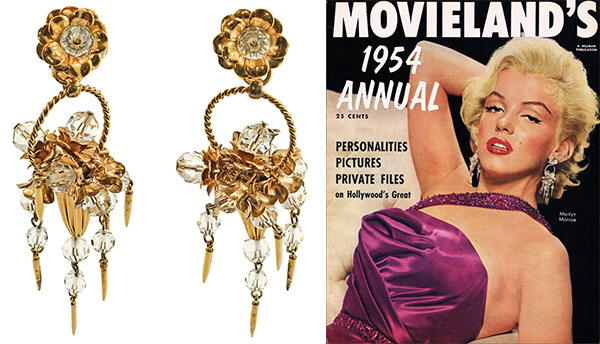

Marilyn Monroe wore Napier when she posed for the cover of “Movieland” magazine in 1954. That same decade, Mamie Eisenhower, Arlene Francis, Miss America, and the Duchess of Windsor all flaunted Napier. Doris Day even endorsed two namesake lines from Napier. “The brand was often on the cutting edge of jewelry fashion,” says Napier expert Melinda Lewis. “That’s why Napier was in so many fine department stores on Fifth Avenue, because it was a step ahead of the other brands, who followed its lead.”

Despite Napier’s past prestige, Lewis, a costume jewelry collector, could only find a few short paragraphs on the company online in the early 2000s. That just made her more determined to hunt down the real story of this forgotten brand. Lewis went on an 11-year quest exhaustively researching the company, interviewing a former president, Ron Meoni, as well as more than 50 former Napier employees. She went through company archives provided to her from former employees, as well as public records in Attleboro, Massachusetts—where Napier started as the E.A. Bliss Company in 1878—and in Meriden, Connecticut—where the plant operated from 1890 to 1999. (Jones New York bought the Napier name in 2000 and continues to produce jewelry under the brand.)

Top: Four hinged filigree bangles, from the late 1920s to early ’30s, made from gold-plated brass and glass stones. Above: The large floral-basket earrings Marilyn Monroe wore for the 1954 cover of “Movieland” magazine. (From “The Napier Co.”)

Now, Lewis’s detective work has paid off: This summer, Lewis, the co-founder of Costume Jewelry Collectors International, published an authoritative, full-color 1,000-page book on the company’s 125-year history, with an identification and price guide built in. Co-written with former Napier salesman Henry Swen, “The Napier Co.: Defining 20th Century American Costume Jewelry” also documents the ups and downs of the U.S. jewelry industry throughout the century, as the Great Depression affected demand and two World Wars affected supply.

Napier wasn’t known for just one style or genre like Trifari’s rhinestones or Monet’s metalwork. Starting as E.A. Bliss, the company produced ornate belt buckles, hair pieces, matchsafes, and chatelaines. Over 125 years, the firm that became known as The Napier Co. in 1922 made thousands of necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and brooches, too: Everything from frilly sterling silver filigree and modernist gold-plated metalwork to jewelry with beads, crystals, Catalin, and charms.

An E.A. Bliss silver mesh chatelaine purse, circa 1907 to 1915 features an Art Nouveau motif with flowers and a nymph. (From “The Napier Co.”)

“It was one of the first companies to bring jewelry designs directly from Paris,” Lewis says. “Americans have always loved Parisian fashion. Even before the turn of the century, company designers would go to Paris to look for unique findings and stones and to meet with people who make stampings. Then they would introduce something similar to the American market.”

“We always maintain that Napier was not a costume jewelry manufacturer.”

During its Golden Age in the 1950s, Napier put out everything from a subdued line of “tailored” jewelry to countless numbers of bombastic pieces that might be modernist abstractions, mid-century kitsch, or explosions of Rococo frippery.

“Much of Napier’s jewelry was considered avant-garde at the time,” Lewis says. “All of its designers were artists first. And they had complete freedom to design what they wanted before they presented it to the team. The designers weren’t instructed to create within a particular genre, and that’s why Napier had so many different looks. Napier’s process was more organic, stemming from the individual jewelry designer.”

An early 1950s Napier demi-parure with necklace, earrings, and bracelet (not shown) features fluted gold-plated brass lined with faux pearls. (From “The Napier Co.”)

