When kindly old grandparents beckon their fresh-faced grandchildren into their rock-poster-lined man caves and she sheds, to vape sweet kush and wax nostalgic about the San Francisco music scene of the 1960s, their rambling recollections are often accompanied by the sounds of “Cheap Thrills” or “Aoxomoxoa”—cranked to 11.

“When you are painting with light, if people aren’t there, nobody sees it.”

Getting high with grandma and grandpa while listening to Big Brother and the Holding Company or the Grateful Dead is actually a fairly good way for curious Millennials to learn about this watershed era of the late 20th century, but loud music and recreational drugs were only part of the story. Just as important, if not more so, were the light shows that accompanied and responded to the sounds. Indeed, for the seriously stoned, the pulsating colors produced by light-show outfits with names like Heavy Water, Little Princess 109, and North American Ibis Alchemical Company were often the main event.

If you never saw one, a San Francisco light show was an immersive ocular experience for audiences and musicians alike. Amid these real-time paintings built from layer upon layer of ephemeral light, performers pushed their instruments to the breaking point, while audiences danced until they dropped. Without the light shows, San Francisco’s fabled music halls, where everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Eric Clapton held court, would have resembled just so many more run-down auditoriums and crumbling former ice rinks. In fact, that’s basically what the Fillmore and Winterland, two of the city’s most famous music venues, were. When illuminated by a light show, though, these decrepit dives were magically transformed into glorious temples of psychedelic iniquity.

Top: A Bill Ham light painting from a recent studio session. Above: Bill Ham next to a Herb Greene photograph of the residents of Pine Street in 1966. The group—which includes members of Big Brother and the Holding Company, The Charlatans, and The Family Dog—are standing in the vacant lot between 2111 and 2115 Pine Street. (Photos by Emi Ito)

For a good part of 1966, the most important year of the psychedelic sixties, despite the hype about 1967 and the Summer of Love, Bill Ham ran the light shows at the Avalon Ballroom, a former dance academy on the corner of Sutter Street and Van Ness Avenue. The Avalon was arguably the city’s darkest dive, which is not a swipe at its character. Rather, when a band took the stage at the Avalon, its members performed in the dark, lit only by Ham’s arsenal of overhead projectors, which were aimed at musicians, the walls behind them, and the kids on the dance floor. Thanks to the Avalon’s lack of stage lights and spots, the place became one enormous, undulating painting.

That was half a century ago. These days, Ham, now in his mid-80s, often paints with actual pigment on traditional materials such as stretched canvas and archival paper. In 2013, a film of Ham’s light paintings was projected onto an old church in Italy as a part of an exhibition of screenprints by Chuck Sperry (see video at the end of this article). Then, in 2014, Ham released a DVD of his light paintings, giving those who never saw his work at the Avalon a taste of what it looked like—San Francisco’s light shows were poorly documented—if not how it felt to be in the midst of one.

Recently, over the course of several mornings and afternoons, I sat down with Ham to learn about his arrival in San Francisco at the tail end of the Beat era, how he came to be the light-show guy at the Avalon, and his adventures with light in Europe during the early 1970s.

A recent painting on paper by Bill Ham. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: Why did you move from Houston to San Francisco in 1959?

Ham: I had a bachelor of fine arts degree from the University of Houston and had recently finished my service in the military. I was living in Houston, but knew I wanted to be on one of the coasts. New York City and Los Angeles weren’t for me, so I moved to San Francisco and took some classes at the Academy of Art, paid for by the G.I. Bill. That was my introduction to becoming a painter, which is what I wanted to be.

Collectors Weekly: How’d that work out?

Ham: Well, I only attended the Academy of Art for a couple of semesters, then I went north and worked in a sawmill for six months, after which I did a little traveling. By 1960, though, I was back in San Francisco ready to try to be an artist again. I still didn’t have much money, and oil paints were expensive, so I was making art in all kinds of media. I was doing some sculptural things, assemblages made out of scrap wood that I found on construction sites around town. I had a whole pile of wood, some of which I would burn to make it black. I also worked with plaster because you could buy a lot of it cheap—all you needed to add was water. So I was making different types of relief art using scraps of wood and other materials. It was a lot of experimenting.

The Soto Zen Mission on Bush Street in 1962. Students at the Zen center were some of the first people to see Bill Ham’s light shows. (Via cuke.com)

Collectors Weekly: Where did you live?

Ham: Toward the end of 1960, I moved into a three-story building at 2111 Pine Street. It was around eight to ten bedrooms, plus some common areas, and I was one of the first occupants after the new landlord, Peter Blasko, bought it. Bob Cohen, one of the future partners in Family Dog Productions, which promoted dance concerts at the Avalon Ballroom, rented a room shortly after I did. He arrived on a BMW motorcycle, which he had ridden from New York. Bob and I became pretty good friends during that time.

The building on Pine Street was located between Pacific Heights and Japantown near the Fillmore district, which had become the Harlem of the West during World War II. Fillmore Street was still a pretty busy place in 1960, with quite a few black music clubs. Nearby, on Bush Street, was a Zen center run by Reverend Suzuki. Some of the people who wanted to learn how to be Zen Buddhists also lived in the neighborhood, so it was a real mix of folks.

One day, before the young couple who had been managing the building decided to move to New York, the landlord came by to see if someone else would agree to be the building’s manager. Bob was the only one who answered his door, so he became the new manager. The job was basically to collect $30 or $35 from the residents, depending on which room it was, but Bob felt like it was too much pressure, so he passed it on to me and I became the manager. By then, the house had filled up. Usually if one person was renting a room, two people were living in it. There were also a lot of overnight guests. It was a very active place.

In the early 1960s, the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco, with its jazz clubs, poets (seen here in 1965 in front of City Lights Bookstore), and bars, was a regular place to hang out for Bill Ham and his Pine Street friends. (Via sfaq.us)

Collectors Weekly: I read in a book on San Francisco’s musical history that you “filled the premises with every woebegone miscreant” you could find. True?

Ham: I read that, too. I filled it with artists and musicians and creative people, so I’m not sure what that writer was talking about. We were particularly interested in the jazz and art scene across town in North Beach. The city bus didn’t quite get you there, so it was many a night that those of us who lived at 2111 Pine would troop back and forth to North Beach. We’d hear some music, have a few beers, and then walk back to Pine Street. On the way home, we often stopped at a place in Chinatown, where you could get a pork bun for a nickel; it might have been a dime. It was a lot of walking, back and forth. That was kind of the scene in the early ’60s.

When I got there, Peter Blasko owned 2111 Pine, the vacant lot next to it, and the two-story apartment building next door to that at 2115. Unlike 2111, which was more like a boarding house, the building on the other side of the vacant lot had two flats plus a garage and basement, with a crude, little apartment in the back of that. At some point, I moved out of 2111 and fixed up that basement apartment just enough to make it livable for me and my German shepherd, Odin. It was small, so in order to give us both a little extra space, I built a fence on the vacant lot, made out of about 20 doors salvaged from all the Victorians in the area that were being torn down. That way, I could leave the basement door open for Odin so he could escape the confines of our studio every once in a while. Sometime thereafter, a new landlord bought all of Blasko’s properties, plus anything else in the neighborhood he could get his hands on, including another rooming house a few blocks away at 1836 Pine Street. I managed that building, too.

