: During the 1920s, an absence of restrictions meant that the majority of American city streets were devoted to free parking, rather than the flow of moving vehicles.

In fact, automobile congestion had been a problem since the late 1910s, so much so that several cities, including Los Angeles, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia, passed laws completely outlawing street parking in their central business districts. However, public protest and pressure from local businesses soon overturned such bans in favor of restricted time limits on downtown streets. Yet enforcement was still inadequate, as police departments typically used a poor system of patrolling streets on foot and marking tires with chalk to indicate the time parked.

Then, in July of 1935, a novel technological effort to improve parking turnover was initiated in Oklahoma City, where entrepreneurs Carl Magee and Gerald Hale designed the world’s first parking meter, ominously dubbed “The Black Maria.” Using a coin-operated timing system, their meters displayed a red flag once payment had expired, making parking laws much easier to enforce. As a trial, the Magee-Hale “Park-O-Meter” Company installed 200 machines along a 14-block stretch of downtown, divided into 20-foot spaces. They agreed to place meters on one side of the streets at no charge to the city with the understanding that their initial capital cost would be repaid by the five-cent hourly rate, after which the city would reap all parking fees.

On their first day of operation, motorists tentatively adopted the new meter technology, but by the end of the first week, shops fronting parking meters reported increased sales, prompting establishments on the opposite side of the street to beg the city for their own magical meters. The following year, a New Republic editorial praised the device’s effectiveness, calling it “the next great American gadget.”

As the New Republic explained, the mechanism had “already spread to Texas, Florida and Michigan and seems likely to sweep the country.” In addition to benefitting city treasuries and increasing parking turnover, the article claimed few motorists opposed the device, and many “warmly approve it.” Though there was some backlash from drivers who accused municipalities of charging a new tax on roads, a publicly owned property, cities successfully defended meter fees in court as a way to fund parking regulation and enforcement.

Residents watch with excitement and trepidation as the first meters are inaugurated in Washington, DC, in 1938. Photo courtesy Roth Hall.

During the late 1930s, to serve the growing demand for parking meters, several new companies followed Magee-Hale’s lead, like M.H. Rhodes’ Mark-Time meters and the Duncan-Miller Company. In 1938, American City magazine reported that 85 municipal areas had installed new meters, and Segrave says, “those cities were practically unanimous in praising the machines and what they had done in solving their cities’ parking problems.”

“Cities were practically unanimous in praising the machines and how they’d solved their parking problems.”

Meanwhile, local governments began establishing off-street parking requirements for new buildings in a further attempt to eradicate traffic jams and force developers to accommodate private motor vehicles. A 1946 survey of 76 cities found that only 17 percent had parking requirements in their zoning ordinances, but only five years later, 71 percent had off-street requirements or were in the process of adopting them. Thus began the great American sprawl: Since most new construction was required by law to include a minimum number of parking spaces, gigantic parking lots and hulking city garages grew like tumors from city streets.

In his definitive book, “The High Cost of Free Parking,” Donald Shoup explains that minimum parking requirements “led planners and developers to think that parking is a problem only when there isn’t enough of it. But too much parking is also a problem—it wastes money, degrades urban design, increases impervious surface area, and encourages overuse of cars.” Besides the fact that legally required lots are often more than half-empty, they result in a variety of negative impacts, from environmental runoff issues to inhospitable pedestrian zones. Instead of using the tools available to limit automobile use and encourage free-flowing street traffic, Shoup explains that planners traditionally did the opposite, requiring “enough off-street spaces to satisfy the peak demand for free parking.”

Additionally, such ordinances falsely reduced the explicit cost of city driving, transferring the true expense of so-called “free” parking to every citizen in the vicinity, diffused into taxes, real estate, product, and service fees. In effect, this legislation created an environment where “nobody can opt out of paying for parking,” says Jeff Speck, renowned urban planner and author of the book, “Walkable Cities.”

According to Speck, “people who walk, bike, or take transit are bankrolling those who drive. In so doing, they are making driving cheaper and thus more prevalent, which in turn undermines the quality of walking, biking, and taking transit.” Furthermore, our plethora of free parking resulted in a range of negative consequences still unaccounted for: “The social costs of not charging for curb parking—traffic congestion, air pollution, accidents, wasted time, and wasted fuel—are enormous,” writes Shoup.

