Daile Kaplan talks about collecting 19th and 20th century photographs and photobooks. Daile is Vice President and Director of Photographs at Swann Auction Galleries in New York. She appears regularly as a photograph appraiser on the Antiques Roadshow, and is also featured in a series of short videos on fine photographs for Swann Galleries. Daile can be contacted at dkaplan@swanngalleries.com or via her website, www.popphotographica.com, which features items from her personal collection of pop photographica.

William Eggleston – William Eggleston’s Guide. First edition. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, (1976)

Swann, which is New York City’s oldest specialty auction house, was founded in the late 1940s as an antiquarian book house. In the mid-1970s, as popular interest in photography became more widespread, the specialist at that time realized that Swann should have sales that featured documentary and fine art photography as well as albums and photobooks. Until that time, auctions dedicated to photography and photo literature were unheard of. Therefore, Swann is considered a pioneer of the photographic literature market.

Today, books illustrated with photographs are garnering a lot of attention. In the past few years, there have been a number of excellent coffee table books about the genre by Martin Parr, Gerry Badger, and Andrew Roth. In addition, there are some very serious celebrity photobook collectors who have brought attention to the field. An underappreciated area of collecting for many years, it’s now firmly on the map.

In addition to photographic literature, Swann focuses on vintage and modern 19th- and 20th-century photographic prints. As artists transition to new digital technologies and examples of those prints appear in galleries, they are offered at auction. However, we are not yet selling many digital prints. We specialize in what are referred to as wet darkroom prints.

Even though photography is incredibly popular today, in the 19th century and even into the 1960s it was ridiculed as an art form. Needless to say, this didn’t stop artists from exploring photography as a form of self-expression. In the 1950s, important photographers like Robert Frank and William Klein were very focused on working with the book as a creative art form. After all, there were no commercial galleries or museums with regular photography programs, so we’re looking at a field where creative figures interested in making photographs were using the book or album to promote their work.

Photobooks are a great way for someone who’s interested in photography to begin collecting. Books are more affordable than vintage or modern prints, and they’re often designed with artistic integrity, making them very beautiful objects. If a photographer is successful and has a strong gallery representation, a trade monograph, which is published in thousands of copies, can sell out very quickly. Books may also be produced in a deluxe edition (that is, issued with an original signed photograph). Such examples tend to be more expensive and the edition size is smaller, say 50 to 75 copies. At Swann, we conduct four sales a year, and two of those feature photographic books.

Collectors Weekly: Are there certain photobooks and artists that collectors look for?

Kaplan: Photobooks by master photographers are always very desirable, including Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Man Ray, and Walker Evans, for example. All the masters of 20th-century photography are associated with particular monographs and books, and those books are considered works of art in their own right. Photographers like William Klein and Robert Frank were very actively engaged in not only making the pictures for their books but sequencing the pictures and designing the final object.

Robert Frank – The Americans. Introduction by Jack Kerouac. Illustrated with reproductions of Frank’s stunning photographs. First American edition. New York: Grove Press, Inc., (1959)

Swann’s catalogues, which are accessible on our website just before each auction, offer an international roster of photographers. For example, Japanese photographers in the 1960s and 1970s – Hosoe, Moriyama, and Ishimoto, who were influenced by Robert Frank – recognized the importance of the photobook and made remarkable contributions to the form.

Interestingly, the market for photobooks is distinct from that of fine art photographs. There are many photography collectors who are looking to purchase beautiful photographic prints to hang on their wall but who may not have any interest in illustrated books.

Regardless of the area of interest, there are always different levels of collectors. A collector first starting generally buys what they like. They’re usually not yet familiar with the literature in the field and they acquire what’s familiar to them, what they may have seen in a gallery or a museum. As they become more sophisticated, their tastes become more discerning. Maybe they start buying older material, such as salted paper prints, daguerrotypes or ambrotypes, or maybe they move from painting to photography. Today, the collector community is global and, for the most part, fairly sophisticated.