As a light artist, Bill Ham was influenced by the work of Elias Romero. These stills are from a film Romero made in 1968 called “Stepping Stones.”

Collectors Weekly: Was the basement the site of your first light shows?

Ham: Yes, but they were more like experiments in painting with projected imagery; we didn’t call them “shows” yet. By then, it was 1964, and an artist named Elias Romero, who had been making light art with an overhead projector at an old church on Capp Street in the Mission District, was invited by playwright and director Lee Breuer to create light projections for a play call “The Run” at the San Francisco Tape Music Center. Romero’s projections were somewhat abstract, kind of landscape-ish. I made a sculpture for “The Run,” sort of a full-size wolf-dog, so we got to know each other while working on the play.

After the play, Elias moved into a house on Pine Street across from the basement studio where I lived. We would get together every so often for coffee, maybe smoke a joint, and visit. One day we were talking about how he wasn’t really set up to do anything with his overhead projector since he was living in an upstairs flat. Very generously, he lent me his overhead projector to take across the street, and that’s when I began experimenting. The garage portion of the basement became my first light-show studio.

“I didn’t tell the musicians how to play, and they didn’t tell me how to do the light show.”

There was no precedent for making art with an overhead projector that I was aware of, other than what Elias was doing. Elias worked in a controlled, minimal, almost poetic manner. For whatever reasons, I had assumed that I should fill up the whole projected image with color and movement. It was a lot of trial and error on my part to develop my own approach. I wanted my work to be totally spontaneous. I didn’t want to repeat myself—first do this, then do that, then do something else every time. I still don’t work that way.

With the help of Bob Cohen, who had been an electrician in New York, I put together a homemade sound system from parts I had torn out of an old television console, including its record player. Elias had an LP of “Carmina Burana,” so for our first and only collaboration, we played the record and took turns on the overhead projector.

Though light shows are mostly associated with rock, this classical record was one of the first pieces of music Bill Ham worked with.

I also experimented with a musician named Christopher Tree, who created what he called “Spontaneous Sound” with Elias during the Sunday night sessions at the Capp Street church. Christopher happened to be living upstairs from me, and his instruments at the time included an old timpani drum, several snare drums, gongs, bells, cymbals, and so forth. We would get together for sessions several times a week. I don’t think he ever worked with another visual artist after our brief period of collaboration, and today, he’s a one-man band, performing on the equivalent of a gamelan orchestra.

Once I began using the overhead projector as my painting tool—my brush, so to speak—an artist named Bob Fine, who had also moved into our little group of houses on Pine Street, began assisting me. He would continue to do so throughout the Avalon days, and beyond.

In a way, it wasn’t about creating light shows as much as it was coming up with a whole new approach to painting. Typically, an artist paints something in a studio, waits for it to dry, and then, when he’s got a bunch of paintings, invites people to his studio or a gallery for a show. When you are painting with light, if people aren’t there, nobody sees it. It was present-tense art, in which composition, execution, and observation were simultaneous. That changed the relationships between the painter, the painting, and the viewer.

A few of the people who lived in the Pine Street neighborhood understood that, and before long, they started showing up. It was like, Bill’s doing the light-show thing tonight, wanna go? It was just whoever wanted to show up. A couple of monks from the Zen center even came by one night, since it was only two blocks away. Eventually, Reverend Suzuki himself stopped in, but that was later.

In recent years, Bill Ham has been passing his light-show techniques on to a new generation. Here he instructs Kaishi Ito on the finer points of working with liquids in glass bowls on overhead projectors. (Photo by Emi Ito)

Collectors Weekly: Can you describe the techniques you were using at that time?

Ham: It started with the overhead projectors, which had been designed for lectures and presentations, so that lecturers could show their audiences diagrams, text, and other information as they spoke. Overhead projectors were used mostly in educational settings, for corporate meetings, that sort of thing. We repurposed them.

The main medium of the overhead projector had been the transparency. The light source below the projector’s flat surface, which is actually a Fresnel lens, would beam the image or words on the transparency onto a mirror above, which, in turn, aimed that image through a focusing lens and onto a screen or wall. Transparencies are dry, but we were projecting liquids, so the first things we needed to do were to protect the lens with a clear sheet of glass and then contain the liquids.

Early on, Elias had discovered that clock crystals—the clear pieces of glass that protect a clock’s hands and other moving parts—made good bowls for light-show liquids. They came in all shapes and sizes. Those that were deeply concave held more liquid. Others were flatter, which allowed you to do different things to the liquids. Some crystals with round bottoms could actually be spun in circles on the projector’s flat surface. And then, by setting one bowl on top of another, you could stack them up, several at a time, to produce even more effects, liquid- and color-wise.

Whatever the effect, the overhead projector was the only tool a light-show artist could use that let him actively direct the form and composition of the projection. Slide and film projectors were also used in light shows, but only the overhead projector allowed the artist to work directly with his liquid materials in a way that was truly spontaneous.

Collectors Weekly: What sorts of liquids are we talking about?

Ham: I could buy pretty much everything I needed at any grocery store—cooking oil, alcohol, and Windex—plus water from the tap. Each liquid had a different property and produced a different effect. Most of my colors were made from common food coloring, but food coloring doesn’t mix very well with itself—if you put a lot of blue and red into a bowl of liquid, pretty soon you’re working with something that’s not really a color anymore. So, the way to keep your blues blue, your reds red, and your yellows yellow is to have each one in a different dish. By putting the different oils and mixtures you’re using in different dishes, you can blend the colors together on the wall as light, creating a whole variety of effects.

Collectors Weekly: And these light experiments led to your gig at the Avalon?

Ham: Not yet. It was still 1964, and the Avalon didn’t happen until ’66. At some point, Bob Cohen met a guy named Chandler Laughlin at a bar in North Beach. Chandler worked with another guy named Mark Unobsky, who had just bought the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Nevada. Unobsky had big plans for the Red Dog. He had hired a French-trained chef and had an idea for music and some kind of light show, based on a rear-projection light sculpture he’d seen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Bob told Chandler that I should be his light-show guy, and he invited us to Virginia City to see the Red Dog, meet Mark, and figure out what to do next.

So we got some gas money from Chandler and made plans to drive to Virginia City in Bob’s VW bus. Then, two or three days before we were going to leave, Phil Hammond entered the picture. Phil also lived at 2111 Pine Street and was the manager of a band called The Charlatans. By then, word of what we were up to had gotten out—that there was a place in Virginia City that maybe needed some musicians—so Phil asked if he could go with us to pitch his band. He even offered to drive us in his car, which sounded more comfortable than Bob’s VW, so away we went.

The next day we met Mark, who described the light sculpture he’d seen in New York. From the beginning, it was understood that Mark didn’t expect somebody to actually be at the Red Dog every night to operate the device. Mark assumed it would be automated. So Bob and I went down to an abandoned train station in Virginia City, pulled out a sketchpad, and tried to figure out something that would satisfy Mark’s vague description, and what it might cost.

