Deep beneath San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza, in a windowless bunker called Brooks Hall, a 40-ton pipe organ gathers dust. Known variously as the Exposition Organ and Opus 500, the century-old instrument was a mechanical and musical wonder when it was unveiled in 1915, the seventh-largest organ in the world.

“The city of San Francisco, this pretentious fishing village, has never respected its own heritage or history.”

Back then, thousands of people a day attending the Panama-Pacific International Exposition applauded its soaring crescendos and rib-rattling swells. Today, the organ’s 7,500 pipes and countless other parts sit silent and in pieces, packed into boxes and crates spread across 3,600 square feet of concrete, basement floor—in some places, the crates are stacked 12 feet high. To prepare a new site for the instrument, move it, put the thing back together again, and then tune it could cost upwards of $2 million, assuming, of course, you could find a home for the finished instrument. So far, no one has.

That may be about to change. Although details are still under wraps, members of a group known as the Friends of the Exposition Organ have told us that after years of looking, they may have finally found a new home for Opus 500.

“In the past,” says Vic Ferrer, a documentary filmmaker and one of the Friends, “we have had discussions with potential takers from as far away as Korea. But this is San Francisco’s municipal organ. It’s the people’s instrument. It has been part of our city for almost 100 years. It belongs here because it’s a part of our cultural heritage, as important to San Francisco as the cable cars and the Golden Gate Bridge. Fortunately, we have found an owner of a local venue who loves the idea of this one-of-a-kind instrument being heard again in a new, permanent home. Now,” adds Ferrer, “we just have to raise the funds to make it happen.”

Above: In 1915, the great Edwin H. Lemare (seen at right) played the Exposition Organ to packed houses in Festival Hall. Top: Lemare beneath the organ’s display pipes, the longest of which is 32 feet.

Built expressly for the Panama-Pacific, which ran from February to December of 1915, the organ was first housed in Festival Hall, a domed, 3,782-seat, Beaux Arts pile of plaster and burlap that filled and emptied twice a day with enthusiastic crowds eager to hear the great English organ virtuoso, Edwin H. Lemare, work his magic behind the organ’s state-of-the-art console. At the close of the Exposition, when most of the temporary structures built for the world’s fair were destroyed, the instrument was moved to the city’s new Exposition Auditorium, which was built across town near City Hall and paid for with surplus funds from the Exposition. Shortly after its construction, the building was renamed Civic Auditorium and is now known as Bill Graham Civic Auditorium.

Like Festival Hall, the city’s new Civic Auditorium was designed for Opus 500, which remains the largest, most important non-structural artifact from the Exposition. The first performance in its new home was held on Easter Sunday, 1917, with Lemare again manning the keys, pedals, and stops. The last sound the organ made occurred sometime before October 17, 1989, when the Loma Prieta earthquake sent a wall of plaster crashing down on its pipes, baffles, and air box, all of which, by a cruel trick of fate, had only recently been restored.

Loma Prieta set neighborhoods on fire, flattened an elevated freeway, and shook a hole in the Bay Bridge, which is why repairing the damage to the Exposition Organ was not exactly at the top of anyone’s to-do list. In fact, it took almost five years for city officials to decide the fate of the wounded behemoth slumbering in the crippled auditorium. Finally, in mid-1994, FEMA funds in hand, all but the organ’s largest pipes and its pair of 20-horsepower blowers (each about the size of a VW Beetle) were trucked to the Austin Organ Company’s Connecticut headquarters, where the instrument had been built almost 100 years before.

Lemare gave 121 concerts at the Panama Pacific International Exposition, bringing in $5,000 more than his $10,000 fee for the event’s organizers. Photo: The Seligman Family Foundation.

Repairs were well under way when, in January of 1995, completely out of the blue, the city of San Francisco’s contractor halted work on the organ, claiming the $1,293,747 in federal monies earmarked expressly for the organ’s repair were now required for asbestos abatement back at the Civic Auditorium, which, by the way, was being remodeled as if the organ would never be returned to its rightful home. Organ supporters cried foul, and a good deal of finger pointing ensued until a compromise was struck to finish the work already in progress back at Austin, but nothing more. After Austin finished its interrupted work, the organ’s pieces were trucked back to San Francisco and unloaded into Brooks Hall, where Opus 500 has languished for almost two decades. In the end, the contractor was able to divert $450,000 in FEMA funds designated specifically for the organ’s repair to other purposes. In retrospect, this diversion of FEMA funds may have been illegal, but it’s way too late to do anything about that now.

Today, about 85 percent of the organ is ready for assembly. Many of its smaller pipes, some as delicate as penny whistles, are still packed in the boxes the Austin Organ Company shipped back to San Francisco in 1995. The larger façade pipes that never made the trip to Connecticut rest on specially designed cradles, while the organ’s longest pipe (32 feet) lays directly on Brooks Hall’s unforgiving concrete floor, the weight of the rolled-zinc pipe’s 600 pounds deforming its tube shape into a bloated oval, resembling a giant, dusty tapeworm rather than an instrument meant to deliver heavenly sounds to the ears of God.

