It’s 1520 in Augsburg, Germany, a bustling cosmopolitan city at the height of the Northern Renaissance. On his 23rd birthday, Matthäus Schwarz, a successful accountant with a flair for dressing well, launches a special project he calls his kleidungsbüchlein or “little book of clothes.” Schwarz had been fascinated by historic clothing trends since he was a child, and like many at the time, he was inspired to experiment with new media, blurring the boundaries of art, fashion, and self-representation.

“In my mind, I was a bad ass.”

With nary a smartphone in sight, Schwarz did what any great Renaissance fashionista would: He found a local artist, Narziss Renner, to help him render a series of exquisite selfies documenting his personal wardrobe in precise detail. Renner began by illustrating scenes from Schwarz’s childhood, moving from his birth up to the present, after which they continued adding sketches of Schwarz’s new outfits to the series chronologically. With Renner’s assistance, Schwarz recorded the clothes he wore for special occasions, like wedding parties or dances, as well as more mundane affairs, like his commute to the office. Each of the elaborate illustrations was accompanied by a caption written in Schwarz’s own hand.

Though forced to work with different artists following Renner’s death in 1536, Schwarz continued the project until 1560, when he was 63. Eventually, the 75 sheets of parchment featuring 137 different portraits would be bound into a small manuscript, measuring just 10cm by 16cm (or 3.9″ by 6.3″), creating a unique, trailblazing fashion diary. Schwarz also encouraged his son, Veit Konrad, to begin a similar project, but Veit lacked his father’s passion for clothing and stopped adding to his manuscript while still a teenager.

Top: A portrait of Matthäus Schwarz at 26 years of age. © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-60). Above: The caption for this page (showing Schwarz at age 2) reads, “On 22 November, 1499: I suffered cramps for nine hours, so that everyone thought I was dead: I was sewn in and carried to Sant Ulrich. Do the same as me: I moved one foot!” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-2).

Miraculously, both of these manuscripts survived to the present, and thanks to the publication of Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward’s 2015 book, The First Book of Fashion: The Book of Clothes of Matthäus & Veit Konrad Schwarz of Augsburg, they’re more accessible than ever before. Rublack and Hayward’s book offers a detailed look at these documents, including the full manuscripts along with translations of the text, annotated commentary for each illustration, and essays on the project’s historical context. (Though Schwarz referred to his project as a “little book,” it’s considered a manuscript because each page was made individually rather than printed in multiples. The three known copies of the original manuscript, including one viewable on Wikimedia, were also made by hand.)

Browsing Schwarz’s book of clothes is like encountering a 500-year-old street-style blog: His poses are carefully chosen to show off head-to-toe looks in a wide variety of settings, and the handwritten text describes his garments as well as details about what he was doing or feeling while wearing them. “He had this ability to place himself in time,” Rublack says of Schwarz when we recently spoke over the phone, “the sense that while it was probably going to look silly to people in the future, there was something happening here worth documenting because it captured this particular period.” Taken together, the images and their captions give an immediacy to the past, bridging the cultural and temporal distance to make elements of Schwarz’s day-to-day life oddly familiar.

Perhaps the most successful element of Schwarz’s remarkable fashion diary is the fact that he remained committed to it from his youth until late in life. “Matthäus Schwarz realized that fashion tells us something about historical change and that change can be something interesting in the realm of culture,” Rublack continues. “Nobody, of course, had done something like this, and I think Schwarz didn’t realize he was actually chronicling so many aspects of his life through fashion. That entailed difficult experiences, like depicting himself when he had suffered a stroke and was at home, wearing a mourning gown—the kind of things you don’t like to visualize about your life. He had to own up to that.”

The top caption for this image reads, “On October 2, 1516, this was my first outfit back in German style in Augsburg, when I wanted to become a huntsman,” and the text below says, “19 years, 7 months, 10 days.” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-27).

As Schwarz explains in the opening pages of his manuscript, he was inspired to begin this sartorial project on his 23rd birthday. “All my days I enjoyed being with old people, and it was a great pleasure for me to hear their replies to my questions,” he writes. “And among other subjects, we would also get to talk about clothing and styles of dress, as they change daily. And sometimes they showed me their drawings of costumes they had worn 30, 40, and 50 years ago, which greatly surprised me and seemed a strange thing to me in our time. This led me to draw mine as well, to see what would come out of it in 5, 10, or more years.”

