A children’s workbook cover from Italy, c. 1900.

There’s a reason that “Anne Frank: Diary of a Young Girl” remains one of the top nonfiction books of all time, with more than 30 million copies sold: Readers are moved by Frank’s intimate chronicle of ordinary youthful pastimes amid the unfolding of a historic genocide, her daily follies and dramas laid stark against a backdrop of violent ethnic cleansing and the inescapable death sentence we know awaits our young heroine.

“What interests us are the voices of the children of the past.”

The authentic voice of an adolescent living through a horrific moment in history speaks to people of all ages, but is especially resonant with kids. Children who may have a hard time relating to traditional history lessons, with their emphasis on memorizing timelines and key figures in eras that stretch for centuries, can quickly connect to past events when related from a peer’s perspective. So what if there were a better way to teach children about other times and places via those who actually lived there?

With the Exercise Book Archive, a collection of children’s composition books dating from the 18th century to the present, the Milan-based nonprofit Quaderni Aperti hopes to bridge this gap between the children of yesterday and today. Thomas Pololi and Anna Teresa Ronchi, founders of the organization, started this archive of overlooked books because of their passion for the writings of youth—texts that are direct, unvarnished, and created by a child’s own hand.

Pages in a student notebook from Unquillo, Argentina, c. 1952. “Poor canary! For days and weeks, he had cheered up our patio. He was the most popular. The one with the chocolate-colored speck on the head. And this morning, gathered around his cage during recess, we noticed he was not on the hammock where we’d always find him.”

The archive includes everything from the mundane to the profound: One girl’s notebook describes the bombing of her small town in 1940s Switzerland; another boy’s journal chronicles daily life in rural Pennsylvania during the 1890s; the diary of a Chinese teenager recounts his experiences in prison during the 1980s. Organized in a reverse chronology, the Exercise Book Archive’s website features high-quality scans of several such workbooks from around the world, though many more await digitization, transcription, and translation into English. The site also lets visitors to jump at random into the content of a specific children’s book, allowing for more spontaneous discovery.

Some of the writings are clearly more tedious exercises or handwriting practice assigned by parents or teachers, while others capture more unscripted details of daily life that are important to the kids themselves. Taken as a whole, the collection is a happy reminder of the universality of childhood across the globe, while also documenting the shifting role of formal education and the influential power adults have over the views of youngsters. We recently spoke with Pololi about the writings in the collection and their appeal to readers of all ages.

In this girl’s journal, she describes fleeing the Nazi invasion of France in 1940. “Since Friday night of June 14th, we’ve done nothing but go to the shelters. On Saturday, all the schools throughout France were closed. The soldiers were evacuated from Belfort to make it an open city. This piece of news stirred everyone. We saw many cars pass loaded with mattresses. Many people were sending parcels to the train station, which swarmed with cars and people, and that’s what made us leave at 6 a.m. towards an unknown direction.”

Collectors Weekly: How did this collection get started?

Thomas Pololi: In 2004, I began asking Italian friends for their childhood exercise books or the exercise books of their relatives. I started a blog where I published the contents of these exercise books, and when the blog got some attention, the project started to grow. Along with other people I met, we created the nonprofit organization Quaderni Aperti (“Open Exercise Books”). We started thinking about activities we could develop using the contents of the books, and started doing readings of the compositions and some workshops with kids, because we like to have them meet the former kids who wrote in these notebooks.

“You can imagine what you’ll find in a kid’s book, but when you read what is actually written inside, it’s not what you expect because of the singularity of every child, every life. It’s always a surprise.”

In 2015, we created an exhibition about the Italian content collected up to that point. Around the same year, we started collecting notebooks from other countries. We already had some of them—French notebooks, I think—and found them very interesting. So we were curious about what we could collect from other countries. It’s not been easy, but over the years we got better at finding interesting material. With the help of people living in other countries, we even found books from the Soviet Union and China. Then, the problem became how to understand and translate what was written inside. That’s the phase we’re in now.

What you see online is like one-fifth of the archive, and we just started to upload the interior content of those books. The full work may take several years to be completed, and meanwhile, we’re collecting other materials. We hope, with the help of volunteers and the financial support of companies or foundations, to speed up this work and to upload more and more content in the next few months.