Today, such statement pieces might seem a bit garish, but no more so than anything you’d see on the runway. In fact, on her book’s Facebook page, Lewis regularly features a modern-day piece of jewelry worn by a fashion icon like Rachel Zoe, and its vintage Napier counterpart. “When I look at what designers are doing today, I can go into my own collection or my own archive of photographs, and I can always find something that looks just like their piece in Napier designs from the ’50s, ’60s, or ’70s.”

In her book, Lewis explains that James H. Napier, president from 1920 to 1960, refused to use the term “costume jewelry” to describe his products, and he insisted rhinestones were to be called “foil-backed faceted crystal stones.” In no way did Napier, who would travel to Europe with fellow jeweler William Hobé, want his products to be associated with anything cheap or low-quality. He wanted consumers to take note of the attention to detail and the top-notch materials that went into the pieces, including real gold and sterling silver, Swarovski crystals, and Japanese nacre faux pearls.

A 1950s Napier bracelet with “foil-backed faceted crystal stones” in shades of sapphire. (From “The Napier Co.”)

“We always maintain that Napier was not a costume jewelry manufacturer,” says Meoni, who was the president of Napier between 1985 and 1995. “Napier was a fashion jewelry manufacturer because we were making a high-quality product on the high-end of the market. We catered to the upper-level department stores such as Bergdorf Goodman and Gump’s. The two major brands of costume jewelry, Trifari and Monet—in the years that I knew them in the ’50s and the ’60s—were rarely referred to as fashion jewelry producers.”

And the quality of Napier was one of the reasons that Lewis became so obsessed—enough to make several trips to Meriden, Connecticut, where The Napier Co. plant had been located.

“I spent my honeymoon having lunch in Meriden with retired Napier employees,” Lewis says. “My husband and I would sit with them around the table, and I’d put on the recorder and ask questions as they shared stories and reminisced. I ended up with all this rich history, from the CEO and the designers, down to the plant manager and regular employees. One designer I interviewed started in 1941, and most of them had stayed with Napier for 30 to 50 years. It was great to have the opportunity to speak with them while they’re still alive, because they’re all in their 70s and 80s.”

These two pairs of clipback earrings were designed with Asian-inspired themes. (From “The Napier Co.”)

These retirees spoke to Lewis with fondness about the head honcho, James Napier, who took over the E.A. Bliss Company in 1920 and quickly renamed it after himself. But Napier wasn’t exactly a soft, cuddly boss. He demanded excellence and productivity from his workers while he wheeled and dealed in New York City as an influential fashion-industry executive.

“Napier made jewelry that fits any kind of mood that you could want to convey in your outfit.”

“Mr. Napier was really particular about putting out an absolutely great product,” Lewis says. “The name ‘Napier’ even means ‘without equal.’ He held all of his employees to a very high standard. And the employees were very protective of Mr. Napier, as well as the company and its integrity. People loved and feared Mr. Napier at the same time. He was very strict with them, and he ran a tight ship.”

Meoni, who started at The Napier Co. in 1959, remembers the employees bending over backward to keep their boss happy. “Jim Napier pretty much ran the company from the Fifth Avenue office in New York through the telephone,” he says. “He would come to Meriden, where the factory was, in the summer for a month or two, and like many successful entrepreneurs, he had some idiosyncrasies. He had a plant in his Connecticut office that was important to him—somebody had given it to him as a recognition. When he was away, the plant was kept at a greenhouse to keep it alive and well. When we knew he was coming back, someone would have to retrieve the plant from the nursery, and put it in its place in his office.

This modernist 1950s demi-parure features “hammered” silver-plated brass and faux carnelian glass stones. (From “The Napier Co.”)

“Napier’s chauffeur, Tommy, lived in Meriden,” Meoni continues. “When the old man wanted to go to the racetrack where he had box seats, Tommy would have to drive the limousine to New York City, pick the boss up, and take him to the track. That limousine was the only car that was allowed to park on Fifth Avenue and not get a ticket because the old man, whenever he saw one of the local policeman on the beat, he would slip the guy $50 as a token of his appreciation.”

