When humans first developed the wheel, there were surely some naysayers who bemoaned the jobs it would eliminate, the unsafe speeds of newfangled carts, or the damage wheels would do to our most cherished relationships. Today, we’re all too familiar with the knee-jerk reactions that accompany every advance in modern technology: Self-driving cars will steal jobs from professional drivers, or social-networking apps will eliminate face-to-face interaction with other humans. The overarching fear is that any popular technology will fundamentally alter a previously satisfying, well-balanced existence and destroy the society we’ve worked so hard to build.

“We forget that technologies are actually reflections of our values and our desires, and they co-create one another.”

Although our apprehension about new tech seems to grow increasingly dire, fear has gone hand in hand with technological advancements throughout history. “It’s interesting to see the lament of each generation overwhelmed by the next new tool,” technology forecaster Paul Saffo said in a 2006 interview. “I can show you passages from scholars of Germany in the 1480s lamenting the fact that they are overloaded with all this stuff to read because of the printing press.”

In hindsight, the eventual explosion of printed matter and subsequent spread of literacy allowed people to seek out information relevant to their lives, forming tighter communities with those who shared their values and interests. Despite clear evidence that we use technology to augment our closest relationships, the technophobic have consistently argued that innovative devices—whether a newspaper, a telegram, or an iPhone—isolate people from the world around them and prevent meaningful social connection.

“You can go back to the printing press and find all this rhetoric about the fear that people would no longer need to remember things,” says Coye Cheshire, associate professor at the School of Information at U.C. Berkeley. “Now, you hear people talking about that with regard to the Internet. What’s old is new again.” Deep down, we’re not afraid of newfangled technology as much as we’re afraid of giving in to our selfish desires, becoming mindless blobs glued to digital screens, forever gulping unhealthy snacks.

Top: A French postcard from around 1900 predicts videophone technology of the year 2000. Above: Before cell phones, humans had plenty of other media to distract them during the daily commute. This photo of passengers reading in a subway car was taken by Stanley Kubrick in 1946. Via the Museum of the City of New York.

However, looking back at past innovations, it’s clear that this is partly because humans have used technology to satisfy the same impulses throughout history. As Vaughan Bell wrote for Slate, “From a historical perspective, what strikes home is not the evolution of these social concerns, but their similarity from one century to the next, to the point where they arrive anew with little having changed except the label.”

Take, for example, the desire for more convenient food options: The ability to order a meal via smartphone and have it quickly cooked and delivered is merely the latest iteration of advancements like dumbwaiters, vending machines, automats, and drive-thrus. In fact, you can trace these innovations (and complaints of lazy, antisocial behavior) back to the creation of the first modern restaurants, which likely appeared in France during the 18th century.

If a concern for sloth seems ridiculous to 21st-century sensibilities, consider the position of an infamous group of British textile workers during the early 19th century. Known as the Luddites, they protested the adoption of new looms and stocking frames by factory managers who were attempting to lower wages and remove hard-won labor rights. Though they’ve since gotten a bad rap for irrationally fearing technology, the Luddite approach was actually a bit more nuanced. Having worked closely with these machines, they were well aware of their benefits. Luddites weren’t against new machinery per se, but they wanted to protect certain human values, like physical safety and job security, in the face of advancing production standards.

Ford Madox Brown’s 1888 mural at the Manchester Town Hall in Manchester, England, depicts John Kay being smuggled out of his home as a Luddite mob attempts to destroy his famous fly shuttle.

While it’s great to critique technology and analyze its impacts on our lives, the fears that accompany new devices are often misplaced. When first introduced, radio, television, and video games were all predicted to destroy the American family, but it’s the invention and evolution of the telephone that offers the most illuminating parallel for critics of today’s networked digital devices. Indeed, many of the complaints about smartphones, ranging from etiquette issues to health risks, were also heard when the telephone began its march to ubiquity.

Early telephone advertising focused on the professional uses for telephones, seen in this Stromberg-Carlson ad from 1905. Via Wikimedia Commons.

As the telephone made inroads into private homes at the end of the 19th century, there was widespread criticism about the ways its presence would disrupt the social order. Initially, though, manufacturers marketed the device specifically for business or emergency purposes. In part, this was because the emerging industry was closely associated with the telegraph, whose usage was restricted to short messages conveying strictly professional information. Blind to their obvious misogyny, journalists and telecommunication leaders denigrated conversational phone calls as examples of frivolous female behavior, and it wasn’t until the 1920s that the telephone industry began advertising—and profiting from—the social benefits of its products.

In 1909, sociologist Charles Horton Cooley wrote a typical critique of the telephone’s influence in his book Social Organization: A Study of the Larger Mind. “In our own life the intimacy of the neighborhood has been broken up by the growth of an intricate mesh of wider contacts which leaves us strangers to people who live in the same house. And even in the country the same principle is at work, though less obviously, diminishing our economic and spiritual community with our neighbors.”

