The spirits came calling in 1848. Through a series of startlingly loud knocks, a murdered peddler named Charles B. Rosna started talking to two teenage girls in their Hydesville, New York, home. Margaret and Kate Fox, who could be the inspiration for Wednesday Addams with their dark locks and solemn expressions, would ask the spirits questions out loud, and to everyone’s surprise, the spirits would answer.

“This created a sensation, not because there wasn’t a belief in spirits before—there obviously was—but because it seemed to prove the spirits were there and could be interacted with,” says Brandon Hodge, who runs a website called Mysterious Planchette that’s devoted to spirit-communication devices. “What was extraordinary and revolutionary about the Fox sisters was that they were rending the veil and establishing communication.

Above: Margaret, at left, and Kate Fox, with their much-older sister, Leah, right. (WikiCommons) Top: An image of a ghost at a séance in the May 12, 1888, edition of “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.” (Via MysteriousPlanchette.com)

“Mediums sprang up overnight as word spread,” he continues. “Suddenly, there were mediums everywhere. In the earliest days, you would sit down with a medium at a table, and you would start asking questions out to the ether. And these raps would signal ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in a simple binary code.”

In the emerging Spiritualist movement, new mediums, including the Fox sisters, started calling out the alphabet, letter by letter, to the rapping ghosts and thereby, spelling out words and sentences from beyond in an excruciatingly slow manner. But ingenious Victorians quickly started looking for ways to get the message faster, coming up with all sorts of means and devices to chat with the dead. Hodge is a collector of such devices, focusing on “planchettes” or writing tools that supposedly helped the spirits jot down their thoughts.

It’s a particularly hot topic at the moment with the recent “Ouija” horror movie—which hinges on the “Ouija boards are evil” meme that makes Hodge cringe. And by the end of next year, Hodge, a former magician who owns Big Top Candy Shop and Monkey See, Monkey Do! toy store in Austin, Texas, hopes to put out the authoritative book on the subject, tentatively titled Talking Tables & Scribbling Spirits: A Complete History of Spirit Communication Tools, with his collaborator, Ouija board expert Robert Murch.

Hodge says that most spirit-communication concepts started out with serious religious intentions, but eventually got co-opted by popular culture as playthings or curiosities. “The Spiritualists come up with these devices and use them to communicate with the dead. Then, pop culture comes along and goes, ‘Oh, look what they’re doing over here.’ And entrepreneurs with vision and foresight take these devices, market them, and suddenly, they become a huge parlor hit.”

Brandon Hodge, the creator of MysteriousPlanchette.com, with his collection of Victorian spirt-communication devices. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

As laypeople experimented with these devices at home, others turned to Spiritualist mediums, a job that eventually gave young women—who were thought to be so receptive to the divine they would come to embody the spirits themselves—power they couldn’t have dreamed of before. These mediums were able to flagrantly violate strict Victorian social taboos and speak unpopular or radical opinions.

Spiritualism, simply defined as the belief that souls continue to exist after death and that it’s possible to talk to them, wasn’t born in a vacuum. In the century before, a German doctor by the name of Franz Anton Mesmer introduced the concept of “animal magnetism,” the theory that an invisible force or “magnetic fluid” flows through human and animal bodies. As Mesmer’s medical theories were disproved, his techniques were adopted for spiritual healing purposes, and in 1843, James Braid, a follower of the late Mesmer, invented what we know of as hypnosis or mesmerism.

In the mid-1800s, the Western World was in flux as more and more scientific discoveries, like the theory of evolution, were undermining the biblical creation story, and by extension, the existence of God. People were becoming disillusioned with the church and, at the same time, felt suspicious of science.

Spirit rapping was so popular, by 1853, T. Ellwood Garrett and W.W. Rossington published a song about it, via sheet music. (From the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library at Duke University)

“At the moment of this crisis of faith that was happening all over the Western world, there was this incredible investment in ghost stories,” says Marlene Tromp, author of Altered States: Sex, Nation, Drugs, and Self-Transformation in Victorian Spiritualism. “It was a profound response to anxieties about God and whether there’s an afterlife. If you could prove there was life after death, well, that changes the whole game. Most Spiritualists talked about the moral or heavenly impulse behind the afterlife. Communication with the dead was seen as proof of God.”

Upstate New York became a magnet for folks looking for new ways to find meaning in life. Thanks to the Fox sisters, Spiritualism was also born in that region of New York, known as the “burned-over district.”

“The burned-over district of New York was a hotbed of religious activity,” Hodge says. “The Shakers came from that region. Mormonism has its roots there. It had mesmerists and traveling phrenologists. Influential Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis grew up there. The people there were said to have been converted so many times that there was no more faithful fuel for the religious fires. It was also a center of progressive sentiment. The women’s suffrage movement and the anti-slavery movement were popular in this region as well.”

This 1920 “spirit photo” by William Hope claims to show a spirit hand moving the table. (Via the National Media Museum’s Flickr page)

As news of the Fox sisters spread, newly minted mediums took to communicating with spirits through raps. The belief was that spirits, though non-corporeal, had the ability to excrete a material from the medium called “ectoplasm”—not unlike the “magnetic fluid” in mesmerism—part of the veil between worlds that allowed the ghosts to physically interact with the living. An ectoplasmic tendril might, for example, reach out and produce a shockingly loud knock.

“A medium would call the alphabet out to the air, and when the proper letter was arrived upon, a knock would ring out, she would confirm it and then write it down,” Hodge says. “In this way, sentences, words, or phrases could be formed and communication established. But that gets awfully tedious. A lot of mediums would lay down a board or a card with an alphabet written on it. Instead of calling out the letters, they would have a pencil and would sweep it over the letters until the raps told them to stop. The descriptions of these raps are fantastic. Even the skeptics who tested the mediums were amazed at the loudness. The mediums would be up on stage, with no microphones or amplifiers, and the entire audience in these theater halls could hear multiple choruses of raps ringing through the hall.”

In the 1910s, magician William S. Marriott demonstrates how he could make a table appear to levitate with his foot. (From the Mary Evans Picture Library/Harry Price)

Before long, word got out that if you and your friends or family put your hands on a small- to medium-sized table and waited, it would eventually start moving. Naturally, people believed it was the spirits trying to communicate, through what became known as “table-tipping” or “table-turning.” A scientist by the name of Michael Faraday studied the physics of the phenomenon in 1851 and concluded that the sitters were, in fact, unconsciously moving the table, a phenomenon now known as the “ideomotor response,” but his findings didn’t deter anyone.

“In the first few years of Spiritualism, you had to go see a medium if you wanted to experience spirit rapping,” he says. “You hoped one came to your town, so you could pay 50 cents and sit in at a séance. Our earliest evidence shows that tables and chairs started mysteriously moving in the presence of the Fox sisters. Before long, the Spiritualists were attributing the movement of the tables to the spirits. Then, the information got out there that any family could sit around their kitchen table, clear off the silverware after dinner, and put their hands on it and if they waited long enough, it would start to move on its own. You could ask the table questions, and it would rap out responses. You could do this alphabet-calling thing that the mediums had been doing.”

