It’s hard to take the ’70s seriously. The decade is usually reduced to a shag-carpeted, bell-bottomed punch line, parodied for its tacky consumer culture by shows like VH1’s “I Love the ’70s” or websites like Plaid Stallions. While the ’70s did include more than its share of garish colors and over-the-top looks, such bold moves were necessary to break free from a cautious, cookie-cutter society. Among other things, the 1970s gave people the freedom to dress however they chose, paving the way for flip-flops at the office.

The rigid social norms of the 1950s mostly collapsed during the ’60s, spawning a decade in which people felt free to express their individuality, even as they borrowed from a slew of historic references and ethnic influences. Contemporary trends like eco-chic, native craftwork, vintage revivalism, gender-bending androgyny, or DIY thrift-shop fashion all originally flourished during the 1970s. Above all, the decade was full of experimentation.

“What’s wrong with wearing a mechanic’s overalls or a factory worker’s uniform?”

When writers Dominic Lutyens and Kirsty Hislop met in London during the late 1980s, they bonded over their love of ’70s culture, listening to albums like Giorgio Moroder’s “From Here to Eternity” and poring over vintage copies of “Vogue.” After recognizing a general neglect of the 1970s’ creative output, they spent years researching the period’s overlooked innovations.

The result was 70s Style & Design, a book that’s particularly relevant as ’70s trends continue to influence fashion, from Louis Vuitton couture to bargain basement H&M. We spoke with Lutyens, an arts journalist for publications like “Vogue” and “The Observer,” to straighten out some misconceptions of the 1970s.

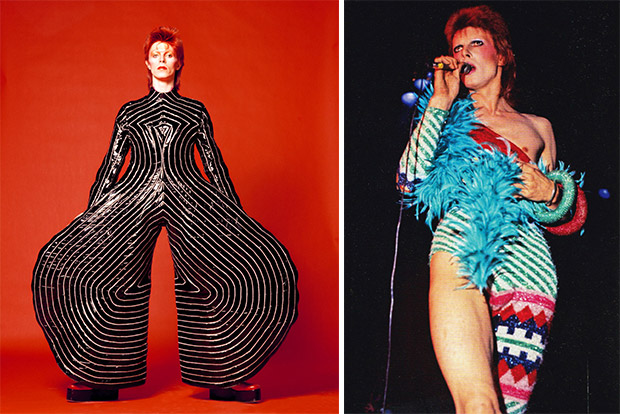

Top: Carol Brady played by Florence Henderson and David Bowie during his Ziggy Stardust phase. Bowie photo by Masayoshi Sukita. Above: Thea Cadabra’s “All Weather” heels epitomize the late ’70s pop influence.

Collectors Weekly: What’s surprising about ’70s style?

Lutyens: In terms of ‘70s fashion and design, four themes kept popping up again and again and again—pop, historic revivalism, back-to-nature, and the avant-garde.

The pop movement began in the 1960s as a reaction against cold modernism, which held sway throughout most of the 20th century, this Bauhaus idea of simplified design. In the ’60s, there was a backlash against this form of modernism where everything tended to be very functional and minimal and clean, this very pared-down aesthetic, whereas the emerging pop aesthetic was much more complicated. Pop made it okay to bring human elements into design through more sensual, ergonomic forms. There was more use of color, which had emotional connotations and also incorporated symbolism, something which the modernists had banished. And this flashy pop movement took off in the 1970s in an even bigger way, and lead into postmodernism.

Related: Summer in the Sixties

The Pointer Sisters, who loved wearing retro clothing, pose for the cover of their 1973 debut album with a variety of ethnic prints and patterns. Photo courtesy RB/Redferns.

Postmodernism allowed certain things that were banished by modernism to reemerge, like historical references to the past or wild patterns and color, things which modernists regarded as completely superfluous to design. And also just enjoyment in design; it could be fun again. Postmodernism was embraced by architects like Philip Johnson who created the famous AT&T building in New York, putting a Chippendale furniture top on it. Kirsty and I interviewed one of his assistants who said that basically AT&T’s chairman just got really bored flying over New York and seeing all of these boxes.

