An unnamed inmate at Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas carves a patriotic eagle from hardwood in an art class in March 1943. (Photo by Tom Parker, via the National Archives)

On December 7, 1941, Imperial Japanese war planes bombed an unsuspecting American naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawai‘i, killing 2,403 Americans and destroying 188 aircraft. The next day, the U.S. Congress declared war on Japan, bringing the United States into World War II, which had been raging since 1939.

“When the powers that be take everything away from you, the only thing left is your own creative expression, what you have in your mind.”

Right away, U.S. authorities in California, Oregon, Washington, and Hawai‘i began to round up Japanese immigrants who’d been living peacefully in this country since the turn of the century. Specifically, the feds targeted thousands of men identified as leaders—spiritual teachers, business owners, community organizers, newspapermen, and commercial fisherman who used shortwave radios on their boats—and placed them in Department of Justice prisons around the country. These men in their 50s and 60s, part of the “Issei” or “first” generation, were the heads of households and the figures their communities, wives, and children turned to for wisdom and support in times of crisis. And not one of them had committed an act of sabotage, subversion, or treason.

“In Southern California and the Seattle area, many of the Issei men were out fishing when Pearl Harbor hit,” explains journalist and author Delphine Hirasuna, who is the editor and co-founder of @Issue Journal of Business and Design. “When they brought their boats in, they were immediately arrested. If you spoke Japanese, if you taught a foreign language, if you were the church minister, if you had a successful business, chances are you would’ve been arrested by the FBI and taken away. Their families didn’t know where they were for months, in some cases.”

Homei Iseyama carved teapots, teacups, candy dishes, and inkwells from slate he found around the internment camp at Topaz, Utah. Iseyama had come to America from Japan in 1914 in hopes of attending art school. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

These pre-emptive arrests were a disorienting harbinger of worse things to come. On the West Coast, the Issei, who were Japanese immigrants and not allowed to apply for American citizenship, and the “Nisei,” their American-born children, discovered their bank accounts had been frozen. In these states, curfews were imposed on all people of Japanese descent, and when not going to and from work, they were required to stay within five miles of their homes. Soon, they found it all but impossible to keep a job. Vandalism against Japanese-owned businesses was rampant, prompting the proprietors to hang large “I am an American” signs outside.

“If I were 5 years old and this was happening, it would traumatize me forever, having my dad say, ‘If you see them coming for us, get under the floor.’”

Within six months, all Japanese-born immigrants and Japanese American citizens living on the West Coast and in Southern Arizona—as many as 120,000 people accounting for 90 percent of ethnically Japanese people in the continental United States—were ordered to abandon their homes and report to nearby “assembly centers.” These were usually fairgrounds or racetracks, where they had to sleep in animal stalls, because those were the quickest accommodations the government could muster. After a few months, they would be sent to isolated “relocation centers” or “internment camps” away from the coast and crowded into small, thin-walled and sparsely furnished barracks, where most of them would live for nearly three years or longer.

Being stripped of all their resources made the newly incarcerated extra resourceful. At first, they used every little scrap they could get their hands on to make necessities like chairs, drawers, door signs, Buddhist altars, walking sticks, and shower shoes, as well as doilies and decorations to make their barrack rooms less bleak. But eventually, many of the Issei, who were given fewer responsibilities than their American-born children who could speak fluent English, turned to art as a way to pass the time. Hirasuna first documented these artifacts as artworks made to lessen the emotional pain of being locked up and having their civil rights stripped in her book, The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946.

The day after Pearl Harbor, the owner of this grocery store on the corner of Eighth and Franklin streets in Oakland, California, posted a large sign declaring, “I am an American.” This photo was taken in March 1942, after he closed the store to follow evacuation orders. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, via the Library of Congress)

As Hirasuna points out, these artworks were made by incarcerated people who hadn’t been charged with or convicted of any crimes. In The Art of Gaman, she writes, “All these lovely objects were made by prisoners in concentration camps, surrounded by barbed wire fences, guarded by soldiers in watchtowers, with guns pointing down at them.”

“Gaman” is a Japanese word from Zen Buddhism meaning “enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.” “It basically means ‘Grin and bear it,'” Hirasuna tells me. “‘Gaman’ was the one word that came up during almost every interview I did for the book.”

Hirasuna, who was born shortly after her family returned to California, said her parents tended to speak about their pasts in terms of life before camp and after camp, but they never said anything explicit about their time in these prisons. After Hirasuna’s mom died in 2000, she stumbled upon the art of gaman going through her mother’s things. “I happened to be cleaning out the garage in the house my family moved into in 1949,” she says. “I looked inside a dusty wooden box, and found a hand-carved and hand-painted bird pin, and some other family heirlooms from the 1940s, like watches.”

Art made by the incarcerated—including flower arrangements, wood carvings, and a handmade musical instrument—are displayed at the Arts and Crafts Festival held at Granada Relocation Center in Amache, Colorado, on March 6, 1943. Click to see larger. (Via the National Archives)

Hirasuna was particularly taken with the little wooden pin, no more than ½ inch in height and 1½ inch in width, carved into the shape of a small bird, possibly a sparrow, and then painted and lacquered. Little wire legs hold a tiny wood branch, and a safety pin is glued to the back to make it a brooch. She started wearing it to her job at a San Francisco design studio, where her frequent collaborator, designer Kit Hinrichs, asked her where it came from. Then, he wanted to know what else was made in the internment camps.

The hand-carved and hand-painted bird pin Delphine Hirasuna found in 2000. It was made by her mother, Kiyoko Hirasuna, when she was interned in Jerome, Arkansas, in the 1940s. (From All That Remains, 2016, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

So Hirasuna approached her uncle, Bob Sasaki, who happened to be putting together a display case of things created in American concentration camps for the Lodi Buddhist Temple in Lodi, California. He connected her with other camp survivors and their descendants in the Japanese American community, so she could ask if they had any camp-made objects or art. These items became a springboard for talking about experiences the survivors had suppressed for decades.

“The most rewarding part about working on this book was that talking about the objects let people talk about memories they’d never spoken about before,” Hirasuna says.

For her book, Hirasuna had Terry Heffernan to photograph each memento, and then she returned them to the families. Hirasuna wrote the text, Hinrichs did the design, and then Ten Speed Press published The Art of Gaman in 2005.

Hirasuna estimates that for every piece that survived until 2005, about 10-20 camp artworks had been tossed. “The people who were making them weren’t professional artists, for the most part,” she says. “They considered what they did busywork, a way to pass the time. When the camps closed, a lot of them didn’t know where they were going to live or how they were going to work. So they threw away the objects, instead of taking them back to California, because an artwork would be one more thing that they had to deal with. Everybody made art in camp, so they looked at it and thought, ‘Oh, this is nothing special.'”

Shell brooches and corsages were made by inmates at Tule Lake, California, and Topaz, Utah, who dug up shells from the dried lake beds, sorted them, bleached them, painted them, and arranged them into the shapes of flowers used in place of real-flower corsages at weddings and funerals. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

It’s also likely, Hirasuna concedes, that only the most beautiful examples were deemed worth saving. Later in 2005, when Hirasuna was asked to put together a touring exhibition based on the book, she had to go ask members of the Japanese American community if she could borrow pieces again. “When I was working on the book, I had not even thought about an exhibition,” Hirasuna says. “I had returned everything to the people I borrowed it from.”

The show, “The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942-1946,” toured 15 museums in the United States and Japan over 10 years. In 2016, Hirasuna, Hinrichs, and Heffernan—working together at Studio Hinrichs—published a sequel to the The Art of Gaman book, based on the items uncovered for the exhibition, called All That Remains: The Legacy of the World War II Japanese Internment Camps.

