Saint Thomas Church, Strasbourg, before 1842. Public domain image

Wes Cowan talks about collecting 19th Century photographs, including daguerreotypes, CDVs and stereoviews. Cowan, who appears as an appraiser on Antiques Roadshow and is a regular cast member on the PBS show History Detectives, is founder and owner of Cowan’s Auctions, Inc. in Cincinnati.

I’ve always been interested in antiques. As a kid, I collected a variety of stuff – fossils, rocks, minerals, natural history stuff, Indian artifacts and antiques. I grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and my mother had a lot of Victorian antiques. We lived in an old Victorian neighborhood, one of Louisville’s old traditional neighborhoods. In the 1910s and ’20s it had been very vibrant, but started to go downhill after World War II when people moved to the suburbs. It was a natural place for antique dealers because the rent was cheap, so there was a high concentration of them.

By the time I got into high school, my interest in antiques was waning. I became interested in archaeology. When I was in graduate school at the University of Michigan writing my doctoral dissertation, I started going back to antique shops, probably as an excuse not to write my dissertation. I didn’t really have any money, but I became fascinated with early photography and I could buy photographs reasonably because the antique dealers in the early 1970s didn’t really know what the stuff was.

I could always walk into an antique shop, spend literally a few dollars, and buy 19th- and early 20th-century photographs. I was drawn to them because of the visual impact, but also because they told a story about a person or some historical event that might not have been a big historical event but was certainly peripheral to some event in American history.

It wasn’t long before I met other people in the southeast who were photograph collectors and found that these people would actually pay me for the photographs I was buying from antique dealers, or trade. By the time my dissertation was completed, I was well on my way to being a collector and part-time dealer of 19th-century photography.

My collecting interest gradually evolved into stereoviews (also known as stereographs). I was very interested in 3D card photographs and collected those very heavily for a number of years, but I don’t really collect them anymore. I still have a pretty fine collection of them, small but very nice.

I became disillusioned with collecting photography, because, as most collecting categories do, it went through a cycle. First is the rediscovery by some group of people. Then there’s a run-up in prices, a Gold Rush mentality, and then the market matures. I became very disenchanted with the idea that what started off for me as a pleasing hobby evolved into money, money, money. There was too much competition, and I just felt like I didn’t want to participate in it.

But also, as I became exposed to different kinds of antiques, I found lots of other kinds of things that I really liked. When you collect stereoview cards, they sit in a drawer and you can take them out and look at them, but it’s not like having a nice piece of furniture or a painting or a piece of folk art that you can walk by and touch and have it be a part of your life. So that’s what I’m collecting now. I’m very interested in Midwestern decorative arts and folk art and paintings, things that were done primarily before 1840.

Collectors Weekly: How did you know which photographs to buy, when you first started collecting?

Cowan: I didn’t. It was whatever I thought was interesting and appealing. Like all collectors, I went through a period of just buying all kinds of stuff. Then as your interest and knowledge matures, you look back at your early purchases and say, what was I thinking? My interest in what I was buying evolved as I became better educated.

There’s a huge world of 19th century photographs, and I’d never presume to dictate to a collector what their individual taxonomy should be. I’ve always taken a historical taxonomy to what photographs were available during what particular period of time. Then the social context and historical context of that particular process, and then what the photographs represent within those particular periods.

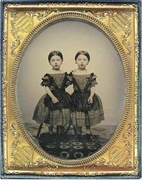

If you’re interested in the earliest history of American photography, for example, then you’re going to collect daguerreotypes [see image at top], because that’s the first commercially viable photograph that was produced in the United States. The daguerreotype is a copper plate that is covered with a thin layer of polished silver. The image, which generally comes in a little leather case, looks like a mirror when you hold it one way, and if you tilt it another way, you can see the image itself. A lot of people at the time called the daguerreotype the mirror with a memory.

Daguerreotypes were introduced in the United States in 1839 and were the dominant form of photograph taken until the mid-1850s. Their success exploded in the early 1840s. People tend to think that the daguerreotype is a fairly rare type of photograph, but it’s not. The initial daguerreotypes were very expensive and not very many were taken because not many people knew how to do it. But by the mid 1840s prices had been dropped to the point where the average person could have their picture taken, and there were literally hundreds of thousands of daguerreotypes, if not millions, taken in America. And they’re still around.

