A Comparative Study of Design and Craftsmanship

This article discusses the history of glass paperweights, from their original designs and production processes to their spread across the world, noting some of the major manufacturers and design styles. It originally appeared as a two-part series in the February and March 1942 issues of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antiques collectors and dealers.

Part I:

(Editor’s Note: Although glass paperweights have been collected in the United States for over a generation, and for longer than that in England and Continental Europe, certain obvious facts have not been included in what has been written on the subject. Most of these have been learned by studying and handling a great number of examples from the wide range of factories at which they were made.

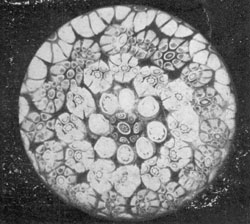

A Clichy Design in Millefiori: For its mark this factory used rose canes, a central one with a capital C and, infrequently, the entire name Clichy in such paperweights.

It is with no idea of contradicting the carefully written articles and books that have already appeared that this restatement of the subject is written. Information for it has been gathered from various individuals who have given paperweights careful consideration for a long time. Some of it has been told to the editor with no thought that the comment would be quoted or the person’s name cited. Therefore, this review must not be considered as original research by the writer but rather a summary of facts and opinions gathered by numerous conversations with paperweight specialists over several years.)

A Venetian Example: In this crown type the decorative design was obtained by use of two kinds of spiral thread glass rods alternating with ribbon-stripe bands, as well as regularly placed air bubbles.

The first paperweights were undoubtedly bun-shaped pieces of plain glass. Just when those with an embedded pattern in color appeared, we do not know, but they probably originated with the glassworkers of Venice. The technique involved in their making harked back to the Roman Empire and, along with other glassworking methods, reached modern Europe in a roundabout way about the 13th Century.

In Roman times, rods of various colors of glass were welded together into highly decorated patterns, the beauty of which was seen when cut to show a cross section. Roman craftsmen cut these mosaic rods in pieces about a quarter of an inch thick and by reheating formed them into small bowls and decorative objects.

A Baccarat Fuchsia: Here the design of blooms, buds, leaves, and supporting stem rests on latticinio interlacing white threads of circular pattern.

When this technique reached the Italian glassworkers, they were quick to use these mosaic cross sections in various ways and they also gave them a name. It was millefiori or thousand flowers. In time, circular or geometric arrangements of such cross sections became the most widely used means of providing decorative designs that could be embedded in the glass casing of paperweights.

Another Venetian glass technique that was later to find wide use in paperweight making was the interlacing threads of opaque white glass, circular in form and often somewhat basket-like in shape, that formed the background beneath the more important central decoration of many paperweights.

Millefiori from Saint Louis: The canes are characteristic of those of this French factory. Those with the identifying initials were placed inconspicuously away from the center. Coloring was in pastel shades.

The name of this, latticinio, is also Italian. The Venetians developed the twisted filigree and the intricate chaplet bead as well. Both were first made in rod form, much as was the millefiori. Drawn out wire-like to the desired diameter, both were then cut in short pieces and, by reheating, bent into the shape wanted for use in the paperweight design.

Since well over half of all the collectible paperweights have in their decorative ornamentation one or more methods of achieving a design that was used, if not originated, by the Venetian glassworkers, it is obvious that, directly or indirectly, the art of the paperweight maker in whatever country he may have worked was the further development of their technique. In fact, when last known, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London had two millefiori paperweights in its glass collection attributed to 17th-Century Venetian provenance.

French Type, Sandwich Made: The design, standing flowers, leaves and stems and concaved latticinio background are typically Gallic, although the quality of workmanship and glass show clearly it was made at this American factory.

But from the relatively few that have survived, it is generally held that the glass blowers of that city on the Adriatic were not prolific makers of paperweights. But those few can be readily recognized. First, the colors that form the design lack brilliance; second, the design is not too well executed; and, lastly, the clear casing being made of lime glass has neither the sparkle nor weight of examples made elsewhere with lead glass.