In The Art of Gaman, Hirasuna refers to the prisons as “concentration camps,” which is technically correct, although up until recently, they’ve been more commonly called “internment camps,” in light of the association of the phrase “concentration camps” with the Holocaust and the horrors of the Nazi genocide that led to the deaths of 6 million Jews during World War II.

More than 100 orphaned Japanese American babies, one even as young as 3 months old, were held at Manzanar, as seen in this 1943 photo. (Photo by Ansel Adams, via the Library of Congress)

But ironically, while “the greatest generation” of Americans was overseas fighting the Nazis, the United States had its own dark secret—tens of thousands of American citizens locked up out of racist paranoia.

“There was a move to go through orphanages and foster care facilities to remove Japanese American babies—one as young as 3 months old,” Hirasuna says. In total, 101 orphaned children were placed in the concentration camps. “How could that baby be a threat?”

Also, one only had to be 1/16th Japanese to be incarcerated. “Mixed marriages were not accepted, so if a Japanese immigrant and a white American had a baby, that child might end up in an orphanage,” Hirasuna says. “Then, you have these orphan babies who aren’t even full-blooded Japanese being incarcerated. Which is, to my mind, a form of ethnic cleansing. Not to mention, ailing and disabled elderly Japanese immigrants were being carried out of hospitals on pallets and placed in the camps. How could they be a threat?”

All of this sounds uncomfortably familiar in 2019, where toddlers who don’t speak English are being sent to immigration court alone, and Muslim and Mexican parents are denied entry into the United States to care for their dying children.

An unknown artist incarcerated at Manzanar made this bouquet from pipe cleaners ordered from a catalog and then protected it with a mayonnaise jar from the kitchen. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

At one of the art shows Hirasuna curated, she overheard two elderly Japanese women talking about their memories of camp. “One of them said, ‘My dad was so convinced that if the war went badly, the Army would come in and shoot everybody in the camps,'” Hirasuna recalls. “He began digging a trench under their barrack living quarters, which was just sand under the floorboard. Each day he filled his kids’ little pails with sand and had them discreetly take it out in the yard and scatter it around. He told them if the guards came to shoot them to hide in the trench under the barrack. The other woman said, ‘Your father was so silly,’ and they laughed about it.

“They didn’t overlook anything for reuse. You never threw away an old toothbrush; you turned it into an ornament or something useful.”

“But then I started thinking, if I were 5 years old and this was happening, it would traumatize me forever, having my dad say, ‘If you see them coming for us, get under the floor,'” she continues. “Conditions in camp were not that harsh, but when the unthinkable happens and the entire ethnic population is herded into camps, I can see where you can make the leap to greater tragedy.”

While a number of today’s politicians are ginning up racial resentment that’s been lurking beneath the surface for decades, in the 1940s, war hawks and newspaper columnists tapped into anti-Asian sentiment that had long been simmering on the West Coast: As far back as territorial days, white settlers begrudged any economic success Chinese or Japanese immigrants found, and petitioned for racist laws to hinder the Asian communities in their cities and villages.

Civilian Exclusion Order No. 5, posted at First and Front streets in San Francisco, directed all person of Japanese descent to evacuate the city by April 7, 1942. (Via the Library of Congress)

Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, syndicated newspaper columnists like Henry McLemore and Walter Lippman published hate-filled screeds demanding that Japanese Americans, whom they called “enemy aliens,” be removed from the West Coast. Their government source was Lt. General John L. DeWitt, the leader of the newly formed Western Defense Command based at the Presidio in San Francisco, who believed that Japan could strike a blow that would do “irreparable damage” through a network of secret agents already in the country.

It was a wild, paranoid fantasy, not even remotely grounded in truth, like the idea that United States is currently being “infested” with MS-13 gangs from Central America. “There’s definitely a parallel to what’s going on today,” Hirasuna says. “The reasons people were incarcerated in 1942 had nothing to do with them being a threat.”

And removing Japanese people from the West Coast was also something DeWitt—as well as California Governor Culbert L. Olson and Earl Warren, the Attorney General of California and future Supreme Court Chief Justice—was advocating for in Congressional hearings in February 1942.

On February 19, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War to designate parts of the country military zones, “from which any or all persons may be excluded.” Soon, DeWitt had the whole West Coast declared a military zone, only targeting Japanese Americans for removal.

The authorities search a woman’s luggage when she arrives at the WCCA assembly center in Santa Anita, California, on April 1942. (Via the Library of Congress)

The civilian-run War Relocation Authority was established on March 18, 1942, to manage the relocation of the Japanese American community. The original director, Milton S. Eisenhower—brother of General Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower—hoped to limit the order to men and to bring them to farm communities in the U.S. interior that were starved for laborers. He hoped to simply relocate Japanese Americans away from the coast, instead of putting them in prisons. But governors in states like Utah insisted those evacuees could sabotage their power plants or water supplies. Eisenhower reluctantly agreed to set up concentration camps, writing, “we as Americans are going to regret the unavoidable injustices that have been done.” Unhappy with the direction the relocation was taking, Eisenhower resigned from the WRA on June 18, 1942, and was replaced with Dillon Myers.

“The two camps in Arizona were on Native American reservations. One woman I interviewed said her mother commented that it was like being in a box inside a box.”

Between the capture of the Issei community leaders in December 1941 and the mass incarceration of spring 1942, the remaining Japanese immigrants and their Japanese American children lived in fear of FBI raids.

“This is really nasty stuff,” Hirasuna says. “The FBI went into people’s homes, and anything that ‘looked Japanese’ was suspicious. Afraid, Japanese Americans burned anything with Japanese lettering on it—comic books, records, swords. They didn’t know what would look suspicious to the feds. In the country, like the Lodi-Stockton area where my family lived, farms had outhouses, so a lot of stuff ended up at the bottom of latrines.”

In spring 1942, evacuation notices were posted in Japanese American communities sometimes only a few days to a week before the U.S. military began evacuating them from their residences. Japanese immigrants, who were not allowed to become citizens, had been banned from buying property, so they generally didn’t own their homes. Once they were removed, the landlords would rent their homes and farms to others.

A young evacuee of Japanese ancestry waits with the family baggage before leaving by bus for an assembly center in the spring of 1942. (Via the National Archives)

“It was illegal for the first generation to own real estate,” Hirasuna explains. “If they owned a home or property, chances are it was in the name of their children who were born here, which was the case with my mom’s family. Still, when the government finally said in 1945 it would allow the internees to go back to the West Coast, most people came back. Even if they didn’t have property there, it was their home.

“A lot of them were tenant farmers who were leasing the land, so they lost that farm land,” she continues. “My dad’s family was leasing farm land, but they owned the tractors, and they had planted the crop already when they were ordered into camp. Mom said that the crop was ready to harvest, and they had to leave it behind. They had just bought a new tractor, but they had to abandon it.”

As word of the evacuation order spread, Japanese families had to figure out what to do with their prized possessions they’d scraped and saved to acquire. In the 1969 book Nisei: The Quiet Americans, Bill Hosokawa wrote that when the two-day evacuation notice was posted around Terminal Island off Los Angeles, so-called used furniture dealers “drove up and down the street in trucks offering $5 for a nearly new washing machine, $10 for refrigerators”—a fraction of what the families had paid for them.

