Danger! Warning! Intruder Approaching! For recalling the fears and aspirations of the space-race 1950s, Japanese toy robots can’t be beat. But how much do we really know about these tin creations, in hindsight one of Japan’s greatest postwar exports? In this interview, robot collector Justin Pinchot gives the backstory on Japanese tin toy robots and how they reflected the postwar psyche and values of both Japan and the U.S. Pinchot can be reached via toyraygun.com, which is a member of our Hall of Fame.

Everyone is always looking for the next big thing. In the 1960s, it was going into space. In the ’40s and ’50s, the frontier was technology, with a particular focus on “What’s going to make our lives easier?” For the very first time, you had cars with automatic-transmissions, automatic washing machines, and perpetually cooling refrigerators.

I mean, we were coming out of an era when you scrubbed your clothes on a washboard and cooled your icebox with a big block of ice.

Even the first electric wristwatch, introduced around 1957, was a marvelous innovation. Prior to that, you had to wind your watch every day, and if you forgot, your watch wound down and stopped and you didn’t know what time it was.

Robots fit into that drive for convenience. They were going to be the next big thing. Everyone would have a personal robot, like Rosie the robot on “The Jetsons,” who would do your chores for you.

The idea was that if we had things like robots to make life easier, we’d be able to be more productive, make more money, and be more prosperous.

Later, of course, we realized, that we needed robots to build cars and help us get into space. That’s when real robotics came into play.

Collectors Weekly: Why were people in the West fearful of robots?

Pinchot: The worry was always that the robot would gain too much intelligence and decide what it wanted to do on its own. A big theme in early science fiction was that the robots we created would run amok. It’s still pervasive today with computers. Are computers ever going to get to the point where they can have emotions, or where they can make decisions that we didn’t tell them to make?

When I was a kid, I thought Japanese tin toys were kind of cheesy.

That fear surrounds all technology is embodied by toy robots because they’re designed to encourage fantasy. It’s easy to fantasize that a robot’s going to take over, take your money, or somehow direct your life in the wrong direction.

When I was a kid, I feared robots. Toy companies deliberately made them big to amplify that fear factor. It’s the same thrill that makes kids run to horror films. We know the fear factor is not real, but it’s fun to pretend. Part of the allure of robots, for sure, is that they resemble us, but they’re not us. We created them, but there’s always the possibility that something can go horribly wrong.

Collectors Weekly: How were robots viewed in Japan?

Atomic Robot Man might have been designed before World War II, but it was released shortly thereafter.

Pinchot: Well, the real rise in modern-day toy robots stems from the postwar Japanese robots. Japan was rebuilding, with U.S. encouragement. There had been a well-established tin toy business in Japan prior to the war, so it was pretty easy for them to pick back up and continue to produce toys.

The atom bomb had a major impact on the marketing and packaging of postwar Japanese robots. It was the story of a giant, technologically advanced superpower, crushing another superpower. That whole theme got translated into space toys and robots. If you look at some of the early robot boxes, you will see robots stomping through cityscapes, causing destruction as they go—that was a metaphor for what had happened with the bombs.

I can’t speak for how robots were viewed in Japan, but they certainly seemed to latch onto whatever the U.S. market found fascinating. The U.S. perception of robots came before the war, in the 1930s, when Jules Verne novels and Buck Rogers serials were popular. It was the decade of Art Deco and Cubist geometry, which was infiltrating design at that time and also influenced how we imagined robots.

The idea of automatons doing our work for us was big in the ’30s, and the Karel Capek’s play “Rossum’s Universal Robots,” or “R.U.R.,” had put the term “robots” in the public consciousness. By the late ’30s, it had all started to manifest itself.

Collectors Weekly: How did Hiroshima and Nagasaki affect Japan’s take on technology and the products it made?

Pinchot: I think they realized they needed to catch up technology-wise, but really they were just trying to rebuild. They were thinking in terms of survival, but the overall influence on technology is what prompted them to design and build toy robots.