But, as is well known, the art of glass-working was not long confined to Italy. Some Venetian craftsmen escaped and those from other Italian cities were allowed to go abroad to practice their craft on a basis of payments that compensated for their migration. They went to France, Bohemia, the Low Countries, England, and Germany. Under royal or noble patronage, these Italians established glasshouses. And in time their descendants, or native workmen trained by them, made paperweights of far finer quality than those originally produced back in Venice.

Profile Portrait of Cornwallis: Aspley Pellatt of London obtained a patent in 1819 for such profile medallions embedded in glass with the appearance of silver.

In France, for instance, there were the glass factories of Saint Louis, Baccarat, Clichy, and others. Here, paperweights of remarkable artistry were produced in large numbers. Although 1820 has been put forward as the time when the first ones were made at the Saint Louis factory, which were of crude work, there now seems to be indications that paperweights of fine design and superior workmanship were produced two or three decades earlier than the signed and dated ones of the years from 1845 to 1849.

Also, these three factories unquestionably made paperweights for some years after the dates given, and in addition to the millefiori type produced many with other design motifs. Flowers, fruits, vegetables, insects, and reptiles were blown in naturalistic colors. There were also the weights, popularly known as candy type, because short lengths of millefiori sticks seem placed hit or miss like hard candies in a partly filled jar. Sometimes these seem to be resting on a background of hair-fine threads of white glass; sometimes on a lacy pattern; and sometimes on a background as formless as a fleeting cloud.

Baccarat, Marked B, 1848: In this the millefiori canes, some of animals, birds, or butterflies rest on duplicate white lacelike background.

In many but not all instances, the paperweights of these three factories bore somewhere in their design a name or initial. The marked ones at Saint Louis have the initials SL incorporated in small capital letters at an inconspicuous place in the ornamental design. These were in dark color surrounded by a cross section of cane made of white glass. Also, the tones of colored glass approach pastel shades not found in the paperweights made at either Baccarat or Clichy.

Fruit Group from Cambridge: Both central design and latticinio background were of Baccarat origin, although the work was done at the New England Glass Company factory.

At Bacarrat, where millefiori paperweights of exquisite design and fine craftsmanship were made, one of the cross sections is apt to be slightly to one side of the center in the design and the canes seem to rest on a lacelike background. With or without the initial B, some of the canes bear the silhouette of four-footed animals, birds, or butterflies.

This same factory also produced weights where the design was a flower with bud, leafage and stem arranged most naturally. Occasionally, one finds the stamens of the flowers replaced with a bit of cane bearing the capital B. Here also were made weights with a fruit or vegetable design. With the former, leaves and stem form the background; with the latter, interlacing threads of white glass called latticinio were used.

Sandwich Copied Clichy: The millefiori canes, some with rose centers, and their arrangement bespeaks design of the Clichy factory but the glass, especially casing, is distinctly Sandwich origin.

A distinguishing mark with the Clichy paperweights may be a white, pink, or a yellow rose or, less frequently, a purple one. With those of millefiori design, one or more of the canes may bear the rose or a cane showing a capital C in dark color, red, or green as its central design. A few paperweights bear the name Clichy, but they are less frequently seen than those with the rose or C mark.

As so many paperweights have been discovered with identifying initials, name, or distinctive flower in European and in various sections of North and South America, it is logical to wonder if these factories did not include paperweight making as part of their regular commercial production. If not, a large proportion of their best glass blowers must have spent a considerable amount of their free time preparing intricate designs for encasing in clear or overlay glass.

Before World War II began, this question of commercial paperweight making was put to an official long associated with the Baccarat factory. After careful search of the company’s records, his reply was that while this was possible, he could find no price lists, correspondence, or other data to substantiate or disprove the theory that paperweights were made there as standard commercial products.

