Before souvenirs became synonymous with cheap, mass-produced tchotchkes and T-shirts, they were more akin to holy relics—a lock of hair cut from the head of a former president, a chunk of carved wood taken from the construction of an impressive building. These artifacts acted as primary documents, proof of a holder’s connection to a celebrated person, place, or event. “I was here; I touched this,” early souvenirs seem to say.

“They’re just rocks and pieces of wood. Without a story, they’re lost.”

Taking objects as mementos of places traveled or sights seen has been a human custom for hundreds of years. During the 15th century, cabinets of curiosities first gained prominence as travelers curated collections of exotic objects, antiques, and natural specimens. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was fashionable for wealthy young Europeans to undertake a journey known as the “Grand Tour,” visiting historic sites in cities like Paris, Rome, and Athens, and collecting jewelry, art, and local crafts to bring home as souvenirs. Across the pond, in the ever-expanding United States of America, locations typically became worthy of souvenirs because of their natural beauty or their role in the young country’s development.

When Smithsonian curator William L. Bird organized the 2013 exhibition “Souvenir Nation: Relics, Keepsakes, and Curios,” he uncovered mementos at the National Museum of American History completely unrecognizable to modern tourists. Many of the objects Bird included in the show and its accompanying book had never been exhibited, and upon first glance, might have been mistaken for pieces of trash. Ranging from a fragment of Plymouth Rock to a Confederate punch bowl to spoils from the Mexican-American war, these objects helped shape America’s remembrance of its own past.

Without amateur souvenir collectors and relic hunters, the Smithsonian Institution might never have become the renowned network of museums that it is today. “You really can’t have a national museum,” says Bird, “until you have a nation of people collecting things, people who at least have that concept in their head—the collecting ideal. As low-tech and modest as some of these objects may be, they’re stand-ins for this larger purpose of national memory.” So what makes a good souvenir? According to Bird, each one is a “little bit of memory” that’s physically transportable. “Once you have it,” Bird says, “you can figuratively transport yourself back to that moment in time.”

We recently spoke with Bird about the evolution of souvenir collecting and the great stories these bits of historic detritus have to tell. (All images courtesy the National Museum of American History.)

Top: A piece of the Washington Monument’s 1848 cornerstone was accidentally broken off during construction and collected by philanthropist Joseph Meredith Toner. Above: Early visitors to Plymouth Rock were given hammers to chip off souvenirs for themselves, like the fragment at left, but the stone was protected in a gated memorial by 1880, as shown on the postcard at right. (Photos by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

Collectors Weekly: Have Americans always collected souvenirs?

William L. Bird: Yes, I think that’s true. You can make a distinction between a souvenir and a relic, but the overarching concept is something that has an actual connection to a person or place.

In the Smithsonian collection circumscribed by the exhibition and book, these objects were initially relics, and then they became classified as souvenirs. It took me a while to realize the operative search words were “relic” and “relic hunter.” Increasingly, into the late 19th century, those words often appeared in the same paragraphs with “vandal” and “vandalism.” For example, during the Lincoln presidency, there was a woman so obsessed with the White House that she cut pieces of fabric from the drapes—these big, heavy, ornate velveteen draperies. She was escorted from the grounds and told to not come back. It’s hard to imagine anybody doing that today.

One episode in the book was taken from Mark Twain’s travels overseas, when he was in Egypt and heard the tinkling sound of tack hammers as people chipped away at the monuments. There are other examples of people shooting at column capitals with guns to get fragments from them. Even at the time, people were commenting that this was over the line, that they were destroying these landmarks.

Collectors Weekly: How did the Smithsonian decide to save these ordinary-looking objects?

Abby Knight McLane’s curio cabinet included a piece of a cedar doorpost from a government building in St. Augustine, Florida; a stone from Mount Pony, Virginia; oak from a bog near Killarney, Ireland; a small white stone from Pompeii, Italy; and a round metal piece from the HMS Great Britain. (Photo by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

Bird: The items at the Smithsonian were cataloged when they arrived, meaning they were given numbers, tagged, and that sort of thing. Every time something came into the collection, it was accepted with a letter or a chain of correspondence verifying its importance and the reasons the museum decided to accession it. The deeper you look, the more significant these items become, and you get a sense of the kinds of things that they chose to save. The museum staff was often relying on secondary accounts, but if it was taken at face value by the museum when it first arrived, I generally accepted their records.

