Without a doubt, black-velvet painting lives up to its reputation as the pinnacle of tackiness. You could point to any number of cheap, poorly done images of Elvis, scary clowns, matadors, “Playboy” nudes, and strange unicorns sold to American tourists by Mexican painters starting in the ’50s. But when velvet collectors Caren Anderson and Carl Baldwin look at these pieces, they see something else.

“Most velvet paintings are things that somebody wanted to pay money for, but sometimes you think, ‘Gosh, what is it?’”

Staring at a black velvet painting makes you feel “like you’re coming out of the womb,” says Anderson, who co-wrote the 2007 book Black Velvet Masterpieces with Baldwin. “It could also be described as if someone is walking toward you from a dark corridor. Either way, you’re in this dark place, and then things pop out at you.”

They have an air of mystery, agrees Baldwin, who’s also her partner at the Velveteria museum, which will reopen in Los Angeles as the Velveteria Epicenter of Art Fighting Cultural Deprivation on Dec. 13, 2013, nearly four years after the original location in Portland closed. “The light out of the darkness is really what it is,” he muses. “It’s a powerful medium. Something about it just grabs people by the short hairs.”

Top: In the 1970s, matador paintings were popular with American tourists, who were looking for a souvenir that “felt like Mexico.” (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art) Above: A tiger burns bright in a 1970s velvet by Pogetto. (From the Velveteria collection in Black Velvet Masterpieces)

And like any other art medium, velvet has its masters. Take Edgar Leeteg, who created sensuous, tropical paradises in the ’30s and ’40s using a dry brush to delicately paint each hair. By the ’60s, a Leeteg went for five figures, and if there weren’t so many replicas, they might still be worth a pretty penny.

But the tacky, flashy, and downright ugly paintings have stayed with the popular imagination—because, according to folklore scholar Eric A. Eliason, we need them to. In his 2011 book Black Velvet Art, Eliason suggests that velvet paintings play an important role in Western culture as the anti-art, a fixed concept that people distance themselves from to prove they have good taste. Even though velvet painting references the same sort of pop-culture icons—such as Marilyn Monroe, the Pink Panther, comic panels—as work by Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, and Roy Lichtenstein, it lacks the detached self-awareness that allows Pop Art to be deemed gallery worthy.

“Why is black velvet different than any other medium?” Eliason says. “Canvas art has some crappy and tacky stuff, too. But the assumption is the minute you put an artwork on velvet, you’ve ghettoized it into this denigrated category that, I think, exists for a purpose. If black velvet didn’t play the role that it has in the late 20th century, something else would’ve emerged to take its place. This snobbery shows the ugly side of the fine-art world and upper middle-class aspirational sensibilities.”

Two unicorns in love touch horns in this painting from The Velveteria. (Courtesy of Carl Baldwin)

In “Black Velvet Masterpieces,” Anderson tackles the long but patchy history of velvet painting, Baldwin contributes a more personal take, the story of how he fell in love with these artworks and Anderson at the same time. It’s the giddy peak of a carnival ride through his adventures in growing up in Southern California surrounded by surf rock, hot rods, head shops, boardwalk sideshows, and “Playboy” magazine.

“It’s a powerful medium. Something about it just grabs people by the short hairs.”

For Baldwin, velvets were simply part of the fabric of ’60s Southern California, where he grew up a rascal on the beach. Even though he and Anderson went to the same high school in Balboa, California, near Newport Beach, Baldwin didn’t take his “Coppertone Girl” on a date until they reconnected after their 25-year reunion. In 1999, Anderson visited Baldwin in Tucson, Arizona, where he owned a house.

On their way back from a day trip to the historic Wild West town Tombstone, they stopped at junk shop in Bisbee, where they saw, “a velvet painting of a kneeling woman with a big blue Afro across from a picture of John F. Kennedy. It was one of those creepy velvet paintings; his eyes would follow you all around the store. The painting of the woman was 29 bucks and Kennedy was a hundred, so we just went for the lady. We walked out feeling like a million bucks.”

