Once upon a time, in a galaxy suspiciously similar to our own, people decided what movies to see on Friday nights and at Saturday matinees by thumbing the pages of their daily newspapers until their fingers were dark with ink. Eventually, after much rustling and folding, they’d arrive at the paper’s “entertainment” section, where single-color, text-and-graphics advertisements for the latest flickers from Hollywood promised thrills, chills, action, laughs, and romance. There were no multimillion-dollar marketing campaigns, no targeted ads on social media guided by insidious psychometric profiles. Primitive as it sounds, black ink on white newsprint was the primary means of enticing people to spend two bits on a movie ticket.

“At one point my wife said to me, ‘Exactly how many of these are you going to buy?”

Even more primitive were the physical advertising assets themselves, which were initially made out of etched zinc plates that were subsequently mounted onto blocks of wood. One of the handful of companies that manufactured these “print blocks” or “cuts,” as they were variously known, was KB Typesetting, whose location in Omaha, Nebraska, made it a convenient hub from which to ship print blocks to newspapers around the country. Typically, these blocks were tossed in the trash when a newspaper had finished with them, but enough of these artifacts of movie-advertising history survived to create a small market for print blocks among die-hard movie-memorabilia collectors.

Top: A selection of the 50,000 or so print blocks owned by DJ Ginsberg and Marilyn Wagner. Above: When purchased in 1999, their blocks filled more than 400 boxes weighing several tons. Both images via “The Collection.”

That quaint little world of finite supply and demand was blown to smithereens—as thoroughly as the planet Alderaan—in November 1998, when DJ Ginsberg and Marilyn Wagner of Omaha were invited into the back room of a local store called Franx Antiques and Art. That’s where they first encountered a cache of 400-plus cardboard boxes filled with more than 50,000 assorted-sized print blocks, plus another 8,000 or so printing plates, all featuring advertisements for movies produced from 1932 to the early 1980s. It was literally tons of stuff, and it had been sitting in that back room, undisturbed, for roughly two decades, when Franx purchased it for several thousand dollars from its Omaha neighbor KB Typesetting.

Naturally, Ginsberg and Wagner had to have it all. So, they scraped together the money to purchase the collection from Franx and find a place to store it, and proceeded to load all those boxes, albeit a few at a time, into Ginsberg’s car.

“My poor Corsica got beat to death,” Ginsberg tells me when we spoke over the phone recently. But the Corsica was the least of Ginsberg and Wagner’s worries: Like the proverbial dog chasing the milk truck, the bigger question confronting the two friends was what to do with their prize now that they had caught it.

DJ Ginsberg, Omaha, Nebraska, 2017. Image via “The Collection.”

Fortunately, one night after their weighty acquisition, Ginsberg and Wagner were watching “Antiques Roadshow” on television, and in that episode, movie-poster expert Rudy Franchi happened to be doing an appraisal.

“They called me in 1999,” Franchi explains, “and they said, ‘Maybe you can help us.’ I knew right away what they had because I’d seen cuts over the years, but never more than three or four at a time. They were regarded as curiosities from the Stone Age of printing. But all of a sudden, here were thousands of them, from ‘The Mummy‘ through ‘Star Wars.’ We talked for quite a while.”

Franchi was due to be in Des Moines, Iowa, soon for a “Roadshow” taping, so he offered to swing by Omaha, which is not too far away. “Meanwhile,” Franchi says, “I was talking to the people at ‘Roadshow’ about the collection, and they said, ‘Well, if you’re going there, why don’t you bring back a few blocks, and we’ll do a special segment on them.’ So, I went to Omaha and saw the collection, which was amazing, grabbed some cuts, and headed back to Des Moines.” In the end, Ginsberg and Wagner joined Franchi for the segment. “Then they hired me to do a formal appraisal of the whole collection. At that time, 1999, I estimated its value at $1.8 million. That’s when things got out of hand. They went on ‘Oprah,’ they were all over television, in newspapers, everything.”

Marilyn Wagner checks a print plate against its inventory entry. Image via “The Collection.”

Eventually, life quieted down for Ginsberg and Wagner, but in 2017, a short documentary by filmmaker Adam Roffman called “The Collection” refocused the spotlight on their cache, and earlier this year, Franchi was hired to update his appraisal, which now stands at between $18 and $20 million. Not surprisingly, that’s the range currently being trumpeted by Guernsey’s in advance of its upcoming auction of Ginsberg and Wagner’s horde, which is being sold as a single collection.

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God, I have to see that collection!'”