Despite its hard-to-hide size and well-documented history, most San Franciscans have no idea this gargantuan beast sleeps in their midst. Indeed, some of its keenest supporters spent most of their lives in San Francisco clueless to the instrument’s presence. One such supporter is Michael Evje, a classically trained pianist, who along with Vic Ferrer and a former church organist named Justin Kielty comprise the Friends of the Exposition Organ.

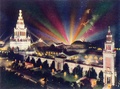

A postcard of Festival Hall, which was demolished after the Exposition.

“I was having dinner with Justin a number of years ago,” says Evje, “and he mentioned Opus 500. I said, ‘What’s Opus 500?’ and he told me the story. I’m a San Francisco native, but I didn’t go into Civic Auditorium very much, so I was totally unaware that there was an instrument in there, let alone the rest of its history. And I thought, ‘Why in the world is this thing not up and playing?’ That’s when I decided to do what I could to help.”

Filmmaker Vic Ferrer got involved with the Exposition Organ in 1997, when a group of organ enthusiasts were trying to drum up support for a plan to relocate the instrument from its purgatory in Brooks Hall to a new home they were calling the Embarcadero Music Concourse and Organ Pavilion, which was slated to be built near the Ferry Building on the San Francisco waterfront.

“The idea,” says Ferrer, “was to put it in an outside pavilion, much like the Spreckels Organ in San Diego’s Balboa Park. The group was starting to raise funds, and they had an architect who was designing a structure. I decided to document the organ’s story, from its beginning in 1915 to its anticipated grand rebirth on the Embarcadero. Unfortunately, voters nixed the Embarcadero project, of which the organ was only one part, in 2004, and so it never came to be. My story more or less died.”

During the organ’s years in Brooks Hall, successive waves of supporters came and went, from a group associated with the American Guild of Organists to those who had been working for its relocation to the Embarcadero. Often these supporters didn’t agree on what would be best for Opus 500, and in the end, says Ferrer, “everybody kind of gave up on the instrument, and I found myself holding the flame. That’s when I decided to recruit other people who were also interested in rescuing this instrument and bringing it back to life. And so Justin Kielty and I formed the Friends of the Exposition Organ. Justin brought in Michael, and for the last six or seven years now, the three of us have been pushing this project forward.”

At the close of the Panama Pacific International Exposition, the organ was moved to San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium, which was built to accommodate its 46-by-20-foot dimensions.

Of the three Friends, Justin Kielty, who was a church organist for some 60 years, has the longest relationship with the instrument, going back to the mid-1950s, when he was in high school. “There was a convocation down at Civic Auditorium for the archdiocese of San Francisco,” Kielty remembers. “They used to rent the Civic Auditorium for graduation ceremonies and things like that.”

On one of those occasions, the acclaimed organist Brother Columban Derby was scheduled to play the Exposition Organ. During rehearsal, Kielty and a friend snuck up to the instrument’s console to copy down as many of its 100-plus stops (the knobs pulled to open specific “ranks” of pipes) as he could before anyone noticed. “I had a little brown binder that had the specifications of almost every organ in the city,” Kielty recalls of his youthful hobby. “One that I did not have was Civic.”

Unfortunately for Kielty, the legendary organ master Louis Schoenstein caught the youngster in this benign act. “He was not very happy,” recalls Kielty, in his best deadpan. “He asked me what I was doing, and when I told him I was copying down the specifications, he told me to get the hell out of there.”

Lemare (in the circle at left) performing to a packed house in Civic Auditorium.

As a young man, Schoenstein had helped his family’s business, Felix F. Schoenstein & Sons, install Opus 500 at both the Panama-Pacific International Exposition and the Civic Auditorium. Given his long history with the instrument, Schoenstein personally oversaw the care and maintenance of the organ for the city of San Francisco, including keeping its secrets from the prying eyes of smart-aleck high-school kids.

As Kielty remembers it, though, Schoenstein also had a forgiving side, which he revealed later that same day by giving the inquisitive teenager a behind-the-scenes tour of the organ’s air box while the blowers were on.

“It was a fascinating experience,” Kielty remembers, as if it was yesterday. “You’d walk up to a little door, and I mean a little door, and there was a flap in the center, sort of like at a speakeasy where you’d ring a doorbell and someone would peek out to decide whether to let you in or not. When you pushed this hole in the door, the air pressure inside the box would exhaust the air lock, otherwise you couldn’t open it. Then you’d go into a little vestibule with another door beyond that, where you’d do the same thing. Your ears would pop as the little vestibule filled back up with air. Then and only then could you open the door to the main chamber. They used to say you could seat 75 people in there for dinner. As a matter of fact, the Schoensteins, who sometimes had to be on duty all day and night when conventions and things like that were going on, actually used to eat their lunch and dinner in there.”

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake sent a wall of the Civic Auditorium crashing down on its pipes, baffles, and air box, all of which, by a cruel trick of fate, had only recently been restored. Photo: Charles Swisher.

Today, that chamber is in pieces, waiting to be reassembled and filled with the air that, at the organist’s command, is forced through more than 100 ranks, or groups, of the instrument’s 7,500 pipes.