Schwarz had been keeping records of his clothing since his teenage years, and he makes several references to another autobiographical work, called The Course of the World (Der Welt Lauf), intended to supplement the manuscript’s brief text. Yet Schwarz apparently destroyed the only copy of The Course of the World sometime before he was married in 1538. “The Course of the World was more personal information,” Rublack explains, “for instance, about his flirtations and dating life. It’s possible he always thought he might destroy that, but I don’t think it was a very extensive diary. One has to remember that his book of clothes was only bound in 1560, so before that, these illustrations were on parchment sheets that he could use selectively, meaning he could have decided whom to show what. It was more flexible than a book, which must be seen as a whole—Schwarz could make decisions about whom to let into what part of his life. But we don’t know anything about whom he actually showed it to or not.

The caption for this image hints at courtship, reading, “On 2nd June, 1527, in this manner: the doublet from silk satin, a riding gown from camlet, the bonnet edged with velvet, all of this to please a beautiful person, along with a Spanish gown.” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-88).

“When he teamed up with Narziss Renner, this slightly younger illuminist painter,” Rublack says, “Renner worked backward to capture Schwarz’s childhood.” However, Schwarz never explains the exact process for sketching his outfits with Renner. “In that first phase, up to his marriage, the book has a lot of images of Schwarz throughout the year, and we don’t know anything about that interaction,” Rublack explains. “All we can say is that it was a very unusual relationship between him and Renner, the illuminist.”

Around the same time, Schwarz also commissioned Renner to execute other projects, including a prayer book, two medals featuring portraits of himself, an illustration of Christ’s genealogy, and a painting depicting several generations of Augsburg patricians at an imagined outdoor dance, a work that inspired a new local genre of painting. Schwarz and Renner were at the forefront of the German Renaissance movement, looking at popular period art forms, such as portrait medals and engravings, as well as cutting-edge visual styles like new techniques for capturing realistic perspective. “They were young men who loved art,” Rublack explains, “consuming the woodcuts and engravings that were coming out at the time. You have to remember that people like Albrecht Dürer were contemporary artists, and it was a very exciting time for the visual arts in the German Renaissance with lots of new experiments.”

When the duo began working on their fashion project, Schwarz had just been hired as head accountant for the powerful Fugger merchant firm, raising his status in his hometown of Augsburg. In addition to being a financial, commercial, and political hub, the booming city was home to several successful craft guilds, including book printing, metalwork, painting, and, most importantly for Schwarz, textiles. (Augsburg’s guilds were later crushed by the emperor during the upheaval of the Protestant Reformation in 1547.)

With Schwarz’s role for the Fuggers came privileged access to businesses and craftspeople working in fashion, as well as the expendable income to afford the period’s extravagant couture or custom-made clothing. But his passion for unique clothing required considerable investment beyond a willingness to incur a steep financial cost. “Augsburg was very much a textile center, and Schwarz could obviously find the right people to work for him,” Rublack says. “The manuscript tells us about Schwarz’s whole investment in the process: Sourcing fabric; having it dyed the colors he wanted; taking it to tailors, seamstresses, and so on. The whole design process was very bespoke. For someone who cared about that, the patron actually became the designer, but it required a lot of time. It also meant that among cultivated people, your clothes could make an impression even if you didn’t use a lot of very expensive materials.” For example, Schwarz’s connections gave him access to half-silk fabrics, which were affordable but could also be used to create interesting visual effects.

A few pages include multiple portraits of Schwarz to compare certain styles, such as this image from June of 1524, where he’s shown wearing three different shirts and three types of Prussian leather hose. According to the text, an eight minute hour-glass was attached to his thigh in the middle outfit. © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-68-70).

Despite the Renaissance atmosphere of change, Augsburg was still governed by so-called sumptuary laws. “In 1530, these laws were mandated for the Holy Roman Empire, so people would have had a sense of what you could or could not wear,” Rublack says. “For instance, Schwarz was pretty careful about how he was depicted wearing jewelry. Wearing gold chains was a sign that you were a knight or a noble, so he never does that. But within those regulations, there was quite a range for what you could do. We have no evidence that anyone in Augsburg during his lifetime was ever fined under these laws; it wasn’t something that seems to have been policed.”

“It was about this new style of delicate, art-loving, subtle manhood that was expressed through an interest in aesthetics, and part of that was fashion.”