Japanese American families holding everything they can carry arrive at the WCCA assembly center, converted rodeo grounds, in Salinas, California, in March 1942. (Via the Library of Congress)

Hirasuna said her parents, and plenty of other young couples in California, looked for a spot to stash their property. “Like a lot of people in Fresno, my parents stored their belongings in the Fresno Buddhist Temple basement,” she says. “Unfortunately, since the entire congregation was forced into internment camps, thieves broke in and stole and plundered what was there. Basically, they came back to nothing.”

They also lost precious companions. “Some people told me a big part of their sadness came from the fact they weren’t allowed to bring their pets with them,” Hirasuna says. “Their animals were either killed or let go. My family left the dog with a neighbor who promised to take care of it. But the dog would wait for them by the side of the road, and while it was waiting, it was hit by a car.”

The reason so many valuable belongings were stored or purged was because the evacuation order dictated internees could only bring what they could carry themselves. “When you read the executive order, what you could carry had to include your bedding and eating utensils,” Hirasuna says. “When you think about packing all that, there’s not a whole lot of room left in your suitcase. So even if they could take paint and other art supplies, they didn’t have the space to do it. They weren’t allowed to take any metal objects, so they couldn’t take hammers and saws. They couldn’t take a radio.”

The restrictions also initially prevented internees from bringing cameras with them, probably to keep them from documenting any injustices or indignities they experienced. But another unintended consequence was that it created a gap in family photos and other such historical documents, which was particularly harsh for families with infants or toddlers.

Suiko “Charles” Mikami studied sumi-e brush painting in Japan before he immigrated to Seattle in 1919. At Topaz and Tule Lake, he painted the barracks as lonely, desolate places. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

“You couldn’t take a camera,” Hirasuna says, “so there are no family pictures of West Coast Japanese Americans for a period of about six months before the WRA relented. My older sister was born at the camp, and her baby pictures only start around six to eight months after her birth, when my family was finally allowed to have a camera.”

It’s hard to imagine how terrifying this all was for the people being incarcerated. Government notices posted on lampposts, telephone poles, and public buildings ordered anyone of Japanese descent to report to Wartime Civilian Control Administration “assembly centers,” which were places like racetracks or fairgrounds, selected because they already had running water, sewage, and electricity hookups. So Japanese Americans had to live in cattle or horse stalls for anywhere from four to six months, as the basic services of the remote concentration camps were still being built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The final construction and remodeling was managed by the WRA, and some young Japanese Americans volunteered to earn money building the camps, hoping to make them as comfortable as possible.

When the Japanese Americans arrived at the WCCA assembly centers, they were stunned to be marched into a barbed-wire enclosed space, surrounded by armed guards, where they had the humiliating experience of being searched, finger-printed, and interrogated as if they were criminals. Their animal stalls only had metal cots and mattress ticking they had to stuff with straw themselves.

Mr. Konda sits on a cot covered by mattress ticking stuffed with hay in his barrack apartment after supper at Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, in June 1942. He shared two small rooms with his two sons, his married daughter, and her husband. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, via the National Archives)

Japanese Americans were being asked to prove their loyalty to the United States. While most of them surrendered peacefully, many felt deeply resentful that they had to do so. Fred Korematsu in Oakland and Gordon Hirabayashi in Seattle were two young men who resisted the “evacuation” and were arrested, which gave them both an opportunity to challenge the constitutionality of the concentration camps. Before the end of the war, both of them had lost their cases at the Supreme Court.

While there were ardent xenophobes leading the charge within the U.S. government, others, like Milton Eisenhower, had their doubts about sending 120,000 Japanese Americans to remote concentration camps. First of all, it was an enormous, resource-consuming undertaking: The government would have to build 10 new camps with barracks, watchtowers, mess halls, toilets, and showers, often in locations that didn’t have roads, much less plumbing. Then, the prisoners would have to be fed.

“Eight of the camps were in deserts; they were so isolated the Army’s engineers had to build roads to get to them,” Hirasuna says. “Even at the time, some government officials thought they were making a huge mistake.” The U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle advised President Roosevelt the camps would disrupt agriculture, tie up American troops and transportation, and create the problem of resettlement.

Barracks under construction near Parker Dam in the Colorado River Indian Reservation in Arizona in April 1942. Parker Dam was a WCCA “reception center” that evolved into the internment camp known as Poston. (Via the Library of Congress)

By August 1942, the Japanese Americans held at the assembly centers were moved to the 10 desolate relocation centers that would be their more permanent prisons: Manzanar and Tule Lake in California; Amache, formally known as Granada, in Colorado; Heart Mountain in Wyoming; Poston and Gila River in Arizona; Minidoka in Idaho; Topaz in Utah; and Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas. At their peaks, each camp held anywhere between 7,000 and 19,000 inmates.

“There was a move to go through orphanages and foster care facilities to remove Japanese American babies—one as young as 3 months old.”

“The situation was similar to Native American reservations and to what’s going at the U.S.-Mexico border today,” Hirasuna says. “The government displaces all these people, and they become dependent on the government. Then, what do you do with them? The camps were built miles away from civilization, the government had to build the sewage systems, power lines, and plumbing. In 1941 dollars, it cost $80 million, which would be billions today, and consumed labor hours of the Corps of Engineers that could have been put toward the war effort.”

“The two camps in Arizona were on Native American reservations,” she continues. “One woman I interviewed said her mother commented, ‘We were fenced in, and we were behind barbed wire on the reservation.’ She said it was like being in a box inside a box.”

A dust storm hits Manzanar Relocation Center on July 3, 1942. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, via the National Archives)

These were miserable places. The hastily built barrack rooms were small, the largest being 20 by 24 feet, which was expected to hold a family of six but sometimes housed more. Often the walls didn’t reach the ceilings, so the rooms were drafty. Army surplus winter coats, which were usually too big for the incarcerated, were distributed to the West Coasters used to mild winters. They had to leave their barracks to use the unsanitary military-style latrines, often walking a long distance to wait in line.

“The FBI went into people’s homes, and anything that ‘looked Japanese’ was suspicious. Afraid, Japanese Americans burned anything with Japanese lettering on it—comic books, records, swords.”

In the deserts, the families had to weather extreme heat, extreme cold, and dust storms that made sand impossible to escape, while in the swamps, they were plagued by humidity and malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Each camp had its own hospital, but even with the Japanese American doctors and nurses recruited to work in them, there would be a shortage of medical professionals and medical supplies. Nearly 6,000 babies were born at the concentration camps, while 1,862 inmates died of illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and tuberculosis.

Every camp had its own kitchen and mess hall, but with several thousand inmates, they would sometimes run out of food. At first, meals were mostly hot rice and vegetables until the prison-run livestock programs got underway. Food poisoning was also a common affliction.

While many white Americans believed that the Japanese Americans being locked up were living large on the government dole while their own resources were being rationed for the war effort, the truth is the incarcerated were asked to sustain the camps themselves, growing vegetables and tending livestock for the food supplies.

A man incarcerated at the WCCA assembly center in Fresno tends a garden he planted there in the summer of 1942 (Signal Corps photo, via the Library of Congress)

The oldest people in camp were generally the Issei men, who came to the West Coast as young men between 1868 and 1907, hoping to make their fortunes and taking jobs as laborers. Thanks to an anti-Japanese fervor that was taking hold in San Francisco and other California cities, the United States and Japan entered an informal “gentlemen’s agreement” in 1907, where Japan agree to deny passports to men wanting to emigrate to America, while the U.S. promised to allow the families of Japanese laborers already in the country—including wives, children, and parents—to immigrate without trouble.