This 1865 broadsheet reads, “These Pictures are intended to show that Modern Spiritualism of A.D. 1865 … was described and practised thousands of years since under the names of Witchcraft.” (Via WikiCommons)

Early believers had no problem going to a séance on a Saturday and going to church the next morning, because Spiritualism layered neatly over the Christian belief in souls, God, and the afterlife. Of course, some priests weren’t too happy about it. “There are early attempts by the clergy to rail against Spiritualism saying, ‘No no no, you’re doing something very bad,’” Hodge says. “Mostly, they said you shouldn’t be disturbing the souls of the dead. There was a little talk of demons, but certainly not on the level that we see in modern times.”

“A séance brought people together and enabled them to face their fears. Men and women would sit in the dark in close contact, and they would have no idea what was going to happen.”

Marlene Tromp, who is also the Dean of Arizona State University’s New College of Interdisciplinary Arts, explains that in some households, holding séances became a regular family practice. “A typical séance would involve people gathering in a darkened room, and they would pray or sing, essentially inviting the spirits to come and speak to them,” she says. “In the family settings, it could happen any time of day or night; it might be very frequent. It varied a great deal from family to family. Often, they would sit around a table and hold hands because that was supposed to guarantee that nobody could do anything shady like, say, shake the table with their own hands.”

Jill Tracy—a San Francisco singer and composer who, with violinist Paul Mercer, performs a touring improvisational-music show called “The Musical Séance”—says that Victorians were more open about loss of life and honoring the dead than we are now. At The Musical Séance, she and Mercer will spontaneously compose pieces based on sentimental objects the audience brings in—from antlers and dentures to haunted paintings and cremated cats to swords and a lock of hair from a drowned boy—not to call in spirits so much as memorialize the audience’s loved ones.

Jill Tracy, left, and Paul Mercer perform a “Musical Seance.” (Courtesy of Jill Tracy)

Tracy says even as a parlor pastime, Victorians had a sweet, romantic side to them. “A séance brought people together,” she says. “It enabled them to face their fears because it was being pitched to them as a form of group amusement, instead of a frightening experience where one sits in their house alone and tries to talk to a spirit. A séance was also sensually charged, the true definition of arousing the senses. Men and women would sit in the dark in close contact, often holding hands or touching, and they would have no idea what was going to happen. For Victorians, it was almost an acceptable moment of abandon.”

“Séance sitters would say that a person was levitated out of the room and out a window and in through another window of the house.”

Even though Victorian families who had experienced loss were very earnest about their beliefs in Spiritualism, Hodge says, by 1853, table-tipping became a fad on par with Furbies, or even the more recent Internet meme known as planking. “The newspaper headlines that summer were just all about the tables tournantes, or the turning tables. You’d see committed Spiritualists taking very seriously every rap and scrape of the table because its message was from the beyond. Your dead great-grandmother was giving you a message. On the other hand, you had people who just thought it was funny. It became a parlor game. That’s the first transfer of Spiritualist belief from the religious side into the popular-culture side because you didn’t necessarily have to be a committed Spiritualist to put your hands on your dinner table and experiment with it. It’s fun. I suggest anyone reading try it.”

But table-tipping at home had nothing on the spectacles that Spiritualist mediums started to put on. “Sometimes people would report fruit falling from the ceiling or food appearing on the table or flowers showering from the ceiling,” Tromp says. “Séance sitters would say that a person was levitated out of the room and out a window and in through another window of the house.”

An engraving from the April 2, 1887, edition of “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper” shows a séance with a floating guitar and a spirit hand writing messages. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

In the early 1850s, Jonathan Koons, a farmer deep in the country of Athens County, Ohio, set out to debunk a nearby medium but instead became converted into a believer. “Once he started communicating with them, the spirits told Koons to build a room and they would come, sort of like ‘Field of Dreams,’” Hodge says. “He also built this incredible spiritual machine, a modified table that was supposed to act as a battery to let the spirits manifest within this room.”

According to reports, the spirits asked Koons to supply this room with musical instruments: a tenor drum, a bass drum, two fiddles, a guitar, an accordion, a trumpet, a tin horn, a tea bell, a triangle, and a tambourine. Koons started hosting free public séances with his wife, Abigail, and his eldest son of nine children, Nahum—both of whom were believed to be gifted mediums. According to The Haunted Museum, visitors reported that when Jonathan Koons played the fiddle, the other instruments in the room would join in, playing strange melodies in time while they danced above the sitters’ heads.

Multiple instruments dance at a séance in another illustration. (Via JennMcQuiston.com)

“The descriptions of the Koons’ spirit room are just fantastic,” Hodge says. “There were instruments strewn about the room, the spirits would pick up these instruments in the darkness. Suddenly, there were violins and drums and triangles floating above your head and making this tremendous racket. Then, the glowing hands would manifest. You could feel them stroke your face, and they’d drop off into nothingness at the elbow. Jonathan Koons didn’t charge for admission either; it was a free show if you showed up at his farm. It sounds incredibly entertaining, even from a modern perspective.”

Visitors to the Koons’ séances also reported that the glowing disembodied hands would touch their own hands and vanish. Sometimes these hands would even rapidly write out messages. The spirits also gave speeches, with a little help from Nahum.

“Our evidence suggests Nahum Koons came up with the idea to use a speaking trumpet to transmit the voices of spirits to the assembled séance sitters,” Hodge says. “The belief was that the spirit was manipulating the medium’s vocal cords, which is awfully convenient. But the spirits were said to do so very lightly, producing whispers. The spirit trumpet was used to magnify the whispers of the spirits. At first, they take the shape of simple horns about 2 feet long and about 4 inches in diameter at the bell end. The later examples are segmented and telescope out 2 or 3 feet. They would have these luminous glow-in-the-dark rings on the end of them so you could see them in the dark séance room.”

Brandon Hodge has built an impressive collection of spirit trumpets. He found one dismantled in a wheelbarrow outside an antiques shop. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

“The Victorian gender stereotype was that women were more passive and their heads were more empty—so a spirit could more easily go through them.”

“My favorite device is the spirit trumpet,” says Tracy, who went to visit Hodge’s collection of devices this month. “When the spirits were not present anymore, the trumpet, tambourine, and other instruments would crash to the floor. I love that imagery. In some cases, a medium would use a music box. If the music box would start to play, then the spirit was in the room. So there’s this beautiful connection between music and the other side.”

Speaking through Nahum’s spirit trumpet, the spirit who seemed to be in charge was called John King—even though he was thought to be 17th century Welsh pirate Henry Morgan—yes, that Captain Morgan. John King claimed to be the one who corralled more than 160 spirits in the Koons’ spirit room where they were making such a clamor. He and his daughter, Katie King, were fixtures at seances for decades.

“A spirit guide is a particular spirit to which a medium is strongly attached,” Hodge says. “The spirit guide acts as the medium’s conduit to the beyond and has the ability to introduce them to other spirits. It was very popular for a medium to have a wise spirit guide that was literally their guide through the spirit world.”