What happens to the collection next is anyone’s guess, but before we speculate on its future, let’s take a moment to look back at how several tons of print blocks found their way into the back room of Franx Antiques and Art in the first place. To do that, we need to meet a man named Loren Kelley, whose half-century of unheralded doggedness and diligence is one of those classic American stories that Hollywood loves.

Our hero—played, perhaps, by a young Henry Fonda—is a son of Omaha, and if you have not figured it out by now, he would one day become the “K” in KB Typesetting (the “B” was his partner, Joseph Bondi). He’s also the guy who sold all those tons of print blocks and plates to Franx some time in the early 1980s.

Color residue on the surface of many print blocks is usually not ink. It’s a sealer that’s intended to protect the metal from oxidizing. Image via “The Collection.”

For our purposes, Kelley’s story begins in the 1920s when he enlisted in the Navy. Right away, that should tell you something about the aspirations of the landlocked Nebraskan. But alas, Kelley did not “see the world” during his stint in the Navy. In fact, it’s believed he was stationed in California near Los Angeles for his entire tour.

To supplement his Navy pay and give purpose to what must have been a grindingly dull peacetime tour, Kelley spent his off-duty hours working for printing companies, which meant he did a lot of projects for Hollywood movie studios. In those days, as the silent-film era was becoming the age of the talkies, studios hired printers to produce everything from lobby cards to movie posters for their films. These materials did a good job of catching the eyes of patrons already in movie theaters, but what about less-captive audiences? To reach this larger pool of potential customers, the studios needed to get into people’s living rooms and join them for breakfast at their kitchen tables. Studios quickly learned that they could do both by advertising their upcoming motion pictures in newspapers.

Cleaning the surface of an old print block is easily accomplished with vinegar and a wire brush. Image via “The Collection.”

Creating the zinc plates that made these intrusions possible became one of Kelley’s chief non-naval skills. In fact, according to DJ Ginsberg, Kelley was very good at the art of photo etching zinc (that metal was eventually replaced by magnesium) and mounting these reversed images of movie advertisements onto blocks of wood, which were cut into numerous, standard, newspaper-column sizes. When these print blocks were sent to newspapers, they would be placed amid rows and columns of type and other blocks, given a coat of ink, and run through a press, resulting in a positive image on the page. In this way, print blocks helped people answer the question of what movie to see on Friday night or at the Saturday matinee.

Upon returning to Omaha in around 1932, Kelley set up shop as KB Typesetting, leveraging the relationships he had established with numerous Hollywood studios. The studios already liked Kelley for the quality of his work, but now that he was in Omaha, KB Typesetting became a preferred place to manufacture these all-important Hollywood advertising assets—from Omaha, it was as easy to send print blocks to Chicago as it was to send them to New Orleans or New York. As luck would have it, KB would become one of only a handful of companies that made print blocks, and it may have been the biggest. Thus, in his own quiet way, Loren Kelley became one of the most influential movie marketers of the first half of the 20th century.

In the top image, one can see the small nails that have been pounded through the zinc plate and into the block. Because the heads of the nails are not raised as high above the plate as its inked surfaces, they do not appear on the final ad (bottom image). Images via “The Collection.”

But what was really weird, amazing, and even inexplicable about Kelley was his early decision to save at least one example of every block and plate he produced.

Think about that for a minute: In Hollywood, actors, directors, and producers are only as good as their last hit, yet Kelley treated all of the ads he produced for the more than 12,000 movies that crossed his work table with equal regard, from run-of-the-mill B-movies to “The Wizard of Oz,” “Casablanca,” and “Gone With the Wind.” Did he do it out of pride of workmanship? Was he secretly a devoted movie fan? The truth is, we’ll never know, because other than the foregoing, little is known about Loren Kelley. Still, it’s a safe bet that when he retired in the early 1980s and decided to unload his life’s work for a relatively paltry sum at Franx, it did not cross his mind that one day the physical products of his career would be valued at $20 million.

If Kelley’s story is a bit of a mystery, Ginsberg and Wagner’s is less so, thanks to Oprah, all that publicity the pair received in the early 2000s, and Roffman’s 11-minute documentary. Screened in 2017 at film festivals from Austin to Anchorage, and available for free viewing anytime on Vimeo, “The Collection” has introduced an entirely new audience to Ginsberg and Wagner’s story, as well as to the role print blocks once played in promoting movies.

By 1964, when “A Hard Day’s Night” was released, print plates were mostly glued to their blocks, so this print block has no visible nails. Images via “The Collection.”

While some documentarians view themselves as journalists, Roffman is hardly a dispassionate observer when it comes to print blocks—his personal horde of print blocks is up to about 350 pieces, all of which he has collected in the last four years.