The Charlatans’ shows at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Nevada, during the summer of 1965 are widely considered the first psychedelic rock concerts. Bill Ham and Bob Cohen created an automated light panel that produced colorful effects for these shows. (Poster by George Hunter and Michael Ferguson. Image via Bill Ham Lights)

Bob was so excited—he had repaired his BMW motorcycle by reading a manual, so he figured he could engineer anything if he had a plan to work from. The plan we came up with was to build a kind of ever-changing, projecting, three-mirrored kaleidoscope. Mark agreed to pay us $1,500, with $750 in cash up front, so we headed back to the city. Bob and I were now partners.

Meanwhile, Bob had bought an electrical device like one he’d seen advertised in “Playboy” magazine—I think it was called a Color Translator. It had three electrical channels, each powering a different colored bulb, providing a rather limited visual thrill. But there was one other very cool thing about the device: Its channels responded to sound in three frequencies—low, medium, and high—which controlled the three lights.

The purchase consumed a good chunk of our money, and then Bob found out it wouldn’t drive all the motors we were going to use in our kaleidoscope, so it didn’t even suit the purpose we’d dreamed up. But I began to experiment with the Color Translator, which led to the idea of using it to light something from behind. As an experiment, I took some white paper and a few light bulbs, then cut out some shapes and put them between the paper and the bulbs. The shapes’ shadows showed up on the paper—that was the principle behind what became our light panel for the Red Dog. Eventually, a woodworker named Kurt Banks made two cabinets for us, each about the size of a sheet of plywood, with a piece of frosted Plexiglas in the front. We only ended up using one of the cabinets, though.

The Family Dog grew out of The Charlatans shows at the Red Dog Saloon. In 1965, The Family Dog produced three concerts at Longshoremen’s Hall. (Poster by Ami Magill and Alton Kelley, via Psychedelic Art Exchange)

Next, I built three mobiles that were turned by electric motors. The mobiles were basically coat hangers that were bent and tied together. Attached to them were red, blue, and green gels that I cut into different shapes. There were a few other things on the mobiles, like those glass teardrops that hang on cheap chandeliers, but mostly they were coat hangers and gels. The mobiles were suspended in the cabinet behind the Plexiglass, and Bob mounted the lights to the cabinet’s back wall—it was pretty close quarters in there. Since the mobiles were constantly in motion and the channels were being controlled by high, low, or medium sound frequencies, the colored shapes didn’t stay in one area of the panel for very long.

In addition, Bob had found a mixer at a surplus store, and he set it up so that every 20 minutes or so, the mixer varied the output of the channels in the Color Translator, which varied which spots were responding to which sound frequencies. So it wasn’t just the front of the panel turning different colors—the shapes were changing, too, which made it much more interesting because repetitions were rare. If you had to do a mathematical estimate of how many different combinations there were, you’d probably have a million or two. Bob was very much in charge of the fairly basic electrical connections that made it all possible.

When Captain Beefheart played the Avalon, he hung out with Ham between his sets learn how the light show was created. (Poster by Stanley Mouse, via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: The Charlatans played two weeks at the Red Dog in what became known as the first psychedelic rock concerts, but you’re telling me the light shows at those concerts were produced by a machine?

Ham: Yes. The light panel ran itself. Before we strapped it onto the roof of a VW bus that Bob had helped me rebuild, which we drove to Virginia City, we debuted it across the street from the Museum of Art in San Francisco. This was before the museum moved and became SFMOMA. Coincidentally, we had finished the panel just as the museum’s annual show of local artists was opening. Naturally, we hadn’t been invited to that, so we rented a 14-foot moving truck, lined the inside of it with black felt, and put the light panel as close to the cab as we could. We had plugged the Color Translator into a radio whose speaker had been disconnected, so when people who were walking by looked into the back of the truck, they didn’t know what was making the lights and shapes change. For them, it just happened. That was our only opportunity to show it before we delivered it to the Red Dog.

By the way, I don’t know what happened to the light panel at the Red Dog, but I still have the extra cabinet. At one point, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame called me about that, but when I told them I would need a little money to fix it up, the conversation ended.

Collectors Weekly: What happened after the Red Dog shows?

Ham: After Red Dog, in the summer of 1965, everybody came back to San Francisco and tried to figure out what to do next. George Hunter of The Charlatans moved into the Pine Street flat above my garage, but, by this time, I had the keys to four houses. One of them, 1836 Pine Street, was available, and that eventually became the Dog House, where the Family Dog collective, which ran the Avalon, got started.

In Virginia City, during the Charlatans’ run, everybody had a job to do. Now that everyone was back in San Francisco, the perennial goal was to pay the rent. So in the fall of 1965, some of the people who had helped with the Red Dog shows—Luria Castell, Ellen Harman, Alton Kelley, and Jack Towle—rented Longshoremen’s Hall in San Francisco over three weekends to re-create the Red Dog experience and hopefully make some money for rent.

Since Bob Cohen had been the soundman at Red Dog, that became his job for the Longshoremen’s show. Kelley, who co-designed the handbill for the first Longshoremen’s concert, invited me to do a light show. By then, I had two Army surplus overhead projectors, but there wasn’t any money to rent the extra projectors I knew I’d need to make a difference in that big hall. I didn’t want to do something if it wasn’t going to have an impact, so I passed.

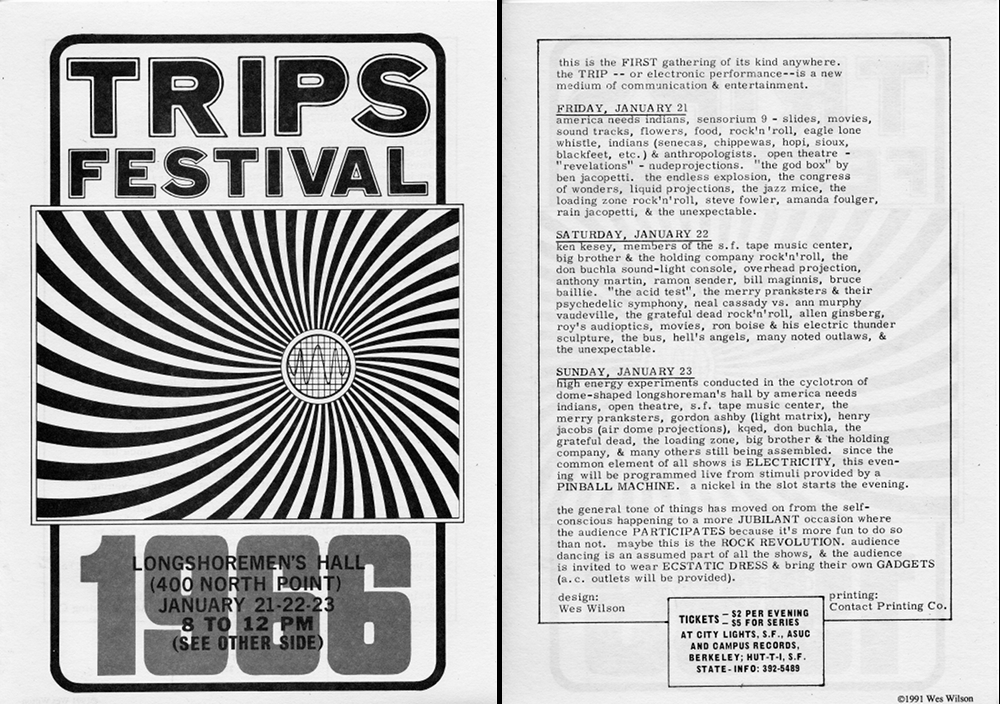

The lineup at the Trips Festival (click to enlarge) includes numerous references to “liquid” and “overhead” projections, as well as “Anthony Martin,” who would go on to do the first light shows for Bill Graham at the Fillmore. (Via Wes Wilson)

Collectors Weekly: So, those early Longshoremen’s Hall shows had no light shows?