The Davenport Brothers’ manifestation cabinet is depicted in an image from Henry Ridgely Evans’ 1902 book “The Spirit World Unmasked: Illustrated Investigations Into the Phenomena of Spiritualism and Theosophy.” (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

John King was also the spirit guide for the young brothers Ira and William Davenport, when the two started putting on shows in 1855. Onstage, the Davenport brothers introduced the concept of the “manifestation cabinet.” According to The Haunted Museum, they would have an audience member tie them up with ropes inside the cabinet, and while the brothers were out of sight, all sorts of spooky phenomenon would take place, including the appearance of disembodied hands, ghostly forms, and floating instruments playing so-called “spirit music.” But when the lights came up and the cabinet doors flung open, the brothers would always be tied up as before.

“This would be the modern equivalent of Neil deGrasse Tyson going on ‘Cosmos’ and saying, ‘I just ran all these tests, and Heaven’s for real.’”

At this point, Spiritualism was only 7 years old, but Hodge says that the innovative and sensational shows put on by the Koons family and the Davenport brothers spelled the beginning of the end of the movement.

“It was the birth of a new phenomenon and simultaneously the death knell of Spiritualism,” Hodge says. “In later years, manifestations had to become increasingly sensational. People weren’t going to séances and listening for rapping ghosts with mediums anymore. People went to séances to see ghosts. The more that public demand flowered for that type of sensation, the more mediums—assuming we believe that this was fraudulent activity—had to resort to more and more extreme means to produce these effects. These included full-form materializations where you actually have walking ghosts coming out of the cabinets.”

Tracy believes that in the early days most mediums had sincere intentions. “I would assume in beginning it was mostly people who had some integrity and were trying to help people communicate,” she says. “Then, as Spiritualism became more of a trend and once making money became the motivation, it just got more and more fraudulent. And as with any fad, people started just jumping on the bandwagon.”

This “What Does Planchette Say?” device was produced by the London toy company Jaques & Son in 1900. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

Since the concept of performing full-body manifestations took some time to spread, alphabet-calling was still common in the 1850s. Isaac Post, a friend of the Fox sisters, was the first to perform what’s known as “automatic” or “passive writing,” letting a spirit write messages through him—which, like using a spirit trumpet, is a suspiciously easy way to deliver messages from beyond. Then in Paris in 1853, the spirits requested that a medium jettison the tiresome alphabet-calling technique in favor of a tool that would let them write through more than one person. Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail, a French educator who wrote under the pen name Allan Kardec, established the Christian philosophy of “Spiritism,” distinct from the more open-ended belief system of “Spiritualism.” Kardec described the séance in which the planchette (French for “little plank”) was invented.

“Allan Kardec reported that during an alphabet-calling session on June 10, 1853, the spirits actually said, ‘Hey, grab a basket, turn it upside down, put a pencil in it, everybody put their hands on it, and it will write out messages,’” Hodge says. “That basket with the pencil in it would quickly evolve into an oval- or heart-shaped board with two wheels and a hole in it for a pencil. A cottage planchette-making industry sprang up in Paris, before it jumped the channel over to the U.K. and eventually to America in 1858.”

The year the planchette was invented was also the year table-tipping exploded and the Koonses were starting to get attention for their spirit phenomena. “1853 was a hugely formative year for all this because by that time, the news of the Fox sisters had spread,” Hodge says. “Belief in spirit communication had increased exponentially, and people were looking for means to expedite it.”

Hodge’s display features three G.W. Cottrell planchettes from the 1860s. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

For Parisians, planchettes, usually made by cabinet makers, had the obvious bonus of allowing men and women to sit close and touch lightly. In London, scientific-equipment makers Elliot Brothers and Thomas Welton, a prosthetic limb manufacturer whose wife was a crystal gazer, were among the earliest manufacturers of planchettes. In 1858, Henry F. Gardner, a devout Spiritualist leader, and Robert Dale Owen, a Spiritualist who had served as a U.S. Congressman and whose father founded a utopian community, traveled to Paris and London, visiting séances. They returned to the United States with six planchettes in tow; Gardner gave one to Boston bookseller G.W. Cottrell. “And Cottrell makes a batch of 50, according to some of the reports,” Hodge says. “They don’t sell. They sit on the shelves in his little Boston bookstore.”

That’s because the Civil War was brewing, and Americans had more on their minds than parlor games. Once the fighting ended, though, interest in Spiritualism surged again as people were desperate to connect with the young men they lost too soon because of the war.

In 1867, a British magazine called “Once a Week” published a writer’s detailed experience of receiving miraculous revelations while using a planchette over several séance sittings. Thanks to the Associated Press news service, the article was republished in myriad newspapers in the United States and Europe. Suddenly, everyone had to have a planchette. Hodge says by 1868, the planchette had become a widespread fad on the level of yo-yos or Hula Hoops.

“The story was so sensational and so lively that passages would be reprinted as a paper insert for planchette boxes and as fliers for the sale of planchettes well into the 1920s and ’30s,” Hodge says.

“How many people got to feel up a woman in the 1870s in public with permission—with their neighbors watching?”

In the United States, mostly stationers and booksellers produced and sold planchettes, which were usually beautifully made objects. “Thomas Welton in London wrote in a letter to the editor to remind people that he’d been making these for years,” Hodge says. “G.W. Cottrell in Boston did the same thing. Because once the article hit American shores, manufacturers just exploded. Kirby & Co., a bookstore in New York City, is probably the most famous of all planchette makers. They produced three different wooden models, starting with the basic model and then two with increasingly filigreed wooden boards and castors. They also produced an India-rubber model and a plate-glass planchette. I have the only known surviving plate-glass specimen from 1868, which sold for the hefty sum of $8.

“Bangs Williams made a fantastic shield-shaped planchette that concentrated on the animal-magnetism aspects, harkening back to the mesmerists,” Hodge continues. “They would screw the castors into these little rubber spacers to insulate the wood from the metal of the castors, so you would get a ‘clean charge’ on your planchette before using it.”

A Bangs Williams “Insulated Planchette” from 1868 has rubber spacers between the castors and the board. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

But as soon as the public took to planchettes, Spiritualist mediums largely abandoned them. Boston engraver William Mumler introduced the trend of “spirit photography” in the early 1860s, when he discovered how to double-expose a photograph. At spirit parlors, clients would have a session with a medium where they’d describe the person they hoped to see, and then, they would pose for a photograph. When they received the image, a hazy, misty person in white who vaguely resembled their beloved would be hovering in the background. Some of Mumler’s “spirits” were discovered alive walking around Boston, and he was tried for fraud in 1869. However, the belief in the powers of spirit photographers like Frederick Hudson, Georgiana Houghton, and William Hope carried on well into the early 20th century.

“When you look at a spirit photograph now, it’s so obviously fake, and maybe we know that because we have technology like Photoshop,” Tracy says. “Maybe back then people couldn’t even fathom that you would fake a photograph. And there was a desire for marvel and childlike wonderment that I think is sadly lost today. I miss that about the world, that belief in monsters, folklore, and ghost stories. But there’s part of us, I think, that wants to keep that magic and mystery alive.”