Some objects made up small collections, like Abby Knight McLane’s carefully labelled curio cabinet that included a rock resembling an arrowhead from the top of a mountain near Culpeper, Virginia, and a piece of wood from a house in St. Augustine, Florida. One of the items I like most is a piece of the Bastille, just a little metal cube. The significance is all in the story because the object itself is so unremarkable in its outward appearance. It makes you wonder about the objects that were accepted but never labeled or described. They’re just rocks and pieces of wood. Without a story, they’re lost.

Collectors Weekly: Did you discover any items in the collection that were incorrectly identified?

After the French Revolution led to the Bastille’s destruction in 1789, chunks like this were sold as a souvenirs. (Photo by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

Bird: There were a couple of items like that, which I took out of the book. Sometimes the repeated telling of the tale became embellished, or perhaps there was just a misunderstanding. The person writing those original notes didn’t have the Internet to look up certain facts and figure out, “Oh no, wait, it couldn’t be.”

For example, we have this little compass, maybe about an inch and a quarter in diameter, that came from the manuscript collection at the Library of Congress. Their Manuscript Division would routinely purge their files of any three-dimensional museum-type materials, and a Smithsonian curator would go over and collect them. One came back with the story of this compass, supposedly used by John Breckinridge, the former vice president of the United States, to escape from Texas to Mexico at the end of the Civil War.

I thought, well, that’s a great story: This little crackerjack compass was used to escape the Confederacy? But a quick search revealed that he had left the country from Florida by boat.

Collectors Weekly: What role did Mount Vernon play in the development of the souvenir market?

Bird: Our collection is filled with little bits and pieces of Mount Vernon. It seemed to be the mission of every tourist to make a pilgrimage there, even when Washington was alive, and anything related to Washington was at the center of their relic collections. There’s no dearth of accounts from travelers making their way to Mount Vernon, just showing up unannounced, and being welcomed by the father of the country or by Martha after his death.

It was difficult to get there until the beginning of a regularly scheduled steam excursion that would leave from Washington, D.C., stop in Alexandria to pick up more people, and finally land at Mount Vernon. In the late 19th century, they put in a trolley line.

The people that ran the estate had to be on their toes when visitors were circulating through the house and the grounds. Taking pieces of Washington’s house, slices of chairs, or things like that was always prohibited, but they did sell souvenirs, like objects made of wood from the estate that was carved into canes and that sort of thing. Mount Vernon’s caretakers began to shift their attention to the greenhouse, where visitors could buy plants or other items that could be produced at the estate.

Left, a small wooden plaque made by James Crutchett at Mount Vernon in 1852. Right, an 1879 ivy cutting supplied a makeshift souvenir from Washington’s estate. (Photos by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

For that reason, I think wood was the preferred material, so you had souvenirs like a compass embedded in a buckeye or nutshell or something like that. Among the earliest and most desirable items were these little pieces of Washington’s mahogany coffins. [Due to deterioration, the wooden exterior of Washington’s coffin was replaced multiple times after his death, with small pieces distributed to friends and acquaintances.] There are also pieces of wood that were turned into mementos by James Crutchett who bought wood from John Augustine Washington, George Washington’s great-grandnephew and the caretaker of Mount Vernon.

We even have a piece of egg-and-dart style molding from Mount Vernon, an acorn-sized bit of molding with a cut nail in it. It looks as though someone just pulled it off of something, but now we can’t identify where exactly it was taken from. In terms of a category of collectible relics, Mount Vernon just excels.

A piece of Washington’s mahogany coffin given to Leverett Saltonstall by John Augustine Washington, George Washington’s great-grandnephew. (Photo by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

Collectors Weekly: Did manufactured souvenirs help stem this type of vandalism?

Bird: It quickly became apparent that people would continue to collect pieces of monuments as they found them unless they were offered another form of souvenir. More often than not, they would be happy with a picture of it, like a postcard, for example. As printing technology improved, the cards became more detailed, colorful, and exact. Buying mass-produced souvenirs eventually became an acceptable substitute, rather than chiseling away a piece of Mount Vernon.