After the war, most toy makers were producing clockwork toys, but the Japanese embraced batteries and motors.

The timing was right. All through the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s you had cowboy heroes, like Tom Mix and Hopalong Cassidy. That era was ending because the Western frontier, with its cowboy-themed shows and toys, had been done to death. Toy makers said, “Well, what’s next? We’re going to into space!”

Japanese tin-toy makers picked up on that immediately. Space and robot toys were indicative of the times, where all of a sudden we lived in a world with atomic bombs and rockets. It was part of a great trend that included the automation of everything from sewing and washing machines, to cars with automatic rather than manual transmissions. It was natural to see the next frontier as a place filled with beings that would do the work of humans, and also help humankind to become more technologically advanced.

Collectors Weekly: Why is it that robots are so connected to space exploration in people’s minds?

Pinchot: A lot of our leading thinkers who were dealing with the prospect of real space travel were trying to figure out how we’d be able to do things remotely. Robots fit very neatly into that for a lot of reasons. For one, they don’t need to breathe.

Many toy robots were sold simply as “Robot,” so collectors have taken to giving them names. This one is known as a “Domed Easel Back.”

Toy makers didn’t always take this into consideration. For example, There are several different incarnations of a toy robot called “Easel-Back Robot.” Its name was really just “Robot” on the box, but people call them “Easel-Back” because he’s got a little wire in the back that helps him stand up so he doesn’t fall over. (Many toy robots were just labeled “Robot,” so collectors make up nicknames for them to differentiate between the myriad models.)

Well, one of the variations of the Easel-Back is what they call the “Domed Easel-Back.” He’s got a clear plastic helmet over his head. It’s comical: Why would he need an oxygen helmet when robots don’t breathe?