That said, Schwarz’s position in the community was also relatively unique. Rublack points out that there wasn’t a clear perception of what the head accountant for the area’s most powerful merchant firm, the Fuggers, was allowed to wear. “The pope and the emperor’s brother both got huge amount of credit from the Fugger family, and they absolutely depended on the money,” she explains. “And of course, it’s easy to imagine that as their head accountant, Schwarz was party to these negotiations about how much credit they would get and what the conditions would be. He had access to the highest politicians at the time.”

Though we don’t know exactly how much money Schwarz made, he was definitely well off, and after he was ennobled in 1541, he’d have even fewer wardrobe constraints. “Schwarz always respected the notion of what was appropriate dress for different situations in his life, but he wore that in a way that suited him,” Rublack says. “One thinks of his mourning dress after Jakob Fugger died—he would’ve really mourned this man who gave him all these opportunities in life, but I don’t think he did that out of obligation.” As was custom at the time, Schwarz’s mourning dress progressed through several stages, beginning with an entirely black outfit covering the body and most of the face, which gradually became less restrictive over time.

Today, Schwarz’s outfits might seem impractical and outlandish—from the close-fitting, padded jackets known as doublets to his tight pants or hose—but he was certainly on trend for the time. “I don’t think he was an eccentric, since his wardrobe was closely oriented in terms of cuts and styles with what aristocratic or upper-middle-class people wore,” Rublack says. “But within that framework, he was also innovative: I think Schwarz would have been known as someone who communicated his passion for fashion. For instance, when he ordered a new gown, he could be very inventive in terms of how the gown was cut—one sleeve might be different from the other, and he is often shown with his arms stretched out so that you can appreciate the experimentation that’s gone into a design.

In February of 1521, when he was 24, Schwarz wore this asymmetrical look to a friend’s wedding reception. © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-47).

“That was also very clear when he went to weddings, a real event to dress up for,” she continues. “You’d wear new, brightly dyed clothes to make a real impression, and he was often with a group of men who went together and chose an outfit to wear as a group. In that sense, it tells us that these styles were shared as well.” Schwarz was clearly enamored with the popular Germain tailoring techniques of “slashing and pinking,” used to give a garment additional texture by adorning it with patterns of long slashes or small cuts, often lined with contrasting fabric. “Schwarz was also interested in bringing in some traditional details, like old Franconian embroidery,” Rublack adds. “For me, that’s the Renaissance spirit—it’s not just about ingenuity and innovation, but a respect for the past.”

Despite wearing garments that appear almost comical today in their complexity, Schwarz’s lived experiences, as explained through his handwritten captions, are surprisingly relatable. His descriptions include everything from comments about his weight to the youthful hubris of his teenage years, of which he writes, “In my mind, I was a bad ass.” One entry from 1521—showing Schwarz in a wide-brimmed bonnet over a red wool coif—includes a later addition that says simply, “I had a terrible headache.” Other pages include more consequential notes, such as the caption referencing a major outbreak of the plague, which reads, “On the 20th August, 1535, when people in Augsburg began to die.”

“That’s the Renaissance spirit—it’s not just about ingenuity and innovation, but a respect for the past.”

However, all of these insights are secondary to Schwarz’s focus on fashion. “Past historians who wrote about this manuscript often thought of it as a book about his life,” Rublack says, “but Schwarz’s key concern is the clothes. Sometimes he tells us a little bit more, like for his childhood, there’s more narrative, but the key phase primarily documents his clothes and innovation in dress.” The pioneering nature of the project also resulted in many unconventional approaches. “They were engaging in experiments themselves,” Rublack says of Schwarz’s collaboration with Renner, “some of which were very intimate, like the two pages where Schwarz shows himself naked. He would have undressed in front of this illuminist, and was apparently comfortable not showing himself in an idealized way. At the time, there was no model for documenting that, but they were sufficiently close that he could do this.”

Schwarz’s manuscript reveals a society that treated fashion much like we do today, where one’s wardrobe strongly shapes your outward identity, be it conventional or subversive. “I do think he used fashion to create a persona in the public sphere,” Rublack says. “That also resonated with what his friends wore, and they formed a kind of aesthetic community, one might say. But it was a key expression of the self. We always think of the Renaissance seen in paintings, but this manuscript was a much more alive or authentic way of showing himself day to day on the street as someone with these sensibilities, someone interested in romance or trying to climb socially and politically, and so on. Or even as ‘a bad ass,’ showing yourself as someone who was young and experimenting with identity.