Religious images have been painted on velvet since the Middle Ages. During the 20th century craze, Jesus was still the No. 1 figure seen on Mexican velvets, followed by Elvis, as seen on the painting at right by Argo. (Photos by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

This was the pair’s first step down what Baldwin calls “The Velvet Trail” that took him up and down the coast, around the Southwest, and over the border to Mexico to unearth velvets and their history. Eventually, Baldwin moved to Portland to be with Anderson, and the couple’s obsession soon filled their home. At this point, they’ve collected about 3,000, though only a few hundred of these will appear in the Velveteria at any one time.

“We’ve lost count of the velvets,” Baldwin says. “We’re just out of hand, totally insane. You know how it is in collecting: You just can’t stop. There’s no Betty Ford Center for it. We do get a little more selective. I’ve got nothing against the Lord, but we’re getting way too many Jesuses. Still, if it’s a good one, we’ve got to get it.”

Like Baldwin and Anderson, Eliason, a professor of English at a Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, is on a mission to prove that black-velvet painting is museum worthy. He believes they should be classified as “folk art,” because it is created by regular people with no formal art training. But scholars have traditionally “gone after easy, low-hanging fruit like a well-played Appalachian fiddle tune or a gospel-choir performance. So I had the thought, ‘What would be the most difficult case to make?’ And immediately the iconic black-velvet painting of Elvis struck me. Of course, part of the fun of this challenge is playfully and gently poking a finger in the eye of my discipline for having overlooked this art form for so many years.”

A giant cricket, Heaven’s Gate cult leader Marshall Applewhite, and Yoda hung near a room of religious art in Portland’s Velveteria. (Via Velveteria.com)

For what it’s worth, velvet is a difficult fabric to paint well. “Artists are often secretive about how they do it. In the Tijuana and the South Pacific traditions, it’s very much about using a light touch, which is hard to do,” Eliason says. “They say it’s easier to paint on canvas until you get the technique down. But the thing that makes black velvet better to work with is that you have the negative space and the shadows already there.”

“The G.I.s were teenagers, man. Their taste was not that sophisticated when it came to art, so they went for the naked ladies.”

What we know about the origin of painting velvet is spotty at best. The 13th-century merchant traveler Marco Polo recalled seeing painted velvet portraits of Hindu deities like Vishnu and Ganesh in India. Soon, Europeans were painting saints and allegories on the “sacred” fabric of velvet to hang in churches instead of woven tapestries. This practice was particularly popular with Russian Orthodox priests in the Caucasus Mountains. In the 1500s, Spanish conquistadors brought velvet to the Philippines and Mexico, where peasants in Jalisco created the custom of painting on velvet skirts and party dresses, which modern-day Mexican painters often cite as the roots of their tradition.

The road to mass-produced velvet paintings might have been paved by Victorians, when Francis Townsend’s concept of “theorem painting” became a hobby for middle-class ladies in England and the United States. This paint-by-numbers-type activity involved using stenciled patterns and brushes to paint pleasant things likes still lifes, flowers, and pretty landscapes onto velveteen, a cotton velvet imitation. Hand-painted velvet artworks, of familiar images such as scenes from “King Lear” or replicas of famous paintings like Georges de La Tour’s “The Fortune Teller,” were first mass-produced and sold in the United States by the New York-based FAMCO, or French American Manufacturing Company, in the early 1920s.

An Edgar Leeteg painting of a Tahitian child. (Courtesy of Brigham Young University Art Department Collection)

But what we think of as the modern tradition of velvet painting started with a scoundrel named Edgar Leeteg. A sign painter who was hit hard by the Depression, Leeteg went looking for work in Honolulu, Hawaii, and then Tahiti in the 1930s. On a quest for canvas, he ended up buying velveteen because a local store wanted to get rid of it. Remembering the religious velvet paintings he saw in St. Louis as a child, he worked to master this challenging material, which would cause thick paint to clump and later crack.