“I was shooting a short documentary in Connecticut,” Roffman tells me, referring to the day in 2014 when he purchased his first print block. “One of the people I interviewed owned an antiques store in Waterbury. It looked like a hoarder’s house, filled wall to wall with these mounds of perhaps 150 objects apiece, pile after pile. After we finished the interview, while my cameraman was breaking down the lights, I went over to one of the piles and gave it a little push at the top to see what treasures might lie underneath. That’s when I found my first print block. It was for a Claudette Colbert movie from 1934 called ‘Imitation of Life.’ It was in pristine condition, all shiny and beautiful. I knew it was a movie advertisement, but I didn’t understand how it had been used, why everything on it was backwards, or any of that.”

Prints blocks manufactured by KB Typesetting, such as this one for “Fiddler on the Roof,” have numbers stamped into the sides so that they were easily identifiable by compositors working in busy newspaper press rooms. Image via “The Collection.”

A self-described “massive movie buff,” Roffman let his curiosity lead him on a journey to learn all he could about print blocks, including where to find more. “I started hunting for them in antiques stores, at thrift shops, and at antiques fairs,” he says, “but I wasn’t finding very many. A few people online had small collections, so I started buying from them. Eventually my wife bought me two movie blocks for Christmas, and included with those blocks was a Xerox of a 1999 newspaper article about DJ and Marilyn from the ‘Omaha World Herald.’ When I read it, I was like, ‘Oh, my God, I have to see that collection!’ And if I was going to see it, I knew I should make a movie about it.”

The fact that Roffman was a collector helped him gain Ginsberg and Wagner’s trust. Coincidentally, the pair was also getting ready to put their collection on the market, so the timing was perfect for a film.

“I flew out there with my cinematographer, Nathaniel Hansen, and we really hit it off with DJ and Marilyn,” Roffman says. “Our first half day there was spent doing nothing but looking through boxes, just trying to find things we wanted to film. We had a fun time making the movie, and I think DJ and Marilyn were happy with it, but both Nathaniel and I wish we had budgeted three or four more days to be out there. We didn’t have nearly enough time to look through the whole collection.”

Print plates, such as this example for “King Kong,” were used to make paper print sheets so that movie-theater managers could choose the size ad they wanted to run. Newspapers would then order the print block in that size from KB Typesetting. Images via Guernsey’s.

While Roffman’s film focuses almost exclusively on the print blocks, Ginsberg and Wagner’s collection also includes thousands of print plates, which were used to print one-page sample sheets showing all the possible ad configurations for a given film. “Take a movie like ‘Gone With the Wind,’” Roffman says. “The print plate for a movie like that would be an 8-by-10-inch metal sheet that would have seven or eight ad sizes on it, in different shapes and designs, too. A paper print from that plate would be sent to the movie theaters so the managers could decide what they wanted to run on week one, week two, and so on. The movie-theater manager would then take that print to their local newspaper and say, ‘I want this ad on this date, and that ad on that date,’ which was the information the newspaper needed before they ordered print blocks from KB Typesetting—newspapers only ordered the sizes they needed.”

The plates stayed in Omaha, where they were saved for posterity by Kelley. The blocks were sent to the newspapers, where they were used and then, in most cases, tossed in a furnace, which is what makes Kelley’s decision to keep an extra archival set of every block he made at KB such a gift to movie historians and collectors.

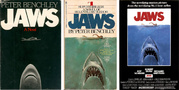

The potential for producing and selling authorized, limited-edition restrikes on archival paper for films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With the Wind” are one of the main reasons with Ginberg and Wagner’s collection is valued so highly. Images via Guernsey’s.

It’s also what makes the collection of some 60,000 objects coming up for auction worth the $18 to $20 million that Franchi says they’re worth and that Guernsey’s hopes they’ll bring. It’s not only what they are, but also their potential. Indeed, the future value of the print blocks as a group is an important part of Franchi’s appraisal calculation.

The price of the blocks themselves depends on the film being advertised and the condition of the block. Sometimes print blocks are in great shape, like that first one Roffman bought in 2014, but others are not, or at least they don’t look it. That means a sharp-eyed collector can get a good deal if they know what they are looking at. “I bought a ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ once,” Roffman says. “The person selling it didn’t seem to realize that all of the dried ink on it was not permanent. It looked really rough and beat-up when I received it in the mail, but after I soaked it in vinegar for a minute and wiped it off, it was as good as new. It probably would have sold for 20 times the price I paid if the seller had known how to clean it.”

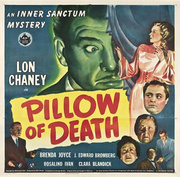

Some of the blocks in the collection are iconic films such as “Casablanca” and “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Images via Guernsey’s.