Pages in a fourth grader’s essay book from Yantai in Shandong, China, c. 1930s. “I am reading newspapers at school. Firstly, I read our own newspaper, Shandong Daily. Reading the newspaper helps me make progress. I also teach other primary school fellows how to read newspapers from all over China. First I tried to talk to myself and learnt how to teach. Only in this way would my teaching to other fellows be successful. When I was giving a lecture, I said everyone can be a good newspaper teacher.”

Collectors Weekly: How exactly do you define an exercise book?

Pololi: Well, it’s not that easy because in different countries, these notebooks are called different things. For example, in the U.S., I think they’re called “composition books” more commonly. But in the British-speaking world, they are called “exercise books.” So we decided on exercise books because there are more countries in which they are called that. For our organization, “exercise books” include all the notebooks used by children in school, outside of school, and for homework.

This composition book from Buffalo, New York, c. 1938, belonged to an adult Polish immigrant applying for U.S. citizenship and beginning her studies at the elementary level.

We are especially interested in youth compositions, or the original testimonies that these books contain, so we focus on books that include diaries or materials like letters or drawings. We can’t understand much about children from a notebook with only mathematics exercises; what interests us are the voices of the children of the past.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the educational trends captured in the archive?

Pololi: I’m not a professional educator so my knowledge about education grew in making this project. But you can see that there was a similar evolution in many countries during the 20th century. The biggest change happened at the turn of the 19th and the 20th centuries as the movement of progressive education started to spread all over the world—in the U.S. with John Dewey or in France with Célestin Freinet; in Italy with Maria Montessori; in Switzerland with Johann Pestalozzi; in Austria with Rudolf Steiner. There was this movement of progressive educators who started to put the child at the center of the process of learning instead of a passive subject of teaching. This change was common in many countries across the world.

A passage in this book by a second grader in Buenos Aires, Argentina, reads: “Mr. Brown, owner of the building, gave us a wonderful present. Eighty sprouts of trees. Our teachers explain to us how we must plant them. Let’s get to work! In a few years we will walk in the shadow of beautiful paradises. But—I say to my mother—when these trees are grown, I will not be in school anymore. That is indeed true—said my mother—but it is also nice to sow things so that others can enjoy them.”

Collectors Weekly: How is this shift apparent in the composition books?

Pololi: Most of the notebooks are from the 20th century, so they are already into the second wave of this change. But we have some notebooks from the 19th century and even one from the 18th century. And you can see that before, there were mainly exercises of calligraphy with dictated sentences about how you have to behave in your life, with phrases like “Emulation seldom fails,” which means that if you emulate or if you imitate other people, you won’t fail in life. It implies that if you are yourself, you risk failing. That’s the opposite of what we teach children nowadays.

Older notebooks, like this one from Chester County, Pennsylvania, c. 1889, tend to feature less creative assignments than later examples.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the memorable historic moments recorded in these books?

Pololi: There are many historical periods narrated in the books from the point of view of children. It’s poignant because you have this contrast between the innocence of children and the drama happening around them. This is especially true of compositions about war, propaganda, or political events that we now recognize as terrible. But in the narration of children, there is often enthusiasm about the swastika in Germany, or the Duce in Italy (dictator Benito Mussolini), or for Mao in China. It is quite impressive because we know what happened, but reading the personal words of children is an immersion in the period and the daily life of children in these contexts. In most cases, the children tended to see the positive side of traumatic things, perhaps because their main goal is to grow up, and they needed to do it the world they lived in.

Excerpts from an Italian refugee middle schooler’s notebook dated February 7, 1945, and titled “The Flag on the Bell Tower.” “A few days ago, they raised the beautiful Swiss flag on the bell tower of Ligornetto. They put it up there as a signal to foreign planes that are on the neutral territory of Switzerland. Because a few days ago they strafed and dropped bombs on the Swiss territory of Chiasso. They said it was a mistake because with all the snow they could not see the Swiss flags. But since this mistake has been repeated several times it was thought to put the flags on the bell towers and on the important buildings.”

Collectors Weekly: How do these children’s writings reflect the politics of different eras?