Around Tahiti in the 1930s and 1940s, Leeteg was a well-known drunk and bar-fighter, who hit on all the women using cheesy pick-up lines, when he wasn’t indiscriminately groping them. He painted flowers, landscapes, and children, but mostly the topless Polynesian beauties he bedded regularly and openly fetishized as noble savages with an Eden-esque innocence of their own sex appeal. In the early days, he was often low on cash, so he would trade his paintings for sandwiches and booze. Sailors and servicemen from the United States, who no doubt enjoyed his images as an escape from Western prudishness, would buy them for a few dollars.

But Leeteg was actually brilliant with the medium: He figured out how to paint thin layers with a nearly dry brush, keeping the hairs of the velvet separate. Using this layering technique, he was able to limit himself to seven colors, plus white, in oil paint. Despite his talent at creating lush landscapes and lifelike portraits, Leeteg was shunned by museums and art critics. Already, velvet was considered a tacky medium, and painting on velvet automatically precluded an artist from being taken seriously by the fine-art world, which enraged Leeteg.

A moonlit scene of a man and his canoe by Edgar Leeteg. (Courtesy of Brigham Young University Art Department Collection)

Despite this, Leeteg’s productivity never flagged, and he finished three paintings a month for 20 years, creating around 1,700 artworks in his lifetime. He often repeated himself and copied others. Seven of his most popular images were based on photographs that he didn’t take. Another one of his popular pieces was a replica of “The Head of Christ” by painter Warner Sallman, which Leeteg was forced to stop selling openly due to copyright law.

But Leeteg had his champions. In the ’30s, a Utah jeweler named Wayne Decker toured Tahiti on a cruise. In a Papeete shop, Decker spied Leeteg paintings on the wall, similar to ones he’d seen in Honolulu, and ran back to the ship to tell his wife about them. After he left, fellow passenger, Bob Brooks, the owner of the 7 Seas tiki nightclub in Hollywood, came into the store and bought all the Leetegs.

Desperate, Decker scoured the island looking for Leeteg until he found him, and when they finally met, Leeteg agreed to reproduce six of the paintings Decker had seen, including the famous “Hilo Hattie” and “Hina Rapa,” for five aloha shirts and $200. But those weren’t enough for Decker. He commissioned Leeteg to send him 10 paintings a year, and Leeteg fulfilled this agreement until his death in 1953. In the end, Decker had more than 200 paintings.

One of the many beautiful Tahitian women Leeteg painted. (Courtesy of Brigham Young University Art Department Collection)

Meanwhile, the 7 Seas bar, a competitor to Don the Beachcomber, was at the forefront of the burgeoning tiki-bar culture in the United States, which created an enticing, escapist fantasy of simple South Seas island life. Leeteg’s maidens, surfacing from the murky blackness of velvet, made the perfect backdrop for such places, and before long, tiki-themed bars and restaurants all over the United States, like the Tonga Room in San Francisco, just had to have a Leeteg.

During World War II, an influx of U.S. soldiers serving in the Pacific Theater discovered Leeteg’s work while on shore leave. The buxom, idealized women appealed to the young servicemen, who painted pin-ups on their plane nose cones and leather jackets. Leeteg’s popularity spurred a flurry or imitators, and Leeteg even taught his technique to a talented artist named Charles McPhee, who married one of Leeteg’s models, Elizabeth. The couple moved to New Zealand, where he painted her in a hugely popular series called “Tahitian Girl.”

But perhaps the most instrumental advocate of Leeteg’s work was an eccentric former Navy submariner, “Aloha” Barney Davis, who opened a gallery in Honolulu after the war, specializing in South Pacific art and artifacts. Customers kept coming in, asking for Leeteg’s velvets. When Davis finally tracked down Leeteg, he became the artist’s dealer, selling his paintings and licensing reproductions in his shop and all over the world. As tiki bars popped up in suburbs across the United States, the demand for Leetegs grew. Davis advertised Leeteg as the “American Gauguin” and tipped the press about Leeteg’s wildest exploits in Tahiti. (In New Zealand, Leeteg’s protegé McPhee became known as the “Velvet Gauguin.”)