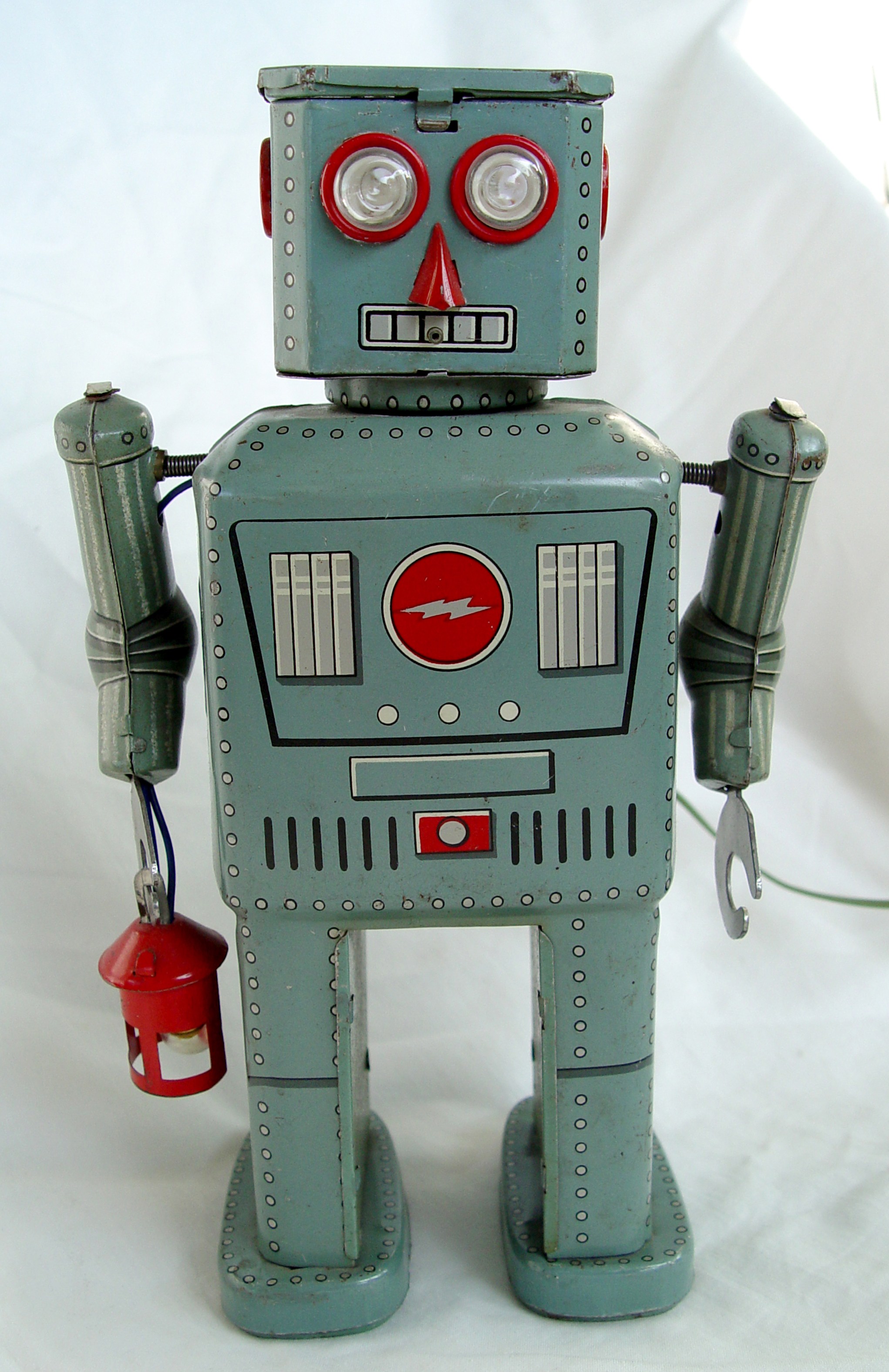

Another, the “Lantern Robot,” not only has lighted eyes, but he’s also carrying a lantern. So again, why does he have a lantern? Why would he need something as primitive as a lantern to light his way? It’s a very odd conundrum, but those types of fantasy incarnations in toys are really fascinating for collectors. It’s really endearing and charming to see a mechanical robot holding a lantern. It’s a funny juxtaposition.

Collectors Weekly: In the ’50s postwar Japanese culture, robots tend to be helpers. Where did that come from?

Pinchot: The whole concept is that no matter how big or overwhelming things get, you can still have power as a small, puny human. In the far reaches of outer space, where there are any number of unimaginable foes with great powers, you now have something to do your bidding, something that is equally as impressive as your enemy but under your control. Whether it’s Rosie the Robot, Tetsujin, or Astro Boy, the concept is always the same.

The basic premise of robots is that they are willing and able to do what we cannot or will not. They allow us to be in two places at once. And they’re physically stronger than we are, so they can do work for us like a machine. There’s a Japanese robot called the “Busy Cart” robot, which is a construction worker robot with a big wheelbarrow. The real fun comes when we cross the line and give them a personality or thinking powers.

Robby, the robot in the 1956 movie “Forbidden Planet,” was the first robot who attempted to think for people. Naturally he made mistakes—when one character wanted gin, Robby made a bunch of bottles of gin for him, not realizing that it was a bad thing to do.

The theme of robots doing our work for us, helping us, and really being an extension of us will never go away. They are always tools for us to get what we want. The fantasy, fun, and fear comes in when we start thinking about robots taking over—that we might one day design them so well by giving them minds of their own that we can’t control them anymore.

That’s why robots, I think, were so popular; there were so many aspects of play to them. They sort of looked like us, but they weren’t us at all. And best of all, we got to control them.

For kids this is especially welcome because they really don’t have much control over their worlds. They have to go to school, they have to eat at a certain time, they’re told to do everything. But if you give a toy to a kid that allows him some modicum of control over his life, guess what? He’s going to love that toy. He’s never going to put that damn thing down. It’s the same reason why kids love bicycles and toy trains. They get to drive.