The ’70s pop movement was also influenced by earlier eras, like Art Deco, and the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s. There was a huge revival of styles looking back to the past. If you look at disco groups like Chic or the Pointer Sisters, they wore a lot of thrift-store clothes from the ’20s and ’30s. There were also lots of period films being made like “The Great Gatsby” that were set during those eras.

Mia Farrow and Robert Redford as seen in the 1974 version of “The Great Gatsby.”

The third theme we called “Supernature,” which was about the hippie movement going mainstream. In the very late ’60s you had all the hippies in the Haight-Ashbury area rebelling against straight society, and in the ’70s this movement became more environmentalist. For example, in 1970 you had the first national Earth Day which brought issues like pollution and diminishing resources into the public arena. And then with the 1973 oil crisis, suddenly people were thinking, “Well, why are we using all this oil anyway? Why are we dependent on the OPEC countries?” The oil shortages made the whole movement much more serious as well.

There was a lot of interesting architecture related to the environment that really flourished in the ’70s, like Paolo Soleri’s “Arcosanti” project in the Arizona desert which is still continuing today. But there was a commercial side to this as well, and fashion started looking back to nature. The style was very much influenced by the homesteaders or the early pioneers of America. These styles were seen in Jessica McClintock’s label Gunne Sax, and also the television program “The Little House on the Prairie.”

Left, the cast of NBC’s “Little House on the Prairie” which debuted in 1974. Right, a 1973 campaign for designer Laura Ashley played on imagery from the western frontier.

And in contrast, during the ’70s you also had this urban avant-garde culture, where people were actually rejecting this “back-to-nature” movement, which they thought wasn’t authentic as the hippies believed it to be. Basically, there was this other huge cult of artifice and kitsch and camp. You have people like John Waters or Andy Warhol or the Cockettes, all these avant-garde people who really advocated artifice through things like wearing drag, through kitsch, through androgyny. Things like “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.”

Collectors Weekly: Why do you think the ’70s are so frequently mocked?

Lutyens: Well, it’s often seen as really tacky. It’s often associated with polyester flares and clunky platforms and plastic furniture and orange or bland beige. It’s seen as ridiculous, but also quite fun. So today you have all these ’70s parties with people dressed up in flares and fake Afros. Those parties just never seem to die out.

“The Brady Bunch” epitomized an early ’70s cliche of plaid and polyester.

This image is actually very limited; it was a very small part of the ’70s. And in fact, what I would actually call a “Brady Bunch” or “Partridge Family” look, was very early ’70s, yet people seem to think the ’70s was a whole decade of this style. The bright plastic furniture and the lava lamps and all that had already existed in the ’60s.

It’s a quite comic element that’s appealing because it’s larger than life, but it’s a bit of caricature really. I think it’s quite easy to digest because it’s a very one-dimensional kind of image.

Collectors Weekly: Who were some of the true innovators at the time?

Lutyens: In the ’60s French fashion really dominated, and everyone moved to Paris, but in the ’70s it became much more international with the influence of other groups on mainstream fashion, like black culture and Japanese culture. There was much more variety.

This late ’70s poster for the ultra-pop fashion label Fiorucci embodies the New Wave disco look. Courtesy Edwin Co., Ltd.

Fiorucci was an Italian label that was very popular in Europe and America, with a huge store in New York. In the ’70s, it was like you were either in Studio 54 or Fiorucci. There was another really important fashion label in Britain called Biba that was housed in various boutiques in London, and finally in a huge Art Deco building. Biba’s style was very influenced by 1920s Hollywood, with this dark, silent-movie makeup.