Ham: Well, I think they rented one of those big spotlights, but there were no stage lights or light shows. Each weekend, there was a band from L.A., like The Mothers or Lovin’ Spoonful, plus a band or two from here—The Charlatans played all three weekends; Jefferson Airplane played one or two. The Mothers, led by Frank Zappa, played the last of the three shows. To me, they sounded like the sort of band you’d hear on the edge of town, playing at a place where people went to dance on weekends. They hadn’t turned psychedelic yet, and unlike the San Francisco bands, they didn’t have to stop to tune up. They’d just change key and launch into the next tune; they were pros.

Meanwhile, I had built a larger studio a few blocks away from my place on Pine Street in an abandoned garage on Laguna Street. Bob Fine continued to assist me there, and also at the Tape Music Center, where I did a performance in January of ’66 that got good reviews from Philip Elwood of the San Francisco “Examiner” and Alfred Frankenstein of the “Chronicle.”

That light show included live and recorded sounds by Bill Spencer. During that period, I was collaborating with a lot of different musicians. I’ve already mentioned Christopher Tree. Jerry Garcia did a session with me, and James Gurley, who became the lead guitarist of Big Brother, did several, even before he was playing the electric guitar.

The person I played with the most during this early period was a guitarist named Oscar Daniels. Oscar grew up in San Francisco, his father was a doctor, and he was one of the few African Americans in the hippie scene, although I don’t think that term was even being used yet. Oscar’s style was very lyrical, in part because he had taken a class with the great Indian sarod player Ali Akbar Khan. He would play these improvised things that were kind of like Indian ragas. Oscar was also friends with members of the Great Society when Grace Slick was still in that band. He used to sit in with them at the Avalon, but I don’t think he was actually a member.

Rock promoter Bill Graham capitalized on the excitement, and ticket sales, of the Trips Festival by promising more of the same for his first show at the Fillmore. Tony Martin, who had done some of the light effects at the Trips Festival, did the Fillmore’s lights for Graham’s first shows there, as well as the Family Dog’s first shows at the Fillmore. When the Family Dog moved to the Avalon, though, Martin’s name was still on the poster, even though Bill Ham did the lights. (Left: Poster by Peter Bailey, via Psychedelic Art Exchange. Right: Poster by Wes Wilson, via D. King Gallery.)

Collectors Weekly: January of 1966 brought the Trips Festival, and then from February to April, the Family Dog and Bill Graham traded weekends at the Fillmore. How come you didn’t to the lights for any of those shows?

Ham: Bill Graham had helped produce the Trips Festival. An artist named Tony Martin, who had been involved with the Tape Music Center, which was very much a part of organizing the Trips Festival, had done some of the lights at the Trips Festival. So, when Bill produced his first rock show at the Fillmore, with a poster that read “with Sights and Sounds of the Trips Festival!” naturally Bill turned to Tony for the “Sights.” Chet Helms, who was running the Family Dog by then, also used Tony for his first Family Dog shows at the Fillmore, but the poster for the first Family Dog show at the Avalon, which lists Tony as doing the “lights and stuff,” is a mistake. I did that show.

Collectors Weekly: What was your set-up at the Avalon?

Ham: Throughout this time, I only had two overhead projectors, with Bob Fine assisting me when it was time to switch dishes. Bob would take a dish whose colors were getting muddy and give me a fresh one, to keep the show going. We knew two projectors would not be enough to fill up the Avalon Ballroom, so for that first weekend at the Avalon, April 22 and 23, we rented an extra overhead from McCune Sound.

A good part of what we were trying to figure out at those first Avalon shows was how to get enough projected imagery into that big room. When Tony Martin did a light show, he had a partner who was a filmmaker, so they could have the image on the overhead going at the same time as a film running in the background. Neither Bob or I were filmmakers, though, so we mostly had to make it work with just those three overheads.

Until that first show at the Avalon, Bob hadn’t done any of the actual work on the projector—he was strictly an assistant. That first night, I tried to do everything myself, but five or six hours is a long time to do a light show by yourself, so by the second night at the Avalon, Bob was working on the projectors as well. The light show would always be known as “Light by Bill Ham,” but Bob Fine was a performing member as an artist from that point on. It was natural evolution.

When Bill Ham complained to the Grateful Dead’s soundman, Owsley Stanley, that his light show would not look very good on the band’s speakers, Stanley had them painted white. Note the misspelling of the band’s name on this poster. (Poster by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: How important was the music to you? In other words, if you were doing lights for a band that you didn’t care for, was it kind of a drag?

Ham: Some bands were more fun than others, but in the beginning, we hardly knew what band was going to be there from week to week. Everything was a surprise, and that made it interesting. Basically, we were making everything up on the spot. My main concern was just to make something beautiful that filled the room and, of course, that related to the music.

Collectors Weekly: What did bands think of having light shows projected onto them?

Ham: Well, if it was Oscar sitting in with the Great Society, he had played with me before, so there was a certain amount of back and forth—of the lights relating to the music and vice versa. Mostly, though, I didn’t tell the musicians how to play, and they didn’t tell me how to do the light show.

During one my weekends at the Avalon, we had hung white plastic on the walls behind the band so we’d have something to project onto. At some point I took a break, and when I came back, the Grateful Dead’s roadies had moved all of their equipment onto the stage, completely blocking our white background. Well, I went over to Owsley Stanley, who was the band’s sound guy, plus a few other things, and explained what we were trying to do. He heard me out and said that he couldn’t do anything about it tonight, but he’d have the crew paint all the speakers white for the next day. And they did. At that point, the bands weren’t really performers in the showbiz sense—they provided the music and we provided the lights.

For the most part, the local bands were just happy to be there, while the L.A. bands were more professional, but we got a lot of positive responses and cooperation from them, too. For example, during his set break, Captain Beefheart came by the light booth because he wanted to see how it all worked. Another time, one of the groups, I think it was Love, had brought all these funny little spotlights with them, the kind you might set up in a nightclub or something, because they’d heard the Avalon had no stage lighting. So we had to tell them they couldn’t use their lights because we’d be projecting onto them, their equipment, the wall behind them, everything. Initially, they grumbled a bit, but after the first set there were no complaints. They became fans because they liked what was happening.

Love and Captain Beefheart (another poster misspelling) were big fans of Ham’s light shows when they played the Avalon. (Poster by Wes Wilson, via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: And what, exactly, was happening?

