In her 2016 book, “Innocent Experiments: Childhood and the Culture of Popular Science in the United States,” published by the University of North Carolina Press, historian Rebecca Onion explores American ambivalence toward science education over the last two centuries. As she delved into her research, Onion observed that even during the times that adult scientists have been eyed with suspicion, Americans have always loved the idea of the child scientist—specifically little white boys—exploring and experimenting with untainted hearts. Once the boys grow up, however, their love of science is viewed as eccentric, dorky, and possibly a bit unsavory.

The cover of Innocent Experiments: Childhood and the Culture of Popular Science in the United States, by historian Rebecca Onion.

That’s how we end up with a public that, on one hand, gets excited about topics touched on grade school—like news about Saturn’s rings or robot cars—and, on the other, fails to support important long-term research about climate or disease. When it comes to science, it’s as if Americans revert to their collective childhoods, rejecting research data that either conflicts with their worldviews—the theory of evolution, the safety of vaccines—or just doesn’t seem, well, fun.

While researching her American Studies master’s thesis, Onion noticed that at the turn of the 20th century, children were portrayed as having a particular affinity for animals and the natural world in general, whether they’re catching fireflies, climbing trees, or digging in the dirt. At other times—say, 2017—children are thought to intuitively understand very unnatural modern technology like smartphones and laptops.

“At different times in our history, people were invested in the ideas of children as being modern or as being anti-modern, which is a weird paradox I find fascinating,” Onion says. “And then it came to me: Science is the link that connects man-made technology and the primitive natural world.” After all, scientists have to use microscopes to view and fully understand organic cells and microbes.

Top: A mid-century children’s birthday card depicts a cuddly kid space cadet. Above: In Mark Twain’s 1885 novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the titular 13-year-old boy feels most at-ease in nature, rather than in “civilized” 19th-century society. (Images via eBay)

After digging into the subject, Onion concluded that Americans tend to see children as utopian figures who can tap into a pure, unfettered spirit of science, empowered to experiment and comprehend the world around them. But it’s short-lived. Inevitably, a child will lose his or her innocence, and in pop culture, that also means his scientific purity.

“At the time, the instruction manuals for kids’ chemistry sets described the American chemical industry as a patriotic venture and investing yourself in it as a patriotic act.”

“It’s as if adolescents are tainted because they become interested in sex,” Onion says. In this crude but insidious way, the culture discourages untold numbers of adolescents from growing up to be scientists. “If you follow that belief to its logical conclusion, it suggests that every human could be a scientist, or at least good friends with science, if we allowed them to develop that way.”

You can see this phenomenon when the media goes wild for any child who makes a significant scientific breakthrough. Onion thinks the pressure on kids to hit on a groundbreaking discovery is not only unrealistic but also contrary to how most advances in science happen.

“We tend to see science as this mystical beast living in the sky that, somehow, children see more clearly because they haven’t been clouded,” Onion says. “But that doesn’t envision science as a social project. It diminishes the fact that a lot of major scientific discoveries have happened through great effort and many people working together over months and years. Instead, science is conceived of as something that can just descend without having much funding or requiring much organization, administration, or bureaucracy.”

W.E. Wise’s Young Edison: The True Story of Thomas Edison’s Boyhood was first published in 1933. (Via eBay)

When Americans do get excited about scientific discoveries made by adults, it’s still through an immature, fun-centric lens: The vast social project of science is ignored in favor of celebrity scientists mythologized as stubborn individuals—similar to cowboys on the frontier—who strike out on their own and discover unexplored territory. We see Thomas Edison as a relentless, pioneering entrepreneur and Albert Einstein as an out-of-the-box thinker. Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Bill Gates were the swaggering “pirates of Silicon Valley” who created personal computing as we know it in their garages.

When Onion was digging into historical archives, she unearthed quotes from scientists de-glamorizing their work. “They were saying, in a way, that as a scientist, you don’t get a ‘Boo-yah!’ every day,” she says. “You break a lot of tubes, and you have to wash a lot of beakers, and sometimes things go wrong. In my experience as a historian, it’s the same thing. There are definitely days where you go to the archive and read old magazines but nothing points you toward a conclusion.”

In 2006’s “Astronaut Farmer,” Billy Bob Thornton plays a rancher who makes his astronaut dreams come true by building a rocket in his barn and launching himself into space.