By 1950, as a concession to the automobile’s omnipresence, parking meters had spread to most urban centers in the United States. An article in The Rotarian claimed that “most motorists like the parking-meter idea, for they find curb parking spaces more easily in metered districts. Merchants say that this easier parking improves their business.” The story also highlighted the great return cities had seen from parking revenue, which was used to pay regulatory policemen or trendy new meter-maids and also to expand off-street parking. For the next fifty years, the U.S. used its parking meters in almost exactly the same way.

By the 1950s, parking regulations were much easier to enforce thanks to the nifty new meters. Photo courtesy Roth Hall.

Meanwhile, in Europe, where cities were predominately built without the car in mind, meters continued evolving to curb the negative impacts of private vehicles. “Although the parking meter was invented in the U.S.,” says Shoup, “most of the subsequent technological progress has been made in Europe, where the scarcity of parking creates a demand for more efficient and convenient metering.”

European cities have been quicker to adopt modern payment methods, such as credit cards linked to mobile phone applications or license plate numbers. Furthermore, their planners recognize the power of parking to manipulate driving habits: A 2011 report called “Europe’s Parking U-Turn” by Michael Kodransky and Gabrielle Hermann states that “every car trip begins and ends in a parking space, so parking regulation is one of the best ways to regulate car use.”

“Most motorists like the parking meter idea, for they find curb parking spaces more easily.”

Today, parking covers more of urban America than any other single-use space, yet the vast majority of meters are outdated, coin-only devices, charging a flat-rate during operating hours across all zones. “From the user’s point of view, most American parking meters remain identical to the original 1935 model,” writes Shoup. “You put coins in the meter to buy a specific amount of time, and you risk getting a ticket if you don’t return before your time expires. The main change in 70 years is that few meters now take nickels. In real terms, however, the price of most curb parking hasn’t increased; adjusted for inflation, 5 cents in 1935 was worth 65 cents in 2004, less than the price of parking for an hour at many meters in 2004.” Once praised as the answer to our auto problems, the invention has languished on American sidewalks. (POM, Inc., the descendant of the Magee-Hale company, is still producing standard meter designs, albeit with digital LCD screens and credit card payment modules.)

Studies show that under-priced meters have created a false sense of scarcity for drivers, who instead spend more time and gas circling the block than if they parked off-street in a free garage and walked to their destination. “The goal, of course, is to price both on-street and off-street parking in a carefully strategized way that results in cars being where you want them, when you want them, and keeps a 15 percent vacancy along the curb as Shoup recommends,” says Speck. “The parking meter and the price of parking is a tremendously powerful tool that cities can use to see their downtowns thrive.”

Shoup boils his recommendations down to three basic solutions to the parking disaster: Charge fair market prices for on-street parking, dedicate meter revenue toward public improvements on metered streets, and remove off-street parking requirements. “I think that more and more planners are beginning to realize that what they were saying as a routine thing was dangerous nonsense,” adds Shoup.

Since Shoup’s book was published in 2005, many major cities like New York, Chicago, Seattle, and Denver have begun the transition to modern meters that accept all kinds of payment, but ground zero for the U.S. parking revolution is San Francisco, one of the country’s most pedestrian-friendly cities. In 2011, the City of San Francisco instituted the groundbreaking SFpark program, outfitting certain neighborhoods with advanced meters and parking sensors whose rates can be programmed based on vehicle occupancy and turnover (Duncan Industries, originally called Duncan-Miller and one of the earliest meter manufacturers, is responsible for a portion of San Francisco’s new devices). The program also includes a free mobile phone app that helps drivers locate available spots, identify meter rates, and make payments.

Since the project’s debut, meter rates have been adjusted every six weeks to reach an optimal hourly charge that will keep between most meters occupied with a few always open for new vehicles. Recently, the San Francisco Examiner found the project to be an overall success, with parking rates and fines actually decreasing across the city even as spaces become more available.

A rendering of the new individual and multi-space machines installed for the SFpark program.

Though San Francisco is not the norm, Donald Shoup is hopeful about the results of parking meter experiments in smaller cities like Ventura, California, which installed an updated meter system in 2010 to allow for credit-card payments and improved meter pricing. Ventura offers a stellar example of what Shoup calls a “parking benefit district,” or a neighborhood that institutes updated parking policies, and in return spends its parking revenue on neighborhood improvements. As a result of its meter upgrades, the city was able to pay for street improvements and provide free wi-fi across its central business district, not to mention hiring parking-enforcement officers whose presence has helped reduce crime rates up to 40 percent.