One of my favorite transition objects is this little toy compass embedded into a buckeye, a compass inside a nut, basically. The buckeye is allegedly from Mount Vernon, but the compass is from nowhere in particular. Put them together, and they probably appeared for sale in a shop at Mount Vernon or in Washington, D.C.

This compass embedded in a Mount Vernon buckeye was one of the Washington-related souvenirs sold in the late 19th century. (Photo by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

I was reading something recently that claimed the earliest American souvenirs were buttons with shanks on the back, little commemorative metal buttons that said “Long live the president,” which were introduced around the time of Washington’s inauguration in 1789. But as soon as you say that’s the earliest example, someone will find one earlier.

It’s really hard to pin down exactly when they started selling manufactured souvenirs. To research this, I followed the development of the souvenir trade in Washington, D.C. I located a really great article from the late 19th century that listed a kind of a compendium of places that you should go when visiting D.C., mostly next to government buildings. There was a stand in the Capitol building, and one in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, where they sold little buildings made of macerated currency. Oddly enough, the Smithsonian wasn’t even on the list.

The smartest business people located their shops close to monuments and government buildings if they weren’t concessionaires actually within a building. If you took a cheap penknife and sold it in the Capitol building, the value escalated because then people could say, “I bought this at the Capitol.”

The market really developed after the advent of colorful lithography and picture postcards, which comes around the 1890s. By this time, there began to be a large enough souvenir trade in Washington that it was commented upon and articles were published about it. Certainly by the first decade of the 20th century, the streets of the city have these remembrance shops or souvenir stands. Germany cornered the market for a lot of these items, and they could make them inexpensively; for example, the earliest color postcards were all made in Germany. Then the technology was exported and brought over here, and then there were other companies like the Detroit Publishing Company or Curt Teich & Company in Chicago.

The Bureau of Printing and Engraving was a popular Washington, D.C., tourist destination, as seen on this 1904 postcard.

Collectors Weekly: How did collector John Varden influence the founding of our National Museum?

Bird: John Varden is a far more interesting and colorful character than I think he’s been given credit for. Varden used his personal collection to establish a Washington city museum in a house he rented for that purpose. He was in the theater world and built a lot of his own displays, providing a neat bridge between theatrical stagecraft and museum design. Some of the curiosities came from his actor friends, and others were items he purchased.

It wasn’t necessarily a money-making venture, since he was still employed in the stagecraft business, but he built up a subscriber base of people who paid to support the museum. Varden also traveled to New Orleans a couple of times to winter there, and purchased items all up and down the Mississippi River on these trips. He had account books in which he described and cataloged the objects he acquired.

When he was just about to turn this museum into a full-time business, the federal government deposited its relics in the Patent Office gallery, a couple of blocks from where Varden’s museum was. So Varden quickly made the decision to sell his collection to the new National Institute and become a paid employee there. Varden made certain exhibits himself, like the framed collection called “Hair of the Presidents and Persons of Distinction,” and one of the coach panels from George Washington’s carriage that had been given to him by a Washington descendant.

Varden officially joined the Smithsonian, with its scientific and biological collections, in 1858. But the Smithsonian’s directors didn’t really care about historical relics, which stayed at the Patent Office until 1883. Varden is often referred to as the museum’s first curator and its first janitor in the same breath. He’s the guy who would mothball all the collections while the Institution’s scientists were on vacation in the summer.

Two objects from Varden’s National Museum that eventually made their way to the Smithsonian: Left, a painted panel from George Washington’s coach, and right, a framed collection titled “Hair of the Presidents” from 1855. (Photos by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

Collectors Weekly: Did the Smithsonian’s scientific staff look down on historic relics?

Bird: They weren’t really interested in history. Joseph Henry, the museum’s first secretary, never considered the Smithsonian’s mission to be educational. In fact, he went out of his way to declare that the objectives of the Smithsonian were not educational in his annual report to Congress. Anything that took away from their goal of research, he had no use for. He had no appreciation that you could obtain knowledge from collections of any kind—scientific, historical, or otherwise.