This image from 1523 shows Schwarz driving a sleigh decorated with flax-dance paintings while wearing a hip-length cloak. © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-58).

“I love the images of him on the sleigh being daring,” Rublack continues. “There’s one illustration of Schwarz at 26 where he’s on a sleigh wearing an extraordinary green gown with lots of stripes and colors on it, and the decorations on the sleigh tells us that he’s clearly negotiating a larger sense of whether to adhere to traditional morals or do something different. All that is going on.

“Communicating his emotional moods through the design was very important to him,” she adds, pointing to the era’s novel exploration of masculinity. “A lot of people today think he looks effeminate, but his dress wouldn’t have been understood that way at that time. It was about this new style of delicate, art-loving, subtle manhood that was expressed through an interest in aesthetics, and part of that was fashion.”

Rublack chose this image for the cover of her book, as it epitomizes Schwarz’s romantic self-presentation. © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-67).

For Rublack, the most surprising element of Schwarz’s manuscript was the way it chronicled his futile search for romance. “We didn’t realize that a man like Schwarz was so invested in dressing up romantically,” Rublack says, “with these leather heart-shaped bags and his use of color, as with one of my favorite outfits where he’s all in green, the color of hope.” In some entries, Schwarz is also critical of his appearance, clearly worried about becoming unattractive as he aged.

“He obviously would have had opportunities to marry in his early 20s, but decided to wait,” Rublack continues. “We didn’t expect to find evidence for such a prolonged search for a partner, especially for someone who could afford it.” But as Schwarz reached middle age, he still hadn’t met a romantic match. “This pursuit of love was part of the personality he wanted to project—someone who’s sensitive and subtle,” Rublack says, “but then, of course, all of that broke apart when he actually married.”

At age 41, Schwarz married Barbara Mangold, an acquaintance of the Fuggers who was 10 years his junior, and as Rublack writes, “the wedding had not been the exciting match he had hoped for as a young man.” In fact, the manuscript’s first reference to his impending marriage accompanies an unusual illustration of Schwarz from behind, with his facial expression entirely hidden from view.

The caption above reads, “20th February, 1538, when I decided to take a wife, the gown was made with green trims of half silk.” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-113).

After Schwarz and Mangold were married, his manuscript highlighted less romantic concerns. Throughout the mid-16th century, Augsburg hosted several sessions of the Imperial Diet, a legislative summit for the Holy Roman Empire. “After Schwarz joined the Fugger firm, we have no indication that he traveled outside of German lands, apart from a few business trips to Austria. But of course, the world came to Augsburg for these political summits, the Imperial Diets, in 1530 and after. The emperor would come with a huge international entourage, and that provided another occasion to dress up,” Rublack explains. Several images depict Schwarz wearing a full suit of military armor or formally dressed for other political appearances, and there’s a noticeable shift towards more subdued clothing.

“A key issue for Schwarz was to cope with aging and his new life as a responsible husband and father,” Rublack says. “After Narziss Renner died as a result of plague, Schwarz had to work with a new team of artists, and they portrayed his body in a different way: He suddenly looks a lot larger and weightier. There are more gaps during this period, so there are fewer pictures. Also, the times had changed—Augsburg was now a city divided between Protestants and Catholics. Wars were happening; it was a time of unease. Schwarz’s clothing becomes much more monochrome and less inventive.”

By the end of the manuscript, the portraits slow to only one illustration per year. “Schwarz didn’t know exactly what his experiment would entail,” Rublack says, “which is why I think later it has these gaps. He becomes less sure of it all, but doesn’t want to bring it to an end.” The last few illustrations show Schwarz gradually recovering from a stroke—first with his children tending to his bedside, then with his arm in a sling or tied at his waist, and, finally, in better spirits, walking in the woods with a crown of flowers on his head.

