Some stamp collectors are obsessed with first-day covers, while others love fancy cancels, but only a handful of philatelists harbor postal passions that could be described as explosive. You might say Dale Speirs is one such collector—the pieces of postal history that get him excited are parcel and letter bombs. Not the unexploded variety, of course. Rather, Speirs is interested in evidence of these often fatal forms of philately, such as a mark on a letter verifying it’s been “bomb inspected,” or perhaps an envelope that somehow survived incineration in a mailbox that was intentionally set ablaze.

“Today, it’s generally more difficult to send something nasty through the mail.”

“I was always attracted to the oddball stuff,” Speirs told us recently. “The world did not need any more articles on how Sir Rowland Hill invented the postage stamp.” For Speirs, mail bombs went beyond even the “oddball” label. They are what he calls an “invisible” part of postal history since so few pieces are available for study, let alone collection. “For obvious reasons, most items are kept as police evidence,” he says.

Though Speirs began collecting postal history in the 1980s, he became so engrossed in this inarguably dark corner of the hobby that, in 2010, he wrote a book on the topic titled The History of Mail Bombs: A Philatelic & Historical Study. Published by The Wreck & Crash Mail Society, which is based in Leeds, England, The History of Mail Bombs introduces readers to the earliest known parcel bombs of the late 1700s; recounts the injurious, attention-getting tactics practiced by British Suffragettes before World War I; and revisits the bloody strategies employed by Theodore Kaczynski, a.k.a. the Unabomber, who killed three and injured several dozen during an 17-year parcel-bombing spree at the end of the 20th century.

A stained postcard postmarked December 6, 1912. When the postcard was eventually sent to the recipient, it was accompanied by a note from the postmaster that explained it has been “soiled by fluid put into letter box by Suffragettes.” (Collection: Norman Watson)

Statistically, parcel and letter bombs, including those booby-trapped with the toxic bacteria that give a recipient anthrax, remain infrequent aberrations, but during the 20th century, these insidious devices have popped up more than you might think. “Mail bombs were rare until the 1900s,” Speirs explains, “so police did not have standing policies on how to deal with them. In my searches through old newspapers and magazines, they were treated as isolated incidents.” As a result, it has only been relatively recently that law-enforcement organizations have been able to identify the patterns in mail-bombing techniques and prepare accordingly.

Thanks to his research, Speirs was able to see the patterns, and his book is loosely organized around them. Some sections focus on the types of bombs, from parcels and letters designed to explode when opened to biochemical bombs designed to spread anthrax. Others delve into the sorts of people who commit these crimes, from those who hold personal grudges against a particular addressee to activists trying to use postal violence to make political statements. Finally, there are the artifacts of these events, as well as evidence of steps taken to prevent them, encompassing the “bomb inspected” marks on envelopes, as well as pieces of mail that have been singed by fire or suspiciously stained.

Stains are an example of the less-lethal tactics of the British Suffragettes, who in 1912 and 1913 launched a campaign of pouring bottles of ink or potassium permanganate into London mailboxes (called “pillar boxes” in the U.K.), which left letters and parcels covered with deep purple splotches. This was a nuisance, but it got the Suffragettes some ink, if you will, in their drive to gain the right to vote.

The sideways mark in red on the front of this envelope addressed to U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig shows that it was “X Rayed for Safety” on May 7, 1982.

Other actions taken by the Suffragettes were not so benign. According to Speirs, Suffragettes would stuff envelopes with fragile glass tubes that were filled with liquid phosphorous. When the tubes inevitably broke, the compound would burst into flames, injuring postal workers or mail sorters, without regard to how they may have felt about a woman’s right to vote. In the event, doing actual physical harm to innocents may have harmed the cause: British women would have to wait until 1928 to cast votes for candidates in elections, while women in the United States were granted the same obvious right in 1920.

Several sections of Speirs’s book focus on Kaczynski, who used the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) to deliver bombs to the homes and offices of academics, an airline president, and a timber-industry lobbyist, all of whom were apparently symbols of Kaczynski’s antipathy for industrial society (the “un” in the Unabomber’s name is short for “university”; the “a” stands for “airline”). In one instance, Kaczynski managed to get a bomb aboard an American Airlines flight. Police would later determine that the bomb contained enough explosives to bring down the plane, but bad wiring on Kaczynski’s part caused it to spew smoke instead. Ultimately, only a dozen passengers were treated for smoke inhalation.