Ham: People danced. Did I tell you the story about Bo Diddley? His first set ever at the Avalon was hard to relate to because it was like a nightclub set, like he might do for an audience that was sitting down and drinking. For the most part, that’s what the crowd at the Avalon did during his first set, too—sat down, right on the floor. After his set, Quicksilver Messenger Service took the stage while Diddley hung out near the food at the other end of the ballroom and watched as everybody got up and danced and danced and danced. When he came back for his second set, he took the microphone and said, “I haven’t played for a dance in years. You people get up and dance!” And he proceeded to play a set for dancing. I thought that was so hip for him to pick up on that.

Collectors Weekly: How important was the open floor plan of places like the Avalon, the Fillmore, and Winterland to the San Francisco music scene?

Ham: Dance is a basic human activity. The fact that people could get up and dance, that they weren’t confined to seats, was a very important part of seeing live music in San Francisco. It was only later that musicians learned how to be performers for audiences glued to their chairs.

Dancing had definitely been an important element of the first Family Dog dances at Longshoremen’s. The whole point was to break what in the theater world is called the fourth wall, to get people to participate, not just to be observers. That was especially true at the Avalon. In Bill Graham’s biography, Eric Clapton remembers that “Most of the audience would sit on the floor and just stare at the light show,” but at the Avalon, with the exception of that first Bo Diddley set, if you didn’t dance, you’d better get out of the way.

Bill Ham found himself double-booked on the first weekend in July, so Bob Fine did the shows in Monterey. (Poster on right by Wes Wilson, both via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: You mentioned earlier that you often didn’t know who would be playing from one week to the next. Were things really that unstructured?

Ham: Oh definitely. After a weekend’s worth of show, we’d take all the projectors out of the Avalon and bring them back to the studio on Laguna Street. It was hard to tell what was going to happen the next week because Chet Helms, who ran the Avalon, never seemed to have enough money. So in the summer of ’66, when a promoter in Monterey asked me if I wanted to do the lights for a show with Big Brother and Quicksilver, I agreed.

About halfway through the week before that show, Chet contacts me to say that he’d scraped together the money and that we were on for the weekend. Now I’m booked to do two light shows in two places at once, so Bob Fine, who used to be mistaken for me anyway, stood in for me in Monterey. I went down there to make sure everything got set up properly, and when I got back, Chet said, “Bill, from now, on you’re booked every weekend.” At some point, Chet even invited me to be a partner with him and Bob Cohen, who was the Avalon’s soundman. With us as partners, that took care of sound and lights for Chet.

Bill Ham enjoyed doing shows for the Great Society because he and the band’s guest guitarist, Oscar Daniels, did sessions together in Ham’s studio. At the time of this show, Grace Slick was still singing with Great Society, but would leave the band later in the year for Jefferson Airplane. (Poster by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: During the Avalon period, did your setup remain pretty constant, just three overheads?

Ham: No. Somebody lent me a 16mm film projector, so we added that. I think we may have ended up with as many as four overheads and probably a slide projector or two. We also had a projector that was really bright, which we aimed through sort of a color wheel.

I still didn’t approach my work intellectually, though—it was still mostly trial and error. One of the biggest factors was the number of overhead projectors available. My way of working wasn’t about using multiple projectors to create multiple images, but using multiple projectors to create a single image.

Collectors Weekly: But multiple projectors must have at least given you flexibility as an artist, right?

Ham: It’s actually more about allowing you to create a continuum of imagery. Let’s say you can’t do any more in a dish or set of dishes on a projector, either because you want to move on image-wise or you need to sort of cleanse the palette. Another projector lets you evolve the image without removing an aspect of it abruptly. That’s the continuum I’m talking about that results in a live, spontaneous mix on the wall.

Collectors Weekly: How did you keep the change from seeming abrupt?

Ham: That was achieved with dimmers, but that required a bit of custom rewiring. The first thing you’d do is rewire the fan’s connection to the bulb in the projector so that if the fan wasn’t running, you could not turn on the bulb. The idea was to have the fan running continuously, so that when you dimmed the light in the projector, the fan stayed on. That helped bulbs last longer, but it also gave you a way to reduce one projector’s brightness and increase another, which affects what you’re doing on the wall.

Ham and the other members of Light Sound Dimension did a rare, non-Bill Graham produced show at the Fillmore in 1967. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: Your last show at the Avalon was in August of 1966. Why did you step away from that scene so quickly?

Ham: For much of that summer, the Family Dog was a three-way partnership—Bob Cohen, Chet Helms, and me. Then they added a friend of Bob’s from New York to the mix. That guy didn’t have a clue about anything that was going on, but he had been the manager of an apartment building in New York City, so I guess Chet thought he would be able to help with the business side of things. Eventually, and for more reasons than just that, I withdrew from the partnership, and that was also when I stopped doing the Avalon’s lights.

Beyond that, the Avalon was an example of my work that related to people being physically, actively involved in the show—getting up and dancing. I liked that, but I also liked performing for an attentive audience, the concert form, if you want to call it that, which began in the studio and continued even when I was working at the Avalon.

At one point in ’66, I had invited a guy named Frank Werber, who was the manager of the Kingston Trio and a few other acts, to my studio, and he brought these jazz musicians with him—Fred Marshall, Noel Jewkes, Jerry Granelli, and a guy named Malachi. Eventually, they came back, we did some sessions together, and out of that evolved a light show with live jazz called Light Sound Dimension.

The core musicians in the first incarnation of Light Sound Dimension were Fred Marshall (left) and Jerry Granelli (center), seen in this circa 1968 photograph on California Street with Bill Ham. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: This is probably a silly question, but was the name Light Sound Dimension taken from the initials LSD?

Ham: We didn’t make it up with that necessarily in mind. Light and Sound were obvious, so the question became Light Sound and what? Fred came up with the Dimension part. Anyway, eventually, Gerald Nordland, who had come to town to be the new director of the San Francisco Museum of Art, saw one of our studio sessions. Afterwards, he asked me if I’d be interested in doing a show at the museum, and I told him that sounded like a good idea. Once he became director, we were the first program he scheduled.

Bob Fine and I had a week to get ready. They gave us the big room on the top floor of the museum’s old location on Van Ness. The room had a big skylight in the ceiling, but the museum had put a temporary covering over it, which was painted white. Therefore, our first job was to isolate the light in the room so that the focus would be our projections. We actually went up to the skylight, took all the plywood covers off, painted them black, and turned them over, so the black sides were facing down. Inside the room, we made temporary walls out of black plastic, which we hung from the ceiling ourselves. Then we put a light-show booth on the stage so we could project against the far wall, over the heads of the audience. All that took several days.

A performance by Light Sound Dimension at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1967 led to a pair of shows at UC Berkeley’s Pauley Ballroom a few weeks later. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

The shows were performed over a weekend in February of 1967, and more people attended than had ever showed up for a special program at the museum. Alfred Frankenstein of the “Chronicle” gave us another positive review, but afterwards, we were back to figuring out what to do next. The San Francisco Museum of Art shows did lead to a couple of performances at UC Berkeley’s Pauley Ballroom, and we got our first taste of working behind a rear-projection screen when we did a series of shows that summer at a little theater in Berkeley’s Live Oak Park. But our music was jazz, the antithesis of rock ’n’ roll, so we weren’t right for places like the Avalon. There just weren’t too many options for us.