So-called ghosts lurk in William Mumler photos of an unidentified young man, left, and John J. Glover, right. (Via WikiCommons)

During the 1860s and ’70s, up-and-coming Spiritualist mediums hosted increasingly spectacular séances in dim-lit rooms. While many men were mediums, the movement gave young women a unique platform because spirituality fell under the domestic realm women were thought to excel in. “The Victorian gender stereotype was that women were more passive and their heads were more empty,” Tromp says. “So a spirit could more easily go through them, right? A man might get his own thinking involved, but with a woman, that’s not a problem. It was something that you could do and retain your femininity, whereas if you wanted to be, say, an accountant and you were a woman, maybe that would be a problem. As a medium, you can say, ‘The higher spheres are speaking to me, and there’s nothing more important and valuable than that, so you have to listen.'”

“Public mediums” collected change from séance sitters, and were more likely to be considered fakers. “Private mediums,” on the other hand, were often women originally from a working-class background who worked for rich people, holding séances in exchange for room, board, and other gifts. Some celebrity mediums were regularly invited to travel abroad to host séances, all expenses paid.

Sometimes these mediums performed “apportations,” where tokens from the spirits like food, flowers, seashells, or small coins would appear out of thin air. Even more popular were flesh-and-blood materializations: The medium would go into a manifestation cabinet, which was often a wooden wardrobe or even a corner of the room, covered in a heavy velvet curtain. The spirit would emerge from the cabinet, looking an awful lot like the medium in a loose muslin robe and veil, what was known as “spirit drapery.”

An attorney named Henry Steel Olcott investigated two brothers, William and Horatio Eddy, who were Vermont farmers that claimed to have incredible medium powers. He wrote a 1875 book about it, “People From Other Worlds,” and included this example of spirit writing. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

“It obviously begs the question: Is a medium still back there?” Hodge says. “Or is the medium now walking around on a muslin robe, pretending she is a ghost? That’s what most exposés discovered.”

But the Spiritualists had an explanation for why the manifested spirits looked so much like their mediums. “The idea was that the medium was supplying ectoplasm—believed to be a combination of energy and matter—from her body for the spirit to inhabit,” Tromp says. “So the spirit would use some part of that medium’s body and energy to produce a body for him or herself. At the time, photography was a new phenomenon, too. And photographs had to be developed in a darkroom or it would destroy the plate. Mediums would argue you couldn’t open the curtain and expose the medium to light while she was ‘developing’ the spirit, because it could harm the spirit and the medium herself.”

You’d think it would be perhaps easier to see ghosts if you were drunk or high on drugs. But some mediums insisted that their séances sitters be completely sober. “Elizabeth d’Esperance wouldn’t let people drink or intake anything that could be mind-altering for six months before a séance,” Tromp says. “She was saying, ‘If we’re going to experience something, it’s everybody in the room that’s responsible for it, not just me. If something goes awry, you guys are all a party to it. This isn’t a game. We have to take this very seriously.’ Her career lasted longer than a lot of the other mediums’. I think that had a lot to do with the way that she conducted séances.”

George Sitwell’s illustration shows a “spirit grabber” snatching Florence Cook’s ghost while another debunker finds her manifestation cabinet empty. (Via VictorianGothic.com)

In fact, many mediums expressed concern that negative energy could influence the séance, calling forth a mean, devious, or lying spirit. “So they’d say if a doubter or debunker was in the room, the séance might not produce any spiritual phenomena,” Tromp says. “When Catherine Wood had a particularly bad séance, she explained that a bunch of drunk men jostled her on the way there and it messed up the spiritual aura.”

“Suddenly, there were violins and drums and triangles floating above your head and making this tremendous racket. Then, the glowing hands would manifest.”

Séance sitters, while they might be very religious, would also arrive expecting a certain amount of titillation. “The intimacy of the séance is one thing that drives not only the popularity of mediums—particularly when they’re attractive young women like Florence Cook, or Kate or Maggie Fox—but also the popularity of the planchette and, later, the talking boards,” Hodge says. “Everyone’s seated around a table. The lights are dimmed. You place your fingers on the table, and everyone overlaps pinkies. You’ve got a woman prancing around the room in a glow-in-the-dark muslin sheet and nothing else on underneath. And they would say, ‘No, really, reach out and touch the ghost. You can feel her.’ How many people got to feel up a woman in the 1870s in public with permission—with their neighbors watching?”

The mediums materialized a handful of spirit guides over and over—and these “familiars” would introduce them to the other spirits that happened to be in the room, such as a sitter’s dead son or daughter. The medium Florence Cook, who became a celebrity in the 1870s, always materialized Katie King, believed to be the daughter of pirate spirit John King, who was so popular at the Koons’ and Davenports’ séances. As they were straddling two realms, the materialized spirit guides could glibly ignore Victorian social mores.

Henry Steel Olcott met medium Madame Helena Blavatsky at the Eddy farm. Pictured in 1888, the two were instrumental in forming the Theosophical Society, an attempt to integrate world religion, reason, science, and Spiritualism. (Via WikiCommons)

“The spirits would behave in ways that sometimes would cause people to think, ‘That’s just scandalous! Now, why would a spirit do that?'” Tromp says. “But of course, they’re the spirits of humans, the mediums would argue, and they have human flaws, although they’re on a spiritual path now.

“Imagine this in a Victorian living room: The female spirit comes out of the cabinet, and she says to the male sitters, ‘Kiss me and touch my hips,'” she continues. “So the men would be feeling her waist to make sure there was no corset. And the spirit would be kissing, hugging, and sitting on people’s laps. In a Victorian living room, it’s just outrageous. Imagine it happening in a living room now, and it’s still outrageous.”

Sample of automatic writing by medium Hélène Smith, which she claimed to receive from Martians, as found in Théodore Flouroy’s 1897 book, “From India to the Planet Mars.” (WikiCommons)

Aside from caressing and smooching the sitters, some spirit guides engaged in playful taunting. “If you bothered the medium, maybe the spirit would come out and whack you in the head,” Tromp says. “That was because the spirit was protecting the medium. Annie Fairlamb Mellon used to materialize a child spirit named Cissy, who would put her hands in people’s pockets and take watches and other trinkets. Florence Cook’s Katie King also took things out of people’s pockets, and she was full-grown woman.”

The spirit guides could also speak freely on topics that were considered taboo. If the mediums were just putting on elaborate pieces of theater, the materializations gave women the means to get their voices heard in a way they never would have before. Saying their ideas came from a higher power gave mediums substantial influence over social and political beliefs: They could inject ideas about poverty, women’s suffrage, domestic violence, or the abolition of slavery into the public consciousness.

Cora L.V. Tappan, circa 1857. (WikiCommons)

“For a working-class woman who becomes a medium and ends up hanging out in wealthy people’s living rooms her entire career, it was an opportunity for another kind of life,” Tromp says. “And it was also an opportunity for women to speak in fora that they usually didn’t have the opportunity to speak in. For example, an American medium named Cora Tappan traveled all over the world—the U.K., Australia, the U.S.—and gave lectures on things that women typically didn’t speak on. She would draw hundreds and hundreds of people to these lectures and talk about everything—politics, legislation, ethics, morals, diet, and science. She talked about whatever she wanted because she could say, ‘Oh, the spirits are guiding me.’