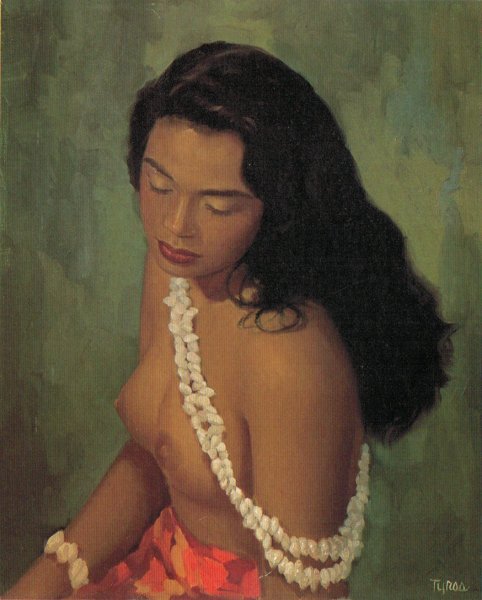

Ralph Burke Tyree’s “Local Girl,” circa 1950, is an example of the South Pacific school of velvet painting pioneered by Leeteg. (From Don Severson’s “Finding Paradise: Island Art in Private Collections,” via WikiCommons)

By the 1950s, demand for Leetegs was so high, the painter had a hard time keeping up. With his paintings were then selling for thousands of dollars, he built a vast estate he called “Villa Velour” in Cook’s Bay, Moorea, for his mother, multiple wives, and children. When Leeteg learned he had a venereal disease in 1953, he went on a drinking binge in Papeete and crashed his Harley-Davidson. The 49-year-old artist died instantly.

Nostalgia for the tropical islands on the part of the men who served in World War II, and subsequent wars in Korea and Vietnam, ensured the continued popularity of Leeteg and his followers in the South Pacific school of velvet painting. One such talent was Ralph Burke Tyree, who began painting velvets of Samoan maidens in the ’50s. And when James A. Michener immortalized the late Leeteg in his 1957 collection of non-fiction short stories, “Rascals in Paradise,” calling him, “at least the Remington of the South Seas,” Leeteg’s popularity skyrocketed. By the 1960s, an original Leeteg had sold for $20,000.

Thanks to Davis, velvet paintings became an essential part of the tourism industry in Hawaii, which became a state in 1959. When American artist Cecelia “Ce Ce” Rodriguez encountered a shop full of such velvet paintings in 1960s Honolulu, she was inspired to move to Hawaii and take up the medium. Lou Kreitzman sold her luxuriant artworks in his gallery and brought her paintings to be displayed in the Hawaiian pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. For years, several Hawaiian resorts proudly featured her work. But by the 1970s, the emergence of the Mexican velvet-painting industry killed the medium for Rodriguez, when even galleries in Hawaii stopped taking it seriously.

An ad for Aloha Barney’s Davis Gallery featuring velvet paintings from Leeteg of Tahiti. “Hina Rapa” can be seen in the top left corner. (Via MuseumofWonder.com)

Despite the thriving post-war economy, most Americans dreaming of far-away paradises couldn’t afford a trip to Polynesia, not even Hawaii. Mexico was the closest “exotic locale” for the American lower classes, and Mexican merchants were happy to play it up. In the 1950s, velvet paintings proliferated in tourist markets in cities all along the U.S.-Mexican border, including Ciudad Juarez, a town just across the border from El Paso, Texas, that was known as a place for Americans to ditch their Puritan roots and run amok.

“One person would paint the hair, the next person would do the collar, and the next person would do the rhinestones. The last person would do Elvis’s profile, and then it’d be done.”

In Juarez, Juan Manuel Reyna was one of the first artists to realize the medium’s potential when he bought a religious velvet painting of Jesus to restore in 1950. According to Black Velvet Masterpieces, he started painting his own works on velvet, and they were snatched up by tourists. In a 2004 “Houston Chronicle” article, Reyna told journalist Sam Quinones that in ’60s and ’70s, “a lot of people became velvet painters: housewives, students, unemployed men, everyone.”