Collectors Weekly: Toy robots were initially made for export, but did they sell well in Japan?

Pinchot: I think they did. I may be wrong on this, but I believe they were popular because the Japanese liked American values and culture. They were starting to get tuned-in to our culture and, in reflecting that, robots were popular in Japan as well.

The computer killed the idea of the robot because, really, the computer is the robot.

A U.S. company like Marx would design a toy robot, Smoking Spaceman, for instance, which came out in about 1962. Japanese manufacturers produced this toy for Marx, but they liked it so much they made their own version, which they gave a different name, colors, and packaging, but with Japanese text and characters. They took a lot of our designs and produced them for their domestic consumption.

There were not huge numbers of these tin Japanese robots because Japan is a small country compared to the U.S., so the runs of robots for the Japanese market were smaller. Today, those Japanese-issue toys are often more coveted, at least in America.

Collectors Weekly: The first toy robot was Lilliput. When was it made?

Pinchot: I’m thinking it was definitely before the war, as late as 1941 or as early as 1938. There was another one that might have been designed before the war, but released shortly after, called Atomic Robot Man. Both were very, small clockwork windup toys with “pin” feet that make them walk or, more accurately, sort of waddle back and forth.

After the war, the small battery-operated motor was devised, and the Japanese were the first to put them in toys. Most toy makers in other countries were still producing clockwork toys, but the Japanese embraced batteries and small motors. They were the only game in town as far as that was concerned. They innovated that type of toy, and it became very popular. From the early 1950s all the way to the late ’60s, they dominated the market because of this innovation, and because the toys were very inexpensive.

In many ways, the Japanese toys of the 1950s were updates of automatons from the 1920s, which were windup toys. They could walk, but they were also very detailed. Take a mechanical fortune teller, for instance—her eyes would open and close, her head would nod, and her hands would move. The problem was these toys were horrendously expensive.

The Japanese were able to affect that same motion much more cheaply with battery-operated motors. So they were producing something that previously had been very expensive but all of a sudden was very affordable. They were great toys.

By the ’70s, though, plastic was really coming in big time, and China also entered the picture. Chinese toy production eventually toppled Japan as the number-one toy producer.

Collectors Weekly: What sort of things did Japanese tin robots do?

Pinchot: They could walk and you controlled them with a remote control battery box connected to the toy by a wire. If it was a clockwork toy, you would wind it up, turn on its switch, and it would walk. With battery-op robots, they not only walked forward but backward as well, and in some cases they had a whole host of other functions; maybe a spinning wheel in its head, or ears that moved, or lighted eyes—add lights to anything and kids go crazy.

It was a bit of technology that kids could actually play with and relate to. Prior to that, technology was exclusive to adults with their new fangled washing machines, cars, and freezers. Actually, the very first wireless remote-control toy was a Japanese robot called Radicon Robot. So here you had a pretty big advancement in technology, and it was for a kids’ toy. That’s amazing.

Collectors Weekly: In America, Ideal came out with Robert the Robot in 1954. Was that also a remote-control robot?

Pinchot: Yes, but it was simple and was operated by a hand crank. The toy took batteries, but only to make the eyes light up; the walking and talking action were generated by a hand-cranked wired remote. A lot of different Japanese robots came out after Robert and they improved upon the idea a hundred fold. For example, Masudaya had the Gang of Five, which were large, tin lithographed, skirted robots just like Robert, except they were all tin and fully battery-operated.

Robert was cool, but he was somewhat crude compared to what you had in the Japanese robots. They were much more advanced and much more interesting for kids. If you asked a kid to choose between a plastic Robert the Robot and a tin, lithographed, brightly colored, eyes-lighting, noise-making, bump-and-go action Japanese robot, the Japanese tin robot wins every time.

Collectors Weekly: So when American companies manufactured their own toys they made them out of plastic, but the tin robots they sold as their own products were actually made in Japan?