The Internet has changed the auction business completely. Today, instead of attending the auctions, many of our buyers are bidding via the Internet. They contact us for condition reports to obtain information about lots in a sale.

Collectors Weekly: Do you notice any trends among the collectors of 20th-century photography?

Kaplan: Today the marketplace reflects a representation of more diverse styles and idioms. An artist like Paul Graham, a British photographer who is noted for his pioneering color documentary-style photography in the early ’80s, is accepted as a fine art photographer. A noted fashion photographer like Richard Avedon, whose pictures regularly appeared in glamour magazines, sees his work is offered in fine art galleries and at auction.

Categories that used to segregate the different areas of photography – fashion, art, documentary, press photography, scientific documentation, social record – are falling away. We’re seeing less and less separation between what were once thought of as commercial photography, documentary photography, photojournalism, and fine art photography. Today they’re all considered equally important, and we sell works that would fall into any of those categories.

If we’d look at our October 2008 sale, for example, one of the top lots in that sale was an album of Brazilian photographs from the 1880s. Our sale also featured an Edward Weston photograph from the 1920s that sold for about $45,000 and a Danny Lyon civil rights portfolio that sold for $30,000.

Collectors Weekly: Who were some of the major photographers who dealt with social issues and civil rights?

Kaplan: I’ve written two books about Lewis Hine, a pioneer of social documentary photography in the early 20th century who photographed child labor, immigrants, and the First World War. Photographers associated with the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the 1930s – Ben Shahn, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans – are other major talents. They worked for the federal government, photographing conditions during the Depression so that all Americans could be aware of the devastation in the heartland. In the 1960s, Danny Lyon, James Kerales, Charles Moore, Bob Adelman, and Ernest Withers were active in the Civil Rights movement.

In terms of other 20th Century subjects, you have photographers like W. Eugene Smith, who went to Haiti to photograph asylum patients and traveled to Japan to photograph environmental conditions in Minamata. Collectors are interested in celebrity photographs, male nudes, female nudes, architecture, and the Western landscape. Photographers like Ansel Adams, who was an early environmentalist, really made people aware of the fragility and beauty of America’s parks.

Collectors Weekly: How do 20th-century photographs differ from 19th-century photographs?

Kaplan: Technique. Most 19th-century photographers worked with cumbersome large-format cameras that utilized glass negatives and produced albumen, or salted paper prints, which have a very distinctive patina to them. The first photographs are daguerreotypes, which are unique or one-of-a-kind photographs and are often referred to as hand or cased images. Other examples of cased images are ambrotypes and tintypes.

“I collect pop photographica, which are three-dimensional decorative and functional objects highlighted with photographs.”

20th-century photographs were for the most part monochromatic, utilizing the gelatin silver, or black and white, print. In the 1960s and ’70s, a new generation of photographers, including William Eggleston, Joel Sternfeld, and Stephen Shore, began to explore color as a medium for their photographs. Works by Paul Outerbridge, Jr., a major fashion and glamour photographer in the 1930s, have also been widely collected. He employed the color carbro technique, a very stable color format.

In terms of appearance, those are very obvious clues, and in terms of content, I don’t think anyone could mistake a 20th-century street photograph for a 19th-century street photograph. I think most people start with 20th-century because they start with what’s familiar to them.

Collectors Weekly: Where do you typically acquire photographs from?

Kaplan: Swann doesn’t acquire photographs or photobooks but acts an as an agent for consignors who may be private or institutional clients. We select and catalog the works, estimate the property, and promote each of the auctions.

Today the provenance of history of ownership as well as the condition of the photograph are extremely important. Collectors are very discerning about how the photograph has been handled over time.

On the other hand, photographs by Weegee, the great New York photojournalist, were used in newspapers and magazines and frequently manhandled by editors and engravers. In the 1930s and ’40s, there was no awareness of the economic value or importance of these prints. Therefore, when a Weegee print comes to market, if it’s torn or creased, that may not be perceived as a condition issue. However, there are very few photographers for which that would apply. Normally, condition is paramount.

Collectors Weekly: What about signatures or markings on the photographs?