Some people believe that soldiers shipping out of San Diego, California, brought velvet painting to the nearby border town, Tijuana, but Mexican artists will argue that their velvet-painting tradition began at home. Like Juarez, Tijuana, also known as TJ, had a long reputation as a city of sin and curios, going back to the 1920s, when Prohibition sent Americans south of the border in search of booze, prostitutes, and gambling. In the 1950s, velvet paintings joined the ranks of bullwhips, switchblades, and firecrackers as tempting souvenirs offered by Tijuana vendors.

“Back in the old days before Vegas became popular, TJ was the Las Vegas of the West Coast,” Baldwin says. “Hollywood would go down there for the jai alai, the race tracks, bull-fighting, gambling, and all the other bad things. Tijuana was basically the hell on earth.”

Tijuana artist Jesus “Chuy” Gutierrez took a photo of a neighbor with a craggy face in the 1960s and painted him as a bandido. This image as been replicated and altered hundreds of times by Gutierrez and his copycats. (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

Originality wasn’t a particular concern for Mexican velvet painters. If an image sold well, the painter would reproduce it over and over again, while his competitors would also copy it. Mexican border artists borrowed liberally from the South Pacific school as well as the Old Masters, photographs in magazines, and popular cartoons.

According to Black Velvet Masterpieces, Cesar Labastida was one of the early Tijuana velvet painters in 1954, supplying local store owners on Avenida Revolución with 40 paintings a week of matadors, Native Americans, Jesus, and celebrities, which the stores would then offer for $60 apiece. In the book, Miguel Mariscal tells Anderson he started painting John F. Kennedy after his assassination in 1963. “Not until celebrities died did people want these velvet images of them. Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Jim Morrison, John Lennon,” Mariscal explains.

But a living, breathing celebrity was even bigger than those. Moises Mariscal, in Black Velvet Masterpieces, asserts his father sold the first-ever black-velvet Elvis, or “Velvis,” from his Tijuana gallery in the ’50s. In the book, Miguel Najera says Elvis was where the money was in the 1960s and early ’70s, before the singer’s untimely death in 1977. Najera worked with Nicolo Pino, who, with his workers, churned out low-quality paintings of Elvis by the thousands.

To save time, Mexican velvet painters would often take a wet image and press it onto a fresh piece of velvet to create a lighter image to fill in. That’s why so many velvet images have mirror images floating around, as you can see with these poodle paintings. (From the Velveteria collection in Black Velvet Masterpieces)

To make the process go faster, the artist would lay a wet painting on a blank piece of velvet and press them together to create an outline for the next painting. That’s why so many velvet paintings have reverse images. Another technique for getting the outline on the canvas included punching small holes along the lines of a drawing, placing the drawing on the velvet, and then dusting it with chalk or light-colored powder, so that the chalk left a dotted outline on the velvet. (Sometimes you can still see part of the chalk outline on a velvet painting.) Images were also projected onto the velvet, or the painters would use techniques like airbrushing or screenprinting.

Because of this, some border painters had no artistic skills, but the velvet painters who have stuck with it usually have a real gift, such as Najera, Tony Maya, Roberto Sanchez, and Nacho Amaro, perceived to be among Tijuana’s best, according to “Los Angeles Times” reporter Sam Quinones. And Baldwin points to Daniel Guerrero in Nogales, Mexico, as a master of creating light in the blackness of the velvet.

No matter how much talent they did or didn’t possess, early Mexican velvet painters didn’t have the resources to concern themselves with artistry; they had to make a living. That’s why images that sold well—Jesus, Elvis, panthers, cowboys, clowns, bullfighters, dead celebrities, naked women—were copied over and over again. It didn’t matter if the paintings were done well or poorly, they sold the same. Mexican artists used cheaper acrylic paints and velveteen with a thinner nap than the velvet painters of the South Pacific school.

The kid who had this clown in his or her room probably had a hard time sleeping. (From the Velveteria collection in Black Velvet Masterpieces)

Besides celebrities and wild animals, the subjects of the paintings were often based on American fantasies about Mexico, which is why they featured campesinos, matadors, low-riders, and stunning cactus-dotted landscapes. In Quinones’ 2002 article “Velvet Goes Underground,” Tijuana artist Jesus “Chuy” Gutierrez remembers taking a snapshot of a neighbor with a rugged face in the ’60s and painting him as a Mexican outlaw, or “bandido.” This image was knocked off thousands of times and sometimes embellished with scars, cigars, eye patches, or facial hair.

