In this modern age of political polarization, we Americans increasingly surround ourselves with friends, neighbors, and news sources that reinforce our worldviews rather than challenge them. As we spend more of our days online, such divisions are heightened by algorithms that feed on our unchecked desire for affirmation, conveniently hiding opposing perspectives. But amid these isolating echo chambers, the success of political pinbacks offers a small beacon of hope—a quaintly analog way of voicing opinions on touchy topics that’s survived more than a century of civic turmoil, and will surely outlast the current siren call of social media.

“Ronald Reagan’s ‘Let’s Make America Great Again’ slogan is popular again, though the person using it today thinks he came up with it.”

From discreet lapel pins to oversized buttons on purses or backpacks, pinbacks invite conversation by declaring potentially controversial viewpoints to complete strangers. Savvy politicians first adapted tintype and ferrotype photos for their campaign pins in the 1860s, and after the debut of celluloid buttons in 1893, these plastic-covered pinbacks soon dominated the market, starting with the 1896 presidential contest between Republican William McKinley and Democrat William Jennings Bryan. Since then, they’ve been embraced by everyone from grassroots coalitions to military groups, from rock stars to corporate advertisers, with messages ranging from innocuous to abrasive, from silly to serious.

John Aisthorpe, who started acquiring pins during the Vietnam War era, regularly sees new buttons emblazoned with vintage slogans and iconography, reinvigorating old causes for a new generation of engaged citizens. Since his adolescent introduction to politics, Aisthorpe has built a vast collection of pins, particularly related to the social and political movements of the 1960s and ’70s, which he posts on Show & Tell under the name PoliticalPinbacks. “Today, I have 2,000 to 3,000 that are displayed and probably another thousand or more in boxes,” Aisthorpe says. “I’ve kind of become a button glutton.” Despite the unchanged, old-fashioned design of most buttons, Aisthorpe says he often receives comments on their growing relevance today. We recently spoke to Aisthorpe about his wide-ranging pin collection and the perils of a political-memorabilia habit.

Top: A group of Americana pinbacks from Aisthorpe’s collection. Above: Several of Aisthorpe’s antiwar buttons, circa 1967-1971. (Click to enlarge.)

Collectors Weekly: How did you first become interested in pinbacks?

John Aisthorpe: My neighbor, Jim Weatherbe, had a large collection hanging on the wall near his pool table. His burlap-covered board was about 16 feet long by 4 feet tall and completely covered in pinback buttons. As a young boy, I would stare in awe as one button after another grabbed my attention.

My first button was a simple peace symbol given to me while attending an anti-Vietnam protest. I would pick up others now and then at flea markets or antiques stores, but before the last 25 or so years with the Internet, you didn’t see them too often except at the American Political Items Collectors’ (APIC) shows.

A 1965 peace-symbol pin by Larry Fox for an anti-Vietnam War police action.

The peace symbol was designed in 1958 by artist Gerald Holtom for the British group Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), which used it on signs and banners during the Easter-weekend protest march from London to Aldermaston, where nuclear weapons were stored. He based the symbol’s design on the international semaphore alphabet. This system uses flag signals in place of letters like a code. The letters “N” for “nuclear” and “D” for “disarmament” make the left and right branches, with the vertical line representing the person making the signals.

Collectors Weekly: What do you find compelling about pinbacks?

Aisthorpe: Many pins show a little snapshot of history, and I love that about them. A few also capture personal memories, so when I see them, I can’t help thinking, “Oh, I remember that.” They give you an instant flashback to where you were, who you were with, what you were doing—maybe one was picked up attending a concert, or another at a space-shuttle launch.

Aisthorpe’s complete set of the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine buttons from 1968.

Collectors Weekly: What was your involvement in the protest movements of the late 1960s?

Aisthorpe: I was a bit young for most of the war, so I wasn’t too involved, but I did tag along with some older neighbors to a few protests. At the time, I didn’t know where we were going but from all the brightly painted houses, I’m pretty sure it was Ann Arbor, Michigan. To this day, it’s the only town around with that many purple and orange houses.

We protested to support our troops; it was our way of trying to get them home alive. It was unbearable the way so many were treated once they finally got home. I’ve hugged some veterans and shared drinks with them, and I would never think of spitting on one. When I was about driving age, the age I could have gotten more involved, I was disabled, so I wasn’t going to protests or anywhere else.

In this 1971 photo by by Warren K. Leffler, several anti-Vietnam War protesters wear political buttons during a march at the Justice Department in Washington, D.C. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

Collectors Weekly: During the 1960s and ’70s, were specific artists or organizations known for their political buttons?

Aisthorpe: There were many protest groups who put their views on buttons—from the early ’60s with the Free Speech Movement (FSM) to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and, later, the Veterans for Peace, the Fifth Avenue Vietnam Peace Parade Committee, and the Yippies.

Larry Fox, who was known as the Button Man for his business, Fox Buttons, made pins for most of the protest groups beginning in 1963 at Hofstra University through the end of the war and beyond. In 1963, Fox made the “Vietnam for the Vietnamese” button for the Student Peace Union (SPU) and the “One Man One Vote” button for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). He had personal relationships with most of the counter-culture leaders and they trusted him. I have many buttons Fox made and still buy from him today.