In fact, the invention served many existing needs beyond its business-related functions, particularly helping to cement social bonds in an era when families and communities were physically spreading further apart. In his 1992 book on the adoption of the telephone, America Calling, Claude Fischer writes that “conversation, even gossip, is an important social process, serving to sustain social networks and build communities.”

Fischer’s analysis of three California communities during the initial expansion of telephone lines found that phones actually increased the strength of ties to both immediate and distant social networks. “The net trend was in the direction of greater attention to the outside world. Yet, rather than indicating a displacement of local interest, these changes suggest a simultaneous augmentation of local and extra-local activities,” Fischer explains. Technology allowed people to be more social than ever before.

This postcard from 1912 suggested that Americans had become overly reliant on the telephone, even when speaking to someone in the same room.

The telephone quickly became instrumental for speaking with loved ones in other cities, for making travel arrangements, for verifying shop hours and inventory, for planning parties. “As much as people adapt their lives to the changed circumstances created by new technology, they also adapt that technology to their lives,” Fischer writes. “The telephone did not radically alter American ways of life; rather, Americans used it to more vigorously pursue their characteristic ways of life.”

Today, social media is the scourge that critics fear will undermine our face-to-face relationships. But in 2010, a Pew analysis found that frequent users of social media had more close relationships, were more politically engaged, and less socially isolated than the average American.

“So much of the dialogue just 15 years ago was about how the Internet was going to isolate us and make us mindless creatures just surfing the Web, people with their brains plugged into this machine, mindlessly looking at pages,” Cheshire says. “Internet addiction was imagined as people consuming all this information in a very isolating way. Few were considering the fact that this might actually involve communicating with people at a scale that is unimaginably larger than ever before.”

At a time when most of us are inundated with messaging apps and networking websites, Cheshire has to remind his students that a little over a decade ago, the category known as “social media” barely existed. “One of the human needs that is so critical to a lot of global information technologies, like the Internet, is our desire to be social,” Cheshire says. “It sounds so obvious, right?”

Though the concept of social media might be new, countless prior inventions served to improve our connection with others. While handwritten postcards and letters seem quaint today, when America’s postal network was first established, the ability to quickly and cheaply communicate via written text was thrilling. During the early 20th century, the heyday of America’s postal service, you could send and receive short notes via mail several times per day. How different is that from our adoption of e-mail and text messaging?

Children suffering from an unhealthy, anti-social “comic addiction,” seen in a 1938 photo by John Gutmann.

Cheshire points out that we often lose sight of the human impulse in new technologies, espousing technological determinism or the belief that innovations are acting upon us and shaping our desires without our control. “I think that’s where a lot of these fears come from—the belief that technology is somehow doing these things to us,” Cheshire says. “What is the telephone doing to us? What is the printing press doing to us? We forget that technologies are actually reflections of our values and our desires, and they co-create one another. That’s a much harder thing to conceptualize.”

“Internet addiction was imagined as people consuming all this information in a very isolating way.”

If it’s not the technology we fear, but rather the motivations behind it, perhaps it would be more fruitful to direct our criticism at the source of those attitudes. “In modern Western culture, we tend to value productivity, efficiency, and personalization,” Cheshire says. “Those are a few of the tendencies or values that are repeatedly reflected in new technology, particularly the information technologies that people tend to focus on.”

Relentless media attention on a few American tech hubs, like Silicon Valley, combined with the homogenous ranks at most tech companies, means that often these innovations are aligned with the needs of a very particular segment of the world (typically well-educated and well-paid white and Asian men). “We’re looking at a very limited scope of humans that are doing a lot of the value creation,” Cheshire says.

Fritz Lang’s 1927 film masterpiece, “Metropolis,” emphasized the dehumanizing potential of technology.

Outside the U.S., there are many common innovations that Americans haven’t embraced, such as those that reduce environmental impact. In Japan, showers and bathtubs often have digital temperature gauges to maintain the correct warmth before running the tap, while many toilets have a tank-mounted sink to wash hands, thus filling the bowl with greywater. In Israel and Germany, toilets typically utilize a dual-flushing device to use water more efficiently. These utilitarian devices are innovative solutions to modern problems, yet aren’t making headlines or being dissected on fan blogs. Considering that Americans are increasingly skeptical of science, it makes sense that we’d adopt communication technologies more quickly than environmental advancements.

If we gave scientific evidence more weight, we might see that the greater threat of technology is to our physical safety, rather than our social and mental health. This is a danger that’s hidden in plain sight, created by devices that have been normalized for generations, like automobiles and guns. Each of these innovations clearly has detrimental effects on public health in the United States: Studies show that car crashes remain the top killer of Americans under 35, while gun ownership makes you many times more likely to be shot and killed. But powerful players in these industries have used their financial success to keep public safety at bay, as repeated scandals have made abundantly clear.