“When Florence Cook was newly married, her husband said, ‘I don’t think you should be a medium anymore now that we’re married because I don’t want you to work,'” she continues. “And she said, ‘Nope, the spirits tell me I should keep at it, sorry.’ In that way, she wasn’t resisting her husband. The spirits are speaking on behalf of God so, of course, she has to go do it. So she still got to travel, have her séances, and do these big performances where she’s center stage.”

Some female mediums, like Catherine Wood, materialized bearded-male spirit guides. “There was a lot of boundary-crossing that went on in materialization,” Tromp says. “Whether you believed or thought they were faking it, essentially what they’re doing is performing manhood, which suggests that manhood is not innate, natural, and secure but performed.”

In addition to blurring gender roles, mediums often explored cultural boundaries. “We were still in a period of Indian Wars and shuffling Native Americans off to reservations,” Hodge says. “Yet, oddly enough, it was very popular to have a sagely Native American spirit guide. Black Foot was a popular one, as well as Red Chief and the Red Cloud. It’s certainly a paradox.”

This 1872 spirit photograph shows Mrs. Pearson with the purported spirit of her sister, as manifested by the medium Georgiana Houghton. Photo by Frederick Hudson. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

In the United Kingdom, spirit guides were more likely to be from India, a country colonized by the British. In her book, Altered States, Tromp argues that mediumship gave women license to express their anxiety about the impact of colonization. A newer book by Christine Ferguson, Determined Spirits: Eugenics, Heredity and Racial Regeneration in Anglo-American Spiritualist Writing, has a different take.

“Ferguson argues that it wasn’t anxiety about imperialism; it was just exploitative,” Tromp says. “That reading is clearly there, too. One of the things I say in the book is it’s not like this was all just peaches and cream. Just because you’re materializing Indian spirits doesn’t mean that now you think Indians are equal. But if you’re saying that an Indian can inhabit a white woman’s body, there’s a blurring of identities there.”

Florence Cook’s Katie King. (Via VictorianGothic.org)

Séances became so popular in the 1870s they piqued the interest of prominent scientists. “Germ Theory was proposed in the 19th century, and you couldn’t see germs,” Tromp says. “At the time, scientists were discovering all sorts of phenomena that were not visible to the naked eye but were a kind of energy or matter. Some scientists thought Spiritualism was just a bunch of chicanery, and some scientists were more curious and open to discovering new unseen forces.”

The more curious scientists developed test conditions for these materializations, in attempts to prove the spirit wasn’t just the medium walking around in spirit drapery. “They might tie a medium to his or her chair with ropes or chains and seal the knots with signet rings,” Tromp says. “One medium, the scientists nailed her hair to the floor.”

One of the more open-minded takes on the séance phenomenon came from a member of the Society for Psychical Research, which tried to approach Spiritualism from neutral point of view.

“He writes that he sees this materialized ghost come out of the materialization cabinet, and he thinks it looks exactly like the medium,” Tromp says. “He can’t understand why anyone wouldn’t see that. But he said, ‘The person to the left of me sees her long lost mother, and the person to the right of me sees a cousin that she’d tragically lost in an accident.’ And he said, ‘It’s no question that those people believe, so I have to have humility because the depth of their belief is so profound. Is there something that they can see that I can’t that because that spirit is speaking to them?'”

Other less-patient debunkers would infiltrate a materialization séance and simply light a match when the spirit came close enough to see her face. On rare occasions, rival mediums also threatened to wreak havoc at one another’s séances. “There was a rumor circulating that associates of a medium’s competitor were going to come to one of her séances. And when her spirit came out of the cabinet, they were going to throw acid in the face of that spirit. Whether you believed that that was an actual flesh-and-blood spirit or not, that would harm the medium because you believe they were connected and were really one body. That never happened, to my knowledge.”

But aggressive debunkers known as “spirit grabbers” would seize the spirit and throw back the curtain to see if the medium was still in the materialization space. These exposures often ruined a medium’s career. But a medium could try to redeem her reputation somewhat by submitting to rigorous scientific tests.

Florence Cook manifests Katie King outside her cabinet and with Sir William Crookes. (From the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition catalog, “The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult”)

“Florence Cook—known for manifesting John King’s daughter Katie King—suffered an exposure and then she went to a very famous Nobel Prize-winning scientist, Sir William Crookes, to prove that her mediumship was real,” Tromp says. “He found an element that’s on the periodic table, founded the ‘Quarterly Journal of Science,’ and developed the Crookes tube, used in distillation in chemistry. She knocked on his door and said, ‘I would like to submit to any test that you can develop to prove that I am authentic.’ She actually was under his roof for weeks, doing all sorts of testing in his home with his family, and in the end, he authenticated her mediumship. People have looked back on it and said, well, he was just having an affair with her, of course. But it seems to me he may have actually been a believer. He was advised by his colleagues against publishing any of his writings on Spiritualism because it would make him look kooky, but he did publish some of it.”

Because the public now expected to see really wild things when they attended a séance, materializations and the resulting exposures were becoming a wedge issue for Spiritualist in the 1870s. “Some Spiritualists started saying, ‘Enough of this,’ because too many people were being caught as fraudulent mediums,” Tromp says. “The same media that built up this fad was very quick to tear it down.”

An early planchette in Brandon Hodge’s collection with its box, maker unknown. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette)

Even Maggie Fox, one of the originators of Spiritualism, came out against the movement in 1888, explaining the various ways she and her sister, Kate, would make the raps themselves. Apparently, the sisters were gifted at loudly cracking their toes and knee joints; skeptics had noted the noises seemed to originate under their large petticoats, but the doctors investigating them were not allowed to reach under their long skirts and touch their ankles. Tromp says that Maggie later recanted her recantation, saying she had denied Spiritualism for money because she was so desperately poor.

The growing anti-Spiritualist sentiment affected the market for planchettes, too; they were taken less seriously as spiritual tools. In the 1870s, anti-planchette exposés like “The Three-Legged Imposter” or “Confessions of a Reformed Planchettist” were published. By the 1880s, the stature of the planchette was so diminished that toy companies like Selchow and Righter and E.I. Horsman in the United States and Chad Valley Toys, Glevum Games, and Jaques & Son in the United Kingdom became the primary movers in the planchette market.

The original Ouija planchette from 1890 is a smaller pointer version of the writing planchette, with little legs instead of two wheels and pencil. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

While it was fun at first, trying to decipher the scribbles made by the planchette got to be almost as tiresome as alphabet-calling. But the concept of the talking board was finally taking shape in 1886, as illustrated news reports showed “the new planchette,” used as a pointer on a board with the alphabet on it. Around the same time, two men in Chestertown, Maryland, E.C. Reiche and Charles Kennard claimed to come up with the idea individually, but worked together on a prototype. Kennard moved to Baltimore, went into business with fellow Masons, and patented the infamous “Ouija” board designed by Elijah J. Bond in 1891. Soon, Kennard’s Ouija boards were all the rage, leaving the writing planchette in its shadows.