The men who were single sent for “picture brides,” a match-making system that used pictures and family recommendations to pair Japanese men in America with single women in Japan. Right before the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned all immigrants from Asia, passed, Japanese immigrants rushed to request picture brides. By 1942, the first generation immigrants were men in their 50s and older, and their wives, who were often 10-20 years younger. They were outnumbered by the younger generation, the Nisei, who were all American-born, ranging from schoolchildren to young adults in their 20s. The older Niseis’ children were the “Sansei,” or third generation.

“Two-thirds of the people in the camps were American citizens,” Hirasuna says. “Because the first generation was not allowed to apply for citizenship, the citizens among them were born in the United States. Most of the Japanese men who came to America to work, came as bachelors. They had hoped to make their fortune and go home. When it became clear that that wasn’t going to happen, they decided to send for picture brides. There was a huge generation gap between the men and their wives, who came to the U.S. 20-25 years later. Then, they started having children.

Neither the elderly nor infants were spared from Japanese American relocation orders. A grandmother and her youngest grandchild stand outside their family ranch in Santa Clara County, California, in April 1942, just before their removal. (Via the Library of Congress)

Thanks to the large numbers of children, “the average age of people in camp was 17,” Hirasuna says. “And the teens were typical American kids. They loved jazz and swing dancing. By and large, they did not speak, read, or write Japanese. Maybe they spoke broken Japanese to their parents, but they were very American. The kids gave the roads in the barracks names like Benny Goodman Street and Swing Street. When they made arts and crafts, they made popular American characters like Mickey and Minnie Mouse and Donald Duck. The older people who had lived in Japan made things that had more of a Japanese aesthetic.”

The camps completely blew up the familial hierarchy that had been the foundational structure of Japanese American society. “The camps had communal mess halls, and the kids would sit with their friends instead of their families,” Hirasuna says. “It made the Issei men, the ones who were heads of households, feel like they were losing control of their families. And they were. In Japan, the head of household was the final word on everything, and suddenly, you couldn’t even find your kid at dinnertime.”

The War Relocation Authority allowed the English-speaking American-born Nisei to establish some semblance of self-governance in the camps. But the WRA always made the major decisions, and the camp governments were intended as a means of “Americanizing” the incarcerated.

Japanese American boys started playing baseball soon after their arrival at Manzanar in April 1942. (Photo by Clem Albers, via the Library of Congress)

“Another way the U.S. government emasculated the Issei men is that unless you spoke English, you were not allowed to participate in the camp-governing body,” she continues. “So, their kids who were, at most, in their 20s, were suddenly the presidents of their blocks. It was just a slap in the face to their fathers.”

As the camps were expected to be self-sustaining, every adult had a job—anything from working in the kitchen or feeding coal to the boiler to serving as the camp doctor. Work days were long and hard, especially for those working on the camp farms. A factory to make clothes for all of the incarcerated Japanese Americans was established at Minidoka, while factory workers at Manzanar, Gila River, and Poston produced camouflage nets used in the war. Gila River workers made ship models for the U.S. Navy, and Heart Mountain had a silk-screen shop to produce propaganda posters for the military.

These jobs paid a fraction of the standard of living at the time, similar to jobs in American prisons today. In 1942, the average American made $157 a month. “In camp, the maximum pay per month was $19 a month, and that was if you were a doctor or a dentist,” Hirasuna says. “But the average pay was $12 a month. Everybody was supposed to do some kind of work, but they didn’t get skilled-labor pay.” Those who were fortunate enough to have property outside were not making enough to keep up with mortgages, taxes, or insurance payments.

Fruit crates, like the one internee Tsutomu Fuhunago is pictured unloading in 1943, were popular material for hand-carved wood art like bird brooches. (Photo by Ansel Adams, via the Library of Congress)

The incarcerated organized schools, sports, and clubs for the children, as well as sports, martial arts, music and theater performances, poetry readings, social events, and vocational, English-language, and American history classes for the adults. Some of the incarcerated Japanese Americans even began to publish newspapers for their respective camps. Both Christian and Buddhist services were held. “The Nisei did make art, but they also played baseball and threw dances,” Hirasuna says. “The schoolchildren had Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.”

For the children too young to understand what was happening, camp was a great adventure. Both elementary and high school-age kids got to escape the racism they faced daily at American schools. “They got to be captain of the football team and prom king, all these things that they couldn’t have done back home,” Hirasuna explains. Still, their schools often lacked trained teachers, textbooks, scientific equipment, and other supplies. In Tule Lake, students practiced typing on sheets of paper drawn to look like typewriter keyboards.

And the older teens and twentysomethings understood that their civil rights as American citizens were being violated. The incarcerated felt scared and angry. For most Japanese Americans in the camps, surviving on a daily basis was a bigger priority than acting out against their captors, or escaping. Most were intimidated into silence and felt it was safer to “grin and bear it,” but a handful felt emboldened to engage in overt acts of resistance.

Mr. Tokieko’s former neighbors, Effie and Emanuel Johnson, took in and nursed his very sick daughter back to health. Tokieko, incarcerated at the Fresno Assembly Center, built this table as a thank-you gift from the scrap wood and palm branches he found around the camp. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

In the first few months at Manzanar, where most of the incarcerated came from Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, the inmates were deeply divided between pro-WRA and anti-WRA factions. The members of the Japanese American Citizens League were determined to cooperate with the WRA to prove that Japanese Americans were indeed loyal. The opposition, a group of American-born citizens educated in Japan, felt that it was an insult to suggest they’d be disloyal in the first place, and suspected camp administrators were pilfering from the meat and sugar supplies. They saw the JACL leaders as snitches and traitors, whom they marked for death. After the head of JACL in Manzanar was beaten in a surprise attack, the leader of the kitchen workers’ union was arrested, leading to a massive protest at the camp in November 1942. The military police responded by throwing tear gas and shooting into the crowd, killing two and wounding several others. A handful of inmates thought to be too close with the WRA administration also received beatings at Topaz, Jerome, and Poston.

At Tule Lake, Poston, Heart Mountain, and Jerome, some of the incarcerated put together unions to strike and organize work stoppages against deplorable wages the inmates received for their labor. Again, the military police cracked down on them. By July 1943, Tule Lake became the maximum-security camp where all the “trouble-makers” were sent, ensuring the other nine camps operated quietly.

U.S. officials fully expected to face this sort of unrest over the unlawful incarceration of American citizens, so they were open to suggestions on how to head off any stirrings of discontent. Artist Chiura Obata, who’d been an art instructor at UC Berkeley for a decade, deserves credit for convincing U.S. authorities that art-making would have a calming effect on the internees.

A student in Chiura Obata’s still life class works on her painting at the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, on June 16, 1942. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, via the National Archives)

As soon as Obata arrived at Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California—a WCCA assembly center—he requested permission to start an art school in the mess hall. He was allowed to call his friends in the San Francisco Bay Area art community to ask them to donate supplies, and he recruited other incarcerated Bay Area artists to teach. Within a month, Obata had launched 95 classes in 25 disciplines, from figure drawing and sculpture to fashion design and commercial layout. Later, Obata would be sent to Topaz, where he received a beating for being too friendly with the WRA.

“When I’d ask Nisei about it, I’d say, ‘Did your father steal a hammer or saw?’ One woman told me, ‘No. Nobody admits to stealing, but everybody admits to knowing somebody who did.’”