We’d be much safer if cell phone use required cars to be stationary, as with this “drive-up telephone” from 1959.

In part, this is also because new technologies are adopted much faster than new social norms or legal regulations, particularly in the age of the Internet, and public health risks aren’t always apparent until after a new device is widely adopted. “The time between changing social norms and how fast technologies are iterated upon and adopted—we’re looking at different kinds of time scales,” Cheshire says. “It’s longer than what people typically think.”

Three decades after mobile phones were first introduced in the mid-1980s, we still don’t have a universal understanding of appropriate use, particularly with regards to the device’s health risks. Some municipalities and businesses restrict the use of phones in certain situations, like while driving or at live performances, but the inconsistencies continue to create confusion. “It’s not like anybody really thinks the cell phone is doing anything wrong, it’s that we don’t trust people to be safe or respectful, so we end up with all these rules and regulations,” Cheshire says.

While much of the research around cell-phone radiation has thus far been inconclusive, it’s clear that using a phone while driving is at least as dangerous as drunk driving and should be outlawed. Yet, as with automobiles and guns, once a technology is adopted widely, it’s very difficult for us to unlink the device’s benefits from its threats to our health. Texting while maneuvering a motor vehicle is really just the latest form of negligent driving, a problem we’ve been aware of, and selectively ignoring, for a hundred years. Just as obviously, guns make it easy to kill people, an act that has been frowned upon since the Gutenberg Bibles were printed, and likely long before that.

As Fischer sums it up, “…we might consider a technology, such as the telephone, not as a force impelling ‘modernity’ but as a tool modern people have used to various ends, including perhaps the maintenance, even enhancement, of past practices.” Which is one way of saying even tech can’t shake the status quo.

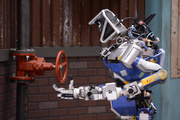

Someday, Robots May Save or Destroy Us All—For Now, They're Still Kinda Dumb

Someday, Robots May Save or Destroy Us All—For Now, They're Still Kinda Dumb

When Postcards Were the Social Network

When Postcards Were the Social Network Someday, Robots May Save or Destroy Us All—For Now, They're Still Kinda Dumb

Someday, Robots May Save or Destroy Us All—For Now, They're Still Kinda Dumb Murder Machines: Why Cars Will Kill 30,000 Americans This Year

Murder Machines: Why Cars Will Kill 30,000 Americans This Year Printing EquipmentMetal and wood type, the cabinets designed to hold these blocky letters and…

Printing EquipmentMetal and wood type, the cabinets designed to hold these blocky letters and… ComputersVintage computers aren't your typical collector's item, but some of the ear…

ComputersVintage computers aren't your typical collector's item, but some of the ear… TelephonesPeople started collecting phones shortly after Alexander Graham Bell patent…

TelephonesPeople started collecting phones shortly after Alexander Graham Bell patent… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I feel like you were talking directly to me. You have such a talent of connecting with your readers on a personal level. Certainly addressed some of my basic fears about today’s technology along with new perspectives to consider.

Great article, Hunter! I love it when a bright mind calls us on our innate fear of change—-which I chalk up to general survival wiring in the brain. The more awareness we have about this valuable and ancient built- in response within us, the better we are able to keep it from dominating our quality of life when erroneously triggered.

Thought provoking as usual Mr. O. I still think we will find devastating effects of the radiation from cell phones, which is one of the many reasons for hands free options. My cell phone has made it so easy to stay in touch on a regular basis with my kids who live in other states……many times texting throughout the day when an actual phone call is not always possible.

Excellent and insightful read.

It’s tempting to say even moronic idiots already knew this, but clearly quite a few folks do not know. LOL

First of all, it is preposterous to label someone who is critical or simply alert to the ironies and large failures and impositions that ‘technology’ imposes constantly and continually on the helpless consumer, as a “technophobe”. In fact, that rhetoric is completely characteristic of the large and smug population of “technophiles’; i.e. we conceived, design, made, and are selling it, therefore buy it, use it, get used to it, get rid of everything in your life to accommodate it or shut up!

But here’s the real problem. Its no good to go back in time and point out that people once objected to “techno solution invention X” and say, “see, it all worked out” the reason being is that it doesn’t take account of the disruptions at the time that “X” made its grand entrance into people’s lives. Most people live in the present, not in the future when “it all works out”.

I was especially reflecting on this yesterday after looking at a very expensive – and supposedly ‘revolutionary’ – new smart phone and camera. All very clever and I am not questioning that one bit. But whatever ‘change’ it brings is empty, its just a diversion. While the ‘technophile’ community doesn’t want to hear this and might even try to shout somebody (like me!) down for even suggesting that the social value meter for this advanced toy is about zero, I challenge them to definitively show how this ‘advance’ substantively contributes to society’s well-being or social progress.