On November 7, 1885, when Canadian philanthropist Donald A. Smith drove a ceremonial last spike into his country’s transcontinental railroad at Craigellachie, British Columbia, almost 3,000 miles of tracks were finally joined as one. Given Canada’s immense size and inhospitable climate compared with its southern neighbor—whose shorter, 1,907-mile transcontinental railroad was opened in 1869—the completion of Canada’s transcontinental railroad marked the beginning of a vigorous global marketing effort to fill the nation’s vast, uninhabited spaces with people. This story of how graphic art was used to fulfill this Canadian version of Manifest Destiny is now the subject of a beautiful new book by Canadian-graphic-design authority Marc Choko. Titled Canadian Pacific: Creating a Brand, Building a Nation, the five-pound tome is available from Callisto Publishers GmbH.

Top: A Peter Ewart poster for rail travel, circa 1955. Above: A Norman Fraser poster promoting tourism in Nova Scotia, 1939.

“From the beginning,” Choko told me recently over the phone, “the directors of the Canadian Pacific decided to rely on graphic publicity to advertise their company’s activities. It was a conscious decision made very early on at the end of the 19th century. By the 1930s, CP was running its own silkscreen studio at the railway station in Montreal. Very few private companies do something like that, but print advertising was that important to Canadian Pacific.”

As Choko’s book amply illustrates, the posters and brochures produced by CP for its eventual network of railways, steamships, airlines, and hotels were routinely well designed—and frequently gorgeous. This should come as no surprise considering the caliber of artists the company employed, although not all of CP’s artists were necessarily widely acclaimed. The company also hired artists who worked in near anonymity at the time, and about whom even less is known today.

Norman Fraser poster promoting Canadian Pacific’s routes to Europe, 1939.

Norman Fraser, whom Choko describes in his book as “by far the most prolific artist commissioned by Canadian Pacific,” is perhaps the best example of this type of under-the-radar artist—it’s believed he lived in Montreal from 1930 to 1953. “We know almost nothing about this guy,” Choko sighs. “I’ve met quite a few old guys from those days, but nobody has ever been able to tell me anything about him, and I couldn’t find a trace of information on him in the CP archives. Until relatively recently, commercial artists like Fraser were totally despised by art historians, and they received no recognition of any type when they were alive.”

Fraser didn’t exactly make the job of piecing together a picture of his output at CP simple. “He didn’t sign a lot of his posters,” Choko says, “so we’ve had to guess that a lot of the posters that are marked with an ‘F’—and only an ‘F’—are his. He also worked in a number of very different styles, probably doing whatever the art director of the CP studio in Montreal was asking of him.” This combination of high output, varying styles, and lack of documentation like written contracts makes Fraser one of the Canadian Pacific’s most elusive and mysterious artists.

Peter Ewart’s first poster for Canadian Pacific, 1940.

Much more is known about Saskatchewan native Peter Ewart (1918-2001), who, Choko writes, knew in high school what he wanted to be when he grew up. Immediately after high school, Ewart studied at the Sir George Williams College in Montreal, the Art Association of Montreal, and the Commercial Illustration Studio of New York City, which promoted the avant-garde aesthetic being pioneered by E. McKnight Kauffer and Joseph Binder and practiced by Otis and Dorothy Shepard. Ewart’s first poster for Canadian Pacific, “Sports d’Hiver,” which was commissioned in 1940, is one of the company’s most iconic images. Over the next two decades, Ewart produced more than 30 more posters for CP, invariably of attractive people flashing big, toothy smiles.

Not all of the artists the CP employed were Canadian natives like Fraser and Ewart. Thomas Hall (1885-1972) and Charles James Greenwood (1893-1965) were both born in England, but lived most of their lives, and died, in Canada. “I like Greenwood,” Choko says, “for the way he changed his artwork completely from classical narrative paintings to modernistic posters suited to the silkscreen technique. Printing demands simplified lines and flat colors, as in his Alaska poster, with its green glaciers looming behind the little boat. It’s a good example, I think, of the impact a printing technique can have on an artist.”

Charles James Greenwood poster promoting cruises to Alaska, 1935.

Equally interesting to Choko is the way in which CP permitted other artists to stay true to their aesthetic rather than tweaking it for a particular technique or the fashions of the time. “Compared with what was happening in Europe in the 1930s,” he says, “the graphic sensibility in Canada and at Canadian Pacific was not especially up to date. But it was probably better for the type of clientele that the CP was looking for—sometimes modern posters can be more interesting graphically but not as effective. Take Thomas Hall’s bear poster, for example. Everybody liked that poster. It was not modern at all for the 1930s, but for people who were considering a hunting trip to Canada, it was a fantastically inviting poster.”

Part of the secret to Hall’s posters was the way he put viewers in the picture without portraying them. “When looking at the game posters he designed for Canadian Pacific,” Choko writes of Hall’s work, “it almost seems as if he depicted the animals from the perspective of a hunter, who is just about to pull the trigger of his gun.”

Thomas Hall’s iconic bear-hunting poster, 1938.

For Choko, this is the sort of detail that keeps the graphic art of the Canadian Pacific endlessly interesting. “I wrote my first book on CP posters with David Jones something like 25 years ago,” he says. “This new book is much more complete because in addition to posters, it covers brochures, timetables, menus, and other great examples of the CP’s graphic work. And newly rediscovered Canadian Pacific posters pop up every two or three months—the supply seems endless.” As big and as boundless, one might say, as Canada itself.

(All images courtesy Callisto Publishers. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

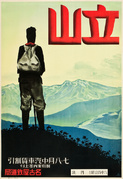

Mysterious Railway Posters Depict the Dreamy Allure of Deco-Era Japan

Mysterious Railway Posters Depict the Dreamy Allure of Deco-Era Japan

Double the Fun: The Husband-Wife Team Who Made Everyone Want to Chew Gum

Double the Fun: The Husband-Wife Team Who Made Everyone Want to Chew Gum Mysterious Railway Posters Depict the Dreamy Allure of Deco-Era Japan

Mysterious Railway Posters Depict the Dreamy Allure of Deco-Era Japan Circling the Globe With the Mid-20th Century's Most Brilliant Matchbox Art

Circling the Globe With the Mid-20th Century's Most Brilliant Matchbox Art Railroad Posters and AdvertisingAlmost immediately after the final spike was driven into the 1,912-mile Fir…

Railroad Posters and AdvertisingAlmost immediately after the final spike was driven into the 1,912-mile Fir… Travel PostersSince the 19th century, travel and transportation companies—including airli…

Travel PostersSince the 19th century, travel and transportation companies—including airli… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

OMG I love these especially the ones from east coast.

I renovated a CN caboose for a cottage and always looking for cool wall art.

I have five CPR posters from the 1930’s

Artists include Norman Fraser and Kenneth Shoesmith!!??

Funky