Yet the sizable proportion of weights made at all three French factories with identifying devices, frequently accompanied by a date year, would seem to be good evidence that these pieces formed a regular part of the glasswares made. Again, the designs used in the millefiori weights were so intricate and finely wrought, often involving expensive dies, as to make it seem unlikely that glass blowers could produce them after hours and at their own personal expense. Similarly, the flower, fruit, and kindred designs were so nearly standard in shaping and colors of glass used as to make them somewhat as interchangeable as are automobile parts today. This would suggest factory production with especially skilled workmen assigned to such work.

Part II:

Three Millefiori Glass Doorknobs: That at the left has been faceted on a cutting wheel to make it more nearly square. The one in the center and that at the right are typical of the millefiori paperweights made at American factories — probably Sandwich. All have shanks at the base so that they could be mounted in brass for use as decorative hardware.

The price of paperweights made at Saint Louis, Baccarat, and Clichy in many cases was comparatively little. One wonders wherein lay the profit, even in the 19th Century with its standard ten to twelve hours working day and the relatively modest rate of pay received by even the skilled craftsman. Of course, a high degree of skill and infinite patience in hand-finishing work, whatever his craft might be, have long been the twin talents of French artisans. Those producing the paperweights would also need distinct artistic gifts for color, form, and arrangement.

Millville Water Lily: In this paperweight the flower is complete with stamens. This is the most unusual of the lily paperweights made by Barber.

Suppose each such glass blower was also a rapid workman, completing a paperweight every hour on the hour, what a small percentage of the original price of one of these paperweights that are now expensive antique collectibles could have been his if the factory were operating at a profit. For the ultimate consumer might be living half around the world from France. And in addition to the cost of production at the factory itself, there would be a retailer’s discount, salesman’s or resident agent’s commission, and shipping charges.

A Baccarat Butterfly: This design, of butterfly in the center with millefiori canes inset in the wings and with a background of other canes almost horizontal, was a specialty of the Baccarat factory.

Taking the skill of workmanship and the time required for paperweight making into consideration, it would indicate commercial production could not have yielded commensurate profit for a factory. In the light of these facts it seems indicated that these decorative glass spheres were largely the personal work of certain glass craftsmen done after hours on their own time. This clearly explains why the design of paperweights are so individual, especially those made by workers in the American glass factories.

Further, it is known some of the factories, for instance, Whitall, Tatum & Co. at Millville, New Jersey, found that casing and annealing of the paperweights made by their glass blowers seriously interfered with regular operations. As a result the management restricted such casing and annealing if it was not forbidden.

A Gillerland Millefiori Pattern: Many paperweights were produced at the Gillerland factory in Brooklyn. They were mostly of the millefiori type.

There is a possibility that these French glass factories knew that they were losing money on every paperweight and were content to have it occur, since the beauty and demonstration of the art of working in glass which these artistic objects portrayed reflected advantageously on the other types of glass they were making. So these paperweights became a valuable and effective means of advertising.

But failure to make a profit, however small, on any object does not seem characteristic of the Gallic temperament. So paperweight making, if it was a factory enterprise at Saint Louis, Baccarat, or Clichy, must have yielded a return or it would not have continued. The height of it, according to weights bearing factory initials and a date, was apparently from 1845 to 1850, but it is reasonable to suppose that production did not cease until the disasters of the Franco-Prussian War and the business difficulties that followed in the train of this invasion of France by the German armies.

Millville Commercial Product: This paperweight, used for advertising by S. P. Shotter el Co., Savannah, Georgia, dealers in oils and turpentine, is of the picture type made at Millville. In the upper right-hand corner can be seen a typical scene at a Georgia turpentine distillery.

There is another way in which paperweight making by these French factories may have brought in a cash return. This was by selling the millefiori, twist, beaded rods, and blown pieces that formed the flowers and fruits to individual glass blowers working in factories in other countries who wanted to augment their regular wages by paperweight making after the regular day’s work was completed.