Roffman says that the most he’s ever spent on a print block is $75, but Ginsberg and Wagner have seen them sell for much, much more. But even so, where does Franchi get his $18 to $20 million appraisal?

For Franchi, the answer lies in what new prints, or restrikes, made from all those 50,000 print blocks could be worth, and that number, he believes, is closely related to the market for movie posters.

“In 1999,” Franchi says, “many vintage movie posters were selling for around $200, rarely into the thousands. But the week that I did my second appraisal, Heritage Auctions sold a ‘Dracula’ for half a million dollars. These days, it’s not uncommon for posters advertising major films to sell for $100,00 to $400,000.”

The owner of this print block could start selling prints of this “Star Wars” ad tomorrow. Image via “The Collection.”

Obviously, that’s a lot of money, but restrikes are not movie posters. And, Franchi says, “Appraisals can’t predict the future. In general, when you appraise something, you appraise what’s in front of you, not its potential. But here, the real value was that one could print thousands of limited-edition prints.” In other words, the potential value of what Ginsberg and Wagner had collected, a cache that is almost certainly one-of-a-kind, could not be ignored.

Franchi says the case law on this potential value is clear. “Movie-advertising materials are basically exempt from copyright protection,” he says, “because they never copyrighted this stuff.” Studios copyrighted their movies, he says, but they didn’t copyright the advertising materials because they wanted newspapers and other outlets to spread the word far and wide. To put it in contemporary terms, studios wanted the advance buzz about their movies to go viral.

A selection of print plates made by KB Typesetting. Image via Guernsey’s.

Franchi learned firsthand about this strange corner of copyright law when he was hired as an expert witness in the trial of an entrepreneur who was reprinting old movie posters. “It was a massive lawsuit,” Franchi says. “This fellow was selling his reprints in Walmart and Target by the tens of thousands. So Warner Bros., which had the rights to ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ sued him.”

During depositions prior to the trial, Warner Bros. got schooled on the limits of its ownership of “The Wizard of Oz.” Among other things, they learned that movie posters were never copyrighted because, as Franchi puts it, “The last thing the studios wanted to do was copyright a poster because that would inhibit its distribution.” No copyright, no copyright protection. Warner Bros. dropped the case before it even went to trial.

All the genres are represented in the KB Typesetting collection, including Westerns. Images via Guernsey’s.

Print blocks, Franchi believes, are similarly immune from the constraints of copyright law. “Newspapers wouldn’t run stills if they had to get copyright permission every time,” he says, “so the cuts were not copyrighted. If you were just reprinting them on paper, then you were not changing their use. That was the key.”

And that’s why Ginsberg and Wagner’s collection of print blocks, 75 percent of which Ginsberg says are in good enough condition to be used for restrikes, could easily be worth the $20 million Franchi says it is, if not a whole lot more.

Filmmaker Adam Roffman made the poster for his movie out of restrikes of print blocks in his personal collection. Image via “The Collection.”

For his part, Roffman has made a few restrikes of his own with the print blocks that he’s collected. In fact, the poster for “The Collection” is composed of more than 30 restrikes, featuring ads for everything from Elvis Presley in “Girl Happy” to Natalie Wood in “West Side Story.”

As for collecting, Roffman’s slowed down. “At one point my wife said to me, ‘Exactly how many of these are you going to buy?’” Still, Roffman does keep an eye out for obscure titles. “I saw a print block for sale of ‘The Ghost and Mr. Chicken’ with Don Knotts,” he says. “The seller wanted something like $300 for it. I offered $60 because I’m a fan of that movie, but they said, ‘No thanks, somebody will buy it.’ And somebody did.”

(Update, 9/4/18: DJ Ginsberg and Marilyn Wagner have decided not to sell their entire collection as a group after all. Instead, they will be producing restrikes in both limited and open editions and offering those for sale. First up will be a limited edition restrike taken from the “Star Wars” print block, which actually features the signature of artists Tim and Greg Hildebrandt in the plate. For more information, visit their website. You can also watch Adam Roffman’s short documentary, “The Collection,” at Vimeo. Special thanks to Tim Sawyer.)

Hunting Down the Most Collectible Movie Posters, from 1930s Horror to 1960s Sci-Fi

Hunting Down the Most Collectible Movie Posters, from 1930s Horror to 1960s Sci-Fi

Mondo: The Monster of Modern Movie Posters

Mondo: The Monster of Modern Movie Posters Hunting Down the Most Collectible Movie Posters, from 1930s Horror to 1960s Sci-Fi

Hunting Down the Most Collectible Movie Posters, from 1930s Horror to 1960s Sci-Fi Real Hollywood Thriller: Who Stole Jaws?

