At the height of the live-magic era, seeing was believing. On a nightly basis, heads were severed and reattached, horses levitated from the stage, and bullets were caught in mid-air. To advertise these impossible feats, magicians at the turn of the 20th century commissioned vividly illustrated posters, emblazoned with exotic-sounding names and ominously scowling faces, daring you to doubt them. More than 100 years later, these posters still provoke an insatiable desire to see these illusions firsthand.

“How do you look at a poster of somebody being decapitated and not buy a ticket to see it performed live?”

Magicians of the period typically got their start in vaudeville, sandwiched between song-and-dance routines and stand-up comedians. But if an illusionist had enough charisma, he or she might strike out on their own, headlining a show of death-defying acts and sleights of hand that left crowds dumbfounded. Fans especially loved the darker side of magic, so the most successful magicians frequently toyed with life and death, evoking the power of some otherworldly being.

Top: A ghoulish Carrère poster, circa 1920. Above: A rare lithograph for Harry Thurston, Howard Thurston’s younger brother who had close ties to the mob-run underwold in Chicago, circa 1930. Images courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Today, we naturally think of Harry Houdini, but he wasn’t the only star of the magic world: Alexander, Thurston, Nicola, Hermann, Benevol, George, Dante, and Carter were all once-familiar names to millions of magic fans around the world. Though Houdini’s untimely death in 1926 made him a legend, it also ushered in the end of an era, as the rise of filmmaking pulled the rug out from under magic stage shows. Audiences wanted the thrill of a show that wasn’t live, whose magic lay in the fact that its actors were far away, brought to life by a trick of technology.

As someone who was raised in Los Angeles and works in television production, Zack Coutroulis is well-versed in the backstage tricks of the film and TV industries. But for Coutroulis, who shares his magic ephemera on Show & Tell, the golden age of magic holds a greater allure than the illusions of our digital present.

Having spent considerable time among magic-poster enthusiasts, Coutroulis is well-acquainted with the veil of mystery many keep over their collections, never admitting what they own or allowing these artworks to be shown publicly. “Some of these posters have never even been photographed before,” Coutroulis explains, “and they’re amazing. But poster collectors tend to keep to themselves. I’m one of the few people that actually enjoys sharing them.”

We recently spoke to Coutroulis about his favorite magic posters and the grand illusionists of the last century.

Collectors Weekly: How did you stumble into the world of magic posters?

Zack Coutroulis: It started at a very early age for me. In the third grade, I had to write a report. I forget exactly what the assignment was, but it was about people who changed the world, or historic, important people. Everybody wrote about presidents or our forefathers, but I did my report on Houdini. And I got an F.

I remember staying after school and asking my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Johnson, “Why did I get an F?” and she goes, “Because there’s no magician in the world that was ever of any importance.” I debated with her for nearly 20 minutes, and I think she wound up changing my grade. That’s how magic first intrigued me as a child.

A circa-1930 stone lithograph for a magician troupe called “The Fak Hongs.” Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

I got interested in posters through my parents, because when I was growing up, they had a lot of original circus posters. My father is a creative director in advertising, thus has the great eye for graphic design and posters. I inherited his genes and have the same passion for the graphically beautiful images on these posters. I grew up in a house with original circus posters, advertising posters, minstrel posters, and Buffalo Bill posters—all these original lithographs. My parents bought them for nothing before I was born, they’d go into an antiques shop and buy them for $20 or $50.

The problem with these stone lithographs is that photos don’t do the posters justice. I do the best job I can of photographing them, but you have to see the posters in person to truly appreciate their colors and the artist marks left from the lithographers who created them. They’re breathtaking. Most of these posters are more than 100 years old, but they still hold up today, if they’re taken care of.

Two highly dramatic posters depicting levitation and decapitation illusions by the infamous Kellar, circa 1894. Via wikipedia.org.

Collectors Weekly: What exactly is a stone lithograph?

Coutroulis: Stone lithography is a printing method that’s mostly lost today. Artists or lithographers would draw on these great, big slabs of limestone, and for every color of the poster, a separate stone had to be drawn. From these stones, they would hand-print the posters, or lithographs, using registration marks on the poster and moving it from stone to stone and color to color.