Again there is no direct evidence to prove that these three French factories, or others located in other European countries, carried on a trade of paperweight parts. However, with some of the earlier paperweights made in the United States, anyone conversant with those of both Europe and America can at times spot examples where elements of the “set-ups” have color and form characteristics peculiar to a factory on the other side of the Atlantic, although the casing glass is equally distinctive of one of the better-known American glass factories. A flower group of three five-petaled flowers with stems and leafage characteristically French in color, form, and arrangement, but encased in glass that is obviously of Sandwich origin, is a good example to cite.

Sandwich Fuchsia Paperweight: Here the center of the flower is formed by a cane which has the typical Clichy rosebud design in the center.

If the quality of casing glass is early Sandwich, then a reasonable deduction is that the glass of the floral group was French made and shipped to the factory on Cape Cod. If, on the other hand, the casing glass is obviously of a later period, the probabilities are that the entire piece was Sandwich made and dates after the time when Nicholas Lutz or some other French trained craftsman had migrated to this country and was working at Sandwich.

Although the five-year span preceding the middle of the 19th Century has been taken as the height of paperweight popularity, there are records to prove that they were much in fashion at least thirty years earlier. For example, Apsley Pellatt, owner of the Falcon Works of London, found them so much in favor that in 1819 he obtained an English patent for making portrait medallions for use in paperweights.

Millville Paperweight Mounted On Goblet-like Base: Here the central figure is a sulphide crucifix and the background is of mottled green and brown glass. This was originally made as a flat paperweight and the footed base was developed later.

That profile portrait paperweights were in fashion some years before the Battle of Waterloo is evidenced by one made at Baccarat, which portrays Napoleon Bonaparte as a comparatively young man wearing a victor’s laurel wreath. It was designed and signed by the artist, Andrieu. An example of this paperweight is now in the collection of Mrs. John H. Bergstrom of Neenah, Wisconsin, and was illustrated in her book, Old Glass Paperweights.

There are others of the profile of Queen Victoria as a young woman; of Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenia in overlapping profiles; and of various people prominent from the Napoleonic era until several years after the end of our own Civil War. Then the Pairpont Company, New Bedford, Massachusetts, produced a paperweight with a profile of General Robert E. Lee.

Cambridge, with Foreign Millefiori Sticks: In this paperweight, the latticinio background was used. The rabbit, seen in the seven canes with dark background, was not as carefully executed as most of the animal silhouettes made in Europe.

Paperweights were not made in American glass factories until some years after they became popular in Europe. Even then their quality was inferior until some highly skilled glassworkers from some of the leading European factories migrated to this country and began to make weights here.

Among these were Nicholas Lutz, who was trained at Saint Louis and later worked at Sandwich; Francois Pierre, who started at Baccarat and later made paperweights at the Cambridge factory of the New England Glass Company at about the same time as John Hopkins arrived, it is believed, from England; John A. Gillerland of Brooklyn, New York, was first renowned for the superior cut and engraved glass made in his factory. Later he won prizes for his fine millefiori faceted paperweights. Also, among others, there was Christian Doerflinger, born in Alsace-Lorraine, who opened his own factory in Brooklyn in 1852 and later moved it to White Mills, Pennsylvania.

Although American glass craftsmen started by making what they had learned in some European factory or by copying paperweights of European origin, American individuality, in time, made itself manifest. Outstanding are the blown paperweights in the shape of apples or pears of naturalistic coloring that were fused on round crystal bases. These were the work of Francois Pierre, from Baccarat, who made these at Cambridge. They were totally different from any ever made at any foreign factory.

A Cambridge Sulphide Paperweights: On the back is the inscription: "Kossuth, Governor of Hungary, set at liberty by the people of the United States of America, 1851." This paperweight is in the manner patented by Aspley Pellatt of England in 1819.

Although no direct evidence to substantiate it has been found, doorknobs that were essentially millefiori paperweights seem to have been made in Europe, at Sandwich, and possibly at Cambridge, and some other American factories in quantity. These found a ready market in South America. As they were in the nature of commercial production, the quality of workmanship of these doorknobs is not equal to paperweights of the same kind. Also, the design and arrangement of cane set-ups in such knobs were simpler than millefiori paperweights of the same origin. This explains why knobs cannot be found that are as fine as similar paperweights.