Pololi: In most cases, the children seem really passive and just absorb the messages from their teachers or the propaganda that surrounds them. (Teachers were often forced to spread propaganda against their will.) You can see the children hailing national leaders, and you can imagine what’s going to happen to them in the future because they are trained to be enthusiastic about sacrificing for their country. It really makes you think, because when those children did grow up, many went to fight against other countries and died.

Collectors Weekly: Were the books’ designs influenced by politics as well?

Pololi: Yes, that happened especially in certain countries. For example, in Germany, the exercise books have always been very minimalist, so you don’t see propaganda on the covers of the books. They didn’t use a lot of very colorful books, while in other countries such as in Spain or in China, you see beautiful illustrations of propaganda themes. They are often aesthetically appealing because they were meant to persuade children to do or think something.

The cover of an elementary-age student’s composition book from China, c. 1970s. Inside, one passage reads: “During this summer vacation, I will do my homework, I will comply with national policies and regulations, I will help my family reduce the burden, and finally I will strictly keep up with my demands.”

Collectors Weekly: Do the workbooks indicate the wealth or status of their owners?

Pololi: We can see a big difference when we look at notebooks from some countries, like those under the Soviet Union. In the ’60s and ’70s, compared with Western countries during the same period, you see that in the Soviet Union, the workbooks were designed very poorly with cheap materials and the cut was not perfect. Even today, you can recognize the books coming from poorer countries.

“You have this contrast between the innocence of children and the drama of what’s happening around them.”

There are also differences between the notebooks of wealthy children and poor children of the same country, though it’s not always easy for us to understand if a notebook was used by wealthy child or a poor child. We have to explore the contents in detail, but they don’t always write about their family or their social position.

But the daily life of children from different countries, when there is not a huge disparity in wealth, is similar. They talk about the same things, about childhood things, and these are familiar all over the world. We often have more in common than we think.

Books from the former Soviet Union tend to be more cheaply made, like this one from Belarus, c. 1958. In one excerpt, the author writes: “In the summer we lived in the pioneer camp. Nearby there was a wide river. They made me a uniform. In the garden there are figs and apples growing. The fragrant May lily is nice.”

Collectors Weekly: Many of the assignments or exercises seem very similar despite coming from places with very different cultures.

Pololi: Yeah, absolutely. The topics of the compositions are similar, and most of the time they are about daily life, about what you see on the way to school or what you’ve done during the holidays. These types of things are common in many countries.

But you can clearly see when children live under a totalitarian regime, like in the Soviet Union or in China, because what they write is influenced by the propaganda of the moment. So in China when a child speaks about the things that he sees when he comes to school, maybe he describes a peasant he met who told him that we all have to work together for the country. Sometimes, it sounds ridiculous because they use these prepackaged sentences while they’re writing about a walk to school, but this is the effect of propaganda.

The writing in this book from East Germany, c. 1949, is clearly influenced by politics. “Health is a force that brings joy to our lives and enjoyment to the workplace. Loss of happiness and a worker’s disability are one and the same, the consequences of which are an inability to work, unemployability, a loss of one’s independence in life, and the introduction of health and disability insurance cover (a pension). One’s health is no inexhaustible resource and everyone is obliged to do their upmost to maintain and improve their own health. Young girls have carry a particularly big responsibility towards their own health as eventual wives and mothers to be.”

Collectors Weekly: Are there other notable differences in exercise books from different eras or parts of the world?

Pololi: Well, the calligraphy is something that you notice immediately. When you open a book from the beginning of the 20th century, you see beautiful calligraphy. That’s why many calligraphers follow the project, because they are interested in this aspect of the books.

Collectors Weekly: What’s the oldest workbook in the archive, and where did it come from?

Pololi: The oldest ones are from the U.K., and the oldest of those is from 1773. It’s filled with sentences about behavior written in very beautiful calligraphy, but the content is demoralizing. There is a lot of handwriting work and not a lot about the daily life of the children.

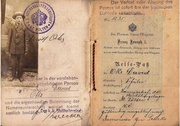

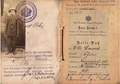

A printed engraving dominates the cover of the oldest book in the archive, which is from the the United Kingdom and dates to 1773.

