In today’s Etsy Era, in which everyone aspires to be an artisan (or at least shop like one), embroidery is an exotic handicraft, as incomprehensible to most consumers as blowing glass or brewing beer. But from the 16th century on, girls were schooled in the mysteries of needles and thread by creating samplers, which taught them simple stitches as well as their ABCs.

“People like Gustav Stickley had a vested interest in promoting embroidery.”

By the end of the 19th century, the ways of embroidery were virtually encoded in every woman’s DNA. Coincidental to embroidery’s ubiquity were improvements in printing technologies, which spawned a proliferation of women’s magazines and catalogs published by thread companies, each packed with embroidery patterns for throw pillows, table runners, and decorative panels. Through embroidery, the first modern do-it-yourself movement was born.

One of the most popular styles of this period, in the United States as well as in Europe, was Arts and Crafts, which represented a clean, modern look for those fed up with the fussiness of Victorian design or scandalized by the immodesty of Art Nouveau.

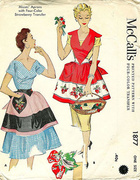

Top: An example of a particularly well-executed Little Bo-Peep embroidery, stitched from a design sold by London’s Liberty & Co. Above: Embroidery patterns were featured in thread-company catalogs such as these examples from the early 20th century.

“Embroidery was a very popular pastime among women,” says Laura Euler, whose excellent “Arts and Crafts Embroidery” was published by Schiffer earlier this year. “Most women did some kind of embroidery back then, decorating pillows or monogramming sheets, what they called fancywork. It wasn’t a niche thing.”

According to Euler, embroidery was well suited to the tenets of Arts and Crafts design, which rejected excessive ornamentation and naturalistic depictions in favor of what were called “conventional,” graphic, treatments. Thus, Euler writes, “a rose should look like a Tudor rose, or a Glasgow rose, not a three-dimensional rose with shading.”

Embroidery also lent itself well to the Arts and Crafts ideal of “truth to material.” To explain the practical meaning behind this cryptic phrase, Euler quotes from an 1878 publication called “Art Needlework,” which also used flowers to make its point: “It is as impossible to reproduce the odor of flowers as it is to imitate the bloom of their texture, the delicacy and evanescence of their more brilliant tints, or the minute details of their form. The attempt, once and for all, must be abandoned….”

William Morris’s Honeysuckle pattern from 1876 was a favorite of his daughter May, who took over the embroidery department at Morris & Co. in 1885.

Which is not to say Arts and Crafts embroidery was uninspired or halfhearted, as the designs of the father of Arts and Crafts in England, William Morris, his daughter May, and Morris designer Henry Dearle attest. Their intricate floral patterns in rainbow hues of silk floss set a high bar for the form, and generations of stitchers have struggled to replicate the ostensible simplicity and unrivaled quality of their work ever since.

Beyond the appeal of embroidery as a distinct decorative art, embroidered fabric served a useful purpose within the world of Arts and Crafts more generally, especially when it came to textiles made for Arts and Crafts furniture. “People like Gustav Stickley had a vested interest in promoting embroidery,” Euler says. “His stark furniture looked more appealing when his tables had nice, long runners on them, or when his incredibly uncomfortable sofas were accented with soft cushions.”

In fact, Stickley actively promoted Arts and Crafts embroidery in his short-lived, but highly influential, publication, “The Craftsmen,” often highlighting the work of other Arts and Crafts designers. For example, the August 1903 issue featured patterns for eight portieres (curtains designed to be hung in doorways that do not require actual wooden doors) by architects/designers Harvey Ellis and Claude Bragdon.

But the real popularization of Arts and Crafts embroidery came from more mainstream sources, including women’s magazines such as “Modern Priscilla” (1887 – 1930) and “Home Needlework,” whose first issue dropped in 1899. In these publications and others, patterns were typically bound into the magazine so that the reader could remove it and then embroider a throw pillow, napkin, or laundry bag at her leisure.

Concurrently, American floss companies such as Nonotuck, Verran, and Belding published catalogs and kits for aspiring embroiderers, often packaging a stamped piece of fabric, various colors of silk or cotton, and sometimes even a needle for the convenience of their customers. While the patterns in publications were designed to sell magazines, the catalogs and kits were designed to move thread.

Detail of a linen table runner, embroidered in silk, from Corticelli.

While the Arts and Crafts movement may have evolved from lofty ideals such as “truth to material,” the people who ran thread companies understood marketing and branding, which is why, for example, Nonotuck Silk Co. of Northampton, Massachusetts, promoted a thread brand called Corticelli, to give the easily replicated commodity a romantic, Italian sensibility. Verran sold its thread and embroidery kits under the wealthy sounding Royal Society brand, even though its cotton thread and rayon floss, Euler writes, were less expensive than the silk floss sold by its competitors. As a point of reference, a typical Richardson Silk Company pattern, without the floss, cost 15 cents; selling thread was business of a lot of nickels and dimes, so differentiating your product in a marketplace where brand loyalty was largely absent was especially important.