Besides Obata, only a small percentage of the incarcerated were professionally trained or acclaimed artists and artisans. Those included painter Henry Sugimoto; painter and print-maker George Matsusaburo Hibi and his wife, painter and print-maker Hisako Hibi; and architect and furniture maker George Nakashima. The famous sculptor and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi was living in New York City, which was not a “military zone,” but offered to start a craft guild at the Poston, Arizona, camp. However, it took him seven months to convince the guards he wasn’t just another prisoner. White American painter Estelle Ishigo voluntarily evacuated to the Heart Mountain, Wyoming, camp to stay with her husband, Arthur Ishigo.

Beside such notable exceptions, “most of these artworks were done by people without any professional training,” Hirasuna says. “When the powers that be take everything away from you, the only thing left is your own creative expression, what you have in your mind. And so art became in many ways essential to mental survival in the camps, to create something beautiful and say, ‘I made this.’ It played a strong role with the older people. I think the younger people didn’t fight for their identity in that way. They did arts and crafts, but not on the same scale.”

On June 30, 1942, Issei who arrived at Manzanar early busy themselves painting in art class. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, via the National Archives)

What’s impressive when you look through The Art of Gaman is not just how beautiful these objects are, but also the ingenious use of found materials, putting today’s upcyclers to shame. Because the camps were built so hastily, the Corps of Engineers and WRA contractors left piles of scrap wood lying within reach.

“I have pictures of the scrap piles,” Hirasuna says. “There was so much lumber around that people were grabbing it and using it to build chairs and other furniture. Because the Army was still building the camps when the Japanese Americans were moved in, the workmen would discover that their hammers and saws were disappearing. When I’d ask Nisei about it, I’d say, ‘Did your father steal a hammer or saw?’ One woman told me, ‘No. Nobody admits to stealing, but everybody admits to knowing somebody who did.'”

Butter knives from the kitchen, with the help of the furnaces, were turned into scissors, pliers, carving knives, and chisels. To me, a Gen Xer, it’s amazing to see all these things that were made from hand with very little resources. But I have to remind myself that in the time between the Civil War and World War II, Americans were still making many things by hand, building furniture and barns, sewing their own clothes, some even doing their own blacksmithing. Issei men who were born in Japan were likely trained in the art of joinery, which is helpful when you need to make furniture and can’t buy nails.

These pliers and tin snips were made by Akira Oye in Rohwer, Arkansas, who melted down scrap metals like discarded saws, car springs, filings, and butter knives in the boiler furnace and hammered his own tools. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

“Certainly, the first generation of Japanese men came to America as itinerant workers around the turn of the century,” says Hirasuna, who is a Baby Boomer. “They learned to make-do and be ingenious in solving problems. At camp, probably some of them said, ‘Hey, I helped build the railroads, so I know how they use those furnaces to throw coal and forge railroad ties.’ I don’t think our generation could do that. Those were the times when housewives were canning and men repaired their own farm equipment. Everybody knew how to sew their own clothes. If my generation were incarcerated today, I’d be completely lost. I’d have to order from Amazon.”

Any kitchen waste—tin cans, fruit crates, onion sacks, wrapping papers, mayonnaise jars, etc.—would be salvaged to be turned into something lovely. “Originally, their materials were all found and scrap.” Hirasuna says. “For example, one man drew a picture on the backside of the evacuation order, because paper was hard to come by in the camps. They didn’t overlook anything for reuse. You never threw away an old toothbrush; you turned it into an ornament or something useful. Nothing got tossed.”

At most camps, the incarcerated starting crafting out of necessity. “After bringing what you could carry, you got to camp and you suddenly discovered you needed clothes hangers or a chair to sit on,” Hirasuna says. “So they really were trying to just cover their essential needs. Once they’d met their creature comforts, they got more creative and artistic about what they were making.” Eventually, art-making would prove so popular that the camps would host monthly art shows, which were big to-dos for the inmates.

Walking canes made by H. Ezaki at Gila River, Arizona. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

One of the first orders of business was making walking canes. “The roads in and around the camps were not paved, and at the desert camps, the terrain was sandy,” Hirasuna says. “So handmade canes were a big deal. When you saw the men around camp, they always had a stick that they were sanding to make a cane for themselves. At first, they couldn’t even get sandpaper. They had to crush glass and glue it onto cardboard.”

Japanese-style geta shoes, which are basically wooden platform shoes, were another must-have. “The showers, the toilets, and the laundry room were located in a different building along sandy or swampy roads,” Hirasuna says. “The only things your living unit had were a bed and a potbelly stove. People didn’t want to wear their street shoes out there because they couldn’t afford to get another pair. So geta shoes became what you wore to the shower or to do your laundry.”

Because all the barracks looked so much alike, it was easy to get lost, so the incarcerated used the scrap wood to make door signs to distinguish one room from another. Not only were the barracks confusing, they were also depressing. Anything one could do to make these grim accommodations more homey, like planting flowerbeds, became a key to sanity. Hirasuna’s mom, who had two children, an infant and a toddler, made doilies. “I must have 20 doilies that she made in camp,” Hirasuna says. “There are pictures of all these women sitting around, crocheting or knitting.”

Gentaro and Shinzaburo Nishiura made this 5-foot-tall butsudan while incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. They built the Japanese Pavilion for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco and the Buddhist Church in San Jose. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

Hirasuna says that a majority of the Japanese Americans in the camps were practicing Buddhists, and none were able to bring the family butsudan, a piece of furniture that served as an altar. “When somebody dies, the Buddhist church gifts them a new name, which the family put in its butsudan,” Hirasuna says. “You’re supposed to honor it every day.

“It made the Issei men, the ones who were heads of households, feel like they were losing control of their families. And they were.”

“At the time, a lot of Japanese Americans had large butsudans in their homes that they brought from Japan,” she continues. “These were too big to pack in their suitcases and carry. When you got moved into a camp, if you’re a practicing Buddhist, you wanted to have a butsudan in your barrack, especially in that kind of environment, where you felt like you needed to be close to God. So people just made their own out of hollowed-out logs and scrap wood. Someone told me they made theirs out of a cigar box. The most ornate example in my book was made by brothers who were professional wood workers who built the San Jose Buddhist church after they returned from camp. But for the most part, the butsudans made in camp were humble-looking things.”

The art produced at each camp often depended on the natural resources of the location. After the WRA administrators realized that none of the incarcerated could get far on foot, as the camp locations were so deep in deserts or swamps, internees were allowed to wander outside the grounds where they could collect rocks, branches, and shrubs. Tule Lake and Topaz were built on dried lake beds, so the incarcerated gathered shells to arrange into flower brooches or figurines.

Two unpainted pairs of geta by Masataro Umeda in Jerome, Arkansas, and a painted pair by Fumi Okuno in Amache, Colorado. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

At the camps in Arkansas, young men were eager to sign up for firewood-hunting duty. In the nearby swamps, they would saw off cypress knees—in addition to the wood they brought back for the furnaces—because they found beauty in the knobby forms. They would peel off the bark and keep the wood as an abstract natural sculpture called kobu.

“My uncle said, ‘You have to have a kobu in the book,'” Hirasuna recalls. “He brought one over and explained that everybody in Arkansas would go out into the swamps and hunt for great-looking kobu. I showed his kobu to Kit, who said, ‘This is ugly,’ so I took it back to my uncle and said, ‘We’re not going to use this.’ Later that day, he called me up and he said, ‘If you don’t use it, you’re going to just disgrace and anger everybody. This was the biggest thing in the camps. Everybody knows a kobu. Everybody has a kobu.’ I took it back to Kit and said, ‘We have to use this.'”

Hirasuna was surprised to find so many objects were made of wood not found near the camps. But, as it turns out, saws and hammers were not the only things crafty internees swiped. “Someone told me, anecdotally, that when the trains would come in, bringing supplies for the camps, the men who were recruited to unload the pallets would steal the pallets and some of the wood under the pallets,” she says. Taking this wood was just one small act of rebellion and way to assert their autonomy.