Antony Price is a great example of a designer who was really atypical for the ’70s because his look was very tailored. He designed all the stage costumes for the English band Roxy Music. His clothes were very ’40s-influenced and quite sharp, while we typically think of the ’70s as floaty and loose.

Japanese designers also really started to make their mark in the ’70s. Kansai Yamamoto did all of David Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust” costumes. But a lot of the names that we take for granted now, like Gianni Versace, Giorgio Armani, Sonia Rykiel, Karl Lagerfeld, Missoni, all started out in the ’70s and they’re still famous today.

Two looks created for David Bowie by the fashion designer Kansai Yamamoto in the 1970s. Left photo by Masayoshi Sukita and right photo courtesy Bill Orchard/Rex Features.

Collectors Weekly: What prompted such radical changes in popular fashion?

Lutyens: One reason was that people in the West were becoming increasingly affluent, and this gave young people the confidence to question their parents’ values. Because they had money, they could be more independent. Society was also becoming much more liberal as well because you had things like the legalization of homosexuality and the legalization of divorce. People were allowed to be themselves more without being judged by other people.

Then the three main minority movements—feminism, black civil rights, and gay liberation—all these minorities had been marginalized until the late ’60s. In the ’70s they began to assert themselves more and become more visible. So their style became more visible, and it influenced mainstream fashion.

A good example of this is the black civil rights activist Angela Davis who wore an Afro hairdo, which was completely natural, because she felt that she didn’t want to conform to white Western ideas of what black people should look like. This would not have happened without the political movement that was going on, so politics was influencing style.

Left, the cover of the 1972 book “Angela: Portrait of a Revolutionary” shows Davis’ distinctive Afro hairdo. Right, Carol Troy’s “Cheap Chic,” published in 1975, made thrift shopping mainstream.

Gay men could wear drag quite openly, especially in places like San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood, and others like David Bowie dressed with quite androgynous style even though they were straight. Women no longer felt the pressure to look conventionally feminine, so they wore trousers more, they wore their hair in more masculine hairstyles, particularly in the punk scene. All of these things resulted in fashion becoming much more varied.

Collectors Weekly: Did any of these styles stick around?

Costumes for “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” featured a blend of punk, glam, and drag camp, seen here on original cast member Tim Curry. Photo by Mick Rock.

Lutyens: The hippie fashions of the ’70s certainly left their mark, and can definitely still be felt. And it’s also part of the fashion lexicon now for women to wear suits or ties because one of the major trends of the ’70s was for women to incorporate men’s clothing, like jackets, shirts, ties, and trousers. That look was popularized by Woody Allen’s 1977 film “Annie Hall,” where Diane Keaton wore ties, men’s jackets, and so on.

There was also a best-selling American book called “Cheap Chic,” which came out in 1975 and basically said, “What’s wrong with going to an army surplus store or wearing a mechanic’s overalls or a factory worker’s uniform?” The book made things like the jumpsuit really stylish, and they’re still popular now.

Another legacy of the ’70s is this informality. In the ’60s you have to remember that people wouldn’t go out without wearing a hat or gloves and those kinds of accessories, and now that’s not necessary. Certain key pieces of clothing like denim jeans, which were popular across all generation in the ’70s, and are still very popular today. I think that we almost take that informality for granted now.

Collectors Weekly: Why do you think ’70s trends are suddenly being revived?

Lutyens: Some of it is pure nostalgia: Designers like Stella McCartney and Phoebe Philo say that they’re inspired by their mothers’ wardrobe. Some ’70s styles like long skirts and looser clothing are also more flattering on women in their ’30s and ’40s, and I think that age makes up a large part of the fashion-buying public. Another element is all the vibrant color and pattern in ’70s clothing, which has a modern, sensual appeal. It’s quite fun to wear vibrantly colored clothes and patterns.

The 1974 book “Native Funk & Flash: An Emerging Folk Art” by Alexandra Jacopetti focused on the ways individuals were incorporating ethnic craftwork and customizing their own clothing.