“These were advertising posters. The performers wanted to capitalize on the fears of the audience members.”

The sheet counts are basically a size measurement for the poster. For a half sheet, the measurements are roughly 21 by 28 inches. A one-sheet is 28 inches by 42 inches, and then it goes up from there. There are three-sheets, six-sheets, eight-sheets, and the measurements keep climbing. Some magicians even had 20-sheet posters, which is like billboard size.

Most people don’t realize that if you take two of the same poster and put them up next to each other, they’ll be different. No two stone lithographs are ever alike, since they were all done by hand. You look at the Carter “Cheats the Gallows” poster, which is the eight-sheet I posted on Show & Tell. That poster is 9 feet tall, and it’s got every color you can possibly imagine, and they’re so bright and vivid.

Part of the beauty of these posters is that they were printed in order to be displayed temporarily; they were never meant to be saved. The original posters are made of very thin paper, almost like newspaper material. You breathe on them wrong, and you’ll split them in half. The fact that these posters even exist, no matter what condition they’re in, is amazing.

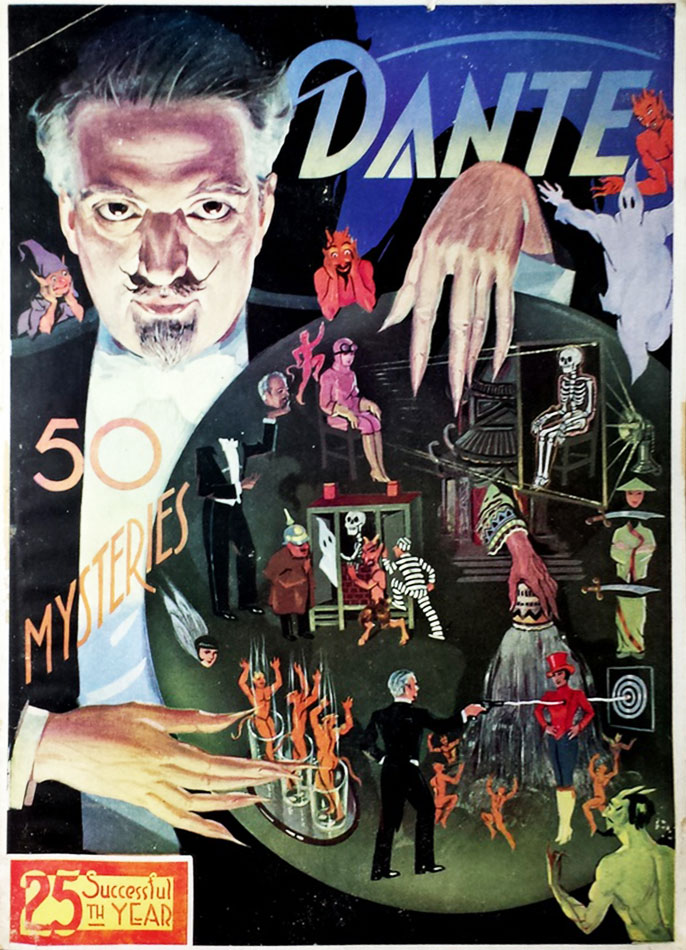

Dante’s ghoulish countenance watches over a series of vignettes depicting his various illusions on this program cover, circa 1930. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

You’re never going to be able to go back and see those magicians perform. For someone who loves magic, those days are gone. You can only live them through the posters. I look at these posters, and they take me to a place I’ve never been, but always wanted to be.

Collectors Weekly: Do you specialize in certain magicians or types of posters?

Coutroulis: For me, it always comes down to the image—a well-designed, striking image, or one that I fall in love with. That’s first and foremost, and it doesn’t matter what era a poster might be from. But most of what I collect is from what’s called the “golden age of magic,” which is basically the late 1800s to the early 1900s. These 50 years at the turn of the century represent the best posters you can find, at least in my opinion, graphically and subject-wise.

There are essentially two types of magic posters. There’s the portrait poster, which basically depicts a portrait of the magician. Those mostly came later once the magician was established, like Houdini, Kellar, or Thurston. The other type of the poster, my favorite, is the illusion poster. Those depict the actual illusions that audiences could expect to see once they came to the show.

