This article discusses the introduction of garden furniture in the 18th century, which was fueled by the new view of the garden as an outdoor living area, and notes the evolution from wooden furniture to wrought-iron pieces. It originally appeared in the June 1941 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antiques collectors and dealers.

An Englishman’s house may be his castle, but his garden has long been first in his affections. In fact, according to John Parkinson who laid down the principles of garden planning in the early 17th Century, the very location of the house was contingent on the benefits that might accrue to the garden.

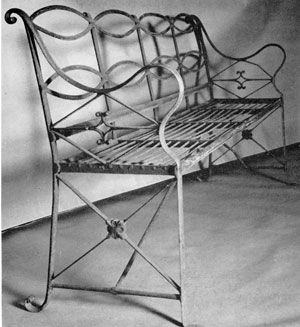

A Regency Wrought-Iron Bench: Made about 1810, the curved arms, back formed of two elements of serpentine curves, and the diamond-shaped and diagonal bracing members below the arms are decorative, reflecting this style as executed in wrought iron.

“The house,” he stated, “should be on the north side of the garden — to safeguard it from many injurious cold nights and dayes, which else might spoyle the pride thereof in the bud — Having the fairest buildings of the house facing the garden the roomes abutting thereon shall have reciprocally the beautiful prospect into it.”

This was sensible advice and, like most pronouncements set down in books, was nothing new. Nearly a century before, Lawrence Washington had located his Sulgrave Manor, home of the Washingtons in Northamptonshire, England, in the selfsame manner, thus emphasizing the important relationship between outdoor and indoor living quarters.

Gardens were taken as a matter of course and commented on freely by both of the great 17th-Century diarists Pepys and Evelyn. The former walks in his father’s garden in the country and picks and eats grapes; he walks and talks with the architect Hugh May and discusses garden planning and the general excellence of English gardens. Later, the garden also serves as a hiding place for his gold when the Great Fire and the threat of the Dutch Fleet make his London house none too safe a spot. The less entertaining but more verbose diary of Evelyn is full of descriptions of both English and European gardens.

A Sheraton Garden Bench in Wrought Iron: The lines and design in this piece were clearly inspired by those of the sofas by Thomas Sheraton.

One looks in vain, however, in these 17th-Century glimpses of the Englishman in his garden for any mention of garden furniture as we know it. He walks and talks with his friends, takes pride in his vineyard, his “orangery” and his statues, if any, but there is no talk of sitting. Also, since tea was not yet the national drink, but sampled tentatively for its supposed medicinal qualities, there was no lingering over the tea table. It is the walks that are emphasized during these years.

“Visited one Mr. Tomb’s garden,” wrote Mr. Evelyn in 1654, “it has large and noble walks, some modern statues, a vineyard, planted in strawberry borders, staked at 10 foote distances.” Twelve years later Mr. Pepys remarks smugly: “We have the best walks of gravell in the world, France having none, nor Italy.”

Hepplewhite Side Chair: The lines are very restrained and reflect the Adam design. The seat is circular, the back and arms are U-shaped curves, and the three legs have a cabriole curve and are strengthened by a three-branch stretcher.

With the 18th-Century, household furnishings became more comfortable and plentiful. Consequently, the outdoor living room reflected the change and garden furniture made its appearance. The first of it was made of wood — probably oak. Later, teakwood from obsolete Indian merchant ships formed the material for tables, benches, chairs, and kindred pieces. This practice carried down to modern times. And as recently as 1938, garden furniture made from teak decking plank removed from scrapped battleships and merchant marine vessels was advertised in various English magazines.

Meanwhile, Sir Christopher Wren had already shown how wrought iron could be put to architectural use. As the beauty of it caught the popular fancy, wrought-iron gates came into use, then fencing, and finally garden furniture. This use of wrought iron gained impetus also through the migration of Jean Tijou from France to England about 1689. He was introduced to Queen Mary, who took a keen interest in laying out her new gardens. As long as she lived, this craftsman in ornamental wrought-iron architecture had her patronage and that of King William. He introduced the use of rosettes and rich embossings.

An Armchair in Iron: In design, this is probably a Chippendale-Hepplewhite transition piece. The front of the legs and back are nicely reeded and it has small, simple paw feet.

Within a year after the accession of William and Mary, Tijou had set up forges at Hampton Court, and rendered his bill for six iron vanes “finely wrought in Leaves and Scrolleworks, £80.” His bill also itemized the cost for the rich balcony to the water gallery, the queen’s abode.

