This article focuses on silversmith Samuel Drowne and his involvement in the American Revolution and U.S. politics. It also provides information on the other silversmiths in his family. It originally appeared in the September 1940 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Undoubtedly the name of Samuel Drowne is as well known as that of any of the early silversmiths of Portsmouth, N. H., but locally, at least, it is more generally remembered because of the prominent part its owner played in the affairs of his community during the period of the American Revolution and in the years immediately thereafter.

Spoons and Sugar Tongs by Samuel Drowne: He was the first of his family to follow the silversmiths' craft in Portsmouth. His dates were 1749-1815. The spoon identified as Number 5 is the earliest. It was made for Captain Lear, father of Colonel Tobias Lear, secretary to General George Washington, and bears the Lear crest. Numbers 2 and 3 are excellent examples of Drowne's "feather-edge" work. They, and Number 1, were made for the Treadwell family of Portsmouth. Number 9 has been reversed to show one of his known marks, "S. Drowne" in rectangle.

Like many other American silversmiths of the time, he was an ardent supporter of the patriot cause and, in fact, he was concerned in an affair which, since it antedates the fights at Lexington and Concord, is considered by many historians as marking the true beginning of the Revolution.

Early in December, 1774, a rumor became current in Boston that the British intended to send troops to occupy Fort William and Mary at the mouth of Portsmouth Harbor. On the thirteenth of the month, Paul Revere galloped to Portsmouth with letters to the Committee of Correspondence there reporting this expected move.

The following evening a party of several hundred men from Portsmouth and neighboring towns went down the river in boats and, in spite of the fire of the small garrison, landed, stormed, and captured the fort. As it turned out there were no casualties on either side, a happy chance which may explain why this exploit has not achieved greater prominence. The originator and one of the leaders of it was Captain Thomas Pickering, Drowne’s brother-in-law, and the silversmith was a member of his company.

The principal object of the patriots in this affair was to secure the powder stored in the fort before the British troops could get it and upwards of four hundred barrels of the precious material were taken and secretly removed upriver to places of safety. This part of the program was engineered by Drowne and he arranged it so successfully that the authorities were unable to recover a single barrel. Later, some of this powder was used at the Battle of Bunker Hill where, it would seem, there was, unfortunately, not enough.

Samuel Drowne was a member of an interesting family to which Shem Drowne of Boston, a prominent coppersmith, also belonged. Leonard Drowne, the first of the name in this country, settled near Portsmouth about 1670, but ultimately the family removed to Rhode Island.

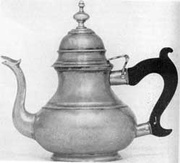

Beaker by Samuel Drowne: Other pieces of silver than spoons and kindred flatware for table use are comparatively rare, although this beaker is evidence that he did make pieces of hollow ware.

The silversmith’s father, also named Samuel, was a grandson of the original settler. He was first a minister of the Calvin Baptist denomination, but later became an Independent Congregationalist preacher and in that capacity was called to Portsmouth in 1758.

Although devout Christians, the members of his flock, being seceders from the established churches, were not highly regarded; commonly they were contemptuously referred to as “New Lights.” In fact, Governor John Wentworth of New Hampshire issued a special edict permitting all ministers in the Colony to perform the marriage ceremony “except one Drowne.”

Samuel, the silversmith, a son of this preacher, was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1749, and died in Portsmouth in 1815. He married Mary, a daughter of Captain Thomas Pickering, one of the largest landowners of Portsmouth, a prominent citizen and a military officer who was killed in battle with the Indians at Casco to the eastward. The Captain Thomas Pickering of the Fort William and Mary exploit was, of course, a brother of the silversmith’s wife. He was a captain of privateers and was killed in 1779 during the capture of a British letter of marque, a vessel much more powerful than the 20-gun ship Hampden, which he commanded.

A few months after the capture of the fort, Samuel Drowne was placed in charge of the leading Tories in his neighborhood to see that they conducted themselves discreetly. In 1778 he was a member of Colonel John Langdon’s Company of Light Horse, an organization especially formed from among the gentlemen of Portsmouth, to assist in the operations in Rhode Island, and was with it during the attempted capture of Newport.

In 1789, Drowne was one of the Committee of Twelve appointed to arrange for the reception of President Washington on his visit to Portsmouth and he further served as a selectman of his town in 1799 and 1804. He was arrested and carried to Exeter for trial in 1795 for alleged participation in riots arising from dissatisfaction with Jay’s Treaty. He had then been a deacon for many years, and the spectacle of this dignified gentleman in the dock inspired a great deal of amusement. However, his detention was easily shown to have been a mistake; he had merely been passing by at the moment of the disturbances.