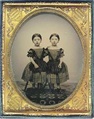

The most common daguerreotype is a studio portrait – somebody went to a photographer’s studio and had their picture taken. So if you collect daguerreotype portraits, you have a lot of options. Do you want to collect daguerreotypes of children with their toys or pets? Daguerreotypes of whole families? Daguerreotypes of female sitters, male sitters, men wearing hats, men smoking cigars? There’s a huge range of avenues to pursue. But if you want to collect daguerreotypes that were taken outdoors and show scenes of buildings or streets, they’re far fewer by a factor of probably a hundred or more.

In the mid-1850s, the daguerreotype was replaced by another photographic process called the ambrotype process. The ambrotype process is basically a photograph on glass to negative made positive by putting a black backing on it. Then the tintype started to become popular in the late 1850s. The Civil War gave a kick in the pants to American photography in a huge way, because every Civil War soldier wanted to have his picture taken. I would guess the average Civil War soldier had his picture taken three or four times during the course of his service.

“Many Civil War photographs credited to Mathew Brady were taken by people who worked for him.”

Paper photography was being experimented with on both sides of the Atlantic, but the French were initially more successful than American photographers were with it. By 1859, a new style of photograph had been developed in France was introduced in the United States. That was the carte de visite, or the CDV as you’d say. It was based upon a calling card that had been in common usage in the mid-19th century – something you’d drop in somebody’s bowl when you came to visit them that had your name and how to contact you. The photographic carte de visite has its roots in that calling card.

Paper photography was introduced to the United States in a big way in the late 1850s, just in time for the Civil War. Photographers were very clever in that they found a way to develop a camera that would take multiple exposures at one time. A Civil War soldier might go into a photographic studio in 1860 and have a dozen photographs made for a couple dollars. These dozen photographs might be taken with a camera that had six or eight lenses, so they’re taking an identical six or eight photographs at the same time. There were literally millions of carte de visite photographs taken between 1860 and probably 1875, including hundreds of thousands taken of Civil War soldiers.

Collectors Weekly: Is the survival rate of paper photographs better than the other types?

Cowan: I don’t know, but there were more paper photographs taken because it was a cheap way to make a picture. Condition can be a big issue if the photographer was sloppy. Many photographs that were taken in the 1860s are still around and look just like they looked in the 1860s. But if the photographer didn’t take care to wash or to fix his prints, then they deteriorate. In general, it’s not the process, how they were taken care of by the photographer. People think a sepia toned photograph is an old photograph, but sepia toning is a product of a photographer not using good chemicals and not fixing the prints to keep them from fading.

New troves of 19th Century photographs are being discovered every day; important discoveries. There are plenty of photographs still out there. I’m not sure that the supply will ever be depleted. There are important things still to be found.

Collectors Weekly: How significant are big-name photographers to 19th-century photograph collectors?

Cowan: Big names are often associated with some of the most iconic images of the 19th century. There were many great 19th-century photographers. Mathew Brady was the entrepreneur in the Civil War, but many photographs that are credited to him were taken by people that worked for him. A lot of those guys went on to very important careers. Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, for example, worked for Brady. They didn’t like working for him because he took all the credit and didn’t give them any.

George Barnard was another great Civil War photographer who began his career in western New York and went on to make a name for himself. He was a photographer for the Army, and then after the war published a monumental book about the Civil War, an iconic photographic book. A.J. Russell was another great Civil War-era photographer who was actually employed by the U.S. military railroad to take photographs. He’s a guy people don’t know very much about, but he made unbelievably great photographs.

After the war, lots of these guys went on to have careers in the American West. O’Sullivan moved west and accompanied several government expeditions. Gardner was hired to work for some of the railroad companies that were building the Transcontinental Railroad. They were looking for routes, so they hired Gardner to go out and take pictures of the scenes along the way. Russell went along the northern route of the Transcontinental Railroad and took photographs, primarily stereoviews. He marketed those stereoviews to make a living, but he also took larger format pictures and some important early photographs.

Collectors Weekly: Why were stereoviews so popular?

Cowan: They were a great form of parlor entertainment. There was no television, no radio, and newspapers didn’t have any photographs, so this was a way for people to look at the world. You’d pass a stereoview around, and you were immediately thrust into the scene.

Stereoviews started being made in the late 1850s, but their heyday was in the 1870s, when any medium size town had a photographer taking them. They were sold locally; if there was a stationery store in the town, you could go down there and buy stereoviews that were being marketed by other photographers from other parts of the country.

Starting in the late 1880s, a number of companies decided that they were going to mass market stereoviews and opened offices regionally in various parts of the United States. They had salesmen going out and trying to sell them to homes and schools. They would basically put together a set of stereoviews of China or Greece or Germany or some foreign country and put them in a box.