Even in the 21st century, Americans indulge the fantasy of the rugged male scientist who makes some retro-futuristic gizmo straight out of 1950s sci-fi and becomes front-page news. In the 2006 fictional film, “Astronaut Farmer,” a thwarted wannabe astronaut, played by Billy Bob Thornton, risks his family’s physical safety and financial well-being to launch his own manned space rocket from their Texas ranch. In 2009, amateur Colorado scientist Richard Heene claimed his 6-year-old son took off flying in a UFO-like helium balloon he invented (while the balloon was aloft, the kid was safely hiding in their family home). Recently, California inventor Paul Moller has re-emerged, claiming his cherry-red flying car is just a few years away from hitting the market, something he’s been saying since the ’60s.

“A male scientist will recollect blowing things up in their basement lab, horrifying his mother.”

“Often, Americans think ‘Why are we spending all this money on technology and training for scientists when they could just be doing it in their backyards or in their garages?'” Onion says. “That belief is counter to the way that science actually seems to work. We imagine scientists operating like Tony Stark in ‘Iron Man’—which is similar to the myth that gets you Trump. It’s the idea that if we just have one person figure out what to do and cut through the bullshit and impose their will, then everything will be fine. Some guy in a barn—or some guy in a golden penthouse suite—is going to save us.”

The ideal of the boy scientist who grows up to be a scientific hero dates to the 19th century. Upper-middle-class white Victorians started to view childhood as a sacred time instead of seeing their kids as little adults who were put to work as soon as they could walk. Wealthier adults became smitten with images of cute white kids and chubby-cheeked cherubs. Black children, meanwhile, were depicted in ads and pop culture as wild, innately criminal, and precociously sexual. In Pricing the Priceless Child, sociologist Viviana Zelizer details the emergence of modern childhood from the late 1800s to the 1930s, a time when white parents started to define their children as economically “useless” and emotionally “priceless.” “That’s when Western culture started to develop child psychology and theories of child’s play being a child’s work,” Onion says.

The original Brooklyn Children’s Museum, pictured in 1908, was located in a former mansion. (Via WikiCommons)

Studying natural history had been a popular hobby since the mid-19th century for both men and women, who collected seaweed, bugs, animal bones, and rocks to show off in scrapbooks and curiosity cabinets. When pinning butterflies or purchasing taxidermy for decoration or entertainment was deemed cruel at the turn of the century, specimen-collecting fell out of fashion with adults. But these collections could be redeemed if they were employed to educate children.

In 1899, the first museum specifically for children, the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, opened. Its departments included botany, zoology, geology, meteorology, geography, and history, with an explicit focus on “natural study,” which encouraged children to make their own observations and play at doing scientific work of organizing minerals and catching bugs instead of just relying on books.

“In their promotional material, they used the metaphor of the hive—with the children as bees flying all over, doing these busy things,” Onion says. Society would be repaid when these bees metamorphosed into enlightened young citizens and scientists. “At professional presentations, museum curator Anna Gallup would point to one museum ‘alum’ who is now an entomologist and another who went off to Brazil and became an engineer to prove that childhood joy in science produces a benefit to society. The Brooklyn Children’s Museum encapsulated all the promise and also the contradictions of using childhood curiosity to further America’s scientific progress.”

George Ris identifies minerals in his collection at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, as seen in the November 1917 issue of “Children’s Museum News.” (From Innocent Experiments)

After World War I, professional scientists gained esteem in the eyes of the American public. They were usually white men, because of the social barriers preventing women and minorities from becoming lead researchers. The new enthusiasm for laboratory work was thanks to major leaps forward in medicine, whose life-saving research was having a direct impact on American lives. Americans snapped up books about heroic men doing medical research, including Sinclair Lewis’ 1925 novel Arrowsmith and Paul de Kruif’s 1926 nonfiction book The Microbe Hunters. “On a daily basis, people started seeing that science worked,” Onion says. “Suddenly, it was possible to fix diphtheria, which previously killed children quite regularly, and that was exciting.”

Of course, at the same time, Americans were spooked by the use of chemical weapons during the war (see the depiction of Doctor Poison in 2017’s “Wonder Woman”). But, Onion explains, the American chemical industry had become more powerful than ever, as the United States stopped importing chemicals from German companies in the 1910s. The newly thriving industry went on a PR blitz in the 1920s and 1930s to restore Americans’ trust in its chemists.