Real Hollywood Thriller: Who Stole Jaws? Printing EquipmentMetal and wood type, the cabinets designed to hold these blocky letters and…

Printing EquipmentMetal and wood type, the cabinets designed to hold these blocky letters and… Movie MemorabiliaWhether it’s fantasizing about the life of a movie star or wishing you live…

Movie MemorabiliaWhether it’s fantasizing about the life of a movie star or wishing you live… AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci…

AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

This article needs more research. First, very, very few large, rare, original, color movie posters are selling for more than $10,000, much less more than $100,000. By definition, none of these cuts meet any of these criteria. Second, the better analogy is to reproduction photographs. What a rare original photo of say Ansel Adams sells for is in no way related to what a reproduction will sell for even from the original negative. And by the way, what do original cuts from newspapers sell for? Very little. 98 percent of these cuts as reproductions will not sell and aren’t worth very much- and if someone wanted to put hundreds, much less thousands of the blocks on the market it would soon be flooded with them as the market of collectors for negative zinc blocks is very thin. Consider how few people have the ability and means to produce in any kind of commercial way genuine prints from these blocks- to monetize them. Further, the lack of a copyright, as suggested, if accurate, also works against the creation of reproductions by whomever buys these. I don’t think the writer has done sufficient research on copyright- the famous Mickey Mouse image copyright case may also apply, for example, to other Disney cuts, reducing any value they have in their reproduction. One avenue that might be monitizable would be the use and availability of these images through a Getty, Thinkstock or other services, but again, 98 percent of these images have little or no commercial value even in this kind of venue. I do not think any credible auction house would put a value at more than a fraction of the figures bandied about in this article, and none would guarantee it, and that’s a guarantee…

Someone didn’t do their homework and it wasn’t the writer!

1999 – King Kong Poster sold for $244,500

2007 – The Black Cat Poster sold for $286,800

2009 – Dracula Poster sold for $310,700

1997 – The Mummy Poster sold for $435,500

2017 – Casablanca Poster sold for $478,000

And that just to list a very, very, few!

If the buyer were to make prints from the original vintage plates, they would be considered re-strikes, certainly not reproductions.

A well known movie poster appraiser put the value on this collection based on the fact that it’s the only collection of it’s kind in existence and the fact that the images can be printed on several different sub-straits.

Personally, I’ve seen these “cuts” go as high as $800-$900 dollars each when sold separately.

You’re comparing apples to oranges since you don’t know the difference between a reproduction vs a re-strike.

As for the copyright, the appraiser of this collection was called as an expert witness on several cases involving copyright issues and probably knows more about the laws governing the re-strikes and this collection of original movie material then most attorneys.

After checking out the website on this collection and doing a little homework about the appraiser, I’m surprised the appraisal wasn’t much higher. I also learned that even IMDb doesn’t have some of these images. i.e. Lost Art!

I wish they would sell the blocks individually. I won’t be bidding on the entire collection; but, I’d pay a few hundred bucks, each, for the few blocks & plates that I would love to have.

I have fifty years in dealing in this sort of thing.

The first commentator is correct.

The second commentator is correct as well.

This collection is unique.

As such, all bets are off.

The auction could go either way.

Guernsey’s wouldn’t be involved if they harbored great doubts about the salability of the collection.

They are masterful promoters.

I have a 1944 Coca Cola war printing plate , bronze, w/two soldiers, one Canadian, one American, drinking Coca-Cola.

Why don’t you do an update on this article. His collection went up for auction and didn’t draw a bid.

The real value for this collection seems to be way way below what was touted in this article, I’m guessing five figures.

Cheers

If it was sealed bid, I’m confused as to why you “assumed” there were no bids or maybe you have some insider information which we would all love to hear Frank.

Based on the update posted by Mr. Marks, it appears they want to go a different route and re-strike the plates. I went to their website and found that Greg Hildebrandt (the original artist for the Star Wars posters) quoted about the Star Wars plates they own.

Obviously they have talked with Greg and the plates they have of Star Wars deserve to be struck and sold since they are original and made before the movie was released.

Seems to me collectors will jump on these prints since they are one-of-a-kind and no others exists.

After working in printing for over 30 years now, and having had my hands on some very rare and valuable items myself, I can assure you that these print blocks will only become more valuable as printing technology changes.

why don’t you flip the images so they aren’t backwards

I have yearly week to week scrapbooks with the newspaper movie advertisements from Friday’s papers.

Would these be of any interest to someone?

Getting ready to part with them.

Thanks for any help you can give.