Spoons by Thomas Pickering Drown: He was the elder son of Samuel Drowne and. along with his younger brother, Daniel P., also a silversmith, dropped the final vowel from the family name. Spoon Number 1 is too early in style for this craftsman's period. His dates were 1782-1849. This spoon is one of a half dozen that he made to match a set of spoons made by his father (see Numbers 2 and 3 in illustration of Samuel Drowne spoons). Number 2 has been reversed to show his mark, "T. P. Drown" in rectangle. The coffin-shaped handles of Numbers 2 and 3 may be considered the earliest work of this silversmith, while the bright-cut spoon, Number 4, is a decorative treatment also used at times by his father, from whom he presumably learned engraving as well as silversmithing.

The silversmith lived on the southern side of what is now State Street, not far from the waterfront, and, as was the usual practice at the time, he had his shop in the same building. His spoons and flatware are not too difficult to find, but pieces of hollow ware by him are exceedingly scarce. His best known mark is “S. Drowne” in a rectangle with shaped ends. He also used “S.D.” capitals in elongated oval.

While the best-known silversmith of the family, Samuel Drowne, was not the only member of it to follow this profession. His brother Benjamin, 1759-1793, of Portsmouth also, was a silversmith. Since he died at a comparatively early age, examples of his work are quite rare and, practically speaking, are confined to spoons.

Like his brother, he made a good marriage, his wife being Frances, a sister of the Major William Gardner, whose name is so familiar to visitors to Portsmouth through its connection with the beautiful Wentworth-Gardner mansion, one of the finest Georgian houses in the country.

Benjamin was also a vigorous supporter of the patriot side during the Revolution and in 1780 was on the staff of Colonel Thomas Bartlet’s regiment of New Hampshire militia. His name is omitted from many lists of silversmiths, but he used the mark “B. Drowne,” capitals in rectangle, and possibly also “B. D.” capitals in rectangle. His house and shop were diagonally across the street from those of his brother.

Samuel, the silversmith, had two sons who followed in their father’s footsteps. This younger generation dropped the final “E” from their surname. The eldest was Thomas Pickering Drown, 1782-1849, whose mark, “T. P. Drown,” capitals in rectangle, is generally familiar. He was prominent in local affairs and in 1817 abandoned his silversmithing to become town clerk, an office which he held until 1826. Then for ten years he was connected with the Portsmouth branch of the United States Bank; but, with the abolishment of this institution during Jackson’s administration, he seems to have returned to his original trade and then possibly worked in Newburyport for a few years, although this has not been verified. His early work closely resembles that of his father, but, apparently, is not as highly regarded.

Daniel P. Drown, 1784-1863, the other son of Samuel, is listed as a silversmith as late as the Portsmouth directory for 1860-1861, but it is doubtful if he ever worked independently, since no pieces of silver with a mark which could be his have been recorded up to the present time, although, of course, it is possible some exist.

Sword with Scabbard by Samuel Drowne: The silver hilt, that ends in a bird's head, and the mounting bear his mark. It was made circa 1775. The scabbard, as was general at this time, is of finely tanned leather. The blade was probably a European import.

Undoubtedly, however, he worked with his father in his early years. During the War of 1812 he was a lieutenant of New Hampshire troops; then he was deputy sheriff until he succeeded his brother as town clerk in 1826, an office he retained until 1832. Two years later, when serving as a selectman of the town, he was appointed Collector of Customs for the Portsmouth district, retaining that office until 1841, when he became connected with the railroad. He was afterwards a justice of the peace, and the Commissioner for the State of Maine in New Hampshire. Thus, he could have had but little opportunity for following his trade, but it may be that for a few years prior to his death he did so.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

William Cario, Father and Son, Silversmiths

William Cario, Father and Son, Silversmiths

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time William Cario, Father and Son, Silversmiths

William Cario, Father and Son, Silversmiths Silver in the World of Washington Irving

Silver in the World of Washington Irving Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I am a descendant of these Drowns. Is there any other information that I accessible?

Thank you,

James Drown

I am also a descendant of the Drown/Drowne family…I have quite a bit of information and photos, that I’d be willing to share…my email address is wendeelouhew@gmail.com.

I am also a descendent of Samuel and Shem drown and i am trying to start a genealogy background.

I am also a decendent of Samuel Drowne was hoping for a little info on how I could purchase a few spoons to pass down to family members?And if you knew the location of Samuels. shop. Are there any sketches or portrates?

To the three people listed above – contact me at jaydee@arvig.net to see where our family trees come together.

Thanks

James Drown

There are some worthwhile links to Shem Drown in Wikipedia; also in the History of Hudson NH, where he lived for many years and deeds to children are mentioned; finally Johnston’s Vital records of Old Bristol and Nobleboro. My ancestor bought land from Drown at Bremen, Maine.

My great grandfather. Stephen Drown of Wakefield N.H. And nearby towns

My Grandfather. Edgar Ira Drown. Also of Wakefield N.H.

My Uncles, Stephen Drown. Living in Enterprise Alabama

William F. Drown. Sanbornville N.H.

Paul Drown. Oregon.

My three uncles are still living, , as are my Aunts, Evelyn, Margaret, and Millie. ( Drown girls)