The multicolored, drug-soaked, psychedelic aesthetic of the mid-1960s has never been more popular, or misunderstood. In March, “Mad Men” time-traveled from the cocktail cool of Mid-Century Modern, circa 1962, to that dope-smoke-filled hothouse known as Pop, circa 1966. And in April, Donovan, whose “Mellow Yellow” was released that same year, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Not bad for a guy who was singing a song that many people have long assumed was about getting high off dried banana peels. In fact, it may have been about vibrators, which makes it about the “sex,” rather than the “drugs,” in “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.”

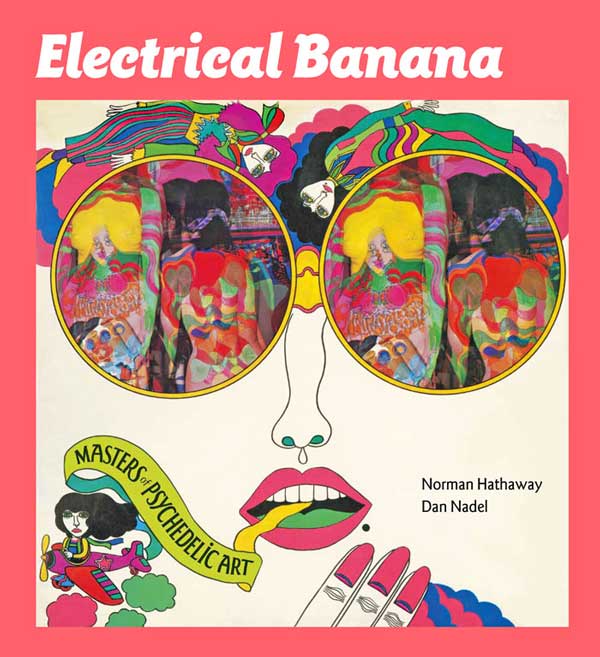

This spring also saw the publication of a new book titled “Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art,” by Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel. Featuring an introductory interview by Hathaway with Paul McCartney, the 208-page paperback shines a bright spotlight on psychedelic artists from Europe, Australia, and Japan, some of whom were never comfortable with the term that came to define them. On Sunday April 29, 2012, the authors and graphic artist Gary Panter will be at MoMA PS1 in New York to talk about the book and show a few film clips provided by some of the artists.

“In the ’60s, I was scorned as a psychedelic artist, especially when seen in the company of Tim Leary.”

Taking its name from a line in Donovan’s famous tune (McCartney played bass on the recording), “Electrical Banana” features interviews with, and artwork by, seven highly influential artists, such as the late Heinz Edelmann, who conceived the landscapes and characters in the animated feature “Yellow Submarine,” even though he describes himself in the book as being “allergic” to many of the most common tropes of psychedelia. Then there’s Tadanori Yokoo, whose collages took their inspiration, in part, anyway, from traditional kimonos. Believe it or not, some of these artists didn’t even take drugs.

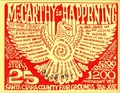

“The book originally had about three or four other artists in it,” says Hathaway, “but a couple people kind of fell by the wayside. It wasn’t until later that I noticed that there wasn’t a single American in the book, which I ended up being kind of happy about. Usually when people think of psychedelic art, they primarily think of the Fillmore stuff and not a lot else. It’s always Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin, and Victor Moscoso, but there was a lot going on outside of San Francisco, too.”

Heinz Edelmann’s artwork for The Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” included this sequence that accompanied the song “Nowhere Man.”

The book begins with Heinz Edelmann, a Czech-born graphic designer who was living in Dusseldorf when he got the call to work on “Yellow Submarine,” an animated feature for The Beatles that, much to his chagrin, became his legacy. After all, this was a man who was influenced by artists as diverse as Picasso, Saul Steinberg, and Ben Shahn, and here he was, being asked to draw characters for a film that did not even have a script.