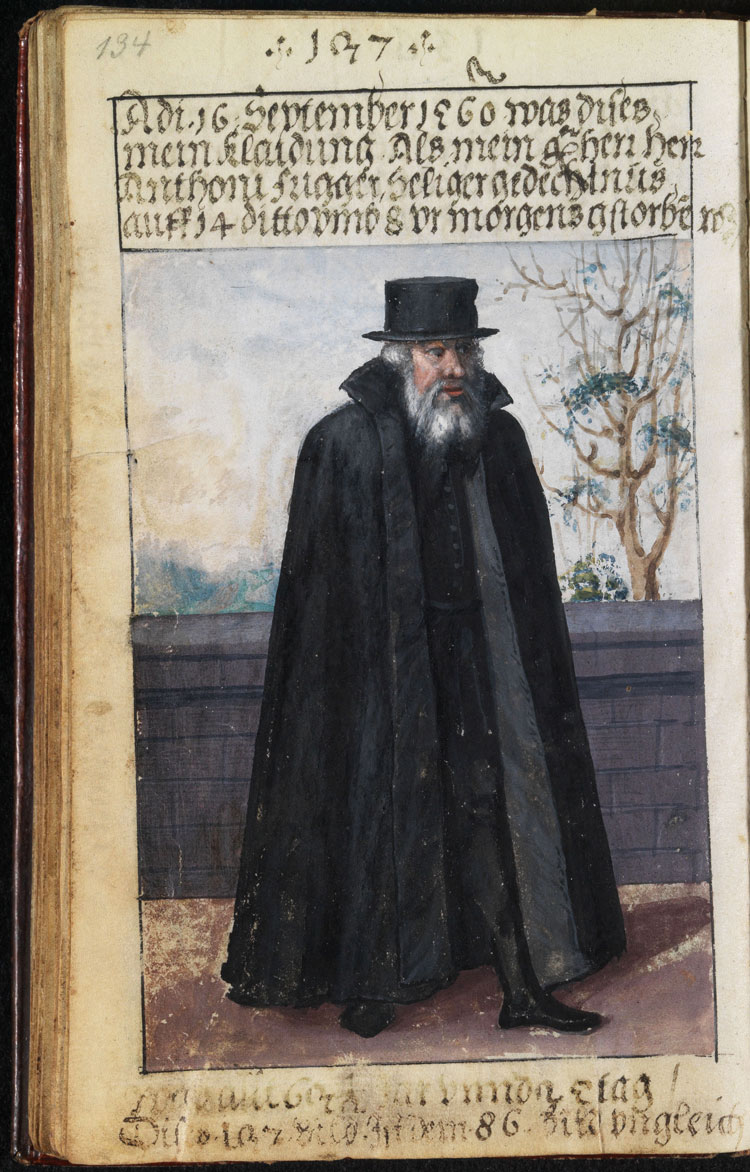

In the manuscript’s final image, Schwarz is depicted mourning his employer and friend, Anton Fugger. “The last image is like an allegory of winter, that sense of death,” Rublack says. “He had invested so much in this project, and the person he worked for, Anton Fugger, had just died. It wasn’t clear what was going to happen with the next generation of his company, and Schwarz was old by the standards of the time. That was the moment he decided to end the project and bind it as a manuscript.” And with that, Schwarz gave us the world’s first book of fashion.

The final illustration shows Schwarz in mourning, with a caption reading, “On 16th September, 1560, this was my clothing, when my gracious master, Herr Anthoni Fugger in blessed memory died on the 14th at 8 o’clock in the morning.” © The Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (Bild-137).

(For further reading, see Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward’s book, “The First Book of Fashion: The Book of Clothes of Matthäus & Veit Konrad Schwarz of Augsburg.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Fashion to Die For: Did an Addiction to Fads Lead Marie Antoinette to the Guillotine?

Fashion to Die For: Did an Addiction to Fads Lead Marie Antoinette to the Guillotine?

When Medieval Monks Couldn't Cure the Plague, They Launched a Luxe Skincare Line

When Medieval Monks Couldn't Cure the Plague, They Launched a Luxe Skincare Line Fashion to Die For: Did an Addiction to Fads Lead Marie Antoinette to the Guillotine?

Fashion to Die For: Did an Addiction to Fads Lead Marie Antoinette to the Guillotine? True Kilts: Debunking the Myths About Highlanders and Clan Tartans

True Kilts: Debunking the Myths About Highlanders and Clan Tartans DrawingsThere’s an immediacy to drawings that is not always present in paintings on…

DrawingsThere’s an immediacy to drawings that is not always present in paintings on… BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of …

BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of … Mens ClothingFor some men, an old concert T-shirt—torn, stained, beloved, and worn prima…

Mens ClothingFor some men, an old concert T-shirt—torn, stained, beloved, and worn prima… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

A Title as Tight as those Leggings. Great One, Hunter !!!

Fascinating piece!