It took nearly 40 years for manufacturers to combine Spiritualist alphabet-pointing with the motion of the planchette, but in that time period, many inventors had come close to the device we now know of as the Ouija board. “Isaac Pease’s ‘Spiritual Telegraph Dial’ from the 1850s is one of my favorite devices,” Hodge says. “It’s an 8-inch square box, and it’s got a little dial clock hand in the middle and letters and numbers printed around it. You put it on the table, and then you put your hands on the table so it tips back and forth. Because the device is counterweighted, as the table tips, the clock hand turns. It was only really used by serious Spiritualists; it didn’t catch in pop culture.”

Spiritualist W.T. Braham developed this 1910 dial-plate planchette called the Telepathic Spirit Communicator. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

The first spirit-communication device to be patented was invented by German music professor Adolphus Theodore Wagner (no relation to opera composer Richard Wagner) and patented in London in 1854. After years of research, Hodge finally found down a period illustration of this “Psychograph,” which is similar to a draftsman’s pantograph.

“It’s got four crossbeams and four discs on each intersection,” Hodge says. “One of the arms is stabilized on the edge of the table, and the other end has a pointer on it, which goes over a little alphabet pad. Everyone puts their hands on the discs, and this crude mechanical crossbeam moves autonomously and points to the letters. That device had some very quick competition in Berlin with Daniel Hornung’s ‘Emanulector,’ which is more like Isaac Pease’s Spirit Telegraph Dial. It attaches to a table, the table tips, and a disc revolves.”

Brandon Hodge managed to track down a rare 1855 Spiritoscope made by Dr. Robert Hare, the oldest item in his collection. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

Even as early as the late 1840s, the world’s most famous chemist, Dr. Robert Hare, whom Hodge calls “the Neil deGrasse Tyson of his age” and who designed variations of the Bunsen burner, decided he would set about destroying Spiritualism with science.

“Dr. Robert Hare created a couple of tables that have these dials on them, blind-test devices,” Hodge says. “The medium would sit behind the table, the table would tip, and as it rolled back and forth, the device would turn and the scientist would record whether the medium, without being able to see the letters and numbers, could spell out a coherent sentence. Then, he got ahold of an Isaac Pease Spirit Telegraph Dial and liked the look of it. In his writings, he gave us the best descriptions of those devices because we don’t have a surviving one. He talked about going to a foundry and having them cast his modified versions of the Pease dial to create smaller test devices he could travel with. He called these ‘Spiritoscopes.’”

George F. Pearson’s 1900 Cablegraph. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

Hodge had the good fortune of managing to track down and acquire the only known surviving Dr. Hare Spiritoscope from 1855, the earliest spirit-communication device known to have survived to today.

“We were still in a period of Indian Wars and shuffling Native Americans off to reservations, yet it was popular to have a sagely Native American spirit guide.”

“Hare traveled around to different mediums performing these tests,” Hodge says. “He became convinced that these mediums were disproving his hypothesis that Spiritualism was fraudulent. So he totally flip-flopped, and published an illustrated book called, ‘Spiritualism: Scientifically Demonstrated.’ This would be the modern equivalent of Neil deGrasse Tyson going on a ‘Cosmos’ episode and saying, ‘I just ran all these tests, and Heaven’s for real.’ It created a huge national uproar. Hare got rejected from the scientific community, and the Spiritualists didn’t really like him because he set off to debunk them but then converted.”

Because of all the mediums being exposed, the 1870s has a distinct lack of patents for spirit-communication devices. But that started to change in the 1880s, as true believers were still looking for new ways to connect with the dead.

Hodge prefers Hudson Tuttle’s Psychograph from the 1880s to the Ouija board. (Via MysteriousPlanchette.com)

“Hudson Tuttle developed his ‘Psychograph’ in the 1880s, similar to Holmes & Co.’s ‘Alphabetic Planchette’ dial of 1868,” Hodge says. “Tuttle’s Psychograph was a square board with the letters and numbers and a dial set in the middle. Everyone puts their hands on the dial and it spins around and points to the letters and numbers. A Tuttle Psychograph is a beautiful instrument, a one-piece unit, and you don’t have this separate planchette with legs that can fall off. It works smoothly, and it’s accurate. But the Tuttle psychograph never really moves beyond Spiritualist circles. There are other dead-end devices like that, and mostly, they have what I consider a more efficient form than the Ouija board. But the Ouija just came along at the right time.”

“If you bothered the medium, maybe the spirit would come out and whack you in the head.”

The Ouija board became a hit right after it debuted in 1890, but it’s murky who came up with the idea of the “talking board,” a game board which requires a small ideomotor-driven planchette to point to its letters and numbers. Hodge said researchers have records of a family in 1876 engraving an alphabet on a table and rolling a dowel to point to letters and numbers. Other devout Spiritualists were using writing planchettes to point to letters and numbers in the 1870s. In 1886, the W.S. Reed Toy Company in Leominster, Massachusetts, sent President Grover Cleveland a talking board called “Witch Board” as a wedding present. “He actually responded back to the toy company thanking them for the divination device, and reminding them that he won’t be using it to disclose the past and foretell the future.”

After Bond and Kennard patented their invention in 1891, the W.S. Reed company produced the now-rare talking board “Espirito.” The Ouija Novelty Company might have threatened Reed with a lawsuit, because the company shortly ceased production of Espirito. The popularity of Ouija reduced the planchette to a smaller version of itself, a pointer accessory for the new talking board.

The Espirito talking boards, like this 1892 model, were produced for a brief period of time and, therefore, are especially rare now. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

Toy makers jumped on the talking-board bandwagon. In 1892, board-game maker Milton Bradley produced a talking board called “Genii: The Witches’ Fortune Teller,” which differentiated itself from the Ouija with its slide-rule functionality, but was strikingly similar to “Aura: The Psychic Talking Board.” A Spiritualist named George Pearson patented a beautiful new dial plate called the “Cablegraph” in 1900.

“Once talking boards come along in the 1890s, writing planchettes maintain the barest of fingerholds on the popular imagination up to the ’20s and ’30s, particularly in the U.K., but just as sort of a sideline,” Hodge says. “They would never again be the dominant spirit-communication device in popular imagination.”

Generally, mediums stayed away from devices that were popular with the general public. However, Leonora Piper, who became a medium in the mid-1880s, employed a planchette. Likewise, in the 1910s, Pearl Curran began to publish novels, poetry, and prose she said a spirit named Patience Worth delivered to her via Ouija. In 1917, Curran’s friend Emily Grant Hutchings published a novel called Jap Herron that she claimed was written by the late Mark Twain through her Ouija board.

The sheet music for 1920’s “Weegee Weegee Tell Me Do” shows lovers playing with a talking board. (From the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library at Duke University)

After the devastating losses of World War I, Ouija boards and mediums surged again in the late 1910s and 1920s. Again, what starts out as a serious interest in contacting people who died evolves into a titillating parlor game and an opportunity to flirt. In May 1, 1920, “The Saturday Evening Post” featured a Norman Rockwell cover showing a woman and man with their knees touching. “The Ouija’s on their lap, she’s looking up toward the sky, and he’s looking down and subtly pushing the planchette towards yes as if he’s just proposed,” Hodge says. That same year, the song “Weegee Weegee Tell Me Do” played with the same Ouija marriage-proposal theme.