To hear Edelmann tell it, “Yellow Submarine” was a colossally frustrating experience, so much so that he almost didn’t see it through. The breaking point came on one Friday night. “I was full of hate at everybody,” he tells Nadel, “and thought, ‘Well, I’ll resign, but I’m not going out with a whimper, I’ll go out with a bang.’ That is when I did the Meanies, and the Meanies were originally supposed to be Communists. I always wanted the Meanies to win, but I didn’t get my way.”

Martin Sharp’s homage to Bob Dylan, “Blowin’ in the Mind,” was silkscreened on foil in 1966.

If Edelmann was a reluctant participant in the psychedelic aesthetic (“I don’t like the smell of incense,” he deadpans), the late Australian artist Martin Sharp was an active one, who admired the San Francisco rock-poster artists and cartoonist Robert Crumb in particular. Sharp, who lived in London for a few years before moving back to Australia, even contributed lyrics for “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” which was eventually recorded by Eric Clapton’s band Cream.

“I didn’t know who he was,” Sharp tells Hathaway of his first encounter with Clapton. “I learned Eric was a musician, so I told him I’d just written a song. He replied he’d just written some music. So I wrote the lyrics down for him.” The song appears on Cream’s second album, “Disraeli Gears,” whose 1967 cover was drawn freehand by Sharp at its actual size.

Paul McCartney wrote “Hey Jude” and other hits on a piano painted by the design group Binder, Edwards & Vaughn.

Other artists were more like art directors and the set decorators for the pop-music scene. Dudley Edwards was a member of the London design group Binder, Edwards & Vaughn, which made a business of custom-painting dressers, chairs, and other pieces of furniture, treating them, essentially, like three-dimensional canvases. One of the group’s first non-furniture pieces was a 1960 Buick convertible, which eventually was used by the Kinks on an album cover. That led to a commission for Paul McCartney in 1967.

“I remember I first saw a photo of their painted car in the ‘Sunday Times Magazine’ and thought it was really cool,” recalls McCartney in his interview with Hathaway. “So I got in touch with them and asked the guys if we could have a meeting. We did, and I told them ‘I’ve got a little piano I’d like you to decorate in that same style.’ And at first they were a little bit reluctant to do anything, but I persuaded them. So they measured it all up, took the panel dimensions, and worked up some designs. Then they painted it and did a lovely job. It became my psychedelic piano, which I wrote a lot of songs on, including ‘Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band,’ ‘Fixing A Hole,’ and ‘Hey Jude.’ It’s in its rightful place in my music room in London.”

Marijke Dunham was hired to create outfits and paint the guitars for Cream’s first U.S. tour.

If Edwards was the guy who customized the fixtures enjoyed by Londoners, including city walls that were transformed into traffic-stopping murals, Marijke Dunham and her group, The Fool, did all that (a fireplace for George Harrison, a piano for John Lennon), and also clothed them.

In a weird way, Dunham’s psychedelic inspirations were most traditionally psychedelic. “Drugs were a big part of it,” she admits to Hathaway flatly, arguing that the aesthetic, “has a bad name due to that. I mean Van Gogh painted his strange paintings and there’s been no mention of drugs, but drugs definitely had an influence as far as the cause was concerned, with the strange moving lines, definitely … and since I’m not ashamed about it I don’t have to hide it. That’s where it comes from.”

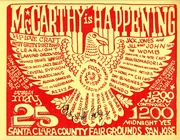

Keiichi Tanaami was not a fan of the Monkees, but a gig was a gig.

Meanwhile, in Japan, Keiichi Tanaami was harnessing the disturbing, traumatic childhood memories of the fires in Tokyo during World War II for saccharine album covers for The Monkees, whom he never cared for. He was also producing graphics for magazines, but it was a 1968 visit to New York, where he met Andy Warhol and saw the Jefferson Airplane, for whom he’d do an album cover, that really opened his eyes.