This 1950s Chemcraft Chemistry Set, #414 Atomic Energy, originally contained uranium. At the time, the United States was in a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union, and professional scientists were just starting to understand atomic energy. Click on the image to see it larger. (Via eBay)

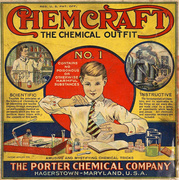

Another crafty way the titans of industry eased the public’s fear of chemical science was to promote home chemistry sets for boys. The two most popular brands produced were by A.C. Gilbert’s toy company, which also made Erector Sets, and by Porter Chemical Company, under the brand Chemcraft. “At the time, the instruction manuals for kids’ chemistry sets described the American chemical industry as a patriotic venture and investing yourself in it as a patriotic act,” Onion says.

White boys were always featured on the boxes, and some of the instruction booklets made the racism explicit, Onion discovered: A 1937 Chemcraft set came with instructions for putting on a “chemical magic show,” which suggested the assistant wear blackface to portray an “Ethiopian slave.” Other sets alluded to American imperialism in more subtle ways.

“A.C. Gilbert had grown up with male role models like Teddy Roosevelt, the sort of guy who went to Africa to have adventures and shoot lions,” Onion says. “In the introductions to the chemistry sets his company produced, Gilbert would write that as a kid, he found heroes in military and adventure tales, but today’s boy will instead be adventuring through the microscope. Practicing science was the new way to be on a frontier. He uses the language of conquering and subjugation, like, ‘We will make the forces of nature bend to our will.’ Chemistry and biology were talked about in the same way that turn-of-the-century pro-empire literature talked about Africa or South America.”

A.C. Gilbert—also known for Erector Sets, American Flyer model trains, and the Gilbert Hall of Science—liked to emphasize his science kits were meant for boys. (Via eBay)

When you look back at the dangerous chemicals Gilbert and Porter included in their science kits—potassium nitrate, sulfuric acid, sodium ferrocyanide, calcium hypochlorite—one might assume that boy scientists in the 1920s and ’30s operated under stricter parental supervision. But Onion says this was not usually the case. A good parent might read the warning in the instruction manual, tell their son to exercise caution, and then turn over the basement, garage, or a spare room to his chemical tinkering—from making batteries to bending glass with an alcohol lamp.

In the 1930s, a public-safety campaign alerted mothers to the dangers of household chemicals, Onion says, which gave them pause about the acids, dyes, explosives, and substances that could create toxic gases in the science sets. Some mothers, unfortunately, learned about those chemicals when their sons had deadly or disfiguring accidents. When the toy industry became more regulated in the 1970s, those substances were removed from chemistry sets.

“Boys taking risks is a recurrent theme in my book,” she says. “It pops up throughout history when advocates of science education, especially for boys, are making the case that boys should be allowed to do something dangerous or daring. A male scientist will recollect blowing things up in their basement lab, horrifying his mother. In fact, the decline of interest in science is often blamed on kids not having the same sort of risky chemistry sets.

The instruction manual for the 1936 Electro Experimental Kits begins, “We are living in a scientific age—one that is filled with magic but not the black magic of our grandfather’s day.” The other page cites Edison and Henry Ford as home experimenters who learned science in their basements. Click on the image to see it larger. (Via eBay)

“But then, when you do the research, you see stories of kids dying or having their hands ruined,” Onion continues. “I read a story about a kid who built a model rocket, and something went wrong with the launching system, and it went through his stomach. That’s not cute. There’s a tendency to be nostalgic for a less regulated time, particularly when toys haven’t caused this kind of event in several decades. And there’s a sexist tendency to blame the moms’ worries about it as an alarmist obstacle to creative play. Today, we have an obvious historical blindness that edits out the gruesome accidents.”

In 1958’s “The Space Children,” the children of scientists prevent a nuclear war by destroying the missiles their parents are working on. (Poster reproduction available on Walmart.com)

After World War II, Americans embraced the bounty of wartime scientific advances and a thriving economy: They now had cheap goods made out of high-tech plastic, streamlined appliances, and home TV sets. But they were also haunted by the specters of the A-bomb and the H-bomb. The burgeoning Cold War with the U.S.S.R. raised fears that workaholic Soviet scientists, laboring relentlessly under Communism, were making progress faster than American scientists, a competition that played out in the Space Race. Mainstream American pop culture attempted to assure people with images of the perfect suburban family defeating Communism through consumerism. However, American B-movies, comics, and pulp fiction were overrun with evil robots, monsters from space, radioactive mutants—and “mad scientists.” All of this affected how Americans regarded scientific education.