Tourists bought black velvet paintings for their children’s rooms, often featuring clowns, unicorns, or cute kids and animals with big eyes and big heads. Paintings of dogs playing poker, based on 1903 advertising C.M. Coolidge created for Brown & Bigelow to sell cigars, were popular with fraternal societies and men’s clubs like the Elks Lodge. Often Christians took their religious velvets of Jesus, Mary, or the Last Supper very seriously. The spirit of the civil-rights movement was even captured and celebrated in velvets honoring Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Strange, alien-like children with huge eyes show up often on vintage velvets. (From the Velveteria collection in Black Velvet Masterpieces)

Other, less noble velvets reveled in vices and sophomoric humor. Children and devils were depicted sitting on the toilet, probably for display in the bathroom. Naked women with impossibly perfect bodies were a staple. “Dope art” celebrated drug culture, while psychedelic pieces were painted with Day-Glo colors to be used with black lights.

“Most of them are things that somebody at some point decided that they wanted to pay money for,” Eliason says. “But sometimes you think, ‘Gosh, what is it?’ Things like a poor, little girl with a pig nose and the dog that looks like it has stumps instead of actual legs. It’s just like, ‘Ahhh! What is that?’”

“Yeah, a lot of them were tacky, it’s true,” Anderson admits. “But Mexican artists painted what they thought we wanted or what people were buying. We laugh at some of those bad ones but I’ve heard people say, ‘Hey, I know people who still have them in their trailers.’ And there are a lot of Mexican people here in California and other places, who’ve got their Virgin Marys hanging in their homes, and it’s no joke.”

The struggles of the civil-rights movement and its leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, were captured in velvet. (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

During the Vietnam War, tourist-market black velvet painting also proliferated in Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines, particularly in Angeles City, near the United States’ Clark Air Force Base. In Black Velvet Masterpieces, Anderson says, “Wherever the U.S. military went, velvet painting seems to have followed.” A company called Suh Kwang Products Limited in Korea and Vietnam produced round velvet paintings with big-eyed soldiers, often with tears in their eyes, in front of jungle scenery or helicopters.

“This snobbery shows the ugly side of the fine art world and upper middle-class aspirational sensibilities.”

“During the Vietnam War in the ’60s, all the G.I.’s would go out from San Diego, through Hawaii, and then to Angeles City in the Philippines,” Baldwin says. “That was the R&R place they’d go to from ‘Nam. Over the course of doing this research, I met quite a few guys who went to Angeles City brothels. It was just a wild, wild place, thanks to all these young guys fighting in the war. And they were teenagers, man. Their taste was not that sophisticated when it came to art, so they went for the naked ladies. These guys would roll them up in their duffle bags and bring them back to the States.”

Baldwin remembers a man who came by, offering them a whole bunch of ’60s black-light paintings, which Baldwin purchased for display in the museum. “It’s heavy stuff about war and drug usage,” Baldwin says. “There’s this muscle-bound skeleton of a G.I. shooting up. He’s got the skull face and the Army helmet. And I go, ‘Shit, that’s Vietnam.’”

During the Vietnam War, these images of GIs as wide-eyed children by Suh Kwang Products Limited were snapped up by U.S. soldiers. (From the Velveteria collection in Black Velvet Masterpieces)

Despite all the street artists in Southeast Asia, Mexico was where the true commercialization of velvet paintings flourished. In 1964, an American business owner Doyle Harden, who owned a grocery-store chain in Georgia, purchased seven velvet paintings on vacation in Juarez. When he sold them at his stores, his profit covered the cost of his trip. After that, he returned to Juarez regularly to haul back truckloads of velvets. In the early 1970s, he formed a partnership with Chicago business Leon Korol, to establish Chico Arts to distribute black velvet paintings to five-and-dime stores all over the United States.