Japanese Americans who just arrived at Granada Relocation Center in Amache, Colorado, on August 29, 1942, began to make benches out of the scrap wood construction workers left behind. (Photo by Tom Parker, via the National Archives)

In February 1943, all adults in the concentration camps were required to fill out a loyalty questionnaire, designed to suss out which Japanese Americans could be trusted to serve in World War II. Questions included things like whether one preferred baseball or judo, speaking English or Japanese, practicing Christianity or Buddhism. But the two most important questions were Nos. 27 and 28. Question 27 asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”

And Question 28 was “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization?”

While the survey set off protests in all 10 camps, more than 80 percent of the incarcerated answered both questions in the affirmative. But a small minority found the questions so offensive that they refused to answer. Some of the Issei had a hard time reading English, so the questions were particularly confusing for them. Plus, if they couldn’t become U.S. citizens, what would happen once they renounced Japan?

The artist who made this six-sided wood vase constructed it from a fruit crate and dark and light ironwood found near Gila River. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

The people who answered “no” to both became known as “no-nos” and were removed to the maximum-security camp, Tule Lake, potentially to be “repatriated” to Japan. As a result, that camp’s population—which already had a large number of Japanese Americans who answered “yes” to the questions—swelled to 19,000 in facilities built for 15,000, and discontent only grew among the inmates. Labor strikes and anti-WRA protests led to many of Tule Lake’s incarcerated being beaten by the guards. The camp was placed under martial law for two months starting in November 1943, while all inmates were subjected to searches, curfews, and restrictions on their work and recreation hours.

With the “no-nos” out of the picture, the WRA began to relax its rigid rules and restrictions on the incarcerated in the nine other camps. Then, Japanese Americans were allowed to order arts and craft supplies like pipe cleaners, paints, and brushes from the Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogs.

“When the government realized that the people remaining in the camps were no danger, officials sent the camps some WPA equipment like looms or woodworking tools,” Hirasuna says. “So a lot of the things in my book were made later. Early camp artworks were more crudely done. As the Japanese Americans got access to better materials and equipment, they made finer things.”

In 1943, Hidimi Tayenaka planes a piece of wood using equipment sent to Manzanar from the Works Progress Administration. (Photo by Ansel Adams, via the Library of Congress)

U.S. officials were also starting to understand they’d hurt the country by pulling tens of thousands of people out of the workforce who could fill jobs for the men sent overseas.

“So many Americans were drafted into the Armed Forces that there was a labor shortage,” Hirasuna says. “The government started to offer work furloughs to American-born citizens in the camps to work in Midwestern and East Coast cities and towns, at manufacturing plants and on farms. That’s why Chicago has such a large Japanese population now. If you could find somebody to sponsor you, you could go to college. One of my aunts got a job in Washington, D.C., working for the State Department during the war. It’s like, ‘Wait a second! You said Japanese American were enemies.’ It’s crazy that a person classified as an ‘enemy alien’ could get sponsored out of an internment camp and go work for the government.”

The U.S. also needed as many men as possible to serve overseas. The U.S. Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team was established on March 23, 1943, with 3,000 Japanese American volunteers from the U.S. territory of Hawai‘i—which was under martial law but didn’t have the same sort of concentration camps—and 800 who signed up from the 10 camps on the mainland. Again, it was an absurd ask, considering that tens of thousands of “American citizens of Japanese ancestry” were still being locked up because of their “enemy alien” status. Eventually, men were drafted out of the camps, too. (Although Issei community leaders in Hawai‘i had been locked up immediately after Pearl Harbor, local leaders determined removing all 121,000 Japanese immigrants in Hawai‘i would wreak havoc on the territory’s economy.)

“The irony is, right after Pearl Harbor, young Japanese Americans rushed to enlist,” Hirasuna says. “And at first, they were rejected. But eventually my father and four of my uncles served in Italy. My father was 37 years old when he was drafted, and he had two kids.” The 442nd eventually grew to 14,000 men, and received the most Purple Hearts—9,846—of any regiment of its size in the war. In the end, 33,000 Japanese American men served in the American military during World War II.

An Issei woman incarcerated at Jerome in Arkansas works on a wall plaque she’s decorating with tissue-paper flowers at her night art class in March 1943. (Photo by Tom Parker, via the National Archives)

Once the internees had more ready access to art supplies like paint and brushes, trends took hold in the camps. Making bird pins, like the one Hirasuna found in a dusty box in her parent’s garage, was tremendously popular.

“It was easy to do—easy in the sense that you only needed, like, two inches of wood and a pen knife,” Hirasuna says. “The internees were using the fruit crates that came in regularly, because the edges were the right thickness. Anybody could do it, so it became a fad in all of the camps.”

From the small square of crate wood, the incarcerated would carve and sand the bird form in 3-D relief on the front side. Then they’d paint their bird carefully to get the feather and beak colors just right, and lacquer it. A safety pin would be glued to the back to make it a brooch. To make the perfect wire legs, the artists cut up the mesh wire scrap that was left over from the cage-like screens put over the barrack windows.

Bird pins carved, painted, and lacquered by Himeko Fukuhara in Amache and Kazuko Matsumoto in Gila River. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

“They made very accurate birds,” Hirasuna says “To do that, they needed to get a realistic picture of a bird to copy, from ‘National Geographic’ or Audubon cards.” There was one “National Geographic” issue in particular that featured a bird taxonomy the artists relied on. “I’ll bet you the people in the back-issue office at ‘National Geographic’ probably thought, ‘What the hell?’ with all these people in internment camps writing letters saying, ‘Please, send me that issue.'”

Many of the Issei favored traditional Japanese arts like sumi-e brush painting, ikebana (flower arranging), calligraphy, origami, and haiku writing. Each camp developed its own specialties, too. At Tule Lake, flower pins and figurines were made from shells; at Gila River and Poston, sculptures were carved from ironwood and cactus; at Minidoka, people painted on stones and carved greasewood; at Amache, making miniature landscapes was a popular pastime.

Homei Iseyama, a self-taught artist, carved ornate teapots, teacups, candy dishes, and inkwells out of the slate he found around Topaz. At the same camp, Tani Furuhata ran a class teaching other Issei women the art of making traditional Japanese dolls, using embroidery thread or crepe paper for the hair and pieces of their own kimonos for the clothes. At Heart Mountain, Isaburo Nagahama, a master of Japanese-style embroidery—who was interned at age 75—taught his craft to other internees.

Tani Furuhara made more than a dozen Japanese dolls in Topaz, their poses and clothing reflecting their status in Japanese society. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

Some internees wove cigarette cases and other utilitarian boxes and baskets from waxy onion-sack string. Beautiful inlaid wood vases were made of a combination of the local ironwood and scrap lumber. One craftsman made a shamisen, a three-stringed Japanese instrument, used for the musical performances at camp. Figural sculptures and vessels were whittled and carved, quilts were sewn, and jewelry was patched together from every material imaginable.

“It was hard to go into camp, but it was equally hard to leave the camp simply because you didn’t know where you’re going to go.”

Even scraps from dinner could be made into a lovely wearable. “One of the things that I saw and wanted to borrow was a bone bracelet, but it was too fragile,” Hirasuna says. “I guess the camp must’ve had meat served with the bone at dinner that night. One internee sliced theirs and made a bracelet with the pieces, stringing it together through the marrow. It’s really a charming little bracelet.”