“The fears spiked in Postwar America at particular moments,” Onion says. “When Sputnik became the first spacecraft launched into orbit in 1957, Americans panicked, like, ‘Oh my God, the Soviets have it over us. Whatever the great powers of science and technology are, they’re better at them.’ That launch created a lot of apprehension and fear that kids absorbed and processed. Tons of postwar popular culture addressed that combination of wonder and fear, especially about nuclear technology and space travel.”

However, these fears were empowering for science-fiction loving boys like “Rocket Boy” Homer Hickam, whose life story is the basis for the 1999 movie “October Sky.” A 14-year-old living in West Virginia when the Russian satellite took off, Hickam felt he and his peers were “being launched in reply to Sputnik.” With his friends, he started a club called the Big Creek Missile Agency and began building rockets. The club garnered adoring press attention and eventually won gold and silver medals in the 1960 National Science Fair. Hickam grew up to become an engineer for United States Army Aviation and Missile Command and NASA.

“Homer Hickam was the son of a coal miner who became obsessed with space travel,” Onion says. “Before Sputnik, he felt that because he didn’t play football, he wasn’t valued at school. After Sputnik, the situation at school changed for him and his friends when the public started to see the Rocket Boys as the hope of the future.”

In Robert Heinlein’s 1959 novel Starship Troopers, boys take up arms and fight aliens alongside their fathers.

Space toys, model rockets, and science fiction exploring the wonders and possibilities of space travel were wildly popular with Baby Boomer boys, particularly young adult novels by Robert Heinlein—like 1949’s Red Planet, 1953’s Starman Jones, 1958’s Have Space Suit, Will Travel, and 1959’s Starship Troopers—that depicted teenage space adventurers who independently and religiously studied science.

While boys likely took this hobby as seriously as their fathers’ generation had taken their chemistry sets, another strain of marketing set out to placate mothers’ anxieties by convincing them space-obsessed kids were just adorable. Thus, the cute space cadet was born. The cover of Innocent Experiments features an image from the April 18, 1953, edition of “Collier’s” magazine depicting a blond, blue-eyed little boy in a space helmet holding a ray gun. He watches a butterfly that is somehow trapped in his helmet.

On this mid-century fabric, toddler boys and girls, as well as kittens, mice, and birds, make the Space Race look just adorable. (Via eBay)

“You would see women’s magazine articles about how to understand your space-cadet child, or how to talk to him, or why this interest is okay,” Onion says. “Telescopes were marketed to moms by presenting stargazing as an activity she could do with her son. I found an amazing picture at the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, from a brochure advertising a telescope. It shows a 10-year-old boy looking into the telescope and his perfect ’50s mother with a tiny waist and big skirt sitting adoringly at his feet. This ideal of wholesome fun and family togetherness was folded into the cute space-cadet cliché sold to women.”

Yet, when that space-cadet boy started to go through puberty, suddenly, there was concern he might be strange. Maybe he’s too interested in science and science fiction, and not interested enough in girls, parties, cars, or team sports. What if he grew up and became a mad scientist who turned rats into radioactive human-killing mutants?

“Before pubescence, it’s cute for boys to be interested in science,” Onion says. “After pubescence, it starts to get a little suspect. There’s a fear that your child is going to be that creepy B-movie guy.”

This page from a Starmaster Scientific Toy brochure depicts stargazing as an activity that brings the family together—even if the mom only watches her son use the telescope. Click on the image to see a larger version of it. (From Innocent Experiments, courtesy of The Strong)

Research on high-school attitudes published in 1957 by Margaret Mead and Rhoda Métraux and on college attitudes published in 1961 by David C. Beardslee and Donald D. O’Dowd showed students saw scientists in a negative light. Beardslee and O’Dowd found that students thought a scientist would be “unsociable, introverted, and possessing few, if any, friends” and would have “a relatively unhappy home life and a wife who is not pretty.”

Even before all the Cold War anti-science paranoia, the Science Talent Search, launched during the war in 1942, was designed to address the wartime concerns that the United States didn’t have the scientific “manpower” to face its enemies. It was funded by Westinghouse Electric Corporation, organized by scientists and journalists through a nonprofit called the Science Service, and run by journalists with an education in science. High-school students—both boys and girls—were encouraged to submit original research, and 40 finalists, of about 2,000 to 4,000 submissions, would travel to Washington, D.C., to compete for scholarship cash prizes. The contest continues today as the Regeneron Science Talent Search.