“I visited America in 1968,” he recalls, “at a time when the country was full of turmoil—the assassinations, the protests. I saw underground comics then, like Robert Crumb. I also discovered pornographic newspapers. Both were extremely shocking for me.” That led to projects for “Playboy,” one of which was a feature called “Wonder Girl” for the Japanese version of the magazine. “I was very influenced by ‘Superman’ and ‘Wonder Woman’ comic books,” he tells Hathaway. “I found them in stores close to my university. I loved ‘Wonder Woman’ the most.”

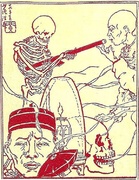

Tadanori Yokoo chafed at the cold modernism that grew out of graphics produced for the Japanese Olympic Games in 1964.

Another artist from Tokyo, Tadanori Yokoo, was making dense posters characterized by rich colors and a deep sense of perspective. As Hathaway says of Yokoo, he “was affected, but not absorbed by the Sixties. He passed through it, impacted it, and moved on.”

In “Electrical Banana,” Yokoo recalls commissions that were rejected (a cover for “Time” magazine of the prime minister of Japan being strangled by an American flag necktie), as well as the influences he was rebelling against (the “true path of modernism” that came out of the 1964 Olympics). And he also remembers the one that got away.

“Bob Dylan once took a bunch of my work, collaged it together, and his manager brought it to me and asked me to make something similar to it for a cover, and it was awful. It was the day before I had to leave with my family on holiday to Italy, so I had to refuse. But I wish I’d kept the sketch—it was Dylan drawing my images.”

This 1962 painting by Mati Klarwein became an album cover for the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia in 1971.

Rounding out Hathaway’s and Nadel’s collection of seven artists is the late Mati Klarwein, who was born in Hamburg, Germany, but fled with his family to Jerusalem at a very young age at the onset of World War II. In the 1960s, Klarwein was commissioned by Jackie Kennedy to paint a portrait of her late husband, and he also did portraits of such living luminaries as Leonard Bernstein and Brigitte Bardot. Somewhere along the line, his surreal paintings became album covers for Santana (“Abraxas”), Jerry Garcia (“Hooteroll?”), and Miles Davis (“Bitches Brew”).

Of all the artists in “Electrical Banana,” Klarwein is the hardest to pin down, as he described it some years ago. “During the Abstract Expressionist epidemic of the Fifties, I was dismissed as a latent Surrealist illustrator. In the Sixties, when the Pop Art revolution swept the globe with its tidal waves of whimsical garbage, I was scorned as a psychedelic artist – especially when seen in the company of Tim Leary – too close to LSD for the straight culture-vultures of Madison Avenue. In the Seventies, when Conceptualism was the magic word (what else is there, anyway?) and a work of art was called a ‘piece,’ I was haughtily snubbed as an old-fashioned easel painter from Montmartre. It’s only in the Eighties, now that conservative senility has entrenched itself in the marrow of Western culture, and good old-fashioned easel painting is being resuscitated as high-funk nostalgia, that the art-mart world is beginning to treat me with a little respect for the first time.”

(Images courtesy Norman Hathaway)

How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict

How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict

Psychedelic Poster Pioneer Wes Wilson on The Beatles, Doors, and Bill Graham

Psychedelic Poster Pioneer Wes Wilson on The Beatles, Doors, and Bill Graham How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict

How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict Blueprint for the Occupy Movement? Read the Protest Manifestos of the 1960s

Blueprint for the Occupy Movement? Read the Protest Manifestos of the 1960s Psych RecordsPsych is a broad term referring to a genre of psychedelic vinyl albums and …

Psych RecordsPsych is a broad term referring to a genre of psychedelic vinyl albums and … Peter MaxThe bright, flamboyant artwork of Peter Max serves as a visual shorthand fo…

Peter MaxThe bright, flamboyant artwork of Peter Max serves as a visual shorthand fo… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

FAROUT MAN! thanks for turnin me on!

Norman Hathaway was still actively worked as an art since from mid 1960s up to now… very great article!