Pinchot: Yes, that’s exactly right. For instance, Macy’s sold several different varieties of toys, some made of plastic by U.S. manufacturers and others made of tin from Japan. The tin Japanese-made toys were much more popular. But the Americans realized early on that they couldn’t compete with the tin and the batteries. We would produce something in plastic, and you would see it a year or two later in tin lithograph and battery-operated.

This robot carries a lantern, for which he’s named, even though a robot would not need such a primitive light source to see.

Obviously we had access to tin, but the process and labor were too expensive. We simply couldn’t produce battery-operated tin robots for the same price that they could. What the Japanese could retail for $6 here—a really big, impressive robot—would have cost $15-$20 for us to produce. It was easier for U.S. companies to buy from Japan, mark them up, and sell at a profit.

So you had companies like Marx and Cragstan, which was an American company that sold only Japanese stuff, commissioning the Japanese to manufacture U.S. designs. They’d send plans to Japan, have the product made there, and then ship it back. And as we were talking about earlier, sometimes the Japanese went, “Wow, we like that design,” and then they’d produce it for themselves under a different name with Japanese packaging.

What’s funny is that when I was a kid in the late ’60s and early ’70s, nobody wanted the Japanese tin toys anymore. They didn’t like them at all. I thought they were kind of cheesy. I was like, “They break easily. They rust. They’re easy to stomp on.” Even when I started collecting toys, I didn’t want tin litho. I thought it was junk. I wanted Art Deco pressed-steel toys that were American made.

Then, suddenly, there was this big sea change for me, a big paradigm shift. I was like, “Wow, I’ve got to have that.” It wasn’t a cheap toy to me anymore. I got the design, I got the whole impact of it. I understood the value of the design, the rarity, the uniqueness. But I had to evolve into that as a collector. Today, cast-iron and pressed-steel toys are nowhere near as valuable and collectible as battery tin litho toys; a complete reversal from the 1970s and ’80s.

Collectors Weekly: When did you get into collecting tin-lithographed toy robots?

Pinchot: Around 1991, when I was 28 and selling antiques at the Rose Bowl Flea Market, someone brought over a robot to show me. I just lost my mind. It was so cute and so unusual. I had never seen anything like it. I didn’t even know they existed. I put the word out that I was looking for robots and started collecting voraciously.

If you give a kid a toy that allows him some control over his life, he’s never going to put the thing down.

My family’s always been into collecting. I had Hot Wheels from when I was a kid, so I started collecting those. I have vintage Art Deco microphones and Catalin radios and balloon-tire bicycles. I’ve collected so many things, but robots really took over. I was just nutty for them. I don’t know what clicked in me that made me crazy for them; maybe that they were automatons and were so cute.

It was pretty neat, the reaction that people had to them without really having any notion of what they were. Everybody just seems to respond to them for some reason. They’re so fun and unusual, and they’re so representative of an era. There have been incarnations of robots over and over again, in movies with R2-D2 from “Star Wars,” and so on.

Collectors Weekly: What is the typical reaction of non-collectors when they first see them?

Pinchot: Usually it’s just wonder. People say, “What is this?” Now that there’s sort of a general understanding of them, it’s not quite the same because people have seen them in commercials and elsewhere recently. But initially, back in the ’90s and early 2000s, most people really didn’t quite know what they were. They would want to play with them and see them work.

The X-70 robot is also known as “Tulip Head” because his head (left) would open up like a flower (right).

I have a battery-operated robot called X-70, but the collector name is “Tulip Head” because he’s got a big bullet-shaped head. He walks and then he stops, and his head opens like flower petals to reveal a rotating camera inside. Then it closes again, and he starts to walk. It’s fascinating to watch. I turn that robot on and people just lose their minds. Even if they don’t know anything about toys or robots, they’re fascinated. They can’t help but watch it because it’s so charming.

Every girl that I showed the robots to loved them. When they would come over and see all the items in my house, that’s the one thing they would gravitate toward. On my first date with my fiancée, she came over earlier than I expected. I still had to take a shower. I had a bunch of robots and a little neon clock on my desk. When I came out of the shower, she had positioned all the robots as if they were praying to the neon clock.