“Parking reform is such a terrific opportunity for improving city life,” says Speck. “It’s something quite small that can be done on a single block; it’s very incremental. All the data is there. You just need to open your eyes.”

When the Wild Imagination of Dr. Seuss Fueled Big Oil

When the Wild Imagination of Dr. Seuss Fueled Big Oil

This 1959 Goggomobil Is Insanely Cute and Gets 55 MPG. Why Can’t Detroit Do That?

This 1959 Goggomobil Is Insanely Cute and Gets 55 MPG. Why Can’t Detroit Do That? When the Wild Imagination of Dr. Seuss Fueled Big Oil

When the Wild Imagination of Dr. Seuss Fueled Big Oil Murder Machines: Why Cars Will Kill 30,000 Americans This Year

Murder Machines: Why Cars Will Kill 30,000 Americans This Year Parking MetersLike death and taxes, parking meters seem like the sorts of objects that ha…

Parking MetersLike death and taxes, parking meters seem like the sorts of objects that ha… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

parking meters are illegal in public places in the state of North Dakota.

What an excellent article. Although I have many times cursed these items in places I wished to park, I now have a new found respect for them. I agree that without them some people would use them to park and go to work oblivious of the need to keep them free for others to shop with the merchants. Thank you for this article and helping me to see these old items in a new light!

“found the project to be an overall success, with parking rates and fines actually decreasing across the city”…what makes you think cities want parking fines to decrease. See red light (s)cams.

Living near Ventura I have greatly reduced my visits downtown since the meters went in. The nuisance of working the parking payment system or trying too find parking elsewhere is not worth time spent for such a short trip so I shop elsewhere where its easier. Now lots of weekenders do come up from Los Angeles and since they drive for a couple of hours and they want to see downtown, the time they take to pay for parking is a small percentage of the time they spend driving.

Net effect is downtown is for tourists and locals go elsewhere. There were promises that the proceeds would go to safety and the homeless problem but of course those issues are as bad as they ever were.

There are a lot of holes in this argument. It would seem history has proven the parking meter has not solved anything, only made people angry and look for somewhere else to park. The author makes a very interesting observation about the actions of car companies to corner the transit market. It’s very unfortunate how that has effected mass transit options. The truth is that urban planners and designers could curb parking issues with better design and not simply installing more meters at higher rates. That is only one option, and the only one presented here. Seems a little weak. Also the whole system focuses on a less effective incentive model. People just look for other options or don’t shop there. I have never met anyone that was happy to pay at a meter so that they could keep the streets clearer. I have however, seen tons of opens meter spots because no one wants to pay to park. This article takes a lot of twists and turns, some of which I find useful and others not at all. Meters = fail.

Minority opinion:

“But too much parking is also a problem—it wastes money, degrades urban design, increases impervious surface area, and encourages overuse of cars.”

The impervious surface area part may make some abstract sense, but the rest of it is just hogwash. I LONG for the decent parking lots of yore, for ENOUGH parking, for enough slots to park away from other cars, rather than in the mini-slots this kind of social engineering demands.

I won’t patronize any businesses with parking meters around them. Instead, I go to large retail stores like Walmart, where there is ample free parking.

To think parking meters in this day and age with increase business is foolishly out of touch, and ignores the brutal reality of competition… there are plenty of more attractive competitors out there that offer free parking without a second thought to boot. Downtown businesses can’t compete with Walmart, Kmart, Roses, Malls, or other large retail superstores, even if they did have free parking… installing parking meters only puts a final nail in their coffin.

It’s funny when your municipality complains that the meters don’t make any money but keep hiring people to service them. Posted revenue from meters and parking fines would clearly indicate profit but they keep telling me that they are barely able to pay the department. Sounds like either BS or they are getting fleeced by the manufacturers of the meter equipment. All in all it doesn’t do anything but disrupt the day for numbers of people that have to work and live in the downtown area. Workers will set alarms to run out and plug the meters and use the spot all day anyway. Dumb idea.