Despite all these pieces, the Exposition organ is a relatively simple machine. There’s the console with its keys, pedals, and stops, a pair of blowers, the air box, and a whole lot of pipes. The organist sits at the console, which in the case of Opus 500 has four manuals or keyboards (each similar to a piano’s keyboard, but with 61 keys instead of 88) and a pedalboard, whose 32 notes are played with the feet. There are also more than 100 stops, which open up groups of pipes of various pitch when pulled (the manuals dictate the actual notes). While the pedal keyboard generally plays the lower base notes and the manual keyboards the higher registers, together the organ’s pitch-range exceeds that of any other instrument, or even most collections of instruments.

“Any type of organ in storage is in peril,” says Hochhalter. “There are just too many things that can go wrong.”

Regardless of their size, all pipes stand on top of the air box, which is pressurized by two 20-horsepower blowers. When the organist depresses a key or foot pedal, valves called pallets open at the base of the pipes associated with that note, letting the air in the chamber rush through any of the pipes that have previously been made accessible to airflow when the organist pulled open a stop. The console for Opus 500 is designed to send its signals to the pallets electronically, which is why there are more than 100 miles of wire running through the instrument.

The greatest organist ever to sit behind Opus 500’s console was Edwin Lemare, who performed 121 concerts on the organ when it was housed in Festival Hall in 1915. He was paid a then-staggering $10,000 to play the instrument, whose keys and stops were faced with ivory.

Lemare’s tenure began inauspiciously. In fact, according to historian Nelson Barden, it almost didn’t begin at all. In February of 1915, when the Exposition opened, Europe was at war, and the waters around England where Lemare lived had been declared an exclusion zone by Germany. Complicating matters, Lemare’s third wife, Charlotte, was expecting her second child. But Lemare was determined to get to San Francisco, lest his lucrative contract for 100 performances, which were supposed to begin in June, was cancelled. Thus, the family booked passage on the Lusitania, due to leave Liverpool on May 11 after it had steamed across the Atlantic from New York.

All 40 tons of the Exposition Organ, including its zinc pipes, are currently in storage in Brooks Hall, which is hidden beneath Civic Center Plaza.

As any school kid who has studied World War I history knows, the ship never made it to England, sunk by a German torpedo, killing almost 1,200 passengers and crew. Crossing the Atlantic was now deemed a hazardous trip, but somehow, despite the tragedy of the Lusitania and the hostilities raging around him, Lemare managed to get a ship on August 4. A month later, his family, including his newborn daughter, secured berths on the last passenger steamship to leave Liverpool until the war’s end in 1918.

Against this emotional backdrop, it must have been a serious disappointment to Lemare when only 400 people showed up for his first recital on August 25, 1915. But that would be one of his few concerts not to sell out at 10 cents a ticket, a premium over and above the 50-cent admission to the Exposition itself. By the end of the Exposition, more than 150,000 people had paid their dimes to hear Lemare, which means he raised $5,000 more than his salary for Expo organizers.

Despite its magnificence, the organ was never the draw. Rather, it was what Lemare did with it. His repertoire typically included everything from Bach fugues to his own famous composition, “Andantino in D-flat,” which, in 1921, became a popular song of the day, “Moonlight and Roses” when Ben Black and Charles N. Daniels added lyrics to the melody (Lemare had to sue to collect his share of the royalties). Lemare also took requests, though not for songs or specific pieces of music. Instead, musically literate audience members would write three-bar themes on slips of paper, and then Lemare would choose the ones he liked best and improvise on them. For encores at Festival Hall, Lemare gave the crowds gathered for the world’s fair a deliberately patriotic rouser, “The Stars and Stripes Forever.”

Michael Evje standing at the tapered feet of the organ’s display pipes. Air from two 20 horsepower blowers enters all of the organ’s 7,500 pipes through these smaller ends.

After the Exposition closed, Lemare was hired as the city of San Francisco’s first, and last, Municipal Organist, for which he was paid his by-now familiar rate of $10,000 per year. At a time when the average annual U.S. salary was only $1,000, and the head of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, J. Emmet Hayden, was making $1,500, this rubbed many the wrong way. Indeed, Hayden led the campaign to lower Lemare’s salary. In a bid to appear magnanimous, Lemare volunteered a reduction of own, though not as much as his critics were demanding. By November of 1920, Lemare’s salary had become such a political hot potato that voters approved an ordinance reducing his salary to just $3,600. While still handsome, this new rate struck Lemare as a personal rebuke, so he quitted San Francisco and went off to become the municipal organist of Portland, Maine, and then Chattanooga, Tennessee, each of which had its own Austin organ, which were built in Hartford, Connecticut, by the same Austin staffers who designed and assembled Opus 500. (A two-year, $2.6-million restoration and reinstallation effort in Portland is on budget and on schedule.)