Often, the illusions advertised were nearly impossible feats. How do you look at a poster of somebody being decapitated and not buy a ticket to see it performed live? To decapitate somebody and then reattach their head, that’s a brilliant illusion. One of the most amazing illusions depicted on a poster was Houdini’s Chinese Water-Torture Cell, an incredible death-defying illusion. You look at that poster and you’re like, “There’s no way!” He’s clearly risking his life.

Collectors Weekly: How did the water-torture illusion work exactly?

Coutroulis: I have to keep the magician’s code here, so I can’t tell you everything. Houdini was shackled by his legs, lifted up and placed inside the cell, completely submerged in the water. It was filled to the top with water, so when they lowered him into this torture cell, the water would overflow a little, which gave it a more dramatic visual. You know he’s in there and it’s airtight. Houdini would be handcuffed and his legs were attached to the top of the cell. And a curtain was drawn.

But don’t forget that Houdini, besides being an incredible showman, he was able to hold his breath for very long periods of time, so that helped. Every show, before he got into that cell, he would always say the same thing. “Now, when I go in the water, I want everybody in the audience to hold their breath as long as they can.” And they did, but of course, he held his breath even longer.

There were assistants placed on either side of the cell, with axes, ready to break it open should he panic and not be able to escape. Obviously, they wanted to save his life, but that added drama, too. So they would seal him in there and draw a curtain. But they couldn’t just let the audience sit there for four or five minutes; they’d get bored and leave. Instead, they would open the curtain a few times so you could see that Houdini was still submerged in the water tank trying to escape. At the end of the illusion, the curtain raised and he was standing on top of the torture cell free of cuffs. That’s probably my favorite illusion.

The other illusion that was pretty out there was the Bullet Catch. In fact, that’s how the magician Chung Ling Soo died. It was a death-defying illusion where people would load a rifle with marked bullets and fire at the magician, and the magician would literally catch the bullets in the air before they hit the body. And numerous magicians, including Soo, actually died attempting this trick, but when it was done well, that was an absolutely amazing illusion.

American-born William Ellsworth Robinson took the stage name Chung Ling Soo from a Chinese magician named Ching Ling Foo and maintained his image by using a fake interpreter in all public appearances. Robinson was accidentally killed when his bullet-catching act went awry in 1918. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Collectors Weekly: It seems like magicians were viewed very differently back then.

Despite his haunting posters, like this ad from 1935, Dante welcomed children at his performances. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Coutroulis: Today, David Copperfield is really the only magician most people know. I’ll be honest—I saw the Copperfield show not too long ago, and I was extremely disappointed. His show in Vegas at the MGM Grand was very light-hearted. His illusions do not live up to the standards. Here’s a man who has more money than God, so he can create and build any illusion, any show he wants. But he’s tired. He puts on two or three shows a day in Vegas. I was sitting in the front row, and I could tell that he was tired and bored. And if that’s the case, don’t do it. Your passion’s gone; your drive’s gone. Hang it up.

Copperfield is the last of the great illusionists, but you can’t compare him to magicians 100 years ago. Those magicians started in vaudeville alongside other stage performers, a few of whom were magicians. They would travel from town to town, and the biggest magicians had train cars full of equipment and illusions. Every time they came to a new city or town, they would print up new lithos and post them up to advertise the show. Then, just as quickly, the lithos were taken down or posted over by new acts that were coming the next week or the next month.

Back then, all these magicians were stealing each other’s tricks and always trying to outdo each other. Take sawing a woman in half, one of the oldest illusions in the book. It was first created, so they say, by a magician named P.T. Selbit. At the time, it was this amazing new illusion. Eventually, Dante attempted to improve it, and actually made it into a better illusion. All these magicians went to one another’s shows to make sure they weren’t being copied, but also to steal illusions. It was a cutthroat business.

Collectors Weekly: Did the best magicians develop their own unique illusions?