Iron as a material for furniture was used as early as the middle of the 13th Century, when Edward the First presented three iron chairs adorned with human heads for the use of the precentors in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Wrought-iron garden furniture came into vogue in England during the first half of the 18th Century. Pieces made included settees, chairs, flower stands, tables, and tree benches. These began to be used in the gardens of great estates, in those of manor houses and other lesser dwellings about the time Thomas Chippendale was designing furniture in the “Chinese conceit.”

A Lyre Bench in Adam Simplicity: Made circa 1795, it typifies the grace and restraint of that classic style, but also employs serpentine curves for the back and bold outward curves for the arms. The transverse slats of the seat and the arms are unusual.

Makers of such pieces ranged from local blacksmiths and decorative workers in wrought iron to the craftsmen of Sheffield and Birmingham. In the main, the general outlines followed those of the master designers, Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton. The Brothers Adam also made some designs for their country seat jobs. Both formal and naturalistic gardens were so furnished; some of them were famous, such as Horace Walpole’s garden at Strawberry Hill which was equipped with truly remarkable iron furniture.

This adapting of designs commonly associated with indoor furniture to that of the more durable iron for the garden indicates how much of a real living room the English garden was and still is. In America this has been a slow and reluctant growth; but now, in increasing numbers, Americans are being coaxed off their piazzas and initiated into the pleasures of the smooth turf, flower-bordered walks and sheltered nooks that make up a well-appointed garden for everyday living.

A Garden Bench in Hepplewhite Style: The cresting members of the back, the use of reeding and the small paw feet are its decorative features.

With it, collectors are turning an acquisitive eye on antique wrought-iron furniture. Most of the existing examples date from 1780-1790. And because of the medium in which it was produced, it is rather hard to differentiate between the style designs of Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton.

Existing pieces are generally all called Sheraton, because the decorative detail and outline most nearly approximate his designs. These graceful chairs, benches, tables, and the like, hand-wrought and with decorative detail laboriously formed and cut, surpass in beauty any modern, machine-made piece of outdoor furniture. The contrast between it and the degenerate form of the Victorian period, as expressed in the cast-iron seats and chairs found in cemeteries, is also marked.

The best collection of antique wrought-iron garden furniture is or was in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In this country, fine examples are to be seen at Winterthur, Mr. H. F. du Pont’s gardens; at the van Buren gardens of Newport, Rhode Island; and those of other fine estates.

An 18th-Century Tree Seat: It was made in two parts to surround the trunk. This is a piece that was developed in England. The decoration was achieved by reeding and the use of well-shaped paw feet.

In America of the Colonial period, there was some making of garden furniture, gates, balconies, and kindred things. This, strangely enough, was not in New England, New York, or the Jerseys, where the best and most productive iron mines had been established. Instead, Charleston, South Carolina, was the focal point. There, in the center of a region given over to agriculture — rice, indigo, and long staple cotton were the crops of the great plantations — wrought-iron gates, grills, balustrades, and garden furniture were produced for the pleasure of the plantation owners.

Most of these examples disappeared during the Civil War. But from what has survived, the blacksmiths of Charleston must have been craftsmen of a high order who appreciated design and also had the working skill to translate such stylistic impulses into actual pieces. Where these workmen came from or what became of them is not recorded. They disappeared.

But in the early Victorian years of the 19th Century, the lawns and cemeteries of the United States practically bristled with chairs, settees, tables, fountains, and animals of cast iron. The style and technique of execution was different. From design, these American ornaments were native.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Wind Power: How the 19th-Century's Greatest Shipbuilder Opened the Pacific

Wind Power: How the 19th-Century's Greatest Shipbuilder Opened the Pacific Mysterious Railway Posters Depict the Dreamy Allure of Deco-Era Japan

Mysterious Railway Posters Depict the Dreamy Allure of Deco-Era Japan Quest for the Pez Holy Grail: International Smuggling Meets Father-Son Bonding

Quest for the Pez Holy Grail: International Smuggling Meets Father-Son Bonding Vera Neumann, the Woman of Many Scarves

Vera Neumann, the Woman of Many Scarves Stuck on Comic Character Pinbacks

Stuck on Comic Character Pinbacks Benches and StoolsStools, generally defined as seats without backs, are among the earliest ty…

Benches and StoolsStools, generally defined as seats without backs, are among the earliest ty… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.