Lemare returned to San Francisco in 1925 to play a sold-out engagement at the Civic Auditorium, but by then, organ recitals had largely fallen out of favor. The sonorous sounds produced by pipe organs seemed tired and treacly compared to the fun, fast-paced rhythms and toe-tapping beats of 1920s jazz, which was widely promoted in clubs and on a recent invention, the radio. In the decades that followed, the Exposition Organ in the city’s Civic Auditorium would be played less and less, a quaint albatross from a bygone era. In some respects, the instrument was already in storage, except that its parts were fully assembled and it was housed in a room designed to bring out its best. But in 1962, even that benefit was eliminated when an ill-conceived remodel of the hall sucked the life out of the organ’s acoustics. Those who heard it before 1962 and afterwards swear the instrument never sounded the same.

Also in storage in the organ’s console, which replaced the original in 1963. It features four manuals or keyboards.

Edward Millington Stout III, considered the dean of the San Francisco organ scene, is one of those people who heard Opus 500 before and after the remodel. Stout knows how to get the most out of everything from modest movie-theater Wurlitzers to classical organs like the one at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral, where he served for 42 years as the institution’s organ curator. For Stout, the reason for Opus 500’s auditory decline after the Civic’s disastrous facelift in 1962 is hardly mysterious.

“Over the centuries,” Stout says, “cathedral designers figured out that the best position for an organ was in the back gallery, halfway up the wall. The position of the pipe chamber, the wind chest, and so forth is crucial. And then, how jubilant the organ sounds depends on the room it’s speaking into, in terms of both its cubic volume and reflective surfaces. So, when they lowered the ceiling in the Civic Auditorium above where the organ sat, it lost a lot of its luster and impact. They basically ruined a fine room by radically changing its acoustics. But the city of San Francisco,” Stout adds, “this pretentious fishing village, has never respected its own heritage or history. The cable cars would all be gone if some ladies hadn’t made a big squawk. It’s an old story.”

When the stops on Opus 500 are opened by pulling them out, air is allowed to flow through ranks, or groups, of pipes, which give the notes played by the organist different tones.

For supporters of the Exposition Organ, saving this irreplaceable piece of the city’s heritage is an opportunity to right a wrong, as well as to avoid painful mistakes that lost the city landmarks such as the incomparable Fox Theatre, which was unceremoniously leveled in 1963 to make way for the joyless, 29-story nightmare of an office building that replaced it (silver lining: the Fox’s 4,000-pipe Wurlitzer was saved, and is now housed in Hollywood’s El Capitan Theatre).

“Hearing a pipe organ in an acoustically beautiful space, where the bass notes rumble your body and the high notes bloom, will change you,” says Vic Ferrer. “Pipe organs have this bad rap as being about weddings and funerals. They’ve become a joke, like the church lady on ‘Saturday Night Live.’ But that is so far from what a pipe organ really is. These are works of art worthy of preservation.”

After Louis Schoenstein retired and before Loma Prieta damaged the Exposition Organ in 1989, Jack Bethards was in charge of this work of art. “When I bought Schoenstein & Co. from the Schoenstein family in 1977,” he says, “I ended up being the main custodian of the organ, doing most of the tuning and so on. It was a wonderful experience to work on that beautiful instrument.”

The organ’s largest façade pipe is 32 feet long. Its storage on the floor of Brooks Hall has done more damage to it than the earthquake. In the background are many of the organ’s wooden pipes.

Bethards admires Opus 500 for multiple reasons. “First of all, it is a solid, well-designed, beautifully voiced musical instrument. It’s not just a big curiosity. In addition, the Austin organ is a fantastically brilliant bit of technology and invention. It’s efficient to maintain, efficient to build, efficient to install. It’s really a wonder of the industrial age, a marvel of engineering. There’s no concert organ of its type anywhere in California, or even in the West,” he adds.

All of those sterling qualities are expensive, but back in the day, organs like Opus 500 were populist instruments, allowing listeners to enjoy a symphonic concert experience for only a dime. “You have to remember,” says Ferrer, “that not everybody got to go to the symphony back at the turn of the 20th century. A symphonic organ like Opus 500 is capable of producing all the different timbres to mimic what a symphony actually sounds like, allowing the organist to replicate what the composer meant his audiences to hear. The organ was a way for the masses to access Wagner.”

In fact, a quick scan of the organ’s stops, which are the knobs the organist pulls out to open ranks of pipes, reveals the orchestral roots of the instrument. On Opus 500, there are stops labeled Flute and Piccolo, others designating all sorts of flavors of Tuba, Trumpet, and Trombone. The Vox Humana stop produces choirs and choruses, while pulling out Voix Celeste summons strings.

One pipe sports a bullet hole from its years in Civic Auditorium, but no one knows who pulled the trigger or why.

That’s just a sample of what the organ can do, but it’s nothing more than an enormous noisemaker without the right room. “The pipe organ itself is only half of the instrument,” says Ferrer. “The other half is the room the instrument speaks into. The room becomes the sounding board, almost like a piano’s sounding board or the back of a cello. The room influences the sound.”

When the ceiling in the Civic Auditorium was lowered, the acoustic influence was largely negative, which may have been one of the unsaid justifications for kicking Opus 500 to the curb when it was sent back east for repair in 1994. After all, if the thing didn’t even sound like it was supposed to anymore, why bother to reinstall it? But that level of logic assumes that the powers that be actually cared about the Exposition Organ at all. More likely, someone just wanted the floor and wall space, unencumbered by an enormous pipe organ.