Then, one day, I happened to be walking down California Street and came upon an empty storefront close to the corner of Polk Street. For some reason, I thought I would check it out, and it turned out the building was owned by Peter Blasko, the person who had originally owned the building I managed on Pine Street. It was a total coincidence. I told him I’d like to try to put a light-show theater in there. He said he didn’t see how, but agreed to rent it to me for something like $500 a month.

Light Sound Dimension (with Bill Ham at lower left and Bob Fine to Bill’s left) getting ready for a show at the California Street studio, circa 1968. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

It was an old brick building that was divided in the middle. Without knowing anything about what we were getting ourselves into, Bob Fine and I knocked down the temporary walls and started imagining how we’d turn it into a light-show theater. It didn’t take long, though, for building department to notice what we were doing. So now we had to learn all about permits. Luckily, we managed to find a young architect who would draw up some plans for the fire exit and such.

In the meantime, I had gotten in touch with my Red Dog cabinet maker, Kurt Banks, who agreed to help us figure out how much lumber to order, and also to build things like doors and stairs for us. Through some miracle, I was able to borrow the money to buy a rear-projection screen, so Kurt also helped us figure out how to build a frame that would hold it up in front of the stage. Even more miraculously, one morning in North Beach, Bob and I came across about 50 theater seats in a debris box. They had come from an old theater across the street that was getting new seats. So, just like that, we had 50 seats for our theater. The rest of the space was an open floor, but hippies were kind of accustomed sitting on the floor at that point.

The original art for “Zap Comix” No. 2 were shown in the lobby-gallery of the Light Sound Dimension studio on California Avenue in 1968. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

Within a few weeks, we had converted a divided storefront into a light-show theater holding 200 people. It even had a lobby, which we turned into a gallery space. We had a show there by a group of Japanese artists from the Kyushu province, who were now living in Japantown. A month or two after that, we showed 56 original drawings by artists who drew for “Zap Comix,” including Robert Crumb, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, and S. Clay Wilson. There was one more show after that by an artist named Pat McFarlin, who made these sort of sculptural drawings with lots of rock ’n’ roll imagery.

Collectors Weekly: How often did Light Sound Dimension perform?

Ham: Beginning in January of 1968, we performed every week, usually two shows a night on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, with maybe one show on Sundays. Something like that. We were struggling the whole time and basically never made any money, but art critics liked it—as Alfred Frankenstein put it, “there is probably no theater like this one anywhere else on earth.” I’m pretty sure that was true.

Collectors Weekly: What did you do after you closed the California Street theater?

Ham: I built a 4,000-square foot studio on Shotwell Street in the Mission and ran that for about a year, but I’d heard jazz had a wider audience in Europe. I was exploring ways to keep doing what I was trying to do, so figured maybe Light Sound Dimension would go over well in Europe. I had a friend in San Francisco named Ken Connell, who’d bought a house in Amsterdam and invited me to come over and stay. Ken said he’d turn me on to all these people in Europe who might be interested in Light Sound Dimension. Coincidentally, I’d been seeing a young lady from France named Sophie Houdet, whose visa was up and had to go back to France. So, in 1970, I got myself a 45-day plane ticket and arranged to meet Sophie in Amsterdam at Ken’s, who was better known at that time by his nickname, Goldfinger.

Ham was promised that Light Sound Dimension would be credited on this 1968 poster for a show at the Carousel Ballroom (it became the Fillmore West that summer), but the group’s name was abbreviated to its initials. (Poster by Stanley Mouse, via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: Goldfinger, as in the legendary drug runner?

Ham: Let’s say “importer,” or maybe “privateer.” Ken started out flying into Mexico to bring back a few pounds of pot and sell it on campuses like San Francisco State. Then his business, shall we say, evolved. By the time of my Amsterdam trip, Ken was smuggling hash out of Lebanon. It’s a famous story in some circles. He’d arranged to fill a twin-engine plane with a load of hash, and he’d hired a former Strategic Air Command colonel to fly it. The guy was apparently quite a pilot. So he and Ken flew into Lebanon for the pick up, landing in a field that had been scraped roughly flat with a bulldozer. But as they’re refueling and loading the hash, the Lebanese army arrives, and suddenly there’s a shootout.

In the middle of all of this, the pilot takes off and gets them out of there. They had loaded the hash on board but hadn’t finished refueling—they were supposed to have pumped enough fuel to fly to Amsterdam, which is an open port, but they hadn’t pumped enough for that. By now, NATO is on alert, everybody’s looking for them, but the pilot got them across the Mediterranean undetected because he flew really low. Even so, he still had to land somewhere to refuel. Ken wouldn’t dump the hash in the Mediterranean, which turned out to be a big mistake, because as soon as they landed on whatever island it was off Greece, the authorities confiscated the plane, and everyone went to prison.

Collectors Weekly: Meanwhile, you’re in Goldfinger’s house in Amsterdam.

Ham: Yeah. It was a little shaky staying there, and it didn’t help that Ken’s house sitter, the Dutch poet Simon Vinkennoog, happened to be a very public advocate for cannabis legalization—he was definitely not low profile. So when Sophie arrived, we moved into a cheap hotel in the red-light district to lay low. I’d just about run out of money when, to make a very long story short, I ran into a friend named Doyle Nance from California, who’d been in on the opening of the Red Dog Saloon. Within about 15 minutes, we were in his car, heading to Paris.

Right away, we tried to see if there was a way we could do a light show in Paris. Sophie was now my translator, and she learned that by coincidence, in a month or two, the National Museum of Modern Art was set to have a light-show festival. Sophie was able to speak with the woman in charge, and they arranged for us to be part of the festival. At the same time, Sophie, who grew up in France about 30 or 40 miles outside of Geneva, Switzerland, had been calling her contacts in Geneva. It turned out there was going to be an event in Geneva before the Paris festival, so that’s where we went next.

Before I had left San Francisco, I had made, with Kurt Banks’ help, traveling cases for my projectors and sound equipment, which by then consisted of seven overhead projectors, a Fender Dual Showman amplifier, and some speakers. So we had the cases sent to Geneva, since that’s where we would need them first. Bob Fine arrived more or less at the same time, but I was the one who went to the airport to get them. Naturally, I didn’t have any of the proper deposits or paperwork or whatever was needed, but somehow or other we got it in anyway, with a kilo of pot hidden in the equipment. It was just in time because we were supposed to perform that night in Geneva.

The posters that Bill Ham commissioned in 1970 for Light Sound Dimension shows in Europe were confiscated upon arrival in Geneva, Switzerland, because customs officials thought the group’s initials were promoting drugs. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

Collectors Weekly: Wait a minute—there was a kilo of pot inside your equipment?

Ham: Yeah. That kept me going for my first year in Europe.

Collectors Weekly: You mean by selling it off?

Ham: No, no. Smoking it. I wasn’t about to sell it! Anyway, the performance was supposed to be that night, so we were cutting it pretty close, but it got canceled by the mayor of Geneva, who thought the poster for the overall event was obscene.