The Smithsonian got into the museum business through its second secretary, Spencer Baird, who was the assistant under Henry. Baird understood that new knowledge could come from collections, but he was focused on biological and botanical objects, not necessarily historic. Oddly enough, Baird’s family owned a napkin from Napoleon that was given to his mother-in-law, but Baird never gave it to the museum. It was a later bequest of his daughter.

Collectors Weekly: How did the Smithsonian’s goals shift to include a historic museum?

Bird: Baird was instrumental in accepting the remnants of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. To house these artifacts, the Smithsonian constructed a cross-shaped building next to the Castle called the Arts and Industry Building. The architecture was quite amazing—this low-budget building with maximum display and floor space—and it didn’t take the staff long to figure out they should take the historical relics that were lingering at the Patent Office and install them in the north hall of this building.

“It became a place people thought of as the nation’s attic.”

Momentum started to build, and eventually the rest of the Patent Office collection was brought over. One of the last items to be moved was Benjamin Franklin’s press, which was in the old Patent Office gallery until 1883. The historic artifacts that people think of today as the building blocks of our National Museum collection were really the last things to arrive.

When it was complete, you would come in from the mall and walk under this arch that said “National Museum.” You’d see George Washington’s uniform, his household effects, and on and on. The next route, to the right of Washington’s, started with Abraham Lincoln’s effects, and so on. The three remaining halls were reserved for anthropology, botany, or any kind of ethnographic exhibit. When you went through it, it was very easy to get lost, since each of the halls looked the same except for what was actually in it. It became a place people thought of as the nation’s attic. By the end of the century, they had relics from the Spanish American war and were on the way to building a great military-history collection. They had all kinds of Civil War memorabilia—Grant and Lee’s chairs, the surrender table, the flag of truce, these kinds of things.

Collectors Weekly: What’s your favorite souvenir relic in the collection?

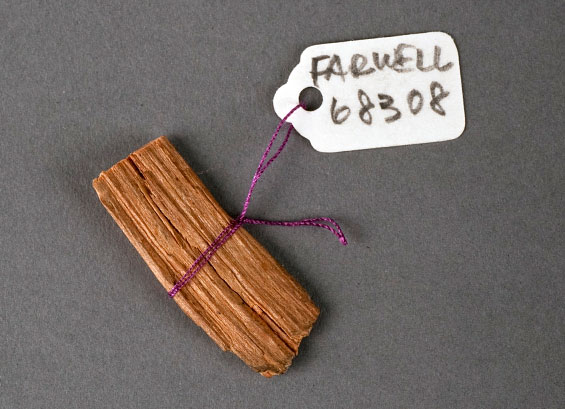

Bird: That’s got to be the little piece of a railroad tie with a great story. An 8-year-old boy named Hart Farwell was traveling with his mother from their home in the Midwest in 1869, three weeks after Leland Stanford laid the ceremonial Golden Spike. They got off the train in Promontory Summit, Utah, and Farwell cut a chip of what he thought to be the last tie laid for the Transcontinental Railroad.

He kept it his whole life, and grew up to become this telephone executive in Illinois. So he sends the chip with a letter to the Smithsonian. There was a special last tie made from California laurel with pre-bored holes for the spikes, so they could take out the laurel tie and replace it with a pine tie just like all of the millions of other railroad ties.

This piece of a railroad tie from Promontory, Utah, was saved by Hart Farwell in 1869. (Photo by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

People then began whittling the pine tie, and two different travel writers at the time estimated that tourists stopping to take a sample of the so-called “last tie” whittled away one entire tie per week. Farwell was whittling in the third week, so he was probably working on the third tie.

When the donation and letter came in, it caused the secretary of the Smithsonian to wonder, “Gee, whatever happened to the Golden Spike? Is that something that we should have?” So the secretary writes a letter to a friend who’s the chairman of the board of the Union Pacific Railroad, and his friend sends a company magazine that explains the whole history of the ceremony in Promontory. He quickly disabuses the secretary of the idea that the Smithsonian is ever going to get anything close to a Golden Spike.

In fact, he just rubs it in and says, “You know, when they cast the Golden Spike, there was gold left over from the casting that was made into little commemorative lapel-pin spikes.” He says, “The next time I see you, I’ll show you mine.” Not “I’m going to give you mine,” but “I’ll show it to you.”