“It took up a huge amount of space,” says Lanny Hochhalter, a respected pipe organ tuner and technician, who happened to be working at Austin when more than 30 tons of Opus 500 were scattered about the company’s Connecticut headquarters for repair. “Its footprint was 46 feet wide by 20 feet deep, and it was set on a nice platform above the stage. That real estate probably looked pretty attractive to somebody, or at least that’s my theory.”

The hardware inside the pipes is as good today as it was almost 20 years ago when they were restored by the Austin Organ Company of Connecticut, which built the organ in 1915.

Hochhalter also blames changes in musical tastes for the instrument’s eviction, as classical music forms were steadily pushed aside by pop. “When Lemare played recitals on it, they filled up the Civic Auditorium,” he says. “But when he moved on, the novelty petered out. Churches would rent the Civic Auditorium for conventions, and the organ would get played on special occasions, like when the symphony wanted to use it for a particular piece. But the Civic Auditorium is such a vast building. You couldn’t have a normal organ recital in there.”

“Hearing a pipe organ in an acoustically beautiful space, where the bass notes rumble your body and the high notes bloom, will change you.”

“If you wanted to hold a concert in the Civic Auditorium,” agrees Justin Kielty, “you’d have to sell a hell of a lot of tickets. Just to have someone from the union turn on the electric blowers was a $500 deal. To use the Civic Auditorium for even a small concert, you were probably looking at five grand in expenses, at least.”

Despite these negatives, from the lowered ceiling that compromised the organ’s sound to the crazy expense of even turning the thing on, having the instrument exiled to Brooks Hall added injury to insult. “Ed Stout once told me that the worst thing you can do to a pipe organ is to remove it from its building,” remembers Vic Ferrer, “because once you remove it, there will always be nefarious forces out there who will want to keep it from coming back in. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened at the Civic Auditorium.”

Now that a new home for Opus 500 is on the horizon, the Friends are thinking about ways to make sure the organ will never be uprooted again. “We see the reinstallation of the Exposition Organ as an educational opportunity,” says Kielty, recalling the privileged tour he got of the instrument at an impressionable age. “We’re modeling our plans after several other successful pipe-organ installations around the country, in which the instrument is playable but can also function as an exhibit, with windows and access to allow students of all ages to get a behind-the-scenes view of how a pipe organ works. Understanding the basics of wind pressure, pipe design, and the organ’s control mechanisms affords the viewer an extraordinary demonstration of physics, mathematics, metallurgy, and, of course, music.”

One of the organ’s smallest pipes.

Doing everything they can to make sure the Exposition Organ will be secure in its potential new home is critical because the Friends know the clock is ticking. On the most basic level, there’s a strong sense the instrument has worn out its welcome in Brooks Hall, and that the city would like to use the not-insignificant amount of floor space it consumes for other purposes.

“The city has other storage areas where they actually have to pay rent,” says Evje. “What they’d like to do is eventually clear the organ out of Brooks Hall to reduce their outside-storage costs for other things. Plus, there’s a whole generation of people in City Hall who don’t even know of its existence,” says Evje. “It’s out of sight, out of mind.”

Supporters are also concerned about the storage itself. “The things we worry most about are flooding, fire, and vandalism,” says Kielty. “We came close a couple of times on vandalism.”

“Any type of organ in storage is in peril,” agrees Hochhalter. “There are just too many things that can go wrong. For example, the organ’s underground, so if a water main breaks above it, that could easily destroy the organ. We’ve had rats and mice in there, and a few feral cats. All of that can cause damage. And those big, long pipes are meant to stand up. They’re not designed to lay on their sides.”

A number of wooden pipes, from the large gray one on the floor to smaller examples. Most are made of sugar pine.

Time is also not their ally when it comes to the loss of continuity at Austin. “Imagine dismantling a pocket watch and putting it in a drawer for 20 years,” asks Hochhalter, “and then trying to reassemble it. I’ve talked to the guys at Austin, and they’re starting to forget what was done.” Sure, there was documentation, he says, but the erosion of the institutional memory at Austin will only make the remaining repairs that much more difficult, and costly.

And then there’s 2015, the 100-year anniversary of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, perhaps the most important deadline of all. When it comes to bringing history to life for people, a centenary can be a powerful catalyst, prompting press attention and the interest of donors. For the Friends of the Exposition Organ, 2015, now less than a year away, is perhaps their most persuasive call to action to would-be supporters.

“We are on a very, very tight timeline,” says Kielty. “It’s not just a matter of moving this beast into its new home, but getting it up and running again. If pieces have to go back to Connecticut, that will take time. We know the façade pipes are going to need work, and somebody may have to build a few new tuba pipes. All of this is going to take time. You don’t just say, ‘Do it’ and then everything is fixed in a week. It doesn’t work that way. So we’re under the gun, and if we’re going to get it done in time for the celebrations being planned for the Exposition’s centenary, we’re going to have to get moving, like now.”