That’s when I fell in love with her. I was like, “Okay. That’s my kind of girl.” She didn’t really know anything about robots, but there she was, playing with them, enjoying them, and asking me all sorts of questions. She got them right away.

Collectors Weekly: You actually play with your robots?

Pinchot: Absolutely! I love to demonstrate them for my friends and visitors. My general attitude about collectibles and antiques is that if I can’t play with it or use it, then I don’t really want to have it. If I have to put it in a case or lock it away or not get enjoyment out of it, I don’t want it. I put batteries in them every couple of months and run them and play with them.

I take care of them, I keep them clean. I don’t let fingerprints build up on them because the acid in finger oils will etch them. So I don’t let them get degraded, but at the same time I definitely play with and enjoy them. That’s what they’re for.

If I have friends come over with their kid, I won’t necessarily let the kid play with a valuable vintage toy robot, but I’ll play with it with him, and show him how it works.

I used to keep a stock of reproduction robots that were cheap that I could give to child visitors. If a friend came over with his son, we’d play with the robots for a while, then I could hand him one to take home. It’s sometimes hard to relate to a 5-year-old, but if you’re playing with robots, all of a sudden you’re both in the same world.

Collectors Weekly: Are vintage toy robots a hot commodity now?

Pinchot: They have been since 1996, when a guy named Matt Wyse auctioned off his collection of robots at Sotheby’s. It was the first time any major auction house had really handled toys robots. Sotheby’s is a very prestigious auction house. When they decided to handle tin-litho toys in 1996, it gave those toys a huge amount of credibility. They became very hot very quickly after that. Luckily, I had already bought quite a few of them, so I was kind of ahead of the curve. I was able to build a reasonably good collection before they got too expensive.

In the last two years, we’ve had several major collections get dumped on the markets via auction, and so the market is quite saturated right now. It’s a great time to buy if you’re just starting to collect because there are a lot of them on the market—the prices are down because of the economy and the glut of availability. They’re in a low cycle, but I have a feeling they’re going to be popping again in the next couple of years.

Collectors Weekly: One of these robots went for $42,000, right?

Pinchot: Yes, Machine Man, a variation of the one of the Gang of Five robots, which are each about 18 inches tall. They’re huge, skirted (as opposed to separated legs) tin-lithographed robots. One has a target on its chest, and when you shoot a dart at it, it turns and moves away. Another only has bump-and-go action and a lighted face. One of them makes a train noise, and then there is the aforementioned Radicon Robot, which was not the first in that series but was one of the earliest wireless remote-controlled toys.

Vintage toy robots remind us of a simpler time when things weren’t quite so advanced and scary.

That group of robots was at the top of the collecting game for the longest time. When Machine Man showed up at Sotheby’s in 1996, it was a variation no one really knew existed. The Gang were the “Gang of Four” prior to this time, then all of a sudden there was a fifth member added. Since then, others have turned up that have sold for even more money.

Now people are realizing that the Gang of Five robots are not as rare as originally thought—several more have turned up. In regards to the value and the collectability of Machine Man, while it’s still a very hot robot, it’s not as hot as some of the even rarer toy robots that have turned up since that people never knew existed. But the Machine Man auction really got people’s attention. It prompted people start looking for robots and pulling them out of their attics.

Collectors Weekly: What do you think of the reproduction robots made since the mid-’90s?

Pinchot: Reproductions both hurt and help the market at the same time. They help because they get people interested in the original toys, but they hurt because people who would have spent real money to buy an original, perhaps $1,000, will now buy a very close reproduction for $20, so those buyers are now out of the market.

But whenever a reproduction raises the social consciousness of a genre as a whole, it’s a good thing. Suddenly the originals become more valuable and are preserved. A lot of my friends are collectors, and we all know that we can’t take this stuff with us; we understand that we are all just caretakers, preserving these things for future generations. So, to the extent that the reproductions encourage preservation of the originals, that’s a good thing. They’ll be coveted for a long time.