Jim Napier was such a competitive sort that he may have even signed off on rewriting company history. In her book, Lewis unravels a mystery about Napier Co. that haunted her throughout her research. Most online resources state that the firm started out as the Whitney and Rice Company in 1875 before it became the E.A. Bliss Company in the 1880s. But when Lewis took a look at 1870s business directories and incorporation documents, she couldn’t find one that suggested anyone named Whitney or Rice was involved when Egerton Ames Bliss launched his silver novelties company in 1878.

A Napier 50th anniversary announcement from 1928 celebrates a start date of 1878. Later anniversaries celebrated a 1875 start date. (From “The Napier Co.”)

In fact, her research reveals that all the company’s internal and publicity material, up until the end of the 1920s, lists the start date as 1878. However, Lewis found one internal document from 1929 where “1878” was crossed out, and “1875” was written to the side, in pencil. From the 1930s on, Napier’s start date was always publicized as 1875, even for inner-company anniversary celebrations.

“The reason that I think that they did that—and I can’t say for certain—was that Whiting & Davis was founded in 1876,” Lewis says. “Since Whiting & Davis was always a major competitor, especially with mesh purses and chatelaines, to be able to say that Napier is the oldest fashion jewelry manufacturer in the United States would serve the company well.”

The discovery of King Tut’s tomb inspired the Egyptian Revival style, which Napier adapted with this rare 1920s brass hinged cuff bracelet with a green glass cabochon and double snake motif. (From “The Napier Co.,” courtesy of Leslie Burke)

But it’s likely that Napier Co.’s endless output of creative designs appealed to consumers the most—particularly in the 1950s, when the costume or fashion jewelry market exploded. To that end, the credit goes to Frederick W. Rettenmeyer, the head designer at Napier from 1907 to 1964, whom Meoni calls, “the design genius at the company.” Rettenmeyer took several trips to Europe to study the latest fine-jewelry designers coming from top houses like Cartier. But he also found inspiration relaxing at his Connecticut lake house and on the coast of Maine, where he painted landscapes.

At work, Rettenmeyer had the space and materials to let his imagination run wild—which is how he came with some of Napier’s most popular pieces such as the company’s first 1950s charm bracelet.

“One of the things a jewelry company does, particularly Napier, is accumulate thousands of pieces like stampings, beads, and stones,” Meoni says. “Because Mr. Rettenmeyer was such a frugal guy, none of that stuff ever got thrown away. If we had to buy 10 gross of beads, which would be 1,200 to 1,400 beads, and we only used 200 because it was a limited production, the remaining would go into a box and be put up in the attic storage.

The 1950s Napier “Lanterns” charm bracelet was a popular design. (From “The Napier Co.”)

“Rettenmeyer’s genius was that he would wander through this storage area every once in a while and grab one of these beads, one of these stampings, and one of these findings. He’d take them to his office and monkey with them until he’d created an interesting piece of jewelry.”

During the ’50s and ’60s, Rettenmeyer and his design team, including Eugene Bertolli, came up with more than 100 clever themed charm bracelets including “Lanterns,” which looks like assemblage of various Chinese lanterns; “Tropicana,” which employs the iridescent opaque beads known as “moonglow” in bright fruit colors with leafy findings; and “Buddha,” with metal Chinese characters, antique coins, and Buddha figures.

In the 1950s, Napier introduced over-the-ear “chatelaine earrings.” Designed by Eugene Bertolli, this experiment must not have been a hit, as they’re quite rare now. (From “The Napier Co.,” courtesy of Pamela Wiggins)

“For the most part, they were silly and whimsical conversation pieces,” Lewis says. “You got noticed when you were wearing a charm bracelet. It was bulky and clunky, but not in a bad way. As a collector, it’s an area that I focused on researching, because the charm bracelets are the most faked Napier pieces on the market. They are still so popular.”

Even though the charm bracelets are coveted, they only constitute a fraction of Lewis’s tome, which emphasizes exactly how important and influential Napier was. “The one thing that made the company stand out was that it did everything,” she says. “Napier did beads. It did the rhinestones, what the jewelry industry calls ‘color.’ Or Napier would do metal. Compare that to, say, Monet, which was mostly known for its metals. Trifari was known for its color. Marvella was known for its pearls and its beads. Napier did it all.”