(Special thanks to the following people and organizations for their help with this article, including research sources and photographs: Jack Bethards; Lanny Hochhalter; Austin Organs, Inc.; Charles Swisher; Nelson Barden; Edward Millington Stout III; and The Seligman Family Foundation. For more information about the Exposition Organ, visit Friends of the Exposition Organ.)

The iPod's 4,000-Pound Grandfather

The iPod's 4,000-Pound Grandfather

From Rubble to Riches: The World's Fair That Raised San Francisco From the Ashes

From Rubble to Riches: The World's Fair That Raised San Francisco From the Ashes The iPod's 4,000-Pound Grandfather

The iPod's 4,000-Pound Grandfather How a Gang of Harmonica Geeks Saved the Soul of the Blues Harp

How a Gang of Harmonica Geeks Saved the Soul of the Blues Harp Worlds Fair MemorabiliaThe first world’s fair recognized by the Bureau of International Exposition…

Worlds Fair MemorabiliaThe first world’s fair recognized by the Bureau of International Exposition… OrgansSince the middle of the 20th century, the words “organ” and “Hammond” have …

OrgansSince the middle of the 20th century, the words “organ” and “Hammond” have … Musical InstrumentsWhether it's a clarinet or an accordion, a piano or a trombone, musical ins…

Musical InstrumentsWhether it's a clarinet or an accordion, a piano or a trombone, musical ins… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Seriously? I can’t believe anyone would really consider this a serious priority. I’m sure this pipe organ is a wonderful artifact, but it’s just that – an artifact from a past time, whose relevance is totally gone now. Guess what, nobody cares about this in San Francisco except organ lovers. There are many, many more important things to spend money on, and the city is right to push this to the side.

As a native San Franciscan now in exile, and a musician who remembers hearing Opus 500 in the Civic Auditorium, I am thrilled to hear that a group is working toward bringing this historic instrument back to life. This organ should be honored and treasured as much as its contemporary, the Palace of Fine Arts. Sometimes the City has been cavalier about destroying its past (I’m thinking in particular of the Fox Theater), but I hope that in this case, as with the cable cars, important history will be preserved to delight future generations.

@ John “I’m sure this pipe organ is a wonderful artifact, but it’s just that – an artifact from a past time, whose relevance is totally gone now.”

Artifacts from the past are what retain our collective memory and appreciation of those who came before us and remind us of their contributions to our society, culture and history. Just ask any one of the thousands of folks on this site who post ‘Show and Tells’ of their “artifacts.” They will tell you that their treasures *DO HAVE RELEVANCE*. “Artifacts” teach, inspire and remind us of who we were while propelling us forward into the future. This pipe organ is a supreme example.

What a cold and heartless world we would have without our history and artifacts. Practicality has its place of course, but not at the expense of our heritage. And what some might consider “junk” today may be treasured tomorrow. Yes, to this day San Franciscan’s regret loss of the Fox, all over a small amount of money that was needed to save it. Denver also regretted loss of the Tabor Grand Opera House, torn down I believe in 1958. It wasn’t five years later when everyone understood the loss to Colorado’s heritage.

There was a plan to place this fine instrument in a Pavilion on the Embarcadero in the style of the San Diego Balboa Park Austin. Is that dead?

Although modern technology such as I am using right now, is vastly improved over that of ten years ago let alone a 100 years ago, craftmanship is not only increasingly rare, but unfortunately in many fields, a dying or extinct art. Many modern examples which cannot match timeless flair, panache and quality of their predecessors. As is the case with the Opus 500. It is a slam dunk money used for its restoration will yield a priceless rate of return on this investment.

To answer Mark Fownes: the Pavilion on the Embarcadero was part of a larger bond measure which voters turned down. Some of us believe that weather conditions as well as noise factors would have made the Embarcadero project a failure were it to have been built. The San Diego Balboa Park Austin enjoys beautiful weather in quiet surroundings.

@ John:

This organ actually has considerable relevance. Many of the nation’s premier music and performances venues are seeking/acquiring pipe organs, like Disney Hall in LA, The Kimmel center in philadelphia, and the Atlanta symphony center (if it will ever be executed). It is the opinion of many that a first class music venue is not complete without a fine pipe organ. These are prized and cherished objects, and these current trends certainly belie any irrelevance.

This subject brings up so many feelings. A comments sections is so inadequate! Housing an instrument like this in a warehouse is one discussion question. What else to do with it is another. One other large organ I know of was burned while waiting in warehouse storage. When is the right to move on it and how do you proceed? With all of these questions and many more, we could fill a three-day convocation! Bravo on the video, Vic!

I am quite surprised at John’s notion of this organ as an irrelevant artifact. What are these “many, many more important things to spend the money on?” The past helps us remember who we are as humans and allows a perspective and enjoyment of art in many forms, which engenders further creativity for most everyone. Most certainly this instrument was and can be a thrill for anyone in the city and beyond. I have seen the loss of Frank Lloyd Wright buildings and of many other historical elements in our nation. This only diminishes our perspective of who we are as people and as well as a nation. The Fox Theater was a prime example of this type of thinking. I lived in San Francisco for a short two years, but took in the wonders of the city and all it had to offer culturally in every way. Yes, I am a musician who happens to play the organ. John is obviously poorly acquainted with the instrument and would likely change his mind were he to take the time to listen to what the city has to offer in its’ other venues with pipe organs. This instrument sounding again would only further enhance the cultural wonders of San Francisco.