Given his beef with technology, it’s somewhat ironic that Kaczynski was so adept at manipulating one of industrial society’s most elaborate creations, the postal system, to deliver his bombs. “Kaczynski was one of the most successful bombers because he varied his method of operation,” Speirs says, “which made it more difficult for police to investigate him.” Still, Speirs’s opinion of a particular criminal’s effectiveness should not be mistaken for even grudging admiration. “They are no better than terrorists who fly hijacked passenger jets into buildings,” Speirs says flatly of Kaczynski and his ilk.

On November 16, 1979, the Unabomber got a bomb aboard American Airlines flight 444 from Chicago to Washington, D.C. Though the bomb did not detonate, it did smoke, causing damage to mail and delaying delivery, as explained in this letter to a recipient from Postal Inspector T. J. Koerber. (Collection: Steven Berlin)

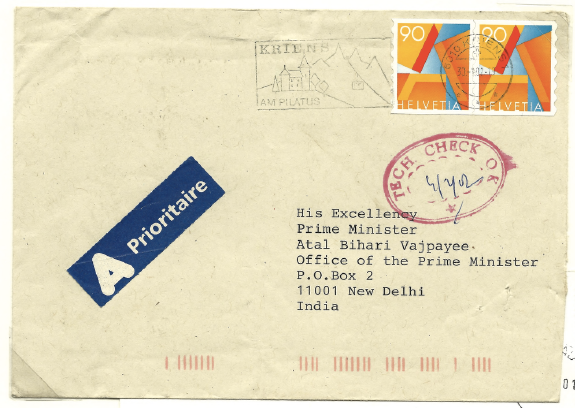

Today, in the United States, anyway, it’s generally more difficult to send something nasty through the mail than it was in Kaczynski’s heyday. For example, if a parcel is deposited in a corner mailbox with no return address but a lot of stamps on it, it’s not likely to get to its destination. Mail addressed to government officials in Washington, D.C., is routinely irradiated to kill live bacillus anthracis spores, while letters and parcels bound for sensitive government facilities such as the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee pass through some form of X-ray machine before they land on a recipient’s desk.

Still, according to Speirs, a glaring loophole has persisted long after Kaczynski was incarcerated, and even after heightened anti-terrorism measures were put in place by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security post-September 11, 2001. The loophole concerns packages weighing more than 13 ounces, which must be presented to a retail postal clerk rather than being dropped in a street-corner letterbox, even if they have proper postage. “The idea was to force a face-to-face meeting with a postal clerk or letter carrier,” Speirs says.

Unfortunately, postal customers who ignore this rule, or who are simply unfamiliar with it, routinely receive their parcels back in their own mailboxes marked “Return to sender,” as many legitimate USPS patrons have found out. For Speirs, this raises a troubling prospect: “Mail bombers obviously do not put their real return addresses on a package” he says. “The Unabomber used this method to aim at two targets with one bomb; if his package was not delivered, then it would be ‘returned’ to another victim.”

(All images via The Wreck & Crash Mail Society)

Flying the 'Freak' Flag: Documentary Will Reveal Why You Should Care About Stamps

Flying the 'Freak' Flag: Documentary Will Reveal Why You Should Care About Stamps

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You Flying the 'Freak' Flag: Documentary Will Reveal Why You Should Care About Stamps

Flying the 'Freak' Flag: Documentary Will Reveal Why You Should Care About Stamps John Hotchner Exposes Philatelic Errors, Freaks, and Oddities

John Hotchner Exposes Philatelic Errors, Freaks, and Oddities Errors Freaks and OdditiesErrors, freaks, and oddities sound like judgmental characterizations, but f…

Errors Freaks and OdditiesErrors, freaks, and oddities sound like judgmental characterizations, but f… US Stamp CoversStamp covers are perhaps the most tangible examples of postal history, whic…

US Stamp CoversStamp covers are perhaps the most tangible examples of postal history, whic… StampsThe world’s first adhesive postage stamp was the Penny Black, printed for t…

StampsThe world’s first adhesive postage stamp was the Penny Black, printed for t… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.