This Carter poster, circa 1926, focuses on the spiritual elements of his stage shows. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Coutroulis: Yeah, absolutely. If you were doing a grand illusion for the first time that no one had seen before, that was pretty amazing. By the time it got to the third magician or illusionist, the audience has already seen it, so it was less impressive. For example, Harry Houdini was an escape artist. He singlehandedly created that genre of magic, and he was the best at it. But eventually there were other magicians that dabbled in escape as well.

Magicians were always trying to outdo each other and build the next big illusion, but they didn’t always work. One example that’s still a great mystery in the magic world is the Indian Rope Trick, which was never revealed or proven. The performer would throw up a rope and it would stick in the air, straight up, and an assistant would climb to the top of the rope and disappear. For decades, magicians tried to see this illusion firsthand. They would go to India to try and find someone that could perform it, but everyone failed. It seemed like a myth. Thurston attempted the illusion in his show, but it never really took off.

Another attempt was the Vanishing Horse. Thurston called upon Dante, who was building his illusions at the time, and said, “Here’s the deal. We’re going raise a horse up from the stage and make it completely disappear.” They were building the illusion in their workshop, using trial and error, but when they went to lift the horse for the first time, one of the ropes broke. The horse came crashing down, and got excited and ran throughout the whole workshop, destroying everything, and almost killing them. It was insane. But eventually, they got it done. You can see the posters.

Dante started out in the world of magic by building illusions for Thurston, and he did such an incredible job that Thurston finally said, “I’m going to put you on the road as the Thurston number two.” He sent Dante around the world performing, and they shared the profits. But Dante grew into his own; he was huge.

Collectors Weekly: Was Dante his given name, or was it a stage name?

Coutroulis: It was a stage name. Almost every single magician has a different real name, except for the Thurston brothers. In fact, Howard Thurston was the person who gave Dante his name. Dante’s real name was Harry August Jansen, and before he was Dante, he performed as Jansen. There’s a few Jansen posters floating around, but they’re hard to come by.

These Von Arx and Brush posters, circa 1920, show the variety of supernatural references magic posters incorporated. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Collectors Weekly: Was it common to use more exotic or foreign-sounding names, like with the Indian Rope Trick?

Coutroulis: Well, these magicians were actually from all over the world. They didn’t only come from America, and everybody traveled to perform everywhere. Magicians would have posters written in Portuguese because they were down in South America or Japanese because they were in Asia, but the magicians themselves came from all over the world.

Benevol was Italian, but he was billed as a Mexican magician. I think he was performing in France and other parts of Europe. And many magicians with Asian names were American, like Chung Ling Soo. He was born in New York. Fak-Hong was another one; I think he was American, too. So they were also trying to be more appealing by billing themselves from these foreign countries and using foreign-sounding illusions.

Benevol’s portrait is surrounded by phantasmic imps in this lithograph from around 1920. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Collectors Weekly: Do the various names for “magician” mean different things?

Coutroulis: There are a lot of different words that fall under the title of magician, like conjurer or illusionist. In today’s world, an illusionist is somebody who performs “stage magic,” which means grand illusions that usually require the use of human assistants or animals, like tigers. Illusionists are people you’re going to see on a stage sawing somebody in half. Magicians typically do more close-up magic, or smaller illusions.

Then you also have what’s called a mentalist, or a medium as they used to call them. They supposedly have intuitive abilities like mind control, hypnotism, mental telepathy, or even performing very fast mathematical equations. Some successful magicians were solely known as mentalists, like Alexander.

Collectors Weekly: What’s behind all the nightmarish imagery of devils, skulls, and skeletons?

Coutroulis: Those are my favorite, with the imps and other creatures of the underworld. Dante put devils on posters, and Hermann actually portrayed himself as a devil on some of his posters. The skulls on the posters obviously represent spirits, or unexplained powers. In fact, Thurston has a poster that says, “Do the spirits come back?” A lot of these magicians made people believe that they could make contact with the dead.

Quite possibly the imps are whispering into the magician’s ear, and telling them how to make magic and perform these illusions. That’s one interpretation. Obviously, it’s also an association with the dark world. Anytime you start dealing with spirits and making contact with the unknown, you enter the dark world. Along with this come creatures of the underworld and things like that.