I’d love to see this instrument get restored. I know the person who has the original console, and know someone else who has helped restore the original console.

America, not just San Francisco, is a place that throws away its past, often to regret it later. Americans then visit Europe for the richness of its history and culture, including its architecture, historical buildings, cathedrals, even pipe organs–all the things that comprise a deep cultural heritage, the things that define a people and give that people true lasting significance, so much more than the mere thinnest film of the latest technological development and social trend. I too am a musician, a fan of the pipe organ, but I applaud “us,” Americans, every time we save ~anything~ of merit from our past, and I support our doing so. I derive tremendous enjoyment from seeing old churches, fine old buildings, Colonial houses, old machinery, steam locomotives, outdated technology that once powered our country, even dilapidated farm buildings; not to mention art and craft from bygone eras. I had the pleasure to spend a night in a house built in 1870. It was an experience to simply be there in the presence of 140 years’ history. In my part of the country, we have nothing of that age, and very little the age of this significant pipe organ in San Francisco. I hope those who do have such heritage in their neighborhoods don’t take it for granted, and I hope they aren’t prejudicial about “which bits” of heritage they choose to preserve. Certainly America has the resources to do better than simply say, “It’s not a big priority. Haul it off for scrap.” Populist America–not the world, but America–is in a “hate the organ” phase at present. In spite of this, there are significant new instruments being commissioned, as other posters have mentioned. The instrument survives despite the current popular climate. Everything ages: first popular, then worn, then out of fashion, then rejected. Then another generation comes along with fresh interest, sometimes excitement; restorations take place. If we destroy during the rejection phase, we deprive the future. Let’s hope that San Francisco, or even a few people with the means, will step up to the plate and rescue this substantial old Austin, both for its historical and musical value. Atlantic City is at last doing it with the Boardwalk Hall organ, a far more vast and expensive project because of its overwhelming size. San Francisco, it’s your turn.

I live in a major capitol city in another part of the world where we have a very large concert pipe organ (150 ranks, seven of those at 32′ pitch) in our town hall which, like Opus 500 was originally built on a grand scale and to have the resources to play a wide variety of music. Having originally been built in 1929 it served the city well for decades and naturally with time, things needed attending to. That work was done at a cost of close to $5 million and that instrument is one of our major assets. You could not build an instrument on such a grand scale now, costs alone would prohibit that. Concerts are held on it regularly and even non-organ minded people have told me how much they love it’s sound. It is an instrument which has been and always will be an important part of our city’s heritage and culture. I hope that a suitable venue is found for Opus 500 so that not only the people of San Francisco can again hear this wonderful instrument but that it can be shared with the world. Yes, I’m an organist and value these instruments as I know something of what can be done musically with them. All credit to those who are involved with the project.

You’re so correct John (comment Jan 20). There are so many more relevant endeavors to consider, like bank bailouts where a lot of the money went to the CEO’s and top tier bonuses and severance packages; nation building and WAR. What is more important than rebuilding two ungrateful nations on the opposite side of the planet, which, in 10 years time, will yet again stab us in the back, requiring us to invade once again…assuming this time we ever leave that region. You’re right. What good or relevant use is heritage and culture? When the majority of our youth are too stupid to understand the meaning of the term as they step off the curb into traffic with their nose and thumbs buried in their Smartphones.

What relevance does it have? I tell you what. It’s for US, the people that have worked their butts off to make the world better. For US, those that do know the meaning of culture and heritage.

Please elaborate what is more important? Welfare for illegal immigrants? The embarrassment called the Folsom Street Fair (I’m same-gender-attracted so I have the right to criticize).

Pray tell, John…you opened the door. What IS more important than our history, heritage and cultural excellence? Nothing. Without it and an understanding and appreciation, we’re just another species of untamed beast…

Ya know what? I’m kinda poor; but not so poor (or obscenely wealthy) that I get to avoid paying taxes.

But a few million dollars to restore this historic treasure is a mere pittance in the budget of a city the size of SF.

Yeah, that’s right. A few million is a drop in the bucket.

It’s laughable in the grand scheme of infrastructure, services, etc that the city is responsible for providing.

Where I live, there isn’t a single similar project that has come to be regretted. The only regret was the blindered, ignorant choices of the short-sighted, that left us with nothing more than hollows and dusty memories of what was once unique to us.

Hoping that some philanthropic group/individuals can come through before the misanthropics have their misguided say.