Kaplan: As a collector, you need to do your homework. Talk with auction house specialists, gallerists, and curators about what to look for with regard to a photographer’s body of work. Some photographers never signed their photographs, but we know the sorts of paper as well as the style and format of their pictures. For example, it’s very uncommon to see a signed Alfred Stieglitz photograph, but Edward Weston almost always signed his pictures. André Kertesz would sign the back of his pictures, not the front, and he would note the negative date, not the date that the photographic print was actually made.

So there are a lot of considerations, and it can be complex. Obviously, if a photographer was known to have signed his or her prints, you want to find those examples. Since there wasn’t an international marketplace for photography until the 1970s, vintage prints were gifted by artists to friends and family members. In the 1970s, market conditions dictated that photographers be less casual.

Collectors Weekly: Can you talk more about 20th century photo processes?

Kaplan: The most popular is what was called the gelatin silver print, your black and white photograph. This was a very stable process, believed to last at least 100 years, that doesn’t have the fragility associated with some of the color techniques. If a gelatin silver print is well maintained – that is, not displayed by a window where artificial light is going to damage it or in an attic or bathroom where there’s too much moisture or changes in temperature – it will have a good, long lifespan.

Paul Outerbridge is probably the most famous photographer from the 1930s who worked in color, and then of course in the 1960s and ‘70s you see photographers like Richard Avedon and Irving Penn exploring color as an idiom. Of course, family members enjoyed taking snapshots (vernacular photographs) of their daily lives. Artists Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, and Joel Sternfeld photographed modern American life in transition. By the 1980s and ’90s, you begin to see photographers from the German school, like Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff, using color. It’s certainly expanded.

Collectors Weekly: Do collectors tend to display the images in their collections?

Kaplan: Sure. The important point is to frame your photographs archivally. Work with a professional framer who will use the appropriate materials. It’s best to use Plexiglass and make sure the frame is taped on the back to ensure that no dirt or pollutants migrate into the picture frame. Nielsen Bainbridge is a company that has developed state-of-the-art mounts, mattes, and wooden frames.

Collectors Weekly: Do you collect photographs personally?

Kaplan: I collect what I call pop photographica, an area I’ve pioneered consisting of three-dimensional decorative and functional objects highlighted with photographs. It’s material that relates to popular culture, folk art, African American art, and decorative arts. It casts a very wide net. I just fell in love with these wonderful objects a long time ago. I’ve curated shows about it and have been collecting for about 20 years. I have a very large collection – over a thousand objects – and I have an educational website devoted to this material.

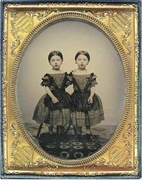

Many of the works are on display in my studio, and I have collector groups, college students, and graduate students come to see this material, which represents a different history of photography. Instead of emphasizing the framed photograph on the wall, pop photographica focuses on freestanding three-dimensional objects that you live with – a tintype photograph on a chair or a family portrait on your bracelet or earrings. It demonstrates how photography converges with popular culture.

It’s been interesting to see how many contemporary photographers are working in this mode, making scarves, furniture, and decorative objects from an artisanal perspective. They’re using their own pictures and working with craftspeople to make elegant jewelry and beautiful apparel highlighted with photographic images. Artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Vik Muniz, and Damien Hirst have all made multiples featuring photographic images.

Collectors Weekly: You’ve done some appraisals on Antiques Roadshow, as well.

Kaplan: Yes. My colleagues in the poster and works on papers departments and I appear on Antiques Roadshow. I’m the photograph specialist. Like many individuals in the field, my background is as a photographer. I became a curator and wrote about photography, and I have published two books about Lewis W. Hine – the first with Abbeville Press and the second with the Smithsonian. My third book, entitled Premiere Nudes, Albert Arthur Allen, was published by Twin Palms. My most recent book is about pop photographica and was published by the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Collectors Weekly: When someone brings you a photograph to appraise, what’s the first thing you look at?

Kaplan: I look at the condition of a photograph to see how well it’s been cared for, then content, signature, and paper stock. What is the image like? Is it in the right format? Is it the right paper stock for the period?