In 1972, Harden built a block-long Chico Arts factory, or “maquiladora,” in Juarez where he employed workers for round-the-clock shifts that produced several thousand paintings a day, distributed to American gift stores, malls, mobile-home dealers, and motels. Each painter would work with one color on his or her brush, and the painting techniques for each were highly guarded secrets, to discourage painters from opening their own businesses.

“The paintings would slide along these boards that the factory owner had constructed,” Eliason says. “One person would paint the hair, the next person would do the collar, and the next person would do the rhinestones. The last person would do Elvis’s profile, and then it’d be done. And then they’d slap the name of the patron or the factory owner on it, and out it’d go.”

This devil surround by vices is a part of the black velvet subgenre known as “dope art.” (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

Unfortunately, the workers suffered from breathing in the toxic fumes from the black leather dyes used to create outlines and cover up errors. In spite of that, the formerly impoverished factory painters were often happy to have the work, which allowed them to buy houses and cars, much like the artists working for themselves in Tijuana like Jorge Avalos. By the 1970s, successful velvet painters lived large, like modern-day drug dealers. Some of the most talented, like Enrique Felix, made their way to American tourist hotspots like Los Angeles or Las Vegas. Many blew their money on gambling, alcohol, prostitutes, pimped-out cars, and dirt-bike racing.

“I’ve got nothing against the Lord, but we’re getting way too many Jesuses. Still, if it’s a good one, we’ve got to get it.”

Meanwhile, Harden was amused and delighted that he was shunned in Southern high-society circles for mass-producing such tasteless working-class art. Before long, he had several maquiladora competitors, and distributors would buy these factory paintings to shill on American street corners. At the time, Mexican velvet paintings reached as far north as Alaska and as far south as Panama. In Canada, Pakistani vendors strapped these velvets to their backs and sold them door to door. An Armenian purchased Mexican paintings by the hundreds to sell in New Zealand, while an Indian man brought them to Trinidad and Tobago. In the 1980s, Scientologists bought paintings from Harden to sell on corners in the United States to fund their training.

According to Quinones, in 1979, Tijuana painters got so fed up with all the competition they formed the Quetzalcoatl Painters Union, which grew to 350, becoming a part of the ruling PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party). Around the same time, Tijuana cops started harassing street painter and vendors, so the union sought help from PRI leader Rafael Garcia Vazquez, who then faced threats within his own party.

Black velvet paintings of dogs playing poker, based on 1903 advertisements C.M. Coolidge created for Brown & Bigelow to sell cigars, often adorned the walls at Elks Lodges. (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

By the mid-1980s, a downturn in the Mexican economy, the rise of Wal-Mart, the spread of laws targeting street vendors, and a shift in tastes all came together to tank the velvet-painting market. That’s when Americans ditched their water beds, lava lamps, and velvets as vulgar relics of the disco era they wanted to forget. Most of the factories in Juarez, with the exception of Harden’s Chico Arts, shut down.

But velvet painting hasn’t completely died out. In the 1990s, China and India opened their own velvet-painting factories, cranking out similar paintings often signed with Mexican names. Even in Los Angeles’ Mexican neighborhoods, Baldwin says he now sees a different kind of velvet at the vendor stalls. “They have ones, like a Native American or cowboy on a horse, that say ‘Sanchez.’ I look on the back, and it says ‘Made in China.’ I go, ‘How many Sanchezes are there in China?’ India is putting this stuff out, too.”

Some of the most talented painters from Mexico like Felix, Gutierrez, and the brothers Juan and Abel Velazquez are keeping the techniques alive. Instead of Elvises, nudes, and matadors, current Mexican vendors are selling modern-day working-class icons like Al Pacino as “Scarface,” Tupac Shakur, Bob Marley holding a doobie, and Mormon founder Joseph Smith. Mexican consumers have started buying velvet paintings for themselves, and they’re particularly attracted to Aztec legends like the epic, tragic love story of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl.