A Cambridge Pear: This paperweight is characteristic of those made at the New England factory by Francois Pierre, who originally worked at the Baccarat factory.

Other unique paperweights, of course, were those made by Ralph Barber of Millville, New Jersey, in which a rose just coming into full bloom with delicate leaves, stem, and sometimes an unopened bud, were made in most lifelike manner. He made his roses with opalescent tips to the petals and formed his blooms of glass that varied from a rich red to a delicate pink. He also made some of canary yellow, green, or other shades that resulted sometimes accidentally because of high temperature used in making.

Fragment of an American Paperweight: At the left, this fragment is photographed from the underside to show how small the decorative design of colored glass was. At the right, it is seen as magnified by the spherical curve of the glass casing.

Besides his roses, other motifs were calla lilies, water lilies, or tulips. In each, the flower was represented as in full bloom. These were accomplishments in paperweight making totally different from those of any other glass craftsmen. Yet his regular work was making special pieces of glass for druggists and laboratories and the years when he made his distinctive paperweights were from 1905 to 1912. For part of the work, special tools were needed. He made these as well. He lived until 1936 and so had the unique experience of seeing collectors eager to pay premium prices for his flower paperweights, which defy reproduction that he had originally sold for one dollar and fifty cents each.

Regarding reproductions of any of the fine old paperweights, these copies will, on examination, be found incorrect in colors, skill of workmanship, or the quality of the casing. Proper colors, craftsmanship of the first order, and characteristic casing are the points on which an opinion is formed as to whether or not a weight is an original or a copy.

Filigree Glass Knife Rest Paperweight: Polished in eight-sided form, this shows the thread filigree work originating at Venice. The most prominent is the white, spiral ribbon thread. Inside this is a chaplet-bead threading of ruby glass and through the center is a single gold thread.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of If These Shirts Could Talk: The Tantalizing Tales Behind Used Clothes

If These Shirts Could Talk: The Tantalizing Tales Behind Used Clothes The Force of Collecting Star Wars Cards

The Force of Collecting Star Wars Cards Dawn of the Flick: The Doctors, Physicists, and Mathematicians Who Made the Movies

Dawn of the Flick: The Doctors, Physicists, and Mathematicians Who Made the Movies World's Foremost Bedpan Collector Celebrates Objects Most People Pooh-Pooh

World's Foremost Bedpan Collector Celebrates Objects Most People Pooh-Pooh Art Glass PaperweightsSome of the earliest paperweights were made in Venice in the 1840s. They we…

Art Glass PaperweightsSome of the earliest paperweights were made in Venice in the 1840s. They we… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

As a new collector of paperweights I found the article very informative and helpful. I have a millefiore paperweight that was made at Pershire in Crieff Scotland and a candy type with shank that I know little about. Any suggestions for literature and information would be appreciated.

Hi, I found your paperweight article very interesting, however, I have been trying to research a set of etched art deco glass dishes, decorated with suits of cards. They have a small butterfly etched in them also, I have seen this before, and always assumed it was Baccarat. However, I cannot find this mark in any of my books or on the internet and am beginning to think I imagined this information. I would be very grateful if you could shed a little light on my problem. Thank you. Helen

i have a paperweight containing the seed head of a dandilion but cannot work out the makers name any ideas ?????

Very interesting article!

Just one correction, though. You state in the caption of the photo of a Cambridge Pear that Francois Pierre had originally worked at the Baccarat factory. Francois Pierre was my great-great-grandfather and I’ve done quite a bit of genealogy research on that line. Francois was born in Saint Louis les Bitche and on his birth record it indicates that his father was employed as a glass worker. I have found no indications that anyone in his family worked at Baccarat. My assumption (and it is only that) is that he and his father were both employed at the Saint Louis factory.

I have a very interesting paperweight it’s in the shape of a mushroom and is about four inches tall, if you could please e-mail me I could send pictures trying to find out who made it and when. Thank you for your time.