There were half a dozen companies by the mid-1890s doing this. The Keystone View Company of Meadville, Pennsylvania ultimately bought out all their competitors. Keystone’s motto was “a stereoscope in every home,” and they had regional offices all over the United States that marketed very aggressively to schools and libraries. The sets they sold often came in a box that looked like a book, so you’d open the box and there’d be 50 or 100 stereoviews inside you could look at.

Keystone sold stereoscopic libraries to schools which would have a tour of the world, for example. They came in 100-card, 200-card, 300-card, 600-card and 1,200-card sets that would take you literally on a tour of the world through the stereoscope. By the 1920s, that market started to fade. Newspapers started to have more photographs. There was radio. People were getting news in different ways. The Keystone View Company finally closed its doors in the mid-1960s, and all their negatives now are at the California Museum of Photography in Riverside.

Collectors Weekly: Have you noticed any recent trends in collecting 19th-century photographs?

Important Long-Lost Quarter Plate Daguerreotype of John Brown, the Abolitionist, by the African American Daguerreotype Artist, August Washington

Cowan: eBay has been a great leveler of the marketplace for 19th-century photography as well as American antiques in general. That’s not true at the top of the market, but certainly for the vast majority of collectible 19th-century and early 20th-century photography, eBay has depressed the market, just like it’s depressed the market for R. S. Prussia and Fiesta ware and carnival glass. You name it, if it was produced in a factory, the value of this stuff has gone down.

Some images that are incredibly rare and important have still held value, but if you were a person who was collecting Keystone View Company stereographs in the 1970s and paying $10 or $15 for a Spanish American war stereoview, today that stereoview is worth $3 or $4 because there were so many produced. So it’s been great for collectors.

If you’re a daguerreotype collector, you want to collect large daguerreotypes of unusual subject matter. We sold a daguerreotype of John Brown last year, one of six known to exist, for $96,000. A few years ago, we sold a daguerreotype taken during the vigilance period in San Francisco in 1852 that sold for $129,000. If you’re a daguerreotype collector, those are the ones you’re looking for, not a mundane portrait that’s a snapshot of somebody in the 1850s. Scarcity and condition are the driving factors.

I wish I could tell you I know of a lot of photograph collectors in their 20s and 30s, but I don’t. I think this is a reflection of the antiques business in general, not just photography. Most people that are collecting seriously are in their 40s and up. That’s when you hit your stride in terms of disposable income.

Collectors Weekly: Is the market for 19th century photographs primarily American collectors, or is there a global interest?

Cowan: Primarily. There are European collectors that would collect an iconic 19th-century American image, but primarily it’s an American market, and not necessarily people that are just interested in photography. Somebody may be interested in the history of the American West, and they recognize a great photograph of Dodge City, Kansas in 1870 that will go well with their Kansas collection. There are many people collecting the story behind the image and the history behind the image, too.

Collectors Weekly: What about markings or signatures on photographs – is that a major issue?

Cowan: It can be very frustrating at first if you see a great image, and want to know where it is, but there’s no indication. A lot of 19th-century photographs were mounted on card stock or a board that the photographer imprinted his logo or address on. But there are many, many anonymous images that you find and say, gosh, I wish I knew where that was or who this is or what this scene is.

There are some people who have cataloged photographers’ imprints, and they’re great sources. If you’re a daguerreotype collector and you find a signed daguerreotype, you definitely must go to www.daguerreotype.com, the online database of a guy named John Craig from Connecticut. John has been a photographic dealer for 40 or 50 years. He published two massive volumes on daguerreotypes, and then once the Internet came around, he put them online at his own expense. It’s absolutely free. There’s no advertising on there. He’s received awards from the Daguerreian Society.

Carl Mautz, a book publisher who lives in Nevada, publishes Western photo history books. He published a book called Biographies of Western Photographers, and it’s mainly 19th-century photographers. It’s a wonderful reference; I use it all the time. It’s a 600-page labor of love.

If you’re a stereoview collector, there’s one great book you want to have in your library: The World of Stereographs by William C. Darrah. It’s out of print, but easy to find, and it gives you a great history of stereo photography.

There are great overviews of the history of American photography. One is by Robert Taft, Photography and the American Scene. It was published in the 1940s, but it’s a classic book on the history of American photography and I recommend it for anybody. Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839 to 1889, is also a great book. William Henry Jackson was a great photographer who began his career in the east and ended up in Colorado. He was one of the first photographers to publish photographs of the Yellowstone Country. His photographs were distributed to Congress and directly led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park.

Collectors Weekly: It seems like a lot of these photographs are ripe to put on the Web. Is anybody doing that?