Amateur painters depicted the barracks as barren, empty places devoid of human life, probably hoping to protect the privacy of their follow inmates. Some men got into model building: Surviving examples include a replica of the barracks at Rohwer made of scrap wood and toothpicks, and a wooden scale model of a freighter that brought Japanese people to America. “One man made a working model train out of tin cans and the tracks for it to run on,” Hirasuna says. “You can see the watch parts, bolts, and file-folder tabs he used to make it.”

Edward Jitsue Kurushima, incarcerated in Poston, made this working steam locomotive model with tracks out of tin cans, watch parts, paper clips, and bolts. (From All That Remains, 2016, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

Some Issei artists made such toys and games for their grandchildren to enjoy; others made games for the adults to play. The card game known as Hanafuda was particularly popular. Choji Nakan at Tule Lake produced a 75-card deck for his camp out of electrical insulation board, and they were so beautifully painted they looked store-bought. Word spread, and Nakan was asked to make nine more decks for the other camps.

For the men who were sent off to fight in the war with the 442nd, someone in the family would make him a senninbari, a sash embroidered with the well wishes of exactly 1,000 people. ”It’s a tradition in Japan to make a senninbari, for people who are being sent in harm’s way,” Hirasuna says. “Usually, it’s made of a rice sack. You paint a tiger on it because tigers are courageous and they always come home. Then you add a thousand French-knot stitches, because a thousand years is a very long life. But each stitch had to be put in by a different person. So if you were being sent off to war, you were sent off to war with the good wishes of a thousand people. When men started getting drafted from the camps, these things were circulating all over.”

However, all those beautiful communal well-wishes made have been lost to the racism of the time. “Today, senninbari from this period are scarce,” Hirasuna says. “Someone told me that it’s because the servicemen who took them to war were afraid that their commanding officer would find them and decide they were colluding with the enemy. Despite the fact that these came with a thousand stitches, a lot of men threw theirs away because they didn’t want to risk it. That’s one explanation I heard, and it seems credible to me.”

Issei mothers, like Masuno Sasaki in Rohwer, created senninbari sashes for their Nisei sons being sent overseas to serve in the U.S. Army. These held French knots tied by 1,000 individuals in the community wishing the soldier a long life. (From All That Remains, 2016, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

The Supreme Court ruled on two important cases regarding the legality of the Japanese internment on the same day December 18, 1944. In the first, Korematsu v. the United States, led by resistor Fred Korematsu, the Court declared that the removal of Japanese Americans from the “military exclusion zone” was constitutional. The second, known as Ex parte Endo, had been filed by the Japanese American Citizens League, who had selected a young woman named Mitsuye Endo as an ideal Japanese American citizen to represent the 120,000 incarcerated. In that case, the Court ruled it is illegal to detain loyal American citizens without cause, no matter what their ethnic background is. That ruling opened the door for the release of the incarcerated Japanese Americans.

“They kept silent because they felt a combination of shame, betrayal, and anger. They didn’t want to pass on the bad feelings about living in this country to their children.

A few weeks later, on January 2, 1945, President Roosevelt signed Public Proclamation No. 21, allowing for Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast. Then, the War Relocation Authority put together a plan to close all 10 of the concentration camps within a year. Internees were offered $25 (about $348 today) and train fare. However, most of the incarcerated people had lost their homes and jobs and drained all their savings, making it difficult to leave, so many Japanese Americans stayed in their camps until they were forced out.

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. Army Air Force dropped a uranium gun-type fission bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, the Army released a plutonium implosion-type fission bomb at Nagasaki, Japan, a city about 186 miles away from Hiroshima. These two bombs, the first and only use of nuclear weapons in a war, killed between 129,000 and 226,000 Japanese people, mostly civilians, and effectively ended the war in the Pacific Theater, as the Japanese government agreed to surrender to the Allies on August 15.

“A great number of Japanese people living in America at the time came from Hiroshima,” Hirasuna says. “It must’ve been traumatic to lose their extended families and the remnants of lives they’d led before. Certainly, my parents were traumatized, as both sides of our family were from Hiroshima. Most of my relatives lived in the country outside Hiroshima, up in the hills, so they survived. But my great aunt, who was living in Hiroshima city limits, died in the bomb blast. It was a double whammy—being incarcerated by your new country and then learning it had bombed your old country.”

Choji Nakan painted 75 individual stylized nature scenes on hard electrical insulation board to make a full Hanafuda card game. Eventually he made a card deck for each camp. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

Most of the camps had closed by the end of 1945, a few months after “Victory in Japan”—except for the maximum-security camp, Tule Lake, which closed in March 1946. The Japanese Americans, who were forced to leave, found themselves distressed all over again.

“It was hard to go into camp,” Hirasuna says, “but it was equally hard to leave the camp simply because you didn’t know where you’re going to go. That was when the most Japanese American suicides happened. People didn’t know where they could live or where they could work. There were towns forbidding Japanese Americans from moving back. Bachelor men were the mostly likely to commit suicide because they felt they had nothing to live for.

“When the camps were closing, the Issei sent their Nisei kids on ahead—they called them ‘scouts,'” she continues. “My grandparents sent my uncle to the neighbors in Lodi who were watching their things. At the train station, my uncle said you would have thought the neighbors were waiting for a load of cocaine, they looked so nervous. Vigilante night riders were shooting at—and sometimes burning down—the houses of Japanese Americans. My aunt was pregnant, and she was afraid to be in the house alone, so while my uncle was tilling the fields, she sat with him on the tractor.

Massao Hatano teaches his Issei students the Japanese art of flower arranging, ikebana, at the Jerome Relocation Center in Denson, Arkansas, in March 1943. (Photo by Tom Parker, via the National Archives)

“My dad was still in the Army, serving in Italy in 1945, so my mom took my sister and brother—who were still little kids—on a train from Arkansas to Stockton, California, which stopped halfway for an overnight layover. But they were too afraid to look for a place to stay in a strange town, so they slept in the park.”

As incarcerated families packed their things to return to the West Coast, not knowing where they would be sleeping or working, their arts and crafts rarely made the cut. The impressive ship model made of scrap wood, wire, and string almost didn’t survive.

“When Jerome was closing, the artist didn’t know where he was going to go live,” Hirasuna says. “As he was throwing it away, a fellow internee said, ‘Can I have it?’ He brought it back to California and then donated to a museum. That was the case with a lot of people. It’s like, ‘Where do we put this?’ I don’t know where I’m going to live. For the most part, they thought, ‘Who would want a crepe paper basket or a door sign?’ If they kept it at all, they just thought they’d need to something to remember camp by.”

And even the things that were brought back to the West Coast didn’t necessarily survive to see the year 2000, because the internees and their descendants didn’t think of their craft projects as historically important artworks. “You know how it goes. As you clean up, you think, ‘Maybe I should just toss it out; the kids don’t want it,'” Hirasuna says.

At Manzanar in April 1942, Fugiko Koba tries out a pair of geta shoes while Yaeko Yamashita watches. (Photo by Clem Albers, via the Library of Congress)

When the Japanese returned to the West Coast, most of them had to start over from scratch, and took miserable low-paying work as tenant farmers, gardeners, and day laborers. It was especially hard on the Issei, who were entering their golden years with no way to retire or slow down. The stress of keeping a roof over their heads and food in their fridges prevented them from having the time to indulge in the pleasure of creative expression. “When they left the camps, they didn’t go back to their art,” Hirasuna says. “Even if they liked what they were doing, they didn’t have the time.”

“All these lovely objects were made by prisoners in concentration camps, surrounded by barbed wire fences, guarded by soldiers in watchtowers, with guns pointing down at them.”