Collectors Weekly: Is there a way to distinguish the repros from the originals?

Pinchot: Yes, but it takes a bit of doing. You have to kind of know them to begin with. If you’re just looking at them fresh, it can be very difficult to tell the difference. In fact, even some seasoned collectors will go on the chat boards and say, “Is this original or is this a reproduction?” You’ll get shifty people who will rub off a maker’s mark to make a repro look like it’s an original instead of a reproduction. It can be tough.

This generically named robot is based on Robby, the helpful robot in the 1956 movie “Forbidden Planet.”

The best advice I can give new collector is to get involved, either by going to shows to meet knowledgeable dealers or by reading books and auction catalogs. The more educated you are, the better armed you’ll be. Eventually, you’ll be able to spot the differences very easily.

For example, someone may reproduce a Lilliput robot. It will be very close to the original, but when you stand them side by side, there are obvious differences: The eyes on the repro are embossed rather than concave; the body is a little bit too narrow; the arms are attached a little bit differently. If you don’t have them side-by-side, it can be dificult to tell the difference.

I highly recommend that anyone who wants to start collecting get as many reference books and old auction catalogs as they can before they buying their first piece. They should talk to as many other collectors who are into the hobby as they can.

Most of the people who I got started on robots and space toys did a lot of conferencing before they ever bought their first piece. I did a lot of educating as a dealer—that’s your job. It’s important to educate your buying public so that they know what they’re looking at. The goal is to help them make smart decisions and be happy. It’s all about research, research, research.

Collectors Weekly: Have computers supplanted Rosie the Robot?

Pinchot: The computer, I think, has killed off a lot of things. When I was a kid, I had to go to the library to get information. Now, at 2:00 am, if I need information, I just go online. It’s all there. That’s a good thing and a bad thing. But yes, the computer has killed the idea of the robot because, really, the computer is the robot, and just like a toy robot, we are controlling it. It’s not fantasy anymore. It really is a robot.

This is what killed rockets and space toys. Once we actually went into space, the fantasy aspect was gone—toys started to reflect reality. You had Apollo, Gemini, and all these rockets that had gone into space. Fantasy was pushed aside, but fantasy is a big issue for kids. If you allow them to fantasize, they’re going to have a great time. That’s the definition of play.

But I think the pendulum will swing the other way again, eventually. You’ll get computerized robots. Suddenly, once again, you’ll have kids who can be in control of a robot toy.

Collectors Weekly: So with all this technology at our fingertips, why do people still place a value on robot toys?

Pinchot: Things are so fast forward now. I was in the car the other night with a buddy. My GPS wasn’t working. He said, “Well, let me get on my phone.” I said, “What? You have GPS on your phone?” Obviously, I’m kind of a techno dud, behind the times. It took me forever to get a cell phone. Same with the computer; I didn’t get one until ’98.

One of the reasons why collectibles are so hot is a reaction to future shock. It scares me. It gets me a little apprehensive thinking that technology has run away from us, and, as a result, we get terrible things like the oil spill in the Gulf. These sorts of events are the byproducts and downsides of modern technology. What vintage toy robots and space toys do is remind us there was a much simpler time when things weren’t quite so advanced and quite so scary.

Look at the progress of the last hundred years: Up until then, for the 2,000 years preceding them, things were pretty much the same. In the last hundred years, though, we got electric wristwatches and clocks, fossil fuel and cars, rockets going into space. All of these things came about in the last hundred years. That’s a lot of progress in a very short period of time.

Now people are talking about cryogenics—freezing people and bringing them back to life once there’s a cure for their disease—and about irradiating and “engineering” food. Those things scare me, but they’re also interesting, pushing things forward.