The magician-as-devil was a popular image, seen here on a Sorrows of Satan poster circa 1910. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

It’s also a bit of marketing: These were advertising posters. The performers wanted to capitalize on the fears of the audience members. Would they be able to see something that they only dreamt of? There’s really no single explanation of how this imagery got on the posters. But one thing’s for sure—one magician started doing it, and it worked, so they all did it.

But they still loved for kids to come. Dante would pull them up on stage at times, and use them as assistants. I have a handbill, a flyer for a Dante show from 1933 that says, “Six lucky boys and girls will receive free seats at the show.” And it continues to explain: “There is a word that is misspelled on this handbill. If you spot it, write it down on the back of this handbill and bring it to the show. The first six boys and girls to present this error at the door will receive free admission.”

This poster for the magician Kar-Mi, aka Joseph Hollingsworth, highlights the frightening intensity of his otherworldly shows, circa 1914. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Collectors Weekly: Were magicians able to support themselves financially?

Coutroulis: Yes and no. Howard Thurston, who was one of the most famous during his lifetime, died broke and in debt. He spent a lot of money. His younger brother, Harry, was a less-successful magician living in Chicago, and he had ties to the underworld. Harry ran some taboo, burlesque-type shows back in the day, and bankrolled Howard’s show many times when he was broke. Of course, Howard didn’t want to have anything to do with his brother’s line of work, but he still called upon him all the time and had Harry take care of his dirty work.

A lot of these magicians, like the Thurstons, were sleight-of-hand artists. They would con their way through things, and make illegitimate money, though they only did that to support their magical art. They would take that money and parlay it into their next show. In the beginning, when Howard traveled from town to town, if he didn’t have enough money to make it to the next town, he would pull a con.

On the other hand, Dante made a lot of money, but he was smart and retired comfortably. Houdini, Thurston, and Dante all made Hollywood movies, so they were quite successful. Whenever their main show wasn’t going on, they might also go back to vaudeville and perform in those shows to make extra money.

Yu Li San was the name given to the female medium that performed with a magician called “Profesor Alba,” during the 1950s. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Collectors Weekly: Have you come across any successful female magicians?

Coutroulis: Yeah, there were a lot of female magicians. One in particular jumps out at me, and her name was Ionia. She was popular during the golden age, and she specialized in grand illusions. Ionia dressed in Egyptian or Greek-style costumes, and made people appear and disappear. Her posters are phenomenal, very mythical, and I haven’t come across many of them. They’re extremely scarce and very rare—I think she only made around 20 posters.

Ionia was one of the few female-magician headliners, and she often represented herself with mythical symbols.

Many headlining magicians also had females in their acts. Thurston’s daughter, Jane, was a part of the show. Dante’s daughters were part of his show. But most of the women weren’t headliners. Even today when we say “top billing,” we mean the placement of a person’s name on a poster or broadside. Houdini’s name would be on top when he was the star. But when he wasn’t, he was down at the bottom.

Collectors Weekly: Do you have a single favorite poster?

Coutroulis: If a fire broke out, the first poster I would grab before I ran out the door would be the Thurston devil poster, his panel poster for the Wonder Show of the Universe. It’s roughly from 1914, and this poster doesn’t show the magician at all. It shows the devil, imps, and all these creatures of the underworld. It is the darkest, most mysterious, most sinister magic poster I have in my collection, and it’s the first poster that I ever wanted. The reds just pop; it’s so vibrant. It draws you in, and you have no idea what you’re about to see, but you know you’re in for a great show.

Collectors Weekly: Did these magicians ever reveal their tricks, or get publicly debunked?

Coutroulis: No, magicians don’t give away tricks. Of course, there was a time in the ’20s, when Houdini went on a mission to debunk psychics and mediums. He had a lot of experience with illusions, and he wanted to expose all the frauds, the ones who successfully fooled scientists and regular people. Houdini offered a cash prize to any medium who could successfully demonstrate their supernatural abilities. He tested tons of them, and he always figured out how they pulled the wool over everybody’s eyes, and debunked them all. As a result, the cash prize was never collected. Nobody could prove him wrong.