The finalists of the 1949 Westinghouse Science Talent Search pose on the Capitol steps. (Via Society for Science & the Public)

Besides the scholarship money, the finalists sent to Washington would attend lectures by and talks with prominent scientists, visit national labs, display their projects at the National Science Fair, field judges’ questions in panel interviews, and make media appearances. They would also have an opportunity to meet and take a photo with the President of the United States.

Back in the 1940s, the journalists running the Science Service were well aware of the stereotypes about anti-social science-focused adolescents, and set to debunk them out of the gate, Onion explains. Science Talent Search organizer Margaret E. Patterson said, “We were quite prepared when we invited the first 40 to Washington to greet a group of ‘brains’ with very little else to make them attractive, but we were pleasantly surprised … to find them just about the nicest people you could hope to meet—and thoroughly human.”

Two psychologists, Steuart Henderson Britt and Harold Edgerton were a part of the STS judges panel, and they came up with a test called the Science Aptitude Examination, which was a piece of the elaborate application process that included an essay and their transcripts. They also required the students to submit a “Personal Data Blank” that asked teachers to assess their “attitude-purpose-ambition,” “work habits,” “resourcefulness,” and “social skills.”

The 1962 B-movie “The Creation of the Humanoids” played upon stereotypes about mad scientists and technology gone awry. (Via WikiCommons)

“The people who were conducting the search wanted well-rounded students, someone that you want in your freshman class at a college because they’re very good in academia, but they allow themselves to also have lives,” Onion explains.

“We tend to see science as this mystical beast living in the sky that, somehow, children see more clearly because they haven’t been clouded.”

Reading the handful of Personal Data Blanks she found, Onion says, “A couple of the teachers who responded would say, ‘He’s not well-liked by his peers because he talks too much, and he just goes on and on’—he was basically a mansplainer. Science-fiction author Joanna Russ was a finalist when she was a senior in high school. A teacher wrote about her, ‘She takes on too many projects at once, and she tires herself out’ —what we would call ‘not having a good life-work balance.’

“After selecting the finalists, the Science Services would put out press releases that would say something like, ‘This husky farm-boy physicist is also a football player,'” Onion says. “Rather than debate whether a kid should be doing football or physics, their answer was to say, ‘Our kids do both.’ The female equivalent to ‘husky farm-boy physicist’ would be STS statements like ‘She’s very feminine.’ They would even mention that she wants to be a homemaker. ‘She may be interested in chemistry, but her heart is in the home.’”

It’s also hard to believe the Science Talent Search was the meritocracy it claimed to be in the mid-century, when you see how white the groups of finalists were. While the girls are in the minority, it was rarer to see a person of color among the bunch. And many professional scientists objected to the application process and rejected the idea that a great future scientist needed to be “well-rounded” or a popular athlete.

Scientists pose a threat to humanity in the 1936 film “The Invisible Ray,” which was re-released in 1948. (Via WikiCommons)

“A number of scientists wrote letters to the various scientific journals about the Science Talent Search asking, ‘Why does someone have to be a Boy Scout? I would have been considered super awkward and nerdy when I was young. You had asked me, whether I had friends, it would not have worked out,'” Onion says. “They felt that true scientists might be too fixated on their studies or nerdy hobbies to keep up a social life. The letter writers were worried about what might happen if the science community became too defensive. Like, if we insist young scientists are not dorky, where does that leave the ones who are dorky?”

While the Science Talent Search finalists—similar to Homer Hickam and his “Rocket Boys”—were trumpeted as the heroes who were going to defeat the Soviets with their smarts, some working scientists were annoyed the youth were receiving so much fanfare.

“Some of the speakers at the Science Talent Search would say, ‘You are the most important people in the United States right now. You need to stay with your studies,'” Onion says. “But some speakers would say, ‘Don’t get too big for your breeches.’ During his speech, famous astronomer Harlow Shapley went on a tangent about the importance of humility. He said when he was growing up, no one was telling him that he was the hero of the republic.”

In 1954, Science Talent Search finalist Marguerite Bloom (Burlant) watches as finalist Robert Rodden points “to the future.” (From Innocent Experiments, courtesy of the Society for Science & the Public)

While white girls participated in the Science Talent Search, it didn’t mean they had the same opportunities in STEM fields as the boys did. In the postwar era, working women were asked to step down from their jobs, hand the best positions to returning veterans, and prioritize getting married and raising children, often when they were just out of high school or college.

