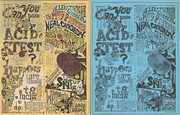

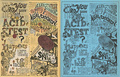

This year, senior citizens around the San Francisco Bay Area are celebrating the 50th anniversary of a three-word phrase coined in a 1967 press release. From April through August, you’ll find many of these former hippies, their flowing gray hair an incongruous contrast to their brightly colored tie-dye, shuffling through the normally serene galleries of the De Young Museum, where they pause to admire indecipherable concert posters, hand-patched bell-bottom jeans, killer rock photography, and re-creations of psychedelic light shows, all of which have been gathered together for an enormous exhibition titled “The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll.”

“Written for tourists by the city’s consummate insider, Caen’s Guide paints a picture of a city whose quaint customs no doubt made so many people 10 years later want to turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

Fifty years ago, the authors of the press release, an ad-hoc group of neighborhood activists and cultural entrepreneurs who called themselves the Council for the Summer of Love, couldn’t have imagined that so much high-brow attention would one day be lavished on their scruffy scene. Indeed, at the time, they were more focused on the fact that the idealism encapsulated in their group’s name was being perverted by commercial interests keen on selling records, clothing, and soda pop to millions of kids. But they also knew that the national media hype surrounding the events occurring in neighborhoods like the Haight-Ashbury and nearby Golden Gate Park was about to lure tens of thousands of young people to San Francisco in search of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. So, somewhat uncharacteristically, the members of the council were attempting to be prepared for the onslaught.

Today, it’s difficult to think about San Francisco as anything but the birthplace of the hippie counterculture, the centerpiece of which just about always revolves around that nostalgia-soaked three-word phrase. But in a weird way, the venture capitalists taking meetings on the fancy new benches in South Park, to say nothing of the kombucha-chugging hipsters who have ruined the Mission District, would probably feel more at home in the San Francisco of 1957 than the city of 10 years later, at least according to Herb Caen’s Guide to San Francisco and the Bay Area, which was published 60 years ago.

Top: The Bay Bridge with the Ferry Building in the foreground. Above: Coit Tower. All illustrations by Earl Thollander, from Herb Caen’s Guide to San Francisco and the Bay Area, published in 1957.

Written for tourists by the city’s consummate insider, newspaper columnist Herb Caen, Caen’s Guide paints a picture of a city whose quaint customs no doubt made so many people 10 years later want to turn on, tune in, and drop out. In Caen’s descriptions of the city’s sights, restaurants, and watering holes, as well as the charming illustrations by Earl Thollander, San Francisco comes off as irredeemably square, which, of course, is just so cool.

How square? Consider Caen’s description of the typical San Francisco male’s attire: “He dresses in dark, generally conservative clothes. He wears a hat, even on warm days (although on very warm days he might unbend to the point of carrying it in his hand).” We’ve all seen this guy, albeit with piercings, ordering a pint of some sort of Belgian beverage down at the end of some bar, right? Caen’s women, on the other hand, dress in less-familiar garb: “Women seem to feel most at home in San Francisco in suits. Mink coats, of course, are highly acceptable any time—and stoles come in handy too.”

Seal Rocks and the Cliff House. The rocks are still there, as is a remodeled version of the Cliff House.

In Caen’s Guide, these men in hats and women in stoles stalk restaurants like Fior d’Italia, which is no longer in its “handsome new quarters that embody the latest advances in restaurant design,” but still serves a menu that “covers almost the whole range of Italian cookery.” Caen also steers his readers to the Hang Ah Tea Room, which in 2017 is considered the “oldest standing and functioning dim sum house in America.” In 1957, Caen felt obliged to warn his readers that “You will find very few Caucasians in this tucked-away spot,” which, alas, is similar to how he describes Chinatown as a whole: “The gunmen of rival tongs no longer take potshots at each other in its back alleys, the poppy perfume of opium can seldom be sniffed in its dark doorways, and the slave girls weep no more in its brothels—but for all that, San Francisco’s Chinatown is still the city’s most fascinating and authentic foreign colony.”

Better are the author’s paragraphs in the book’s “Life After Dark” section, in which he directs readers to Bimbo’s 365 Club, where “the chorus girls are appropriately frisky” (whatever that means) and “swimming enthusiasts” (ditto) crowd around the “Girl in the Fishbowl,” in which a “mirror illusion” of “a live, nude girl appears, greatly reduced, to be swimming in a revolving bowl of water.” Ah, the bad old days.

San Francisco’s modest 1957 skyline, as seen from the Bayshore Freeway.

Other entries suggest that even though the city lacked a steady schedule of rock concerts at the Avalon, Fillmore, and Winterland, like it would enjoy in 1967, it didn’t want for entertainment. Over at the “hungry i,” which is now just another strip club in North Beach, “San Franciscans of all strata” sat in canvas chairs to catch comedians such as Mort Sahl, “a self-confessed egghead who rarely lays an egg.” Up on Russian Hill in the Fairmont Hotel’s Venetian Room, “entertainment of the caliber of Lena Horne, Sammy Davis, Jr., Nat “King” Cole, the dancing Champions, and the Mills Brothers” crooned for the swells, who enjoyed dancing to the Ernie Heckscher orchestra, “a fairly formidable institution in itself.”

But of all the pithy blurbs in Caen’s Guide, one stands out as a glimpse of the San Francisco that would be. No, it’s not an early sighting of a prototypical hippie in Golden Pate Park or a prescient exhibition of concert posters on the walls of the De Young—for the record, Caen tells his readers to keep an eye out for the “young lovers [who] float dreamily about in the small boats of Stow Lake” and the “works of Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, El Greco, Fra Angelico, Titian, Pieter de Hooch, and Goya” at what was then the “oldest and largest municipal art museum in the West.”

Fort Point, at the southern base of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Instead, Caen invites tourists to spend an evening at Finocchios, “the far-famed or ill-famed place—depending on your point of view—where ‘female impersonators’ go through their paces, alarmingly disguised in garish wigs, overflowing gowns, and comic-opera false bosoms, all designed to make your visiting maiden aunt from Anamosa, Ia., gasp in delighted disbelief (‘You mean they’re actually men?’). Some of the talent is quite good, and the productions show more imagination than you might expect. Finocchio, incidentally, means ‘fairy’ in Italian.”

And with that, Herb Caen introduces his readers to San Francisco’s nascent LGBTQ community, which, far more than the hippies, would come to define their city. After all, the struggle for civil rights has always been more compelling than the mere desire to let one’s freak flag fly, however much fun that might be.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Did the CIA's Experiments With Psychedelic Drugs Unwittingly Create the Grateful Dead?

Did the CIA's Experiments With Psychedelic Drugs Unwittingly Create the Grateful Dead?

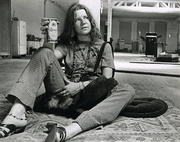

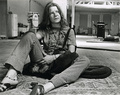

Behind the Scenes With Janis Joplin and Big Brother, Rehearsing for the Summer of Love

Behind the Scenes With Janis Joplin and Big Brother, Rehearsing for the Summer of Love Did the CIA's Experiments With Psychedelic Drugs Unwittingly Create the Grateful Dead?

Did the CIA's Experiments With Psychedelic Drugs Unwittingly Create the Grateful Dead? The Sissies, Hustlers, and Hair Fairies Whose Defiant Lives Paved the Way For Stonewall

The Sissies, Hustlers, and Hair Fairies Whose Defiant Lives Paved the Way For Stonewall BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of …

BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

How can I purchase the drawings from this guide? Id love to put some frames on them. —You can find copies on Amazon