At the end of 1843, when most good Victorians were commemorating the season by dutifully drafting hand-written letters to their colleagues, friends, and relatives, Henry Cole was working out a way to avoid all this sentimental drudgery. As a prominent public servant and supporter of the arts with a busy social calendar, Cole’s address book was filled to the brim, and writing lengthy notes to all those esteemed contacts was getting more time-consuming every year.

“Christmas was as much a holiday as a holy day.”

Cole needed a way to send personalized greetings without the personal investment required by a standard letter—something memorable, cheery, and to the point. He was well aware that postcards were cheap and easy to send: Having worked as an assistant to inventor Rowland Hill, Cole had helped reform Britain’s mail system with the use of prepaid adhesive stamps, called the Uniform Penny Post for its flat-rate pricing regardless of destination. So he asked a friend and painter named John Callcott Horsley to illustrate his vision of the mass-produced holiday spirit.

Cole’s design didn’t feature a pious image of the Virgin and Child, but rather a jolly family raising a toast toward the card’s recipient, flanked by silhouetted scenes of people helping the poor. The card included blank “To” and “From” fields, along with a printed note reading, “A Merry Christmas and A Happy New Year to You.” Though he gave the religious celebration lip service with this text, Cole’s card clearly depicted a secular interpretation of the holiday. In addition to sending his own, Cole printed and sold hundreds of these cards for one shilling each. The War on Christmas had begun.

Top: A silly Victorian Christmas card, circa 1880s. Via the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Above: Henry Cole’s design for the first-known holiday card from 1843.

Eventually, the center of holiday-card production spread to the United States, where the medium took on a life of its own. “In 1875, when Louis Prang first started selling holiday cards in the United States, they were definitely not religious,” points out Mary Savig, curator of manuscripts at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. “There were a lot of floral motifs, children, and sleigh scenes, which might say Merry Christmas, Happy New Years, or Seasons Greetings. Many people have used cards to say ‘Happy Holidays’ well before this War on Christmas.”

Anthropomorphized Christmas pudding was a popular subject for Victorian holiday cards. Via the Laura Seddon collection at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Today, those who claim we’re steadily erasing the religion’s presence in our annual holiday celebrations decry the mere failure to mention the name of the Christian fable surrounding Jesus’ birth. In reality, diverse celebrations—including many secular traditions—have long been a part of America’s winter traditions, from lighting menorahs to hanging stockings on the mantle. Looking at the designs of holiday cards from the 19th century to the present, it’s clear that Americans have always sent season’s greetings free from Christian overtones.

In George Buday’s quintessential study of the topic from 1954, The History of the Christmas Card, only one chapter is devoted to religious cards, falling among others on subjects like comical, sentimental, political, and wartime cards. As Buday explains, the custom of exchanging tokens of good luck at this time of year dates back to ancient times.

“In fact, we should have to go back to pre-Christian times, when the festival was not yet celebrated as the anniversary of the Birth of Christ, but as a feast for the winter solstice,” Buday writes. “People then celebrated the reawakening of Nature, anticipating the coming of spring and longer hours of daylight. They associated with it their various forms of beliefs in the victory of life over death, light over darkness and green verdure over snow and ice.”

Buday points out that many traditions still associated with the winter season evolved from pre-Christian celebrations: “Mummers and their plays, mistletoe and the kiss beneath it, the yule log and its kindling, the wassailing of fruit trees, a number of traditional dishes, such as the boar’s head and mince-pie, all have their origin in these ancient rites.”

Louis Prang was known for making some of the most elaborate (and expensive) Christmas cards, like this example from the 1880s. Via Paper With a Past.

When Henry Cole’s colorful holiday cards reached the members of his influential London circle, and beyond, the trend was quickly embraced by many of the British elite. By the 1850s, even Queen Victoria was sending illustrated Christmas cards (she and her husband, Prince Albert, also helped popularize other traditions like Christmas tree decorating).

British publishers such as Marcus Ward & Co., Thomas De La Rue, and Raphael Tuck & Son took the Christmas card mainstream, employing their own recognizable artists and printing hundreds of die-stamped designs each year. Across the pond, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Louis Prang launched the American holiday-card industry with small placards featuring flowers, birds, and a few words of text.

In the late 19th century, most holiday cards were flat postcards, rather than folded greeting cards. As demand grew, the industry took its cues from the already popular Valentine’s Day postcards, sometimes even producing cards that could be reused during the winter by adding a thematic scrap of paper bearing a Christmas or New Year greeting.

Children’s book illustrator Kate Greenaway designed this card entitled “The Merry Dance When Dinner’s Done” in 1881.

Early Christmas cards often featured imagery of seasonal flora like holly, ivy, and mistletoe; holiday dances or pastimes like ice skating; traditional meals like roast turkey or spherical Christmas pudding; comical designs with puns and illustrations of faces caught mid-laugh; or scenes of childhood. From the outset, holiday cards also went beyond conventional tropes to include images of celebrities, fictional characters, and technological novelties like the bicycle, telephone, airship, or automobile.