Three buttons designed by Larry Fox in the late 1960s.

Collectors Weekly: Were pins successful in spreading awareness of certain issues?

Aisthorpe: Pinbacks were very successful for many social issues and civil rights issues—from the Women’s Liberation Movement and the Free Speech Movement to AIDS awareness, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter. It’s hard to say what impact they had, but the text of buttons worn at protests were often used as antiwar chants, like “Hell no, we won’t go!” and “1-2-3-4 W.D.W.Y.F.W.,” which stood for “1-2-3-4 We Don’t Want Your Bleeping War.”

This button from the early 1970s features a popular antiwar chant.

They must have had some effect. The largest protest of the Vietnam War took place on Nov 15, 1969, with more than 500,000 people in Washington, D.C., alone, and speeches by antiwar politicians including representatives like Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern, who were Democrats, and Charles Goodell, a Republican. It also included performances by Peter, Paul and Mary; Arlo Guthrie; and Pete Seeger, who led the crowd in the singing of John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance.” With his voice carrying above the crowd, Seeger interspersed phrases like “Are you listening, Nixon?” and “Are you listening, Pentagon?”

After the protest, Nixon said, and I quote: “Now, I understand that there has been and continues to be, opposition to the war in Vietnam on the campuses, and also in the nation. As far as this kind of activity is concerned, we expect it; however, under no circumstances will I be affected whatever by it.” But how could he not have been? Unfortunately, he expanded the war less than a year later, and that sparked even more protests and, sadly, the Kent State shootings, which ignited even more. The whole thing was out of control.

Collectors Weekly: How has your collection shifted since the ’70s?

Aisthorpe: My collection has gone full circle. I started with the Vietnam era, then concentrated on Robert Kennedy, NASA, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Guardfrog. Now, I’m back to Vietnam again. I have all kinds of buttons—one was used at a concert as a backstage pass, others are from state fairs, and some are hunting and fishing licenses. I still seem to go for the anti-establishment buttons, so I guess that’s deeply ingrained in me. I also like both black-and-white and colorfully illustrated buttons, plus I have a weak spot for limited editions.

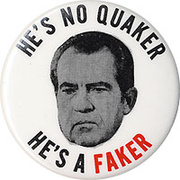

Collectors Weekly: Is it common for political pins to play off historic imagery or slogans?

Aisthorpe: Surprisingly, not that many historic images are used on political buttons, but a few images are used over and over, like Uncle Sam, the U.S. Capitol building, or the Presidential Seal. Some slogans have been around from the start and are not likely to ever disappear. George Washington had a brass button that read “Long Live the President.” Buttons reading “Peace and Prosperity” have been made for more than 100 years. Even Ronald Reagan’s “Let’s Make America Great Again” slogan is popular again, though the person using it today thinks he came up with it.

Three buttons for the Fifth Avenue Vietnam Peace Parade Committee from the early 1970s.

Collectors Weekly: How do you feel about purchasing buttons with messages you disagree with?

“They were made to spark emotion and start conversations. Sometimes it gets a bit overheated, but I try not to take it personally.”

Aisthorpe: To build a complete collection, I have buttons that show views from both sides. For example, most of my Vietnam buttons feature antiwar designs, but I also have buttons in support of the war, and I even have a few National Liberation Front buttons made by the Communists. There are very few topics that I so strongly disagree with I won’t own a button supporting them.

One of the larger misconceptions is the idea that if you own a button, then you must share the view of that button. Often, if you show an anti-X button to someone they will assume you’re just an X-hater or a Y-lover. But it’s all good, as they were made to spark emotion and start conversations. Sometimes it gets a bit overheated, but I try not to take it personally.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the rarest buttons in your collection?

Aisthorpe: One of the rarest is linked to the 1968 Chicago DNC and the arrest of the “Chicago Seven”—Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, John Froines, and Lee Weiner—who were charged by the federal government with conspiracy and inciting to riot. It’s called the “Chicago Imprisonment of Peace” button and depicts a peace dove behind barbed wire with “Chicago” printed over the dove.

Another standout, albeit not as old, would be my “What’s So Intelligent About the CIA?” button. That came from the end of 1986 when 50-year-old Abbie Hoffman and 19-year-old Amy Carter, the daughter of President Jimmy Carter, were arrested and charged with trespassing and disorderly conduct for protesting CIA recruitment at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. In early April 1987, their case came to trial in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Left, a button protesting the treatment of the Chicago Seven in 1968. Right, a 1986 pinback against CIA recruitment on college campuses.

Before the trial, Abbie Hoffman contacted Larry Fox and asked him to make this button for use during the lead-up to the trial and the trial itself. After Fox made them, Abbie distributed them to supporters.