Hirasuna, who was born after her family had returned home, says her parents, like most of the Nisei generation, did not like to talk about camp. They were aware they’d been victims of a grave injustice that went against everything America stood for, and they were humiliated about it. They were also afraid of what would happen to them if they spoke up against the U.S. government.

“They kept silent because they felt a combination of shame, betrayal, and anger,” Hirasuna says. “When it came to the next generation, the adults didn’t want to pass on the bad feelings about living in this country and their white neighbors to their children. When I was growing up, I didn’t know what camp was, but I knew enough not to ask.

“As I’m learning more and more about what happened, I feel like I owe them an apology,” she continues. “When I was a little girl, I thought they were so paranoid. Now, I know what they went through, I understand why they acted like they did. They were cliquish. They didn’t mingle with white people. They weren’t rude, but they had discomfort around white people, and I could see that. They didn’t understand why their white friends and neighbors didn’t protest the camps.”

Sadayuki Uno, who had studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland before the war, took up wood carving at Jerome. With a sharpened butter knife, he created caricatures of Adolph Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Josef Stalin, and Winston Churchill out of scrap pine wood. (From The Art of Gaman, Ten Speed/Random House, 2005, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

Photographer Dorothea Lange, who was opposed to the internment of Japanese Americans, had been hired by the U.S. government to document the evacuation and internment, but the military commanders who reviewed her work locked it away when they saw how damning the images were.

Other esteemed photographers were allowed to shoot at the camps, even though all of them—like Lange—were prohibited from taking photos of the guards, watchtowers, barbed wire, and the intense military presence. Ansel Adams’ photographs of Manzanar, which were more optimistic than Lange’s, were published in a book in 1944, called Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans. Even though his book made the “San Francisco Chronicle’s” bestseller list in 1945, the grim story of the incarceration of citizens of Japanese descent was not common knowledge.

“When I was young, I didn’t realize that Ansel Adams had done that book,” Hirasuna says. “I didn’t know to look for it, and we didn’t have the internet. Born Free was out, but for various reasons, the non-Japanese community really didn’t want to know, and the Japanese community didn’t want to dredge it up. So there was a conspiracy of silence.”

Jitsuro Hiramoto was an Issei farmer who was locked up at Santa Fe Detention Center in New Mexico right after Pearl Harbor. There, he looked for branches and roots he could sculpt into forms like cranes. (From All That Remains, 2016, by Delphine Hirasuna, designer Kit Hinrichs, and photographer Terry Heffernan. All rights reserved.)

Members of the Nisei generation were also embarrassed to bring up their experiences in light of the genocide inflicted upon Jewish people in the Holocaust.

“One Nisei woman I interviewed for the book moved to New York City after camp, and because of the number of Jewish people there, she encountered a lot of conversation about the Holocaust and the concentration camps,” Hirasuna recalls. “In conversation with her new friends, someone asked her what she was doing in the ’40s and she said, ‘Well, we were in an internment camp.’ Her friends were just outraged. They didn’t know anything about it, and they said, ‘You let us talk all this time, and you didn’t tell us!’ And she said, ‘I felt like we didn’t suffer enough compared to what happened to the Jews.’ In the face of what happened in Europe, to them, this seemed minor.”

“Everybody made art in camp, so they looked at it and thought, ‘Oh, this is nothing special.’”

While the Issei generation struggled to survive until their deaths, and the Nisei felt ashamed and feared reprisal, it was the Niseis’ children, the Sansei, who had the agency to speak out about the horrors of Japanese internment—once they finally learned about it. They were bolstered by the wave of civil rights movements that were happening from the ’50s through the ’70s. A 2003 documentary by Tadashi Nakamura, “Pilgrimage,” tells the story of Japanese American college students who make the first pilgrimage to Manzanar in 1969. The remaining barbed wire fences and piles of broken dishes made the concentration camp vividly real. After that first trip, it became an annual ritual for those who don’t want to forget.

Minnie Negoro, who was an art student at UCLA before incarceration, makes pottery at the Heart Mountain ceramics plant in January 1943. (Photo by Tom Parker, via the National Archives)

“At the time, the ’60s radicals of my generation were also protesting against the Vietnam War and for civil rights,” Hirasuna says. “As college students, it seemed natural to us to protest against the camps. We were the generation that lobbied for redress in the ’70s, who talked to our parents very angrily like, ‘Why didn’t you protest? Why were you so quiet?’ I remember scolding my parents, and they said, ‘You weren’t there then. You don’t remember what it was like.'”

In 1988, U.S. Congress issued an apology for the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, and passed a reparations law called the Civil Liberties Act that offered $20,000 apiece to the 80,000 living survivors of the camps. After the redress, the Japanese American internment was finally included in U.S. history textbooks, although it was still a whitewashed version of the past. “In the ’80s, our protesting finally paid off,” Hirasuna says. “The part that I regret is that the generation that suffered the most, the Isseis, were all gone by 1988.”

Despite the Redress Movement and all the lessons of World War II, America, it seems, has not progressed as much as we once assumed.

“What’s going on now with the immigrant detention is such a repeat of that past, it shows that we haven’t learned from history,” Hirasuna says. “And it’s going to come back and hit America in the face. It’s bad for the people going through it, but America is going to come to regret it, too.”

(To learn more about the artwork made in Japanese American concentration camps pick up Delphine Hirasuna’s books, “The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946” and “All That Remains: The Legacy of the World War II Japanese Internment Camps.” To learn more about the history of the camps, also check out Ansel Adams’ “Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans,” Bill Hosokawa’s “Nisei: The Quiet Americans,” the website Densho: The Japanese American History Project, and Tadashi Nakamura’s short documentary, “Pilgrimage.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Sex and Suffering: The Tragic Life of the Courtesan in Japan's Floating World

Sex and Suffering: The Tragic Life of the Courtesan in Japan's Floating World

Demolishing the California Dream: How San Francisco Planned Its Own Housing Crisis

Demolishing the California Dream: How San Francisco Planned Its Own Housing Crisis Sex and Suffering: The Tragic Life of the Courtesan in Japan's Floating World

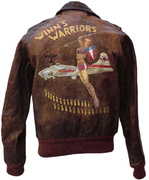

Sex and Suffering: The Tragic Life of the Courtesan in Japan's Floating World WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Japanese AntiquesJapan, with its history of seclusion, has long fascinated Westerners. When …

Japanese AntiquesJapan, with its history of seclusion, has long fascinated Westerners. When … Fine ArtFor as long as there have been civilizations, humans have made art to inter…

Fine ArtFor as long as there have been civilizations, humans have made art to inter… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article!

Absolutely fascinating. I’ve never heard anything specifically about their internment before this.

Thank you, I actually found a small box of wooden carved items. As I studied it, I saw my Great Uncle’s name carved in the back with the word “Gila”. Then, I started to see the carved bird brooch had a safety pin on the back and other beautifully crafted small wooden pieces. I found it along with an odd doll with handmade clothes, and now I see in this article, these are items of joy and art most likely made by my grandmother and her brother while in Gila. Thank you so much for your article to help me see.

Enjoyed the article very much. It is important that these events are remembered. Too often we think that “it can’t happen here”. A prefect example of a real emergency being used as an excuse to violate the rights of American citizens.

I didn’t appreciate the completely unconnected political commentary on illegal immigration.

An unnecessary, unrelated and unwelcome distraction from an other wise great article.

Amazing article! So much more information than other ones I’ve come across. Thank you. We needs to have more diverse and true information.