Before Houdini died, he made a promise to his wife Bess that when he was dead, if it was possible to reach into the beyond and make contact with the spirits, he would be the one to do it. I don’t know the exact deal they had, but there were secret words and things that would offer proof. And it’s been documented that to this day, they were never able to contact Houdini. He died on Halloween night, and for years after his death, people held séances on Halloween to try and reach his spirit.

Collectors Weekly: I grew up in Austin, Texas, and in the old Paramount theater there’s a hole in the ceiling from a Houdini performance in the 1910s. Supposedly, the lights went out, and when they came up again, there was a lion hanging from a cage over the audience.

Coutroulis: One of the great things about Houdini was his incredible showmanship. He offered public challenges where would lock himself up or tie himself upside down in a straitjacket in New York City in front of thousands and thousands of spectators. How do you top that? He wanted you to love his shows. Word of mouth was very important.

A broadside from 1877 for De La Mano, the magician that mysteriously disappeared. Courtesy Zack Coutroulis.

Collectors Weekly: What happened to De La Mano, the magician who disappeared?

Coutroulis: I have to start by saying this is undocumented, but as the story goes, De La Mano was last known to be investigating some psychic occurrences in Waterloo, New York. I think De La Mano was Austrian, and he toured in Europe. So he was on this farm, and I think it was 1882, and there was a thunderstorm. De La Mano was locked in his room and literally vanished from the face of the earth. No one ever saw him again. And gone with him was his entire show, his illusions, packed up somewhere, forgotten either in a warehouse or barn, but they never surfaced.

His broadsides and advertising were actually discovered much later by another magician named Peter Monticup. Peter found all of these broadsides tightly wrapped up in the original receipt from the printer dated 1887. I don’t know how many there were, but they were in pristine condition preserved in a trunk up in the rafters of this barn, and that’s how they got out. But it’s a mesmerizing story. De La Mano just vanished. Who knows if that’s truth or not?

Collectors Weekly: Why did the golden age of magic end when it did?

Coutroulis: Movies killed it. All of these vaudeville theaters became movie houses. When film came in, people wanted to watch movies, talkies, even silent films. vaudeville absolutely failed. It happened toward the end of Thurston’s career. He was getting fewer and fewer bookings due to movies. It’s the endless change in the world. Scripted television to unscripted television. Studio pictures to independent pictures. Change is inevitable and it happens all over.

(See Zack Coutroulis’s full collection on Show & Tell)

Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us

Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us

The Magician Who Astounded the World by Conjuring Spirits and Talking with Mummies

The Magician Who Astounded the World by Conjuring Spirits and Talking with Mummies Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us

Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us Ghosts in the Machines: The Devices and Daring Mediums That Spoke for the Dead

Ghosts in the Machines: The Devices and Daring Mediums That Spoke for the Dead Magic Posters and EphemeraThe Golden Age of Magic (1875-1930) generated thousands of colorful posters…

Magic Posters and EphemeraThe Golden Age of Magic (1875-1930) generated thousands of colorful posters… Posters and PrintsPosters and prints enjoy a number of obvious similarities. For example, bot…

Posters and PrintsPosters and prints enjoy a number of obvious similarities. For example, bot… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Such awesome stuff! Ionia’s poster is so pretty…

Funny how the illuminati owl appears in about half of the prints.

Lovely posters. Carter had four different 8-sheets, and one 16-sheet. They were awesome. You can see a lot of Carter’s stuff in the movie “Alabama’s Ghost—if you can find it.

The posters are stunning and the information on the stone lithograph process was very educational. Even in the oldest posters, the color is so rich. I regularly see a local magician perform with Esther’s Follies here in Austin; his illusions on a small stage are reminiscent of what the past performances of the greats must have been like. Well done, Mr. Oatman-Stanford!!!

I need to know more about de la Mano! That sounds like a fascinating story.

I did magic as a child, charging a dollar a minute. I still have all that stuff… but no old posters! I got into Radio and started collecting radios and microphones! Thank You for sharing all these collectible magic posters and all the fascinating history!

My husband has a picture of an illusionist in his family from the early 1900s. His name was Roscoe Emerson or Emerson the great and he lived in LA and in Las Vegas. We can’t find any info on him. I think I found his death certificate from the early 3os from a car accident in Ky. He was listed as an actor. Any info. would be appreciated. Thanks.