“Frank Oppenheimer created a place where the joy in science that he felt—which was by all accounts intense—could spread.”

“Even Robert Heinlein had been vocal during the war in his belief that female scientists should be included in the war effort,” Onion says. “He intervened on behalf of some women that he saw not getting jobs because of gender prejudice against them. But then after the war, adult women who did get scientific jobs lost them when the men came back. What happened to the Rosie the Riveters also happened in the labs.”

If you’ve seen the 2016 movie “Hidden Figures,” you know that even women who kept their jobs didn’t receive the respect they deserved. Mathematicians Katherine Johnson and Dorothy Vaughan and aspiring engineer Mary Jackson faced the double hurdles of racism and sexism when they worked for NASA in the 1960s. Johnson, for example, had to push to get her name on her own breakthrough discoveries or be allowed to sit in meetings and access crucial top-secret data. In labs across the country, women were often relegated to less-interesting low-paying science positions like being the lab assistant, number crunching, or keeping track of records or data. Onion says those postwar biases are reflected in the “Science Talent Searchlight,” a stapled mimeographed publication the STS sent its past finalists.

In the 2016 movie “Hidden Figures,” Katherine Johnson (played by Taraji P. Henson) works out essential launch equations for NASA in the early 1960s.

“Some of the most depressing material I saw in the archive were a couple of the Science Talent Science ‘alumni magazines,’ which had notes about what the past finalists were up to,” Onion says. “A lot of the guys were at Harvard, Cal Tech, or Berkeley, doing science. But most of the women would say something like, ‘I’d love to return to my scientific work, but I got married.’ Women who’d been STS finalists would end up actually supporting their husbands who were often also scientists—or at the very least staying home with the baby while the husband was getting his Ph.D. In the alumni magazine, women’s notes would often be little self-deprecating comments like, ‘I’ll get back to my research after I finish sweeping this floor.’ It’s clear that they missed their research but felt sheepish about it, which broke my heart.'”

Postwar women also received the brunt of criticism, as they had in the 1930s, for smothering their sons and discouraging independent scientific daring-do with “overmothering,” and thus hindering U.S. progress. As a result, some people advocated for the science education of girls.

“Education advocates would press for girls to learn science by saying, ‘They’re going to be raising the scientists of the future, so they should know something about it. We don’t want women in the home who are scornful of science. We want women who are willing to tolerate their basement being taken over or blown up by their sons,'” Onion explains. “Which is a whole different thing from supporting women who want to have careers in science.”

In 1958, A.C. Gilbert’s company realized they could make money selling chemistry sets for girls—as long as girls understood their place in the lab. (From Innocent Experiments, courtesy of the Chemical Heritage Foundation)

Prolific author Robert Heinlein asserted that women who were ignorant of science—particularly mothers, teachers, and school librarians—were holding back boys whom he felt needed to be ruggedly masculine, disciplined, and independent to reach great scientific achievements. He believed the teachers in the postwar era were ill-equipped to give boys the discipline and mastery they needed to pursue STEM careers. He said, “Our American public schools are today largely staffed by half-educated females and spiritually castrate males (who are just as ignorant).”

The few stories Heinlein wrote about girls that were interested in science usually ended with their return to the domestic life. In 1963’s Podkayne of Mars, Martian colonist Podkayne longs to become a spaceship captain, before she goes on a space adventure and gets kidnapped. When she meets a boy who also wants to be a captain, she starts to consider letting “a man boss the job, and then boss the man.” As she goes through puberty, she thinks, “One might say we were designed for having babies. And that doesn’t seem too bad an idea, now does it?” After helping with a ship’s nursery, she says to herself, “A baby is lots more fun than differential equations.”

In the ’50s and ’60s, though, some people were starting to question the American Dream of a nuclear family living in carbon-copy suburbs. Maybe all the convenient appliances and consumer goods generated by scientific developments were starting to cause moral rot?

In 1963’s Podkayne of Mars, Robert Heinlein made it clear he believed women were best-suited for child-rearing. (Via eBay)

“After the war, the degree to which the consumer market had created extreme comfort in people’s homes was mostly celebrated,” Onion says. “But in the ’50s, cultural critics started arguing that all of this comfort was problematic and that it created too much conformity. The argument, which is pretty misogynistic, was that married men would have to take jobs requiring a high degree of conformity just to provide their wives with the standard of living they were accustomed to. So people began to fear consumerism, too. Like ‘Oh God, now we have a market that’s giving us a new colored Formica counter top like every month. Will people who have these wonders want more of these wonders, and what will that do to our souls?'”