“The Victorians had some really strange ideas about what served as an appropriate Christmas greeting,” says Bo Wreden, who recently organized an exhibition of holiday cards for the Book Club of California. “They liked to send out cards with dead birds on them, robins in particular, which related to ancient customs and legends. There’s a famous quotation from the Venerable Bede about a sparrow flying through the hall of a castle while the nobility is celebrating Christmas: The moment from when it enters until it flies out is very brief, a metaphor for how quickly our lives pass.” Apparently, killing a wren or robin was once a good-luck ritual performed in late December, and during the late 19th century, cards featuring the bodies of these birds were sent to offer good luck in the New Year.

Most mass-produced designs were smaller than modern cards, and sometimes printed on paper cut like lace, or actual fabrics like silk and satin, and adorned with silk fringe and tassels. Folded holiday cards began appearing in the 1880s, but didn’t overtake Christmas postcards until the first decades of the 20th century.

While card publishers sometimes hired established artists, like illustrator Kate Greenaway, their work was constrained by the need to sell as many cards as possible. But once the ritual of sending holiday cards was established, many creative folks made their own. Mary Savig has closely investigated the Archives of American Art’s collection of personalized holiday cards, which were created, sent, and received by artists themselves, then saved as part of their correspondence files. In 2012, she published a selection of these in the book Handmade Holiday Cards from 20th-Century Artists.

Harry and Jeannette Haenigsen sent this card with a faux stock-market graph to Alfred Frueh around 1929. Courtesy the Archives of American Art.

Many of the objects Savig found at the Archives represent atypical, one-of-a-kind designs, with hardly a Santa Claus or Christmas tree in sight. In part, Savig attributes the artists’ diverse interpretations of the medium to the variety of commercial holiday cards available at any given time. “With the rise of individualism in the United States, there came to be a card for everybody, whether you wanted to send peace doves or bells or a Hanukkah-themed card,” Savig says. “Artists often emulated those commercial trends as well: some were religious, humorous, or location-specific, like joking about warm weather with Santa Claus on the beach.”

Even when working with cliché subjects, artists used these cards as an opportunity to showcase their unique aesthetic sensibilities. “This was a chance to put their best selves out there, like a creative calling card, to wish people a happy new year, but also send them a little sample of their work,” Savig says. “I think it was a clever way to brand themselves.” Accordingly, many of the letters are almost unrecognizable as holiday cards, using abstract imagery or breaking free from the paper-card form.

This inventive card made from a paperclip, rubber bands, and cardboard was sent from artist Kay Sage to Eleanor Howland Bunce in 1962. Courtesy the Archives of American Art.

“Andrew Bucci, who made beautiful handmade cards that he sent to a wide network, kept a really funny example from an artist named Dan Flavin, made from a sticker and a stamp. Bucci used to joke that Flavin was really lazy, which is funny because Flavin was just a minimalist who worked with fluorescent lights and basic materials. I love that people were finding a way to make these in their own artistic idiom—even if it was a bit of a trope, like the star of Bethlehem—I’m sure this made it really delightful for people to receive.”

This hand-colored print by Loïs Mailou Jones was sent to her dealer, Martin Birnbaum, circa 1937. Courtesy the Archives of American Art.

Some of the most surprising examples Savig discovered are cards that reveal personal details about the artists that are absent from their professional work. “One of my favorite cards is by Loïs Mailou Jones, an African American artist who moved to Paris to study because it was a more racially tolerant city at the time,” Savig explains. “She was from Boston, and sent a holiday card to her dealer that features a Boston Terrier and says ‘Bonne Année’ in French. One of her descendents told me she had always owned Boston Terriers and was a huge fan of them. She didn’t paint these dogs in her work, but I thought it was so sweet that in this card had a little Boston Terrier on it so you could get a sense of her personality.”

“Another favorite is by Robert Smithson, a land artist known for Spiral Jetty and other earth works. Apparently, he was a big fan of cinematic thrillers. He took advertising work from the movie ‘Village of the Damned’ and made a Christmas card from it using photomechanical reproduction. I was in touch with his widow, Nancy Holt, and asked her about some cards he had received from other artists. She said, ‘Oh, you know he sent these really weird cards.’ I was like, ‘No, I didn’t know that. I haven’t seen them.’ So she sent me one via email, and I screamed when I opened it, because I was expecting a peaceful, earthy kind of card. It has a picture of these really creepy children on it, and he superimposed lightning bolts over their eyes and wrote ‘Christmas is for Children.’”

The Wredens’ 1993 holiday card was printed by the Feathered Serpent Press based on an image in Frank Leslie’s Boys’ and Girls’ Weekly from 1879. Courtesy Bo Wreden.