The prosecution was confident that the six-person jury would not be sympathetic to the actions of these so-called radicals. Attorney Leonard Weinglass, who had defended Hoffman on the Chicago Seven trial in the 1960s, successfully argued that because the CIA was involved in criminal activity in many places around the world, that should prevent them from recruiting on campus. He asserted a “necessity defense” in saying that the protests were equivalent to trespassing in a burning building to save a life. Hoffman and Carter were acquitted of all charges.

Collectors Weekly: Do you think political pins are still relevant today?

Aisthorpe was told to remove this button, featuring a quote from Eldridge Cleaver, at his polling station.

Aisthorpe: In today’s world, they’re most relevant to collectors and at conventions, since we can no longer wear political paraphernalia near voting booths, where these buttons were once most visible. I tried wearing one that was just a quote from Eldridge Cleaver of the Black Panthers, “If you’re not part of the solution, you are part of the problem,” but that wasn’t allowed either. One person told me they didn’t even want him to wear a George Washington button because it could be viewed as “party-affiliated.”

I rarely wear my buttons out in public, but the times I have, several people commented on them—mainly compliments like “Cool button!”—or they’d point them out to their friends and laugh. When I choose to wear one, it’s often related to a current event, like the day the announcement was made that our Special Forces killed Bin Laden, I wore a “Rest in Pieces” button with his image behind a bulls-eye that was put out months before.

Political pins seem to have made a comeback on campuses, though they were never really gone. One of the rarer buttons worn at colleges was the “Hoover Lives” pinback made in 1972, the year of J. Edgar Hoover’s death and refers to F.B.I. recruiters still being on campuses. But I think there has been a resurgence, and a lot of the old messages seem to be more relevant than ever—if we don’t learn from history, we’re doomed to repeat it.

Some specific slogans have recently returned, primarily on “Resist” or “Resistance” buttons. One of those that I posted on CollectorsWeekly is the 1972 pin reading “Resist Now More Than Ever,” made by John Swinglish, who was one of the Camden 28, a group of Catholic anti-Vietnam activists. The post received several comments from users asking to revive this button.

A 1972 pinback whose slogan has become popular again.

Bob Alexander of Guardfrog Designs, who makes very limited-edition buttons, has also helped modernize pinbacks. Many Guardfrog buttons have an old-style look incorporating vintage advertising imagery, and Bob uses different types of Mylar or celluloid covers for more of a matte finish that looks different from most buttons. Bob gave a bit of fresh air to our stagnant hobby with his double-bubble pins, meaning one smaller button mounted on a larger button. It’s a very unique look. I was on a Guardfrog kick for a while buying several hundred of his designs.

In general, prices on many pinback buttons have done nothing but increase. The most I’ve seen a single button sell for was $31,500.00. That was a 1920 James Cox and F.D.R. jugate button. However, that same “Cox Roosevelt” button has a $100,000.00 open offer for any new examples that turn up (other than the seven already known in private collections). Some buttons have dropped in value, so as always with collecting, buy or barter for pins you like—not for their investment value. I still seem to go for the anti-establishment buttons; it’s deeply ingrained. But I haven’t met many buttons I didn’t like.

Two buttons designed by Guardfrog’s Bob Alexander in 2008 with antique-looking imagery. (Click to enlarge.)

(All photos courtesy John Aisthorpe unless otherwise indicated.)

Vicious Vintage Campaign Buttons

Vicious Vintage Campaign Buttons

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets Vicious Vintage Campaign Buttons

Vicious Vintage Campaign Buttons The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights Political PinbacksWant a quick tour of the U.S. political landscape of the past 100 or so yea…

Political PinbacksWant a quick tour of the U.S. political landscape of the past 100 or so yea… Politics and Public ServiceHistory is often told through the grand detritus of the political sphere—th…

Politics and Public ServiceHistory is often told through the grand detritus of the political sphere—th… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great information and story John and Hunter! Perfect timing for this article. Yes, that was me with the Geo Washington button :-) immortalized in print!! well, in the cloud, you know what I mean.

I have enjoyed all your postings John. Keep the posts coming. Great interview, full of history thumbs up to you and Hunter.

Surprised to see anything be Guardfrog here. Bob Alexander has produced fake, reproduction and fantasy buttons to dupe new collectors. These fakes are bad for the hobby and Collectos Weekly should be ashamed of promoting him.

Nice article. Just wanted to point out that the great Bertrand Russell was a great intellectual and the prominent figure of CND, but he never designed the Peace symbol. Gerald Holtom, a student at the Royal College of Arts in London, did it.

Thanks for that catch Michael! We’ve since updated the text.

I have the original pin.

MAKE

AMERICA

BETTER

BEGINS

WITH

ME

well just remember to watch out for the fakes that Kleenex made in the 60s & 70s

Lots of collectors like to destroy these

So beware of the Kleenex Fakes!

A great article on buttons, button collectors, and the history of pinback buttons. Nice of you to mention us.

I recently wore a dozen of my anti-Vietnam war buttons on a trip to Vietnam. Well received in Hanoi, but took them off toward the south where guides families penalized for support of US. Went on the first march in DC at age 15 (without permission) and have dozens of civil rights and anti war buttons that I wore in those years.