Today, Mexicans are more likely to buy velvet paintings of Aztec legends, like the star-crossed love story of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl. (From the Velveteria collection in Black Velvet Masterpieces)

As art form, Anderson insists that black velvet painting is alive and well. “Young people are picking it up every day,” she says. Eliason believes black velvet paintings are ripe for ironic hipster appropriation, for “people who are like, ‘Ooooh, I’m in on the joke.’ But then I think there’s almost a post-ironic type of collector as well, who is like, ‘Yes, I realize that this is tacky or at least at one time considered so, and I guess I could be seen as ironic collecting some of these, but no, I just like them.’”

Still, people aren’t willing to put down the same sort of money they would for a work considered fine art. “I don’t understand it. If it’s a good painting, it’s a good painting,” Anderson says. She particularly enjoys talking to the people who come into the museum and share their memories, saying things like, ‘‘My grandma had that painting.” Anderson has even heard stories about families torn apart by fights over their velvet Elvis. “The people that collect, the people that paint, they’re a wacky bunch.”

No kidding. “One of the biggest collectors I’ve met is a guy named Rick Smith in Canada, who used to be a director of the Living History Park in Calgary,” Eliason says. “He got a terrible lung disease and thought he was going to have to have major surgery and probably die. In preparation for his surgery, the doctors put him on drugs that gave him this super attenuated focus on colors, which started tripping him out. He saw a black-velvet painting in a thrift store and just had to have it and hung it up in his room at the hospital.

Tupac Shakur is also a frequent subject of modern-day Mexican velvet paintings, like this work by Argo. (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

“When his friends came by and gave him a hard time about it, his response was, ‘Well, I’ll show them. I’m not just going to buy five more. I’m going to buy hundreds more.’ Then, he started doing a benefit, called ‘Rick’s Amazing Velvet Experience’ or ‘RAVE,’ to raise money for medical research. All of the high-society people of Calgary would pay to come to this thing, several hundred bucks a plate. Then he’d lead them into this room where he had this collection of 300 velvet paintings.”

In the early days of his “Velvet Trail,” Baldwin met velvet painter Daniel Guerrero, “one of the greatest I’ve ever seen,” and bought a bunch of his ’60s velvets at a dusty market in Nogales, Mexico, across the border from Nogales, Arizona. When Guerrero suggested he was only buying the paintings to resell them in the United States for more money, Baldwin replied, “No, I’m going to open a museum and write a book,” even though he had no idea that’s exactly what he would do. Last December, Baldwin returned to Nogales to present Guerrero with a copy of his book.

When the new Velveteria museum opens, for $10 apiece, visitors will be able wander through galleries focused on naked women, “toilet art,” and black-light painting. Baldwin and Anderson love creating sight gags, like pairing two images of John Wayne as Rooster Cogburn, each with the eye patch on a different eye. Then, they’ll add a caption like, “Look out! My third eye is the good eye.”

“It’s all about fun,” Baldwin says. “It’s all about sharing them with people and having a laugh in this cruel, awful world we live in.”

Tijuana painters often created soaring eagles to sell to patriotic Americans. (Photo by Scott Squire from Black Velvet Art)

(To learn more about black velvet paintings, check out Carl Baldwin and Caren Anderson’s book “Black Velvet Masterpieces,” Eric A. Eliason and Scott Squire’s book “Black Velvet Art,” and John Turner’s book “Leeteg of Tahiti: Paintings From the Villa Velour.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Tiki Hangover: Unearthing the False Idols of America's South Seas Fantasy

Tiki Hangover: Unearthing the False Idols of America's South Seas Fantasy

The Vintage Waiting Room Art That's Hooked the Shabby Chic Crowd

The Vintage Waiting Room Art That's Hooked the Shabby Chic Crowd Tiki Hangover: Unearthing the False Idols of America's South Seas Fantasy

Tiki Hangover: Unearthing the False Idols of America's South Seas Fantasy Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets Folk Art PaintingsAmerican folk art paintings came out of the relative lack of exposure artis…

Folk Art PaintingsAmerican folk art paintings came out of the relative lack of exposure artis… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Velvet painting alexander hunter