“The women would say something like, ‘I’d love to return to my scientific work, but I got married.’ … ‘I’ll get back to my research after I finish sweeping this floor.’”

As the Vietnam and Cold Wars progressed and climate scientists rang the alarm bells about pollution, consumerism, and overpopulation in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Americans started to feel hostile toward government-backed research and corporate-sponsored science and their potential to ruin the planet or kill us all with napalm or nuclear bombs. This led to a bifurcation: Oil and gas companies were giving museums big money that let them install pro-industry science exhibits with titles like “The Wonders of Oil,” which was similar to the chemistry-company propaganda that abounded in the ’20s and ’30s. At the same time, ecology magazines like “Ranger Rick’s Nature Magazine,” founded in 1967, warned children of horrors of oil spills while encouraging them with the efforts to clean up climate disasters. The magazine, published by the National Wildlife Federation, was a bleak twist on the nature-studies movement of the 19th century.

“I looked at a bunch of ‘Ranger Rick’s’ magazines from the ’70s, which actively addressed pollution,” Onion says. “An issue might have close-up pictures of the fish that died and washed up after a dam had been built. There would be a feature called ‘Ranger Rick and Friends,’ starring the magazine’s namesake raccoon. He and his animal pals would explore a swamp and find out it had been developed. Or they would stumble upon a stinky chemical spill and save birds covered by the spill.”

“Ranger Rick’s Nature Magazine,” published by the National Wildlife Federation, encourages kids to think about pollution and environmental solutions. (Via eBay)

However, a third way to approach children’s science emerged in 1969 when physicist and educator Frank Oppenheimer—brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer, one of the “fathers of the atomic bomb”—opened the free Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco. While Oppenheimer insisted his hands-on museum was not political (and it was certainly not pushing an environmental-activist agenda), you can see the influence of San Francisco’s counterculture with its hands-on funhouse-like exhibits that emphasized children’s play, exploration, and liberation. They could pop into a hall of mirrors, stand on an earthquake platform, or operate a giant lightning-shooting Tesla coil. These kids weren’t required to learn anything about science, even as they experienced the joy of gizmos displaying scientific principles.

“Before pubescence, it’s cute for boys to be interested in science. After pubescence, it starts to get a little suspect. There’s a fear that your child is going to be that creepy B-movie guy.”

“Frank Oppenheimer’s creation of Exploratorium was a way of reclaiming the utopian side of science,” Onion says. “Oppenheimer was opposed to typical science museums for a number of reasons, including that they were taking money from Big Oil. The answer, for him, was not necessarily to make a museum that was against oil or pollution, but rather to try to restore people’s joy in science. He thought Americans were depressed about science and technology because they didn’t understand it, so they were threatened and afraid of it. So he created a place where the joy in science that he felt—which was by all accounts intense—could spread. It was nothing short of a major social project for him. He wanted it to be a place where parents, kids, teachers, and scientists could be on the same plane, a pure place of experimentation.

“The Exploratorium allowed kids to move around and basically do whatever they wanted,” she continues. “When Oppenheimer saw families come to the Exploratorium with the parents taking charge and directing the kids like, ‘You have to come over here, and look at the things that I’m showing you,’ he was horrified by that. He felt that the kids’ excitement should drive the museum, not their parents’ desire for them to get educated.”

In the ’70s and ’80s, the Exploratorium became a model for hands-on science museums around the globe. “But it was not without criticism,” Onion says. “There were questions about how you measured children’s engagement and learning. And adults would get stoned and go to the Exploratorium to trip, unlike your typical science museum of the mid-century. You don’t want to take mushrooms and go to the American oil exhibit. At that time, it was free to go to the Exploratorium. Oppenheimer wanted it to be like a public park that a kid who doesn’t have money could visit as many times as he or she wanted. That also meant that drugged-out hippies went there. That freaked some museum people and teachers out.”

Frank Oppenheimer opened his free Exploratorium science museum in 1969. He wanted children to rediscover the joy he felt in science through fun, interactive exhibits. (Via Exploratorium.edu)

Today, the seemingly apolitical fun-science museum Exploratorium, which reopened in 2013 in a new location and costs $20-$30 admission, is more popular than ever. Online, stories about topics like planets, space aliens, and dinosaurs often go viral. And Trump’s anti-science populism has inspired a backlash of science cheerleading, including the March for Science on April 22, 2017. Having to cram a pro-science message on a piece of poster board, many marchers turned to images from their grade-school science textbooks, like atoms, dinosaurs, rockets, and periodic-table squares. Popular science is still popular, and slowly growing more inclusive: The Girl Scouts, for example, just added 23 STEM-related badges girls can earn to their program.