Placing parking meters downtown just drives people to malls and shopping centers where parking is free. Thus driving privately owned businesses out of bussiness. Wallmart, Target, and Malls LOVE the idea of parking meters on city streets.

Randy…sorry, but he FACTS don’t back you up. As they said…when parking meters were installed, business INCREASED.

“So what if you discovered an invention that could wean us from our vehicles, combating suburban sprawl and making city streets less dangerous, congested, and polluted?”

The bicycle.

At the same time, there is a pretty big problem in san francisco for locals who live there. San Francisco’s transit system MUNI is pretty bad.

If San Francisco could improve MUNI a lot more people would not need to have a car to get around the city.

The problem is threefold and easy to see, as long as you don’t try to shoehorn the issue into conforming to your own personal philosophy, as is evidently the case with this biased article. The blind disregard it has for any factually based conclusions is amazing.

#1. The vast majority of Americans always prefer their own means of transportation over public transit, which is (#2) grossly inefficient, inconvenient, and corrupt, just like the (#3) parking authorities in most cities.

Cut down on the government control in this area, which is in practice nothing but a money based form of nepotism and civil corruption. Decrease government’s stranglehold, give the majority of people what they want and they will come, instead of trying to force the unique American character into the obviously failed model of European social engineering.p

“parking meters are illegal in public places in the state of North Dakota.”

Not at all relevant. North Dakota has no people, thus no need for any kind of real parking regulation or enforcement.

Places with millions of people on the other hand, absolutely require it. My neighborhood alone has more people than North Dakota’s largest city.

Clearly, as the comments here show, people are unwilling to consider the consequences of their actions when it comes to cars and parking. The mentality is very much – “gas should be cheap and parking should be free. Everyone else pays for the negative externalities, not me.” It is this attitude that will destroy civilization, utterly and completely. History will not excuse our poor choices.

It’s all about nickel-and-diming you to death.

Pfwew, it’s apparent from the comments just how out of touch most Americans are when it comes to sustainable city design. Malls are dead, big box stores have a bad reputation, younger people are driving less, urban living is the thing to do. Sprawl is over, and with it, free parking is dying. Sprawl will never come back either, considering the sting it left us with the financial crisis.

What we have to look forward to now is the decay of our suburbs and the social issues of rapid gentrification.

Parking is going to be a moot point once driverless cars catch on. Other than vintage collectors, individuals will not own cars, instead signing up for auto service like zipcar which will send a ride wherever they need it. Upon arrival the car will not stay parked except by special request – if the passenger does not want to leave anything in the vehicle it will take off to service the next customer. There will be more than enough parking for those who choose to drive themselves.

Why are even these San Francisco parking meters so blinkered in 1930’s imagination? Why can’t they tell my phone (or my car) where the nearest available spaces are so I don’t have to drive around searching for it?! This reduces congestion, and suddenly meters (and meter payments) are my friend instead of my enemy because they are offering me a visible service that I need. The same system could also tell meter enforcement where the overstaying vechicles are, so instead of spending hours wandering around checking vehicles, they’re guided directly to spots in need of parking tickets. Fewer enforcement staff required, the city saves $$$.

Everybody wins, if we can break out of the 1930s model.

I’m odd. I believe nothing should be free, but also that no one should need to earn money, at least up to a point. Meter everything, there will be a tendency not to waste and to prioritize, plus it tends to focus attention on where improvement would make people happier and earn rewards. For example, if people got charged for impacting the climate, and could offer to pay for the climate they preferred, chances are there would be a rational pattern evolving, not a blind rush off a cliff. Then just grab a fee (VAT tax) out of all transactions, allocate it to a gradually disappearing subsidy so that all people had whatever was deemed to be enough money to have enough choices so as to live in dignity, and also so that the VAT rate was thought to be affordable, leaving room for incentives and investment.

Applied to parking, a poor person might receive an outright transportation subsidy, applicable to ANY transportation expense. Scarce parking would be just that; people would go elsewhere or go by other means, or pay a stiff fee if it really was their priority, and no one would worry about parking: when non-existent parking became profitable enough for it to be built, it would have PROVEN to be more valuable than whatever it was replacing. No more demolition of the priceless to make way for a parking lot – both would have prices.

The main purpose of this article is to show how evil cars are and to load parking meters as the means to wean, etc…

Someone even suggested bicycle as an effective solution.