Pipe organs are dinosaurs. Ancient relics that once afforded the listeners an auditory delight. That was many, many, moons ago. Who actually cares about, or is interested in pipe organs anymore? It’s likely an esoteric fringe of organ lovers many of whom are of an advanced age that can “identify” with these egregious instruments. I’m positively baffled as to why anyone would want to spend hundreds of thousands, even millions of dollars to restore a pipe organ! It makes no sense especially when it’s state or city funds being wasted on rebuilding a pipe organ. There are fewer and fewer people who care about organs anymore, so the most relevant thing to do with pipe organs is to disassemble them and recycle all of the metal and wood. Surely something useful can be produced from all of those recycled organ components.

The “Mechanics Hall Organ” you show is the 1864 E. and G.G. Hook Mechanics Hall Organ in Mechanics Hall in Worcester, MA. In 1982 full reconstruction was finished by Noack as Op. 92 and added to and retuned in 2003-2004 and who now maintains it. Hook built many organs in New England but Worcester’s is the largest with four manuals. See it at organweb.com/specs/mech-hall.html. Mechanics Hall is a beautifully restored “world class” venue with stunning acoustics. I know of only one other organ of its equal and that is the Boston Symphony Hall Organ at Methuen Memorial Hall in Andover, MA. Worcester did not give up on its “organ dream”, neither did Atlantic City and neither will San Francisco. 42 tonnes of love.

I can’t believe some of the negative comments here. We need to do everything to save this SF treasure but one question. Has a new home really been secured and if so, where? Thank you. Hi Irving: As of 1/1/15, no home has been secured, alas… Thanks, Ben

John and Michael,

What are your favorite kinds of music, who are your favorite artists, and what are some of your favorite songs and/or instrumental pieces? I am curious.

This does have relevance to the topic at hand, which is this pipe organ, or at least the pipe organ in general.

However, until I receive a response (it doesn’t have to be EVERYBODY you like, if you don’t want to list all of your favorites, just a couple of artists/musicians), I can’t give a more detailed reply.

Thanks a lot for your time,

Andrew Barrett

San Francisco is known Internationally for many things, at the top being the Panama Exposition of 1915. The Austin Pipe Organ was heard by thousands of people until the late 1980’s, and now sits in a basement awaiting restoration. I have heard many Pipe Organs around the Country, and wherever one remains, it is beloved by its’ Citizenry. Where could such an appreciation possibly exist other than in the City of San Francisco?

The City lost its’ grand Fox Theater with its’ Mighty Wurlitzer Pipe Organ unfortunately, and now has a chance of redeeming itself by placing this Pipe Organ back where it was originally located in the Civic Auditorium. Money was allocated for the restoration, re-installment by FEMA at the time of the Earthquake, and that money mysteriously changed hands, along with seeming efforts by the City Officials to simply do nothing. Get Gavin Newsom, Diane Feinstein and Willie Brown on the Band Wagon to get this Pipe Organ playing again along with your current elected City Officials.

Such an approach in saving the Panama Exposition Pipe Organ does not seem to be the San Francisco known by the World. Don’t disappoint the rest of us that visit the City by the Bay, and especially don’t deny your own citizen’s the joy of hearing the unique sounds of this Historic Instrument in a building with acoustics worthy of its’ presence.

Remarkable article. I am also aware of the Pipe Organ that once played at the Oakland Fox Theatre which until a year ago was serving St. Peter’s Church also in Oakland. Certain members are currently looking for a new home for the organ.

If you’re curious about “who actually cares about, or is interested in pipe organs anymore”, go attend one of the many organ recitals around the world. Here in San Francisco several hundred people come to the Legion of Honor every weekend on Sat/Sun to hear the organ recitals. Grace Cathedral hosted several hundred last Sunday. SF Symphony Hall is almost sold out for every organ concert. Have you ever been to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London for an organ recital, or the Spreckels Organ Pavilion in San Diego, or the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel in Chicago, or Meyerson Symphony Hall in Dallas, or the Wanamaker Organ in Philadelphia, or the Boston Symphony Hall Organ at Methuen Memorial Hall in Andover, MA? They host thousands of people. The American Guild of Organists (AGO) serves approximately 15,000 members in more than 300 chapters throughout the United States. The point of the article is that we have one of the most incredible organs anywhere in world sitting in storage right here in San Francisco, and it should be resurrected and played!

A Yamaha keyboard plugged into a 1000 watt bass amp with 2×20″ subs will dwarf any pipe organ in sound.

John and Michael: someday you will more than likely come to see the relevance.

Ari Tarver: that would probably sound wonderful in the right acoustic environment. Then when you listen to a REAL organ in the proper space you will see its not the same. It’s not just loud we’re speaking of, but that the sound seems to come from every direction constantly changing. Why else are the makers of imitation organs spending big dollars trying to make them sound like the real thing.

Being a great fan of all three of San Francisco’s world’s fairs, I am dumbstruck that this so proud and arrogant city would let this magnificent treasure of an instrument rot in a basement. Having read the article I realize now how close it came to complete repair–75%!!–before the project was abandoned and the pieces shipped back to SF. Like others here I have been to organ concerts all over the place, including several treks to San Diego for concerts at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion. How I would love to see a magnificent instrument like this in use again, as beloved to San Franciscans as the Palace of Fine Arts.

I want ADD a XIII-XV Mixture stops!

Dolce Cornet III!

X Chous

I want to bring it to France