This early 1950s Napier set, made of silver-plated brass circular discs embossed with a “stars and scrolls” motif, is among Napier’s more subdued jewelry. (From “The Napier Co.”)

But is it wearable for the average woman in 2013? “Napier made jewelry that fits any kind of mood that you could be in or want to convey in your outfit,” Lewis says. “You can wear the ‘tailored’ jewelry anywhere. If you want to wear something sparkly for a cocktail party, you can absolutely find the perfect piece of Napier. You can even pull off wearing something funky to a party, because it’s a conversation piece. I get comments every time I wear one of these pieces. When you’re somewhat shy, like I am, it’s a great way to open up a dialogue with another person.”

Could You Make Napier Jewelry Work for You? Scroll Through and See

(To learn more about Melinda Lewis’s book, “The Napier Co.: Defining 20th Century American Costume Jewelry,” and to watch the preview video, visit her site.)

Modern Metallics: Monet Costume Jewelry

Modern Metallics: Monet Costume Jewelry

Hidden Gems: Lost Hollywood Jewelry Trove Uncovered in Burbank Warehouse

Hidden Gems: Lost Hollywood Jewelry Trove Uncovered in Burbank Warehouse Modern Metallics: Monet Costume Jewelry

Modern Metallics: Monet Costume Jewelry Rhinestone Dynasty: Karl Eisenberg Talks About His Family's Costume Jewelry

Rhinestone Dynasty: Karl Eisenberg Talks About His Family's Costume Jewelry Costume BroochesA carefully chosen vintage costume brooch can say a lot about a woman. If s…

Costume BroochesA carefully chosen vintage costume brooch can say a lot about a woman. If s… Napier JewelryThough the history of Napier goes back to the late 19th-century, when the E…

Napier JewelryThough the history of Napier goes back to the late 19th-century, when the E… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

wow , very interesting posting:) love it !!!! stunning jewelry!!!

Have seen it for many years but never knew about Napier. Thanks for filling in the gaps!

I have ordered Melissa’s book and will also be interviewing her for my blog. Napier’s long history of jewelry design deserves the attention! I recently acquired the double dragons Napier necklace for the shop. I love the images you have included here, like the deco snake cuff. Amazing!

Great article! I can highly recommend Melissa’s book. I bought two, one to read and one for an investment. I have at least 35 jewelry books some I have had for over 14 years old, never have I seen a book with as much valuable information. That information is not only about the Napier Company, but the industry as a whole. The way that it is laid out it gives you a great understanding of the different styles of jewelry that was popular at the time.

A great book and an obvious labor of love.

Thank you Lisa for this history into the Napier jewelry world!

A superb article Lisa! Thank you for the much needed insight into a great company and its fantastic jewelry.

Thank you all for the lovely comments about my book. Lisa did a fabulous job with the piece, and was a pleasure to be interviewed by her. The pictures shown are from the book. If you love Napier, and love its history, there are over 4,000 more images to enjoy in the 1000+ page text. Melinda L. Lewis

Wonderful article I will always treasure my Napier pieces

Thank you

Did Napier make any jewelry that had the marking Vietnam?

Did Napier make lots of Christmas Tree pins? I think I found one at Tillie’s Attic in Chandler, AZ.

MY MOTHER WAS A NAPIER AND I AM VERY PROUD OF THE FAMILY NAME, THERE HAVE BEEN MANY DISTINGUISHED NAPIERS AND PROBABLY A LOT MORE LIKE MYSELF WHO NEVER ROSE TO FAME BUT ARE VERY PROUD OF THIS DISTINGUISHED NAME. i WEAR THE FAMILY TARTAN WITH IMMENSE PRIDE

Gosh, I remember all my Glamour and Cosmopolitan magazines in the 70’s had the most exquisite Napier advertisements with catchy lines such as “Napier is Choosier” and a few others. I always admired the jewelry and the way it was presented. Unfortunately, living in Canada, I couldn’t buy any of it.

Lisa – thank you for this wonderful research article into a special giant from America’s history of amazing jewelry designs.

Alink bracelet gold pat number 4774743