We also have some older writings from the 19th century. In the U.S., children used to write journals, and we have some diaries from Pennsylvania and Connecticut written by children living out in the country. They speak about the harvest, helping their parents in the home, going to church on Sundays. The descriptions are not very rich; they are quite minimalist, as if the children didn’t have a lot of time to write in their diaries.

Collectors Weekly: Were you shocked or surprised by any of the writing in these books?

“They mention these big ideals while they’re writing about a walk to school, but this is the effect of propaganda.”

Pololi: Not really shocked, but surprised and moved, yes, very often because you can imagine what you’ll find in a kid’s book, but when you read what is actually written inside, it’s not what you expect because of the singularity of every child, every life. It’s always a surprise.

I remember one book from China in the 1980s written by an 18-year-old boy, which contains descriptions of life in prison. He doesn’t tell why he was in prison, but at some point, another prisoner tried to escape because he had a death sentence. The personnel of the prison asked all the prisoners to go and find this fugitive. And the boy found him and convinced him to surrender and go back to the prison because they may grace him; they may not condemn him to death. He is very happy about what he has done, about his work convincing this fugitive to return.

In this notebook from Bergamo, Italy, from 1978, a student wrote about a fight in the classroom. “Suddenly I rush towards Stefano and it seems to me that this is the real struggle. He throws his right fist into my belly and it hurts, but I grab him by the collar and pull him up and down the ground aggressively. Then I pull him again, but I am stopped by a child who trips me and takes me by the collar, dividing me from Stefano.”

Collectors Weekly: What has the reaction been at the workshops you’ve done with kids today?

Pololi: At the first sight of the inside of the exercise books, they were all surprised by the calligraphy—they couldn’t believe it was written by children. Even adults today don’t write like that. Speaking about the content, they were very curious and surprised to hear the compositions of children who lived during periods of war because for most of them, war is just a word. They can’t really understand what it’s like to live through.

A Japanese workbook cover from the 1960s.

They asked a lot of questions, and that’s why we organized meetings between the children and the original authors of these compositions who are still alive, so they could expand the narration and to bring their life testimonies to today’s children. Many authors of the exercise books didn’t remember the things they had written in the books when they were children, so it was also interesting because of the memories coming out while they were reading the books.

Collectors Weekly: What do you think is important to take away from the archive as a whole?

Pololi: I think the most important thing that emerges is the influence that adults try to have on children. Even nowadays, in a subtler way, adults try to mold children and make them adapt to the society they live in.

Children are subjected to our authority and the authority of teachers, and their ideas are very influenced by what we tell them and what we teach them, so we should probably be more careful and responsible about what happens in school and also in family life. Looking at the notebooks of the past, you can see it more clearly, this relationship between children and adults.

An excerpt of a letter to a friend in a composition book from Campo Grande, Brazil, c. 1932. “Dear Any, You asked me to leave something written especially for you. What do you want me to tell you? The deepest feelings are the ones that can’t be translated into words. Four years we were together—four years of dreams…of hope…of happiness!…Now, everything must pass. That happy collegial time will only remain poignant, aching nostalgia!”

Collectors Weekly: If someone wants to help translate part of the archive, what’s the best way for them to reach out?

Pololi: We designed the website to let people subscribe and become transcribers or translators of the content because the cost of transcription and translation is very high. We launched a recruitment campaign some weeks ago and now we have more than 100 volunteers from around the world helping us. Still, we especially need volunteers from Eastern Europe—places like Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, and Belarus—as well as Russia and China.

Anyone who wants to volunteer can fill out the form and subscribe as a volunteer. Volunteers choose the languages that they can transcribe or translate, and they will automatically be given access to the contents of the books they want to translate. We also send updates to the volunteers when there is more content added that they can work on.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Who Were the First Teenagers?

Who Were the First Teenagers?

Abandoned Suitcases Reveal Private Lives of Insane Asylum Patients

Abandoned Suitcases Reveal Private Lives of Insane Asylum Patients Who Were the First Teenagers?

Who Were the First Teenagers? The Politics of Prejudice: How Passports Rubber-Stamp Our Indifference to Refugees

The Politics of Prejudice: How Passports Rubber-Stamp Our Indifference to Refugees Childrens BooksIt wasn’t until the 18th century that books were written specifically for c…

Childrens BooksIt wasn’t until the 18th century that books were written specifically for c… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.