While Spiritualism was flowering once again, the skepticism was also growing. A magician named William S. Marriott discovered a secret catalog from 1901 called Gambols With Ghosts: Mind Reading, Spiritualistic Effects, Mental and Psychical Phenomena and Horoscopy that was passed around among mediums. According to The Haunted Museum, the catalog offered ghost figures, fake ectoplasm, self-playing guitars, and self-writing slates. When investigating a medium who performed apportations in Germany, Marriott discovered he had stuffed a silk light shade with boiled prawns, and with a slight nudge, seafood would appear to fall from thin air.

Magician William S. Marriott ordered a bunch of fraudulent medium props from the “Gambols With Ghosts” catalog in the 1910s. At left, he poses with fake spirit hands. (CultofWeird.com) At right, he poses with ghost puppets. (Via The Haunted Museum)

Before his death in 1911, Ira Davenport revealed to escape artist Harry Houdini that he and his brother William never considered themselves Spiritualist mediums but magicians. They were skilled at contorting their limbs to get in and out of rope binds that supposedly held them in their manifestation cabinet.

In the 1920s, Houdini, who was adamant about the legitimacy of his own escapes, took up exposing Spiritualists and other magicians he considered fake or fraudulent. “Scientific American” magazine sponsored a contest that offered $2,500 to any medium who could prove true psychic gifts, and Houdini was on the panel of judges. One of Houdini’s biggest challengers was Boston medium Mina “Margery” Crandon, who was known for holding séances in the nude and excreting “ectoplasm” from her vagina. According to The Haunted Museum, Margery’s spirit guide, supposedly her late brother William, claimed Houdini was cheating by rigging his tests, and the judge panel was hung and unable to give her the prize.

“Houdini ravaged Spiritualism,” Hodge says. “He set up little ‘colleges’ in cities like in Chicago for cops to attend to learn how to bust up séances, and there was a concerted national effort to stamp out fraud. The Spiritualist believers never successfully cohesively banded together, because they were torn asunder by their own internal arguments about spirit materialization.”

This show poster from 1909 boasts Houdini’s new career as a ghostbuster. (Via WikiCommons)

Hodge says magician debunkers like Marriott, Houdini, and, later, Joseph Dunninger were motivated by a desire to protect the people from frauds who were exploiting their grief. “I don’t know that it was a fair assessment or that Houdini’s and Dunninger’s actions were fair. What was the service that the mediums were providing? Comfort and reassurance that the soul persists. If someone chooses to pay and buy a ticket to an event where a psychic tells them this, who am I to judge if that person received comfort and confirmation that their loved ones are watching over them? People tithe the church for that exact same confirmation. A Methodist preacher might tell us that at a funeral, ‘Your loved one is still here with you, and they watch over you. They love you, and God loves you.’ How is that so different?

“The idea was that the medium was supplying ectoplasm—believed to be a combination of energy and matter—from her body for the spirit to inhabit.”

“There were certainly fraudulent mediums who took undue advantage of some of their subjects,” he continues. “A medium attaches to a lonely widow and convinces her that her husband is pleading with her from the great beyond to sign over her inheritance to the medium in gratitude for establishing this communication? Yes, that’s terrible. Terrible, terrible, terrible. But on a more basic level, fraud is fraud. And I dare say with a small amount of research, we could probably find some Christian pastors who have indulged in similar activity. So there was some harm done. But I think it’s been unfairly and disproportionately levied upon Spiritualism and mediums as a whole.”

Tromp says that Victorian and Edwardian men found the spiritual and political authority women had as mediums incredibly threatening. “There are people who disagree with me about this, but I absolutely think the debunking was very gender-driven,” she says. “Most debunkers were very powerful men, and most of the mediums they exposed were young women. To me, they were asserting, ‘Get back in your place, little girl!’ I find some of the exposures to have a rape-like language about them. That doesn’t mean there weren’t mediums who engaged in charlatanism. But why would you grab a person physically in order to expose her when the alternative, of course, is just to lift the curtain in the cabinet or turn a light on. The debunkers, I think, were experiencing the thrill of power as well.”

Mina “Margery” Crandon excretes “ectoplasm” from her ear at a séance. (Via Mind-Energy.net)

Ultimately, these women who’d experienced so much celebrity and power had the rug pulled out from under them by debunkers and exposures. Most of them, like the Fox sisters, ended up impoverished.

“If you got access to all these things that you didn’t have access to in other parts of your life—like you got access to a voice and a spiritual authority—then when you’re outside the séance, how do you cope with giving that up?” Tromp says. “It must have been very, very hard. A lot of the famous mediums became alcoholics. Many people have said is, ‘Oh, you see, it’s because they were liars, and they were trying to cope with all the fraud.’ That’s one possible interpretation, of course. But how do you have power and respect and then leave the room and, with the same exact people, not have that anymore? Many of them ended up broken women.”

In the United States these days, “paranormal research” and ghost-hunting thrive under the umbrella of pseudo-science, but Spiritualism as religious practice is a shadow of its former self, with a few churches here and there. In today’s American culture, it’s widely believed that psychics who sell their services over the phone or at storefronts are clearly frauds, and anyone gullible enough to employ them deserves to be conned. On a rare occasion, a medium gains enough attention to land on TV—like John Edward, who has done readings on his shows, “Crossing Over,” which ran on the Sci-Fi Network from 1999 to 2004, and “John Edward Cross Country,” which has been on WE TV since 2006.

In the 1920s, the Wilder Manufacturing Company produced The Mitch Manitou talking board. (Photo courtesy Andrew Vespia Collection, via MysteriousPlanchette.com)

The most prominent remnant of the era of Spiritualism is the Ouija board, which now makes many people recoil in fear. Hodge says his collaborator Robert Murch traced the modern depictions of Ouija boards as demonic to the brief scene in 1973’s “The Exorcist,” where the little girl is talking to Captain Howdy on the board before she becomes possessed.

“This idea has rolled terribly forth into 2014,” Hodge says. “You’ve got people who might see any other horror movie but are refusing to see this ‘Ouija’ movie. I give talks at paranormal conventions all the time. Some people in the audience are more than happy to listen to electronic voice phenomenon or grab one of those little K-2 electromagnetic frequency meters, walk around in the dark, and ask the spirits if they’re there. But the concept of a cardboard board with letters and numbers printed on with the plastic planchette is opening a gate to hell and should not be trifled with.”

