When NASA’s New Horizon spacecraft flew past Pluto and its moons recently, after journeying more than three billion miles over the course of nine-and-a-half years, much was made of the former planet’s craterless surface. The absence of craters indicates that Pluto is geologically active, which means that in this respect, if no other, Pluto is more like Earth than our pockmarked moon.

Perhaps Donald A. Wollheim had an inkling of Earth’s similarity to Pluto way back in 1959 when he wrote “The Secret of the Ninth Planet.” To be sure, the sci-fi author and publisher got a whole lot of things wrong—“Plutonians” are not “vaguely like men and vaguely like spiders,” primarily because there are no such things as Plutonians, and Pluto is actually smaller than our moon, which means its gravity would not feel similar to Earth’s, as described in the excerpt below. Regardless, Wollheim imagined his characters would feel more at home on Pluto than on any other planet they visit throughout the course of his young-adult novel, as Burl Denning (the story’s teenage hero), co-pilot Russell Clyde, and explorer Roy Haines discuss shortly after landing:

From “The Secret of the Ninth Planet,” by Donald A. Wollheim

Pluto was a vast hemisphere, half lighted in the faint, dim glow of the tiny Sun, half in the total darkness of outer space. Here and there wound a silent, frozen river of glistening white. They passed over a gulf of some frigid sea of liquid gases, from which islands of subzero rock projected, and moved inland over a continent of lifeless grays and blacks. Haines gently drew the ship lower and lower, and at last the rocket plane bumped to the ground.

It rolled a few yards and stopped. The three men crowded to the door, tightened their face plates, and forced open the exit. There was a rush of air as the ship exhausted its atmosphere. Then, one by one, they stepped onto the bleak surface of the Sun’s farthest planet.

“I feel peculiar,” whispered Burl. “This planet reminds me of something.”

“I have the feeling I’ve been here before,” Russ said slowly.

Burl felt an odd chill. “Yes, that’s it!”

Haines grumbled. “I know what you mean. I can make a guess. We’ve never really been the right weight since we left Earth. Even under acceleration there were differences one way or the other. But I feel now exactly as I did on Earth. That’s what gives you the odd sensation of return.”

The two younger men realized Haines was right. For the first time since they had left their home world, they were on a planet whose gravity was normal to them. It felt good and yet it felt—in these fearful surroundings—disconcerting.

Above them was the familiar black, unyielding sky of outer space. No breath of air moved. Yet somehow the scene resembled Earth. “It’s like a black-and-white photo of a Terrestrial landscape,” said Burl.

There was a field, some hills, a tiny frozen creek and the dark shapes of rounded mountains in the distance. All without color except for the cold, faint glow of the star that was the Sun.

A thin layer of cosmic dust lay over the surface, such as would be found on any airless world. Russ scooped beneath it and came up with a hard chip.

He squeezed it between his gauntleted fingers. It cracked and broke into powder. He whistled softly. “You know what this feels and looks like?” he said as they came close to the frozen creek on the little hillside. “It feels like dirt—common, Earthly dirt. Like soil. And you know what … I can already tell you one of Pluto’s secrets.”

They stopped at the creek. It was a layer of frozen crystalline gases. Haines pushed the alpenstock he was carrying into it and scraped away the gas crystals. “I think I can guess,” he said, “and I’ll bet there is ice under this gas.”

“Pluto was once a warm world with a thick atmosphere,” said Russ. “Notice the rounded hills and the worn away peaks of the mountains. Those are old mountains—weather-beaten. This hill is round—weather-beaten. This creek, those rivers of frozen gas—they follow beds that could only be made by real rivers of warm water. The soil that lies beneath this dust—it could only happen on a world that knew night and day, warmth and light, and rain and wind. Pluto was once a living world, a place we’d have called homelike.”

(You can read the rest of “The Secret of the Ninth Planet” at Project Gutenberg.)

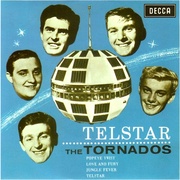

The Otherworldly Sounds of the Clavioline, From Musical Saw to Wailing Cat

The Otherworldly Sounds of the Clavioline, From Musical Saw to Wailing Cat

Laika and Her Comrades: The Soviet Space Dogs Who Took Giant Leaps for Mankind

Laika and Her Comrades: The Soviet Space Dogs Who Took Giant Leaps for Mankind The Otherworldly Sounds of the Clavioline, From Musical Saw to Wailing Cat

The Otherworldly Sounds of the Clavioline, From Musical Saw to Wailing Cat Women Who Conquered the Comics World

Women Who Conquered the Comics World Science Fiction BooksFor book collectors, vintage science-fiction titles hold a special appeal. …

Science Fiction BooksFor book collectors, vintage science-fiction titles hold a special appeal. … BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of …

BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.