But in American politics, the high-school tough guys are running the show now, and the “brains” are being scorned. As Trump stacks his cabinet with friends of the oil and gas industry, fossil-fuel companies are even infiltrating public schools in states like Oklahoma, where some school systems are employing industry-created science curricula. Scott Pruitt, the climate-change denier in charge of the Environmental Protect Agency, is planning to install pro-coal exhibits in the agency’s museum, while a recent poll showed that Americans are more concerned about ISIS and cyber warfare than climate change. The Union of Concerned Scientists is circulating a petition that’s a letter to Trump stating, “As you forge a new path forward for America, it is vitally important that science and a respect for the facts guide your decision making.” More than a dozen professional scientists have been motivated to run for Congress in response to the president’s policies. American science is in a time of crisis.

“No matter how much lip service and respect people pay to science and technology, it’s perennially under-supported,” Onion says. “A large number of people who believe students should learn science and technology refuse to believe the large majority of climate scientists who say climate change is real. It goes back to the contradiction in the ’50s when people were saying, ‘Kids should learn science,’ but also, ‘Kids who learn science are dorks.’”

(To learn more, pick up a copy of Rebecca Onion’s Innocent Experiments: Childhood and the Culture of Popular Science in the United States, published by the University of North Carolina Press, Read more of her writing at The Vault blog on Slate. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Cyanide, Uranium, and Ammonium Nitrate: When Kids Really Had Fun With Science

Cyanide, Uranium, and Ammonium Nitrate: When Kids Really Had Fun With Science

The Government-Surplus Machines That Power a Cutting-Edge Science Museum

The Government-Surplus Machines That Power a Cutting-Edge Science Museum Cyanide, Uranium, and Ammonium Nitrate: When Kids Really Had Fun With Science

Cyanide, Uranium, and Ammonium Nitrate: When Kids Really Had Fun With Science Warning! These 1950s Movie Gimmicks Will Shock You

Warning! These 1950s Movie Gimmicks Will Shock You RobotsThe 1950s was a particularly good decade to be a toy robot. The world was g…

RobotsThe 1950s was a particularly good decade to be a toy robot. The world was g… Erector SetsAlfred Carlton "A.C." Gilbert, the entrepreneur behind the Erector set, was…

Erector SetsAlfred Carlton "A.C." Gilbert, the entrepreneur behind the Erector set, was… Space ToysSpace toys encompass everything from robots to rockets to ray guns. Primari…

Space ToysSpace toys encompass everything from robots to rockets to ray guns. Primari… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Americans are totally insane.

Industries find it convenient to denigrate health, environmental, and climate science while supporting materials, cybernetic, and energy science. It’s not cognitive dissonance; it’s greed.

Basically disagree. You are living in a culture that is obsessed with the products of technology and ‘progress’ and addicted to the culture of materialist capitalism that drives it. If you think science and technology is chronically underfunded, you should try working in the arts sector. It’s more philosophy, critical thinking and self-reflection that is needed. There is already more than enough research and evidence re. climate change, energy crisis etc. and the solutions out that quagmire. We already have the tools that we need. What is lacking is the moral gumption to use them.

why is an article on a collectors website so politically charged, go write for the communist news network. I’m here for information not a brainwash ! immediately deleting CW from my Bookmarks..

“While developments like electric light and disease-eliminating medicine were celebrated, the feeling the world was changing too fast created a suspicion of science and scientists that continues to this day.”

But only in America seemingly. Like our penchant for settling minor differences with guns, and unlike most of the rest of the developed world, our penchant for rejecting knowledge and belittling those who possess it is a deeply rooted part of American culture.

For a brief period from the end of WWII to the 1970s, we honored the advances of science and the scientists who made it possible. Albert Einstein was a household name and kids wanted to grow up to be astronauts and explore space. But not any more. Now we’ve reverted to type and have returned to egging on the schoolyard bully who beats up the smart kid for getting an A on the math test. No better example can be pointed to than the thousands of cheering and jeering people who attend Donald Trump’s rallies and roar in exaltation at his ignorance and lies. Only America puts rejection of knowledge on such a pedestal.