As the exhibition at the Book Club of California shows, professional artists weren’t the only ones who created their own Christmas cards: Bo Wreden curated this selection of personalized cards from those sent and saved by his parents, Bill and Byra Wreden. In the late 1930s, soon after they started selling antiquarian books from their home in Burlingame, California, the Wredens began commissioning custom letterpress holiday cards, like many in the bibliophile community.

“In the course of buying and selling older books related to the history of California and the West, my father would pull out text that amused or appealed to him, and have a local press design a card around the content,” Wreden explains. “He always liked to find curious and unusual things, and, in fact, he had a whole file of things he set aside with the idea that they might be used on a card.” After his father’s death, Wreden continued to help his mother create such unique cards drawing from historical texts.

The Wredens’ cards included quotations and imagery from a variety of sources, ranging from the collections of arts museums to a farmer’s almanac to an 1868 column in the “Daily Morning Chronicle.” Their love of irreverent material is made obvious by the “Chronicle” excerpt, titled “The Toot Horn Nuisance,” which details an obnoxious holiday trend involving boys roaming the streets with irritating toy instruments (not unlike the modern vuvuzela). “My parents’ cards tended to be secular in their nature, though not exclusively. I think they had a tendency to take a Victorian-English approach to Christmas: It was as much a holiday as a holy day.”

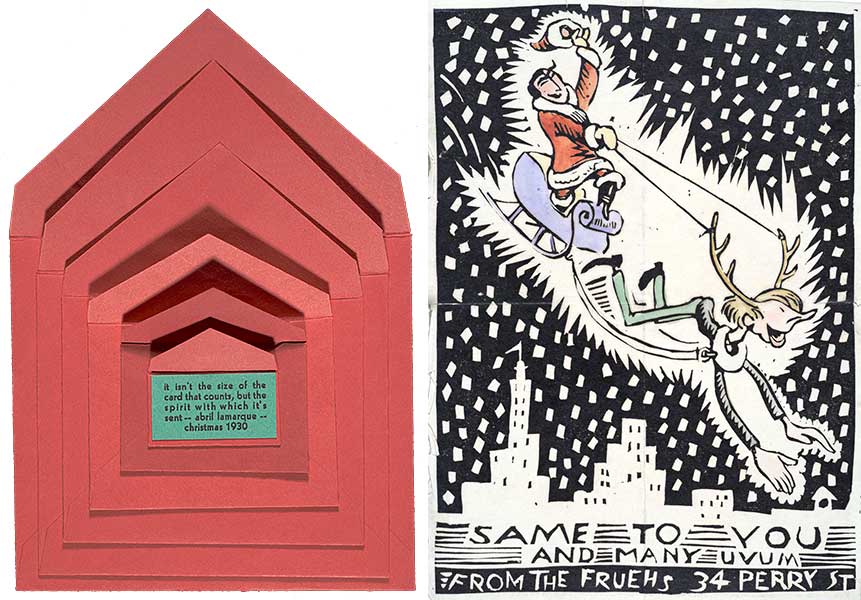

Left, an unsent card by artist Abril Lamarque, designed to fit inside six paper envelopes. Right, Alfred Frueh sent this hand-colored print, depicting himself as a reindeer and his wife Giuliette as Santa, to Wood and Adelaide Lawson Gaylor around 1920. Courtesy the Archives of American Art.

Despite their outward differences, the sentiments of secular holiday cards often encompass the same symbolism found in the season’s religious parables, urging recipients to behave kindly toward those who have less and to hold out hope in times of darkness. Throughout the last century and a half, these are the types of universal values that holiday cards have attempted to elevate, whether made by the millions or handcrafted for a single recipient.

“Holiday cards have always been this physical trace of the relationship between two people, a reminder that you took the time to think of them and send this note during the holidays, and with the rise of email, I think they’ve become even more special,” Savig says. “They’ve shared cards with so many subjects—from flowers to Santa Claus to landscapes to religious imagery—but one of the most popular images has always been peace doves.” Whether or not the intent is political, at this time of year, many people choose to send a message of peace.

This screen-printed card by Gordon Kensler was sent to Kathleen Blackshear and Ethel Spears around 1960. Courtesy the Archives of American Art.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

You'd Better Watch Out: Krampus Is Coming to Town

You'd Better Watch Out: Krampus Is Coming to Town

Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up?

Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up? You'd Better Watch Out: Krampus Is Coming to Town

You'd Better Watch Out: Krampus Is Coming to Town Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You Christmas CardsChristmas greeting cards were a byproduct of the cheap postal service in Vi…

Christmas CardsChristmas greeting cards were a byproduct of the cheap postal service in Vi… ChristmasCollectible Christmas items range from antique hand-crafted pieces like blo…

ChristmasCollectible Christmas items range from antique hand-crafted pieces like blo… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Another wonderful article with enlightening twists and perspectives on a (too often) mindless custom so easily taken for granted!