This was all in the file for Farwell’s little wooden chip—the functional equivalent of getting a moon rock from the moon landing. It was a huge story in its day and caused this man to keep this chip his whole life and then send it to the Smithsonian. Then it caused the secretary to wonder about the original Golden Spike. That little piece of wood is as close as the Smithsonian has ever gotten to collecting one of the real gold spikes, like the ones at the California State Railroad Museum or the Cantor Museum at Stanford University.

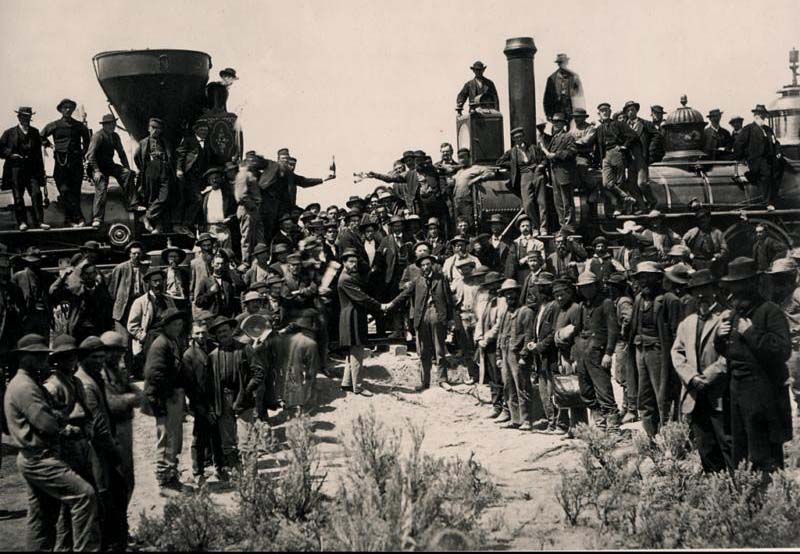

A photograph of the Golden Spike ceremony following the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad route in Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869.

Collectors Weekly: Does the Smithsonian accept donations of contemporary souvenirs today?

One of the museum’s more recent relics is this piece of the Berlin wall, broken off during the celebration of Germany’s reunification in 1989. (Photo by Richard W. Strauss, Smithsonian Institution.)

Bird: Well, sure. I will look at almost anything anybody offers. Now we prefer to make email contact and ask people to take a picture of their item. But to tell you the truth, it’s not the kind of donation that typically comes up. I don’t think people think of souvenirs as anything other than a personal memento.

Part of my job, however, is to collect new items from significant events. We collect material from presidential campaigns. We start off in Iowa at the caucus, we go to New Hampshire for the primary, and then we see how the field shakes out and go out on the campaign trail, usually starting at the conventions of the major parties, collecting the things that people make, wear, carry, and hold up. They don’t have any great monetary value, but when you get it all together at the end of the year, this collection really doesn’t exist any other place.

So we do collect that type of thing, but we don’t call them relics anymore. We ennoble them, and call them “historical artifacts.” What’s a souvenir? It’s all in the intent of the person collecting it—are you documenting it or trying to remember it, or both?

(To learn more, get the “Souvenir Nation” book or visit the exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s Castle on the National Mall, Washington, D.C., through the January 28, 2015.)

From Ruby Slippers to Kermit the Frog: Pop Culture Artifacts at the Smithsonian

From Ruby Slippers to Kermit the Frog: Pop Culture Artifacts at the Smithsonian

What America Can Learn From Berlin's Struggle to Face Its Violent Past

What America Can Learn From Berlin's Struggle to Face Its Violent Past From Ruby Slippers to Kermit the Frog: Pop Culture Artifacts at the Smithsonian

From Ruby Slippers to Kermit the Frog: Pop Culture Artifacts at the Smithsonian Skeletons in Our Closets: Will the Private Market for Dinosaur Bones Destroy Us All?

Skeletons in Our Closets: Will the Private Market for Dinosaur Bones Destroy Us All? SouvenirsFrom a piece of a NASA space shuttle to a pressed coin sold at Disneyland, …

SouvenirsFrom a piece of a NASA space shuttle to a pressed coin sold at Disneyland, … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.