Any kind of vintage collectible reminds us of a simpler time, when things were a little bit easier to digest. Now things are so complicated and so far advanced that it’s a little bit unnerving. Just when you start to get a handle on computers, there’s a Kindle or an iPad. I can barely keep up on technology; it’s fast-forward all the time. But when I look at a vintage toy robot, I think, “it’s so simple,” and it calms me down.

(All photographs courtesy Justin Pinchot)

Cowboys vs. Spacemen: How the Toy Chest Was Won

Cowboys vs. Spacemen: How the Toy Chest Was Won

Vintage Toy Robots: How To Spot The Real Lilliputs From the Repros

Vintage Toy Robots: How To Spot The Real Lilliputs From the Repros Cowboys vs. Spacemen: How the Toy Chest Was Won

Cowboys vs. Spacemen: How the Toy Chest Was Won From Boy Geniuses to Mad Scientists: How Americans Got So Weird About Science

From Boy Geniuses to Mad Scientists: How Americans Got So Weird About Science RobotsThe 1950s was a particularly good decade to be a toy robot. The world was g…

RobotsThe 1950s was a particularly good decade to be a toy robot. The world was g… Revell ToysThough many collectors associate the Revell brand with model kits for cars,…

Revell ToysThough many collectors associate the Revell brand with model kits for cars,… ToysToys are vehicles for the imagination, the physical objects children manipu…

ToysToys are vehicles for the imagination, the physical objects children manipu… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great interview Justin! Thanks for giving me a little stress relief today. It’s fun getting lost in another world for a little while.

You know, Americans have historically loved robots as well. In Isaac Asimov’s “I Robot”, the robots take over but are generally the good guys. America’s two premier sci-fi screen franchises, Star Wars and Star Trek, both feature good robots (R2D2, C3PO, Data) rather than evil ones (cyborgs and corrupt humans are the villains in both). And Japanese shows featuring virtuous robots, like Voltron and Gigantor (i.e. GoLion and Tetsujin 28) have gained a wide following in America.

Tea serving robots were popular in Japan about 150 years ago!

I just picked up a 1954 YOSHIYA Sparky Robot woth orignal box. How can I tell if the box is indeed original or a repro?

Justin, I was at the Matt Wyse Sotheby’s auction, in NYC, 1996, my bother and I had several of Matt’s robots purchased at a earlier date we wanted to see what the prices people were spending at that time. You can tell if you buy a robot in the last 10 or so years, take a look at their box, repro’s say made in China, or list as, haha toys or have a ‘ME XXX’ number on it , which means made in China. There are many robots made today in Japan that are collectible,but as a limited eddition, as well as others made for the ‘Forbidden Planet Movie’ of 1964. Justin I could write a book on collecting all robots made in Japan, Germany, China or any other country. If anyone out there want s to talk to me about robots, please email me. Justin, I don’t totally agree with all that you said in the first part of your talk, but on the whole it is good info for the novice. Oh! yes just because a robot is made in China, it doesn’t mean it is not collectible….there are some that are almost with the same quality as Japanese robots. It depends on the type and actions they have. Kidtwist

The Maschinenmensch (machine-person) – a robot built by Rotwang to resurrect his lost love Hel in the 1927 film Metropolis, must have influenced the zeitgeist of many nations in the post-war era. A film created in pre-war Germany with a female robotic character and a story with communist undertones, must have fueled fears of a dystopian technocratic future.

Undoubtedly, the proliferation of Cold War sentiments was underwritten by such a premise. And toys of the age prepared young minds to adopt the social imaginary (as surely as baby dolls prepared women to accept their role of domestic servitude and birth babies for the new economy).

Unfortunately, Metropolis suffered because of its place in history, yet it’s still beautiful and thought provoking … and still remarkably relevant.

I have a tin robot Exactly like Flashy Jim EXCEPT it is not remotely wired, it’s color is silver and it is a Wind Up toy. No batteries needed.

It’s a bit rough and missing the antenna on its head. The only mark is inside the left leg, it says JAPAN. Is this earlier than Flashy Jim?