Cowan: I don’t think anybody is yet. It doesn’t mean it won’t be done. We are going to open our photographic archive up beginning in 2009. We probably have 15,000 or 20,000 photographs on our website right now that people can look at from our prior auction catalogs. Arguably, we’ve probably sold more 19th-century photographs than any other auction house in the country, outside of eBay, in the last 13 years.

Collectors Weekly: Any other advice for people thinking about collecting 19th-century photography?

Cowan: The same advice that I give to everybody, and it’s the same for any kind of antiques: collect what you like. Learn everything you can possibly learn. Buy the very best that you can possibly afford and be a collector, not an accumulator. With photography in particular, you can collect a photograph for the historical value of it, and collecting it for historical value, you might not care as much about its artistic merits. If you’re collecting for artistic merits, you need to learn to be a connoisseur, but if you’re collecting for historic merit, who cares?

(All images in this article courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, Inc.)

Daile Kaplan of Swann Auction Galleries on Collecting 20th Century Photographs

Daile Kaplan of Swann Auction Galleries on Collecting 20th Century Photographs

From Ambrotypes to Stereoviews, 150 Years of Photographs

From Ambrotypes to Stereoviews, 150 Years of Photographs Daile Kaplan of Swann Auction Galleries on Collecting 20th Century Photographs

Daile Kaplan of Swann Auction Galleries on Collecting 20th Century Photographs The Woman Behind Bettie Page

The Woman Behind Bettie Page PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P…

PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

ive recently have obtained glass photos early 1900s from a photographer named GEORGE W.SWAIN UofM expidition with a profesor KELSEY.Some early

phtos of buildings,egyption artifacts im wondering what they are worth to a collector of early ann arbor michigan.approx 130 glass photos

My husband gave me for birthday this photo album with 79 pictures.

The name on the cover is:

FRIESTEDT UNDERPINNING CO.

BUILDING, SHORING AND FOUNDATION CONTRACTORS

NEW YORK

These pictures was taken by well-known photographers: Edwin Levick, PEYSER & PATZIG and W. D. Hassel in 1922 in New York (these photos have photographer name on the back)

There is also 2 other photos with stamp on the back: PROPERTY OF THE HAYWARD CO

NEW YORK, N.Y

I would like to know the value of these photos.

thank you.

My brother has a tin type of an ancestor who served in the civil war. Is there a safe way to make a copy of this?

I have some stereoptican photos that I would like to know more about. Is there someone I can contact to go into this at more length? I live in Grand Rapids, MI. Thank you.

I have recently found a set of glass picture slides from 1890- 1930 of early nursing in US. Could you advise where I can find out more about these? Thank You

I have a Daguerreotype or Cartes de Visites of a woman on a STERLING SILVER dinner type plate. Was this common and what are they called ?

I am researching a ancestor of mine, who was professional american 19th Cent. photographer, His name is L.H. Geer (Luren H. Geer) . His wife Rosetta Geer was accomplished painter as well, and had done potraits. I know from 1860 til his death in 1903 he took potraits, and scenery photographs. He traveled great deal and lived in several different states. The earliest I can find he was taking photos in Jackson, MI the year 1860. Here is my question, do you know if these earlier photographers were trained somewhere, or did they just purchase the equipement, and start their business? I know that Geer was born in New York state, lived in Michigan, then went out to Montana Territory, then down to Alambama, and eventually to Orlando, FL around the 1880’s til his death.

TJ Thompson, I found the gravestone of Luren, Rosetta and their daughter. I took a pic of it, you can email me at theresuh187@gmail.com if you ever see this and want to see the stone, it’s really beautiful.

I have a picture of my great grandmother made by Geer in Alabama. Do you know when he was in Alabama? I am attempting to date the picture.

Thanks Eleanor

I just published a book Shot in Alabama: A History of Photographt 1839-1941 and a List of Photographers (U AL Press 2017). In the List, there is an L. H. Geer in Tallasee. Geer was born in 1832 in NY and is listed in the Elmore Co., Tallasee Cenuse for 1880. If you have a scan of the piture, I’d love to see it. Frances Robb

I have some 30 stereographs made by my great grandfather George Barker. Almost all are of Niagara Falls. Also have 3 of his medals. Any suggestions for having them evaluated? Thank you!

Great article! I collect old photo’s for historical interest. My special interest is in police and military themes. Dating the pictures can be a problem. Having a list of photographers and the dates that they were in business would be a great help in narrowing down the actual date of the photograph. For example some police departments use the same badge designs for over a century. A picture of a Police man with a visible badge number taken by a known photographer and his known dates of operation can help narrow down the date range of issue for the badge numbers. Are there photographer lists by state available?