Collectors Weekly: What’s the deal with polyester?

Lutyens: To be honest with you, I wouldn’t really wear it. I hate it. Even in the ’70s it was a cheap High Street thing to wear. You wouldn’t get very sophisticated people wearing polyester at the time. But one reason I think polyester was really big is that in the ’60s people were in love with the idea of technology. So anything new, modern, practical, people loved it.

This whole idea of technology wasn’t so new to people by the ’70s, and they could take it or leave it. I think a big part of the ’70s was this return to something more romantic, and technology wasn’t the be-all and end-all anymore.

This Mexican photoshoot featuring Biba clothing showcases Deco-retro and glam rock influences. Photo by John Bishop.

Collectors Weekly: Do you think clothing today has lost that wildness of the ’70s ?

Lutyens: I suppose people are a lot more reserved today in what they wear, and I think the same thing applies to interiors and homes. The ’70s very much encouraged this whole notion of individuality. There was nothing wrong with expressing yourself, and along with that went some quite wacky clothing.

People are much more self-conscious now and they don’t want to look weird or different. They just want to look sexy and attractive, and that usually means fitting some kind of mold. In a way I would also say that in a recession the people are generally a bit more scared, a bit less confident.

Collectors Weekly: How did the ’70s affect our environmental outlook?

Lutyens: In 1969, the “New York Times” reported that concern for the environment was on its way to eclipsing student discontent over the war in Vietnam. The following year, 20 million Americans took to the streets in celebration of the first national Earth Day, raising awareness about pollution, pesticides, urban sprawl, the dangers of nuclear power and the population explosion.

Generally, America led the way in the environmentalist movement. A lot of people fled the cities to establish all these communes, and I think this is perhaps easier to do in a country as big as America—it’s easier for you to escape.

The final 1974 issue of “The Whole Earth Catalog,” a magazine that provided a variety of do-it-yourself building resources.

There was a huge boom in eco-architecture during the early ’70s, partly in the wake of Buckminster Fuller who had created his geodesic domes, these self-build glass structures that allowed you to look out directly onto nature. There was also a very important magazine called “The Whole Earth Catalog” which basically gave you all this information about how to build your own house far from the city.

By 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter had taken measures to help Americans with the cost of installing solar hardware in their homes. And in 1979 he practiced what he preached by equipping the White House with a solar water-heating system.

Another aspect of this architecture was that the buildings looked really natural. They weren’t boxes; they were in really organic shapes and they were often made of local, natural materials. They were also often made by all the people who lived in the building or community, everyone would be involved in the construction.

It wasn’t a purely rural phenomenon: In the United States, this was happening all over the place, for example, in Manhattan, during the mid-1970s this tenant-owner cooperative created the city’s first solar collectors to heat water. Months later these were followed by wind generators to provide the building with electricity. So a lot of architecture from this time looked at ways to cut down on the use of fossil fuels.

Initiated in 1970, Paolo Soleri’s “Arcosanti” project created a utopian-style community housed in buildings explicitly connected with the natural landscape.

Collectors Weekly: What’s the best lesson you’ve learned from the ’70s?

Lutyens: I think that it’s more of an attitude, really. When we were researching our book, people were really helpful and generous, especially with their time. And I feel that now people aren’t the same. They want to know “What’s in it for me?” or “How can I gain from this situation?” I think people were much less materialistic. Kirsty and I both thought, wow, I want to be more like these people. I also think there was this feeling that you could be creative, and that it wasn’t naff or anything—just to be experimental was a good thing.

But I think it also has a lot to do with economics: Rents were much cheaper, and people didn’t have all these burdens of financial responsibility, which made it more playful because people had time to do things outside of work and paying their bills. New York or San Francisco are now really expensive compared to the ’70s. The Cockettes, for example, were able to use their welfare checks to buy clothes and do all these experimental things.

For a photoshoot in 2009, musician Devendra Banhart and his bandmates dressed to imitate the legendary Cockettes, a gender-bending performance group from the ’70s. Photo by Lauren Dukoff.

Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free

Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free

Is Our Retro Obsession Ruining Everything?

Is Our Retro Obsession Ruining Everything? Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free

Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free Lady Gaga, Innovator or Copycat? We Dissect “Born This Way”

Lady Gaga, Innovator or Copycat? We Dissect “Born This Way” 1970s Mens ClothingBy the early 1970s, young people taking a stand against America’s political…

1970s Mens ClothingBy the early 1970s, young people taking a stand against America’s political… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I was around in the 70s and we had to wear those clothes then, but for Heaven’s sake, I’d never ever wear those fashions again. They were hideous. The 70s was the worst decade for fashion in the late 20th Century, followed closely by the 60s.

Carol Brady played by Florence Henderson is an image three, four, or five times removed from what was going on in the streets, in the air that we breathed. The sixties were the impetus for the seventies. Our RAGS MAGAZINE in 1970 somehow evolved into the book by me and Caterine Milinaire, CHEAP CHIC, in 1975 and then 1978. And now “HIPPY CHIC” is the show opening at Boston’s MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS in July. See you there?

I love 70s fashion – my favourite designer of all time is probably Kenzo Takada — especially his ‘jungle jap’ label from the 70s.

Some cool stuff from the 70s. Music for instance. Leisure suits were not one of the cool things.

The 1970s were also a golden age for fundamental physics. http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/magazine/physicstoday/news/the-dayside/a-quiet-revolution-a-dayside-post

Geez, my mother made me a teal polyester pant suit when I was little. Even mom hated it. And the nighties from that era, were soft on the outside, smooth nylon on the outside and sewn with clear plastic, or so it seemed. Fair enough I bet the designer clothes were….ok.

All these web sites about 70s fashion only show the commercial side of 1970s clothing. For the most part, if you were young in the 70s it was about jeans, flannel shirts, T-shirts and cotton clothing from India, which was HUGE back then. Only really geeky types wore polyester disco wear and Brady bunch crap. I know because I was a teenager in the 1970s.

Yes, 70’s clothes were both low key and flashy, depending if you are working or partying. I was a teen too in the 70’s. I loved all the clothes and was a big thrift store nut – which is why I have some cool things to post on CW now. I wish I had kept my platform shoes.

The 70s were great. It’s boring now…everyone looks like everyone else… cars, houses and clothes look alike now. I would take the Brady look over now. It was colorful and fun…fun is the one thing that is lost in this age. I miss the colors, the cars and split level houses….not to mention real rock stars.

No doubt The 70s were great. You just wins heart by sharing it

Interesting article. I feel I missed out on the 70’s, but my parents were 70’s teens and had me young. My mom introduced me to vintage stores in high school in the early 90’s, as well as when some 70’s looks were coming back in the newer stores. We would share certain clothes. That’s the last time I can recall fashion being so free and expressive – though nothing close to the 70’s experimentation. I can see now a lot more of her fashion spirit and where it comes from. I’m grateful for the influence.

Polyester was popular because it didn’t need to be ironed. Ironing was probably never a popular chore, but as more women entered the workforce, polyester became a real time saver.

The 1974 book “Native Funk & Flash: An Emerging Folk Art” by Alexandra Jacopetti mentioned the artistic Bauer family. The parents went on to have their folk art creations shown in museums and one of their daughters became an heirloom handbag designer…@Maya Moon Designs. I met the family in the late 80s early 90s and they were lovely people with a lovely fairy tale home. Maya was always fashion forward even as a teen in the workplace.

“Because they had money, they could be more independent” tells the whole story. That whole scene happened because we weren’t running scared. Rent and food were incredibly cheap, and there was always a place to crash or hang out. People in general were able to be more relaxed and social, if they liked – and we did like. If playing around with fashion or furniture was your thing, nothing stopped you. I feel like everything is such a struggle for young people now….