Our posters for Light Sound Dimension also got us into trouble. The idea was that they’d be generic, with a blank space at the bottom for wherever we were performing in Europe. Bob got the posters made, which featured a photo of a light show and the name of the group, Light Sound Dimension. The group’s initials, “LSD,” were also printed, but in huge letters, with the group’s name in much, much smaller print. So when Bob landed at the airport in Switzerland with the posters, the customs officials opened up the package and there were the letters “LSD” staring back at them. They didn’t like that, so we weren’t able to use that poster, either.

After Bob Fine left Europe, Sophie Houdet assisted Bill Ham during Light Sound Dimension performances. (Via Bill Ham Lights)

In the end, Bob and I did the Geneva show the next night, accompanied by a recording of Fred Marshall and Jerry Granelli. After we emptied the traveling cases of any foreign matter, we shipped everything to Paris for the upcoming show at the National Museum of Modern Art. By then, Bob’s girlfriend and dog had arrived from the United States, so we bought the oldest, cheapest car we could buy in Switzerland, a VW bug, and drove it to Paris. Ultimately, we did two shows at the museum, and a week or so later, we performed at Cité University.

We stored all the light-show equipment in Paris because we didn’t have any way to get it back to the village where we were living in a house owned by Sophie’s family. Actually, it was a large, French Alps-type barn. Nobody had lived in it for quite a while when we moved in—there was ice on some of the inside walls—but we got an oil heater going and started fixing it up. That became our home base for most of the rest of the time we were in Europe.

Then, in 1971, a filmmaker we knew told us about a big, free rock festival that was being planned outside Paris. The promoter, Jean Bouquin, wanted to do a kind of European Woodstock, and the guy we knew was going to film it. He thought it would be a good idea if Light Sound Dimension did the light show.

The first step was to meet Jean Bouquin, so they sent us a couple of roundtrip tickets to Paris. Bouquin was famous for having owned a boutique where Bridget Bardot shopped; now he wanted to throw this free rock festival. He’d heard about me from the filmmaker, but he wanted to see my portfolio, so I showed him this and that to prove I was a light show.

Then I asked him to prove he was a festival. Right away, he started telling me about all the bands that were going to be there—French bands, English bands, the Rolling Stones, Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe. Since the festival was only about two weeks away at that point, I asked to see their signatures on contracts. Well, he told me he was having trouble getting in touch with the Airplane, Dead, and Country Joe. I happened to have my pocket address book with me with all their phone numbers in it, so I pulled that out. That really impressed him, especially when he went into his office and the numbers actually worked, although, because of the time difference, nobody had picked up.

We agreed to stay overnight and help him out, and got a tour of the festival site the next day. By then, they were frantically building stages for the bands, and the clock was ticking. At some point, Bouquin asked me if I would fly to San Francisco and invite some of the bands personally on his behalf. So the next day, or something, I flew to San Francisco and went directly to Wally Heider’s studio, where the Airplane and Dead were both recording. I spoke with the Airplane, but they said they couldn’t get loose. Then I spoke with Garcia and the Dead’s manager at the time, and it sounded interesting to them.

Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead at Château d’Hérouville, 1971. (© Rosie McGee)

Collectors Weekly: So you got the Grateful Dead to Europe a full year before their famous Europe ’72 tour?

Ham: I’m the guy. So, the Dead’s manager gets Bouquin on the phone, and Bouquin offers to put them up in this castle he had access to—he figured it was just five guys in the band, plus a manager. But the Dead’s entourage at that point included 22 people and 5 tons of equipment, and they wouldn’t agree to do the festival unless they could bring all their people and play on their own equipment. After Bouquin got over the shock, he agreed.

I flew back to France with the Dead. I think I had a regular ticket, and they had first class or something, but we all flew back together. In addition, my deal with Bouquin had been that if I could get the Dead or Airplane to play at his free festival, I’d do a free light show, but he’d have to fly the Light Sound Dimension jazz musicians over. So five other people came over, too.

Bob Fine had rounded up all our stuff, and when we finally got to the festival site, it was night; everything was supposed to start the next day. Meanwhile, lots of people had heard about this free festival, so crowds had begun arriving. At one point, the promoters told us we’d all be sleeping in a little tent, five of us, but I wasn’t having any of that, so they finally agreed to put us up in the castle, a place called Château d’Hérouville, with the Dead.

Then the rains started. By now, there were lots of people at the festival site, which was on private property but surrounded by tons of police carrying serious guns. The rains got worse, the French audience got really restless, and they ended up canceling the whole thing.

Bill Ham (partially obscured by a microphone stand) and other members of Light Sound Dimension preparing for their poolside performance at Château d’Hérouville in 1971. (© Rosie McGee)

Meanwhile, we’re staying in this walled-in chateau, which had a recording studio in the basement, for several days. Naturally, someone was trying to salvage the fact that the Grateful Dead and 5 tons of equipment were outside of Paris. Reportedly, a competing promoter from London came down to try and book the Dead in England, but when he arrived to work out a deal with one of the French festival’s promoters, some gangsters had been sent to the meeting instead and broke the guy’s hands. At least, that was the story I heard.

Collectors Weekly: They actually broke his hands?

Ham: Uh-huh. That kind of ended the talk of going to London. But the night before the Dead left, there was a party for the mayor of a nearby village at the chateau. A lot of the fans who had come for the concert found out where the band was staying, but nobody could get over the walls, and they didn’t let anybody in. Because it was summertime, the Dead set up their equipment by the swimming pool and played a great set. They started early, before it got dark, and after they finished, Light Sound Dimension performed.

Collectors Weekly: What did Light Sound Dimension do in Europe after that?

Ham: The Light Sound Dimension musicians had arrived with no money, no anything. Eventually, we were invited by Bouquin to play a series of free shows in Montreux, Switzerland, at Bouquin’s brother’s art opening, so we rented a car and a van and headed east. It didn’t help our financial situation, but the guy who produced the Montreux Jazz Festival, Claude Nobs, saw our shows, and through him, we were able to do a couple of subsequent performances that actually had budgets. After the Light Sound Dimension musicians went back to San Francisco, we met and performed with other jazz musicians. Bob Fine stayed about a year, and after he left, Sophie assisted me on the light shows. We were there for two more years, during which our daughter, Tara, was born. We did about 20 performances overall, including collaborations with a band in Geneva, some shows with a French jazz group called XTET, performances at the Nancy Jazz Festival in France. That sort of thing.

In 1973, Bill Ham, Sophie Houdet, and their daughter, Tara, hitched a free ride from Geneva to Los Angeles aboard a short-lived alternative airline called Freelandia. (Via linkbeef.com)

Collectors Weekly: How did you get back to the United States?

Ham: One day in the fall of 1973, shortly after the Nancy Jazz Festival, we were back at the farmhouse. It was a beautiful day, but I had $5 in cash in my pocket, and that was starting to get old. Some friends from Geneva had come by with their children, to play with Tara, and one of them mentioned that a planeload of hippies from San Francisco had just arrived in Geneva on a big yellow plane flown by an airline called Freelandia. There was a rock band on board called Stoneground, and they were going to play that night at some club in Geneva, and then the plane was flying back to San Francisco tomorrow. I knew one of the singers in the band, Annie Samson, and a guy who was kind of the band’s manager, so we left Tara with some friends and Sophie and I drove to Geneva.