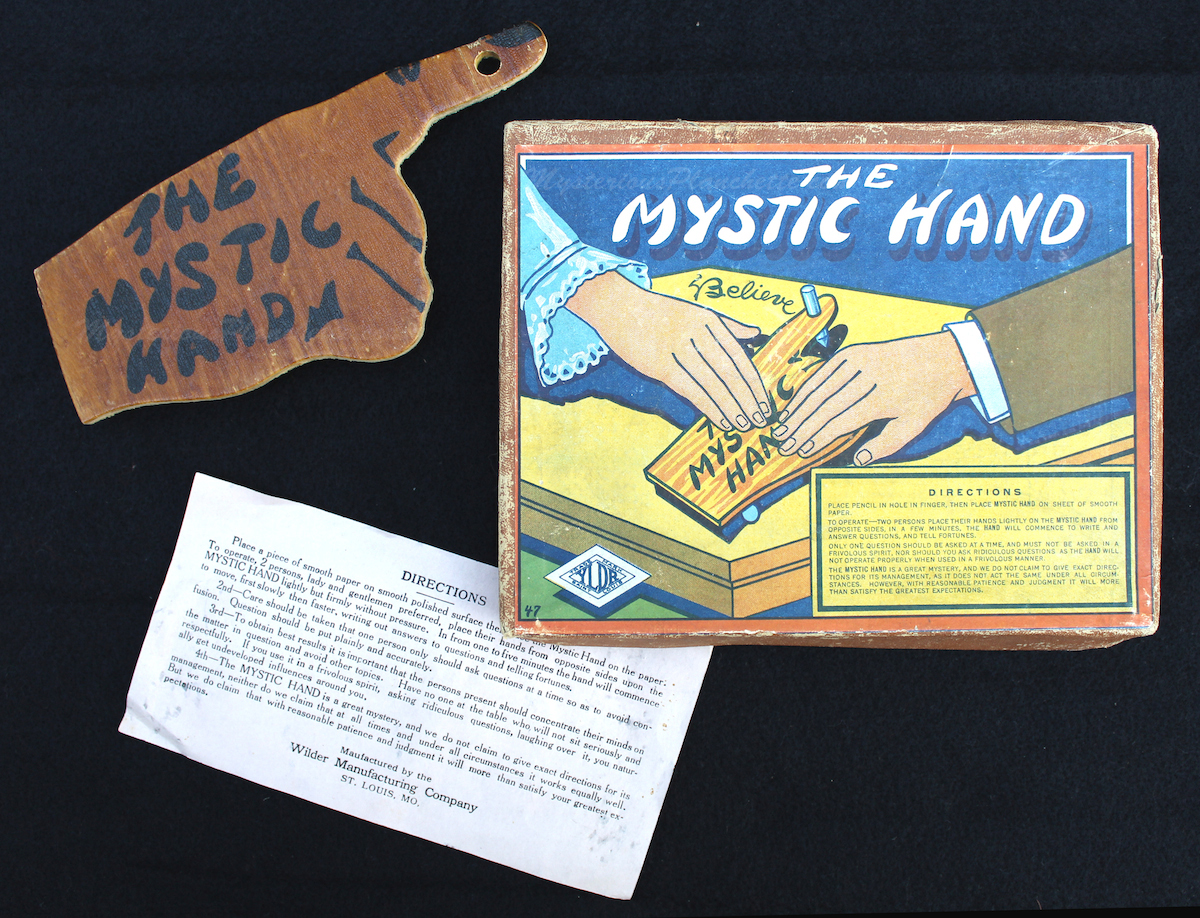

Wilder also made The Mystic Hand writing planchette in the 1920s. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

While people are excited by or terrified of Ouija boards, they’ll often pass by a writing planchette and have no idea what it is. The fact that plenty of spirit-communication devices like planchettes, spirit trumpets, and dial plates are languishing unknown in antiques shops is an indication of how the secrets and scandals of Spiritualism have been lost to time.

“I realized there were lots of Ouija collectors out there, but before I came along, no one had ever championed the planchette,” Hodge says. “When planchettes show up in online listings, they’re often listed as broken because they only have two wheels and they’re ‘missing’ their third wheel. Well, they’re not—that’s where the pencil goes. That’s an incredible source of frustration, knowing that those items are out there but the people who have them don’t know what they are. The Ouija board has all the sexiness, but the planchette has been relegated to the dustbin of history. ”

Selchow and Righter produced The Mystic of Mystics Planchette in the 1920s. (Courtesy of MysteriousPlanchette.com)

(For more information, check out Brandon Hodge’s site, MysteriousPlanchette.com, Robert Murch’s site on Ouija board manufacturer William Fuld, as well as Museum of Talking Boards and The Haunted Museum. To catch one of Jill Tracy’s “Musical Séance” shows follow her at her web site, or on Facebook or Twitter. For further reading, pick up Marlene Tromp’s “Altered States: Sex, Nation, Drugs, and Self-Transformation in Victorian Spiritualism”; Christine Ferguson’s Determined Spirits: Eugenics, Heredity and Racial Regeneration in Anglo-American Spiritualist Writing”; and Alex Owen’s “The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England.”)

Could Your Stuff Be Haunted? Ghostbusting the Creepiest Antiques

Could Your Stuff Be Haunted? Ghostbusting the Creepiest Antiques

Dark Art: Spectacular Illusions from the Golden Age of Magic

Dark Art: Spectacular Illusions from the Golden Age of Magic Could Your Stuff Be Haunted? Ghostbusting the Creepiest Antiques

Could Your Stuff Be Haunted? Ghostbusting the Creepiest Antiques Our Dad, the Water Witch of Wyoming

Our Dad, the Water Witch of Wyoming GamesFrom marbles and yo-yos to card games such as poker and modern multi-player…

GamesFrom marbles and yo-yos to card games such as poker and modern multi-player… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Arthur Conan Doyle was a believer in spiritualism and spirit photography. He and Houdini were friends, until Houdini went about disproving things that Conan Doyle held as true.

I was introduced to table tipping in 2011 and have had several impressive experiences and actually was able to do it at home this past Thanksgiving.

One glaring error that could have been avoided by referral to WikiPedia – The “Crookes Tube” had nothing to do with distillation, it was an early precursor to the X-Ray tube.

My question is were all vintage spirit trumpets aluminium and were any of them small

I understand that many devices were used as aids for automatic or spirit writing so would request anyone knowing about where these were pictured or described to please give me a link to the required material. Dr Anita Muhl is reported to have used such devices as arm supports, or slings or planchettes on her patients who provided information or material related to their problems through automatic writing as an approach to the unconscious. Thank you.

Small correction re Spiritism vs. Spiritualism. The article has reversed info. Spiritism, based on Kardec’s work, was far more direct than Spiritualism. Spiritists don’t even have churches: They attend meetings and donate all monies to charities. Spiritualism does have churches, though in far fewer numbers in the U.S. than the UK. Spiritist meetings are plentiful in Brazil, but that’s as much to do with the legendary medium Chico Xavier whose 400+ psychographed books raised millions for charity. He was even voted most important Brazilian of the century. We’d simply urge anyone skeptical about his particular brand of ‘spirit contact’ to explore his bio as well as his bibliography to make an assessment. (For infotainment at its best, we recommend the (English subtitled) film based on Chico’s book, ‘Nosso Lar’ – ‘Our Home’ in Portuguese. The English title is ‘Astral City: A Spiritual Journey’. It’s basically Brazil’s GWTW. :-)

Paz y luz, all. ♡☆♡☆⊙♡☆♡☆

Perhaps it’s inevitable that believers in just ‘some’ evidential mediums are labeled gullible. On the other hand, folks who have experienced NDEs and/or OBEs have peered into places we might not have believed otherwise. We certainly don’t wish an NDE on anyone, but wouldn’t take anything for the experience. #FamousLastWords