Photography was invented in 1839 and took the Western world by storm, but due to technological and cultural constraints, it didn’t appear in Asia and Africa until the 1860s to 1880s. We appraise photos from around the world – America, Europe, and Asia. Swann sells albums of Egyptian and North African photographs, but they’re largely from the 1870s through the 1890s. There’s a sophisticated market for hand-tinted Japanese photographs from the 1880s and 1890s. Pictures of Australia and New Zealand are also desirable, as well as those from subcontinental India. Russian and Chinese material is very rare.

Daguerreotypes are a very specialized area of collecting in which buyers are looking for occupational images, portraits of notable figures, or outdoor scenes. With regard to 20th-century images, interest in a particular photograph may be based on the beauty of the photographic prints in addition to its history: Was the photograph published in a book? Did it appear in a museum show? Was it previously in a prominent collection?

Collectors Weekly: What advice would you have for somebody who is new to collecting photographs?

Kaplan: It’s important to see as many exhibitions as you possibly can. Go to museums and galleries. Find an original photograph and then look at it in magazines and books. Educate your eye to the nuances of photography. Be sensitive to what you’re drawn to emotionally, that way you can begin to understand what you like. If you like flowers, buy pictures of flowers. It’s always a good idea to start collecting as an experiment in learning. It’s very important to educate yourself.

Very few collectors today are focused on a particular theme, though there are collectors who love nudes or the American landscape or fashion. Usually, people tend to be more diverse in subject matter. While there is a private collector with an impressive collection of Edward Weston’s vintage prints, he also collects other imagery.

Lately, there are serious collectors of photojournalism. These collectors usually focus on the iconic hard-hitting images, such as Nick Ut’s heart-wrenching image of the child running from a Napalm attack in the Vietnam War, or Robert Jackson’s photograph of Jack Ruby assassinating Lee Harvey Oswald.

Collectors Weekly: Tell us about some popular landscapes.

Kaplan: “Moonrise Over Hernandez” by Ansel Adams is one of the most popular photographs that we see at auction. This print is available in different formats or sizes that were printed during different periods in Adams’ career. In fact, a census indicates Adams made almost 2,000 copies of this photograph. However, whenever the image appears at auction, there’s competitive bidding on the lot. With regard to buyers of 19th century American landscape photographs, William Henry Jackson photographed Yellowstone and Carleton Watkins photographed Yosemite. We have collectors that just really love this material.

There have been numerous records for important 19th-century photographs at auction. The French photographer Gustav Le Gray, who created gorgeous marine landscapes in the south of France, have sold for more than $700,000. Photographs by Carleton Watkins have realized $500,000. Daguerrotypes have sold for $975,000. Most collectors don’t start by buying 19th-century photography, but ultimately they do recognize the beauty of it.

Collectors Weekly: Where do you see photography collecting going in the future with the introduction of digital images?

Kaplan: I think with the digital age there will be more of an appreciation of analog techniques and an understanding of the creative imagination and effort involved in making a photograph. After all, it wasn’t a point-and-shoot kind of thing. Until the digital age, photography was a hands-on medium. Working in the dark room is different from working on your computer.

Today, just about any contemporary artist is using digital technologies to make prints, but there aren’t any galleries that specialize in digital work. Commercial galleries sell both traditional and digital work.

(All images in this article courtesy Daile Kaplan and Swann Auction Galleries)

19th-Century Photographs, from Daguerreotypes to Cartes de Visites

19th-Century Photographs, from Daguerreotypes to Cartes de Visites

From Ambrotypes to Stereoviews, 150 Years of Photographs

From Ambrotypes to Stereoviews, 150 Years of Photographs 19th-Century Photographs, from Daguerreotypes to Cartes de Visites

19th-Century Photographs, from Daguerreotypes to Cartes de Visites How My Pal Pete Got On Antiques Roadshow

How My Pal Pete Got On Antiques Roadshow PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P…

PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Very imformative and professional point of view. Thanks