Household

Fashion

Jewelry

Ephemera

AD

X

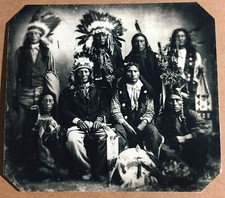

Antique Tintype Photographs

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

Tintype is the popular moniker for melainotype, which got its name from the dark color of the unexposed photographic plate, and ferrotype, named after the plate’s iron composition (for the record, tintypes contain no tin). Patented in 1856,...

Tintype is the popular moniker for melainotype, which got its name from the dark color of the unexposed photographic plate, and ferrotype, named after the plate’s iron composition (for the record, tintypes contain no tin). Patented in 1856, tintypes were seen as an improvement upon unstable, paper daguerreotypes and fragile, glass ambrotypes. In contrast, tintype photographs were exposed on a sheet of thin iron coated with collodion, which required less time to expose than albumen, but was still inconvenient inasmuch as the photograph had to be taken with the wet material on the plate.

Arriving just prior to the Civil War, tintypes became the favorite way for a soldier to capture his likeness before heading off to battle. Most Civil War tintypes were shot in a studio against a painted backdrop. In fact, so many of these tintypes were produced that the date and studio location of the image can sometimes be identified just because of the design of the backdrop. Tintypes were also popular with tourists at resorts and arcades, so much so that the medium persisted well into the 1930s. Other genres of tintypes include post-mortem photographs (a particularly Victorian preoccupation) and tintypes of paintings and other works of art, which is why tintypes are frequently used by art scholars researching late 18th- and early 19th-century artists.

The raw materials for tintypes were purchased by studios and photographers as 6½-by-8½ inch plates, with brand names like Eureka and Excelsior. These plates were then cut up into smaller sizes based on the whim of the customer. Because this task was performed in the studio or sometimes in the field, the dimensions and uniformity of tintypes can vary, with rounded corners being the most common deviation from pure rectangles. Many tintypes were also trimmed after the fact by customers, who would gladly sacrifice an edge or two to fit their tintype into an existing frame.

The smallest tintypes were called gems for their tiny (½-by-1 inch) size. These tintypes were so small, they were often secreted into lockets and worn by a loved one like a piece of jewelry. More common were what are known as 1/6th-plate tintypes, which are roughly 2¾-by-3¼ inches. Other studios would put your image on a tintype in the standard cartes-de-visites size (2½-by-4 inches), while wealthier customers would spring for ¼, ½, of full-plate tintypes.

The chief disadvantages of tintypes, other than the lack of a negative, was that the images they produced were dark to begin with and tarnished with age quickly. That’s why many tintypes were overpainted later, some in a folk-art style, others simply to brighten up old images. To preserve the images, tintypes were often encased in elaborate frames similarly to ambrotypes. A quick way to determine if an encased image is one or the other is to hold a magnet to the back of the case—if it sticks, you are holding a tintype.

Continue readingTintype is the popular moniker for melainotype, which got its name from the dark color of the unexposed photographic plate, and ferrotype, named after the plate’s iron composition (for the record, tintypes contain no tin). Patented in 1856, tintypes were seen as an improvement upon unstable, paper daguerreotypes and fragile, glass ambrotypes. In contrast, tintype photographs were exposed on a sheet of thin iron coated with collodion, which required less time to expose than albumen, but was still inconvenient inasmuch as the photograph had to be taken with the wet material on the plate.

Arriving just prior to the Civil War, tintypes became the favorite way for a soldier to capture his likeness before heading off to battle. Most Civil War tintypes were shot in a studio against a painted backdrop. In fact, so many of these tintypes were produced that the date and studio location of the image can sometimes be identified just because of the design of the backdrop. Tintypes were also popular with tourists at resorts and arcades, so much so that the medium persisted well into the 1930s. Other genres of tintypes include post-mortem photographs (a particularly Victorian preoccupation) and tintypes of paintings and other works of art, which is why tintypes are frequently used by art scholars researching late 18th- and early 19th-century artists.

The raw materials for tintypes were purchased by studios and photographers as 6½-by-8½ inch plates, with brand names like Eureka and Excelsior. These plates were then cut up into smaller sizes based on the whim of the customer. Because this task was performed in the studio or sometimes in the field, the dimensions and uniformity of tintypes can vary, with rounded corners being the most common deviation from pure rectangles. Many tintypes were also trimmed after the fact by customers, who would gladly sacrifice an edge or two to fit their tintype into an existing frame.

The smallest tintypes were called gems for their tiny...

Tintype is the popular moniker for melainotype, which got its name from the dark color of the unexposed photographic plate, and ferrotype, named after the plate’s iron composition (for the record, tintypes contain no tin). Patented in 1856, tintypes were seen as an improvement upon unstable, paper daguerreotypes and fragile, glass ambrotypes. In contrast, tintype photographs were exposed on a sheet of thin iron coated with collodion, which required less time to expose than albumen, but was still inconvenient inasmuch as the photograph had to be taken with the wet material on the plate.

Arriving just prior to the Civil War, tintypes became the favorite way for a soldier to capture his likeness before heading off to battle. Most Civil War tintypes were shot in a studio against a painted backdrop. In fact, so many of these tintypes were produced that the date and studio location of the image can sometimes be identified just because of the design of the backdrop. Tintypes were also popular with tourists at resorts and arcades, so much so that the medium persisted well into the 1930s. Other genres of tintypes include post-mortem photographs (a particularly Victorian preoccupation) and tintypes of paintings and other works of art, which is why tintypes are frequently used by art scholars researching late 18th- and early 19th-century artists.

The raw materials for tintypes were purchased by studios and photographers as 6½-by-8½ inch plates, with brand names like Eureka and Excelsior. These plates were then cut up into smaller sizes based on the whim of the customer. Because this task was performed in the studio or sometimes in the field, the dimensions and uniformity of tintypes can vary, with rounded corners being the most common deviation from pure rectangles. Many tintypes were also trimmed after the fact by customers, who would gladly sacrifice an edge or two to fit their tintype into an existing frame.

The smallest tintypes were called gems for their tiny (½-by-1 inch) size. These tintypes were so small, they were often secreted into lockets and worn by a loved one like a piece of jewelry. More common were what are known as 1/6th-plate tintypes, which are roughly 2¾-by-3¼ inches. Other studios would put your image on a tintype in the standard cartes-de-visites size (2½-by-4 inches), while wealthier customers would spring for ¼, ½, of full-plate tintypes.

The chief disadvantages of tintypes, other than the lack of a negative, was that the images they produced were dark to begin with and tarnished with age quickly. That’s why many tintypes were overpainted later, some in a folk-art style, others simply to brighten up old images. To preserve the images, tintypes were often encased in elaborate frames similarly to ambrotypes. A quick way to determine if an encased image is one or the other is to hold a magnet to the back of the case—if it sticks, you are holding a tintype.

Continue readingMost Watched

ADX

ADX

AD

X