Royal Society patterns were often inspired by the Glasgow style of Arts and Crafts.

Cleverly, or so it seems in retrospect, Royal Society promoted the Glasgow variant of Arts and Crafts favored by Scotsman Charles Rennie Mackintosh and American Frank Lloyd Wright, a sophisticated, somewhat minimalist aesthetic that was less detailed than a traditional William Morris design. It could be the powers that be at Verran simply liked Glasgow design, or they might have thought their customers would find the patterns more accessible than busier ones, but simpler designs required less thread, which may have helped Verran keep its costs to consumers low.

“It is as impossible to reproduce the odor of flowers as it is to imitate the bloom of their texture.”

Because so much Arts and Crafts embroidery was produced from kits by home embroiderers, whose training and skill varied greatly, vintage pieces on the market today are far from uniform. “People were expected to have a certain amount of knowledge about embroidery,” says Euler, “but many of the published patterns left a lot up to the person doing the work.” Although colors and stitches were often specified, she says, sometimes even that was left up to the embroiderer, as were more subtle details such as shading.

To illustrate how much difference a needleworker’s ability could make, Euler points out a Liberty & Co. pattern for a panel featuring Little Bo-Peep standing beneath a tree, her face buried in her hands, her lost sheep grazing in the distance behind her (see top images). “That is a particularly good Bo-Peep,” Euler says admiringly. “It must have been a very popular pattern, because I see that one coming up for sale once or twice a year. Somebody with real embroidery skills did that one,” she adds. “Some of the other versions I’ve seen are not nearly as nice.”

Author Laura Euler found this untouched linen embroidery pattern in a 1902 copy of “The House: The Journal of Home Arts and Crafts.”

The quality of a vintage Arts and Crafts embroidery goes beyond an embroiderer’s aesthetic sense, color choices, and the like. Embroidery is about stitching, and in the end, it is stitching that’s on display. “There are just an enormous number of embroidery stitches out there. Satin stitch is probably the most common stitch you’ll find,” Euler says, “but as someone who’s a mediocre embroiderer herself, I can tell you that a good satin stitch is very difficult to do well. You have to be careful to get it even and straight, you don’t want it to be lumpy. Other stitches like the chain stitch or stem stitch are much easier. In American embroidery, the outline stitch was used a lot for flowers and other objects. In European embroideries, you don’t see flowers and things like that outlined in the way you do with American embroidery.”

Still, most Arts and Crafts embroiderers did not practice their craft to show off their stitching skills, let alone to produce flawless artifacts for future generations to ogle over. The whole point of the kits and patterns, as well as the mission of Arts and Crafts, more generally, says Euler, “was that everyone should enjoy handicrafts, to enjoy making things and beautifying your home. That’s something I try to remember when I do my own stitching. My embroidery may not look as good as the antique pieces I collect, but that’s not what’s most important.”

One of Euler’s favorite pieces in her book is this unfinished linen cushion cover, whose 1910’s embroiderer appears to have taken the slogan’s advice too much to heart.

Even William Morris, the father of the Arts and Crafts movement in England, had uses for embroidery that went beyond mere aesthetics or displays of stitching dexterity. “William Morris supposedly took up needlework to steady his nerves,” says Euler. “He was famous for being short-tempered and cranky, so he did embroidery to calm himself down.”

(All photos courtesy Laura Euler. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

When Housewives Were Seduced by Seaweed

When Housewives Were Seduced by Seaweed

Angry Chicken's Amy Karol on Sewing, Vintage Slips, and Her Apron Obsession

Angry Chicken's Amy Karol on Sewing, Vintage Slips, and Her Apron Obsession When Housewives Were Seduced by Seaweed

When Housewives Were Seduced by Seaweed From Little Fanny to Fluffy Ruffles: The Scrappy History of Paper Dolls

From Little Fanny to Fluffy Ruffles: The Scrappy History of Paper Dolls EmbroideryHand-stitched embroidery is one of the oldest ways to decorate rugs, clothi…

EmbroideryHand-stitched embroidery is one of the oldest ways to decorate rugs, clothi… Arts and Crafts EraThe Arts and Crafts movement that swept the United States and Great Britain…

Arts and Crafts EraThe Arts and Crafts movement that swept the United States and Great Britain… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Thank you for the very interesting article! I hope you don’t mind my translation and posting it here: http://smilylana.blogspot.hu/2013/11/dawn-of-diy-when-it-was-hip-to-stitch.html with all references, of course.

Thank you for this informative article. I live in a Craftsman bldg. and always looking for the right items for my apartment. It’s difficult to find original hand embroidered items.

Thank you for this post (I was directed here from Root Simple). Aside from my general interest in Arts & Crafts stuff, I own a Royal Society embroidery floss display cabinet (I use it to display items from my British royal commemoratives collection!) and am glad to learn more about the company’s history.

I would like to get the neddlework on this page.