We got into the club before the show started and met up with Annie. And I asked her if I could get a ride back to San Francisco with the band. She laughed and offered to introduce me to Kenneth Moss, the guy who founded Freelandia. So I met him, and asked for a lift, too, but didn’t get an answer. During the show, Annie dedicated a song to me, and afterwards we all went to dinner, when I asked Moss again if I could bum a ride. After he finally agreed, I said, “Oh, and by the way, I’ve got a wife and a baby, too.” By then, though, he couldn’t back down, so we rushed back to the house, grabbed Tara, packed a suitcase, and were at the airport and on a plane the next morning. Turns out the plane only went as far as L.A., but Moss was a good guy—he bought the three of us tickets from there to San Francisco. So, yeah, three years on a 45-day pass.

Was Levon Mosgofian of Tea Lautrec Litho the Most Psychedelic Printer in Rock?

Was Levon Mosgofian of Tea Lautrec Litho the Most Psychedelic Printer in Rock?

All-Night French Fries with T-Rex: Seattle's Trippiest Rock-Poster Artist Tells All

All-Night French Fries with T-Rex: Seattle's Trippiest Rock-Poster Artist Tells All Was Levon Mosgofian of Tea Lautrec Litho the Most Psychedelic Printer in Rock?

Was Levon Mosgofian of Tea Lautrec Litho the Most Psychedelic Printer in Rock? Did the CIA's Experiments With Psychedelic Drugs Unwittingly Create the Grateful Dead?

Did the CIA's Experiments With Psychedelic Drugs Unwittingly Create the Grateful Dead? MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving…

MusicIn so many ways, music is the soundtrack of our lives—whether we're driving… Fine ArtFor as long as there have been civilizations, humans have made art to inter…

Fine ArtFor as long as there have been civilizations, humans have made art to inter… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

This was fascinating reading ! I worked for the Jefferson Airplane in those days (for 17 years actually). Our lightshow, Glenn McKay’s Headlights, travelled with us all over the US and on our European tour too. My friend (still) Joan Chase started Heavy Water and had lightshows in major museums in the US. The current Bill Graham exhibition (Rock and Roll Revolution) at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in SF is fantastically well done. Thanks to Bill Hamm for all of his work, and to Rosie McGee for passing this on…

I saw Jefferson Airplane & Glen McKays Headlights at Fillmore East, NY August. ’69, a couple of weeks prior to Woodstock (no, I did not go…. should have…). The light show as I remember it, was more engrossing and dramatic than the Joshua Light Show; large images, designs, etc. all merging into and between one another and very colorful. At least that’s how I remember it some 47 years later.

Un ptit article interessant sur le vieux magicien Bill Hamm ui est un pionnier du. LIGHT SHOW que je considere comme un innovateur ijih

In 1970 and 71 myself and two friends had a similar light show in Michigan. We used overhead projectors with clear baking dishes into which we dropped colored oils on water and stirred them into motion, sometimes with the help of a goldfish. We used slide projectors with rotating polarizing lenses in front of them, with different kinds of tape on the lenses to create kaleidoscope effects, and projected movies backwards and upside down, crashed planes reassembling into the air etc.Fun times!

I was enthralled by every word and pic here! Another great one Mr. Marks!!

Thomas(Brunswick).

great job Ben. It wonderful to read what Bill remembers of those early days. He is one of the true originals; one of the people who created the scene

Beautifully put together nostalgia trip…Thank You!

Very, Very, well done !!! I really enjoyed reading, or should I say re-living the 60’s with Bill Ham ! Rock On, and Happy Trails !!!

Great article. I lived next door. I thought it was 1836, but maybe it was 1834. Had the room with the sunroom in the front. I think the same guy owned it as 1836 Pine, and I can’t for the life of me remember who I and everybody else was paying rent to. Maybe it was Bill. Anyway, I read every word with such great pleasure. Nothing better than history by the people who were the history. I remember most of the people mentioned. Thanks.

And if anyone remembers me, Hello. I live in Budapest now.

I am a longtime musician and have also written for many music industry magazines. I just wanted to say what an EXCELLENT story this was. I went to the Fillmore East several times when I was a 15-17 y.o. kid and remember the light shows well. Just fascinating to hear about the genesis of the craft from someone who was there and instrumental in it all. Thank you.

What a great article thank you so much! I’m a little late with this post and it ties a lot of things together that were part of my enlightenment. I’ve worked with Bob Cohen at Lumiere/Bob Cohen Sound doing live remote broadcast engineering with KSAN and Chamberlain various electronica devices. Bob is a genius and and I learned much from him. I’ve worked at FM productions as an audio engineer and BGP management as Road Manager. I feel totally blessed that I came to the Bay Area not knowing anybody and fell into the music scene and worked with some of the most iconic people ever. I’m thanking the universe every single day that I got lucky to be able to do what I love, hang with the people I admire, and be rewarded in doing so. When I was working with John Cipollina I was introduced to Mark Unobsky and instantly became lifelong friends. Mark was Johns’ de-mentor. Joyce are you still out there somewhere? LMK. I met Bill Ham briefly at the Red Dog 50th reunion in Virginia city and met some new friends as well. I started collecting posters and handbill’s in 1967 so this article was special on that front as well. this day I still have my complete collection of handbill’s for both Family Dog and Bill Graham Presents in presentation binders in a large safe. I am sending much love and light to those who have helped me in the past as I remain your loyal minion.

;-)””

In 2008, I attended a party at Bill Ham’s residence in SF. A dear friend of mine (who was very involved in the 60’s SF rock era) was invited to the party, but could not attend, and asked me to go in his place. I was reluctant to go, because I didn’t know Bill or anyone at the party, but my friend assured me that I would enjoy the people and the party. So, I decided to go, and drove to SF, and knocked on the door. A white haired gentleman with a long flowing white beard (Bill) opened the door. I explained that my friend (who I instantly learned Bill was quite fond of) asked me to attend the party in his place, whereupon Bill loudly and joyfully exclaimed, “Come on in! Jack and a joint?” holding up a bottle of Jack Daniels in one hand and a fat doobie in the other! I met great people, and one guy, after we talked for a while, warmly said, “You’ve found your tribe.” It was a fantastic evening, and Bill treated us all to a light show. I didn’t know at the time what an icon and huge figure Bill was in the 60’s psychedelic rock scene, but soon learned of his legendary stature. I am forever grateful for meeting him, his friends at the party and the memorable experience of that magic night.

I worked at the Avalon for a year in ’66. My girlfriend was Chet’s secretary and she got me the job. Occasionally, on my break, I would go upstairs to work the light show which would be to move the curved pieces of glass with different colors in time with the music. I also used to hang out at the Red Dog and I remember the light box on the stage next to the band. It would change colors as the music would change as it was hooked up to the amps. When 2001 A Space Odyssey came out I went over to Bill’s house because we were going to see it together and as we heard it was psychedelic we decided to get stoned for the movie. But the psychedelic part was at the end and we had come down by then.