I think, the solution is to have an efficient, fast and ubiquitous public transportation. When it is non-existent or when you have to wait for the next bus for 30 min in the cold, this is when people have to use cars. Until public transportation becomes more convenient to people than driving, nothing will change.

Introducing more meters and raising prices does not do any good except discouraging people to drive downtown at all. The example is our fine city of Chicago that introduced parking meters that cost 2-3 dollars per hour, and the price will be climbing higher. These meters are covering the entire city, not just downtown, even places on a quiet side streets where there were not any meters earlier. If discouraging driving into the city is the main idea, then just say it (“we don’t need you stinking suburbanites in our beatiful towns”) And I can’t imagine any city businesses reporting increased income in the situation when it is made unpleasant to drive (and park) near their stores and restaurants

So, to summarize, RJ. EVERYBODY is completely out of step. Or, as Yogi Berra is claimed to have said, “Nobody goes there anymore because it is so crowded.” I fear you have left out a couple of other important observations such as everybody knows that stores don’t need to be open on Sunday afternoons because everybody is playing polo then, and if everyone was just like me everything would be all right.

I wish there had been a citation for the information regarding the 1949 anti-monopoly conviction against General Motors et al (could the author point us towards his sources?).

I also noticed several comments disparaging efforts by municipalities to manipulate parking behavior and generate revenue, but almost none have remarked on so-called Big Business engaging in that kind of social engineering (going so far as to create an entirely new geography of automobile parking, including technical and physical infrastructure, incentives, customs, rules, etc). As long as we continue to allow corporate and oligopolistic interests to dictate the terms of how we structure society, then perhaps it is safe to say that the next urban landscapes will also arise from such interests.

Hi Nicholas,

Here’s one article (among many) recounting the General Motors Streetcar Scandal: http://www.intransitionmag.org/archive_stories/streetcar_scandal.aspx

The worst part is that the court only imposed a $5000 sanction on GM, and fined H.C. Grossman, the company treasurer who led the operation of the front company “Pacific City Lines,” just $1. (see more details here – http://www.worldcarfree.net/resources/freesources/American.htm)

thanks for reading!

Hunter

Black Maria?! Love the new meters where I have an account and charges cease when I return to my car. This will never discourage me from local businesses and no amount of free parking will get me to Walmart. Great article!

@Justin as a SF resident I can confirm the SFPark meters do have everything you’re talking about. There is an app that piggybacks on the meter system. It shows you a map of parking in the area with streets designated with green, yellow or red levels of parking availability. It also allows you to pay through the app, on a website, or over the phone so you don’t have to go back outside to feed the meter or check how much time is left on it. It even sends you a text message when your meter is running low to remind you to add more time.

They also have a changing meter rate during peak parking hours and based on the number of spots taken/available. It will charge as little as $0.25/hr all the way up to $5/hr in an effort to turn over spaces when they are needed the most.

As far as I know the system does direct DPT officials to the cars with expired meters.

Here is a service that helps get cars off the street and into (reserved) parking spots that would normally be unused: http://SpotShare.com/

This is really popular in big cities.

As NYC rids itself of parking meters, it is also designing new signage that actually helps drivers understand the regulations: http://scn.sap.com/blogs/eyeball/2013/01/18/but-officer

Good article, but lacking in analysis and depth.

Randy is correct, innumerable town centres across North America have had to put in free street parking to win over the crowd that goes to strip malls and shopping malls. Downtown centres in America are dying because of sprawl, and parking meters are another nail in the coffin of mid-size urban centres.

Also, to not mention the real pioneer in North America with regards to reducing parking spots (Vancouver, BC) is just careless. Something tells me that the author became familiar with the history, but really has no idea what is being done today.

I love parking meters. They’re such tremendously convenient bicycle-locking posts. I’d like to see them on every street.

“COOL HAND LUKE” The movie! , That’s all I think about when I see a parking meter!

The biggest problem parkers are those who park for extended periods of time, because it’s “free”. Every city has some areas where there are no parking restrictions, and these tend to fill up with all sorts of long term stay vehicles. Some businesses, such as repair shops and auto body shops use the streets around their locations as an extension of their car storage areas…. It’s a pain in the butt at times.

I have a vintage Duncan Vintage Duplex/Double Head Parking Meter that has a case with a round bottom. Anyone know it’s value?

Where can I get more information?

Thanks.