Long before the cynical Millennials, the snarky Brat Pack, and bad-boy greasers of the 1950s, teenagers were finding their own voices—and using them to scream at their elders. Most historians pin the origins of teen culture to the 1950s, when adults first noticed that adolescents were dictating trends in fashion, music, film, and more. But director Matt Wolf’s latest film, called simply “Teenage,” challenges the notion that this turbulent, in-between life stage is a modern development.

“Regardless of their circumstances, adults either aimed to protect or control them.”

Based on Jon Savage’s book of the same title, “Teenage” is an exploration of youth culture before mass media had a firm grasp on the concept of adolescence, from the beginning of the 20th century up to World War II. Using archival footage and firsthand accounts, “Teenage” examines the various movements that paved the way for today’s teen angst, helping audiences empathize with the excitement, fear, and indignation felt by restless youth more than 100 years ago.

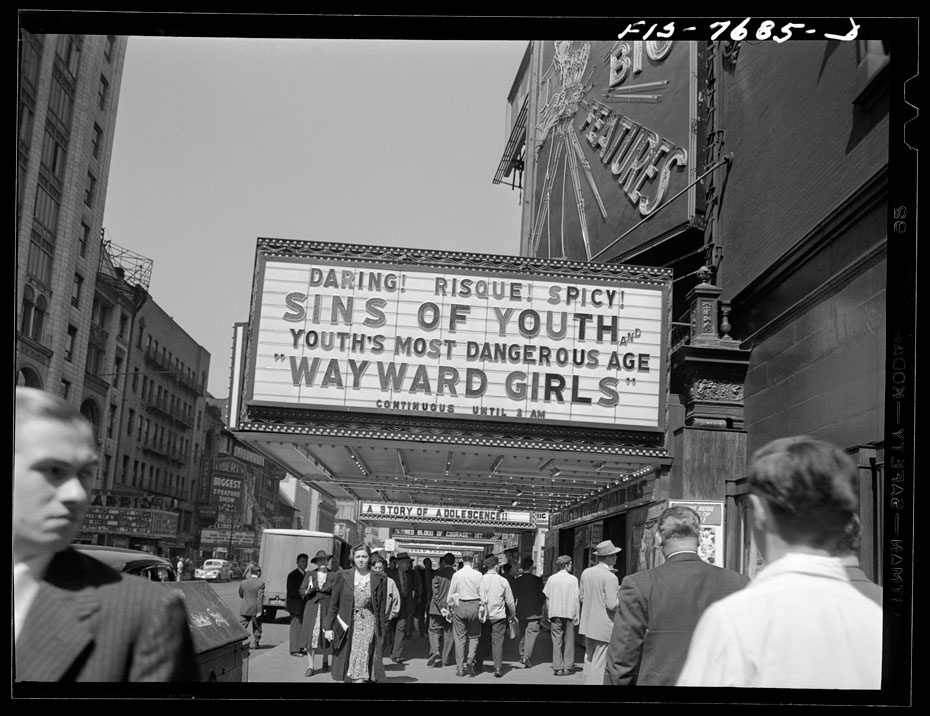

“The old had sent us to die, and we hated them,” recounts one young man early in the film, in reference to the carnage of World War I. “Teenage” goes on to show how such emotional turmoil has repeatedly ignited youthful rebellion: Whether by embracing shockingly risqué behavior, like the Bright Young Things in Great Britain, or arch-conservative political beliefs, like the National Socialist (Nazi) Party in Germany, the film reminds us that teenagers have consistently challenged the world of their parents, trying to build the perfect future for themselves.

We recently spoke with Wolf about the teenage protagonists of his film, and how their struggles are connected to today’s youth.

Top: Wolf re-created certain sequences using complicated analog methods, like this scene representing the early 1940s. Above: A collage of youthful images used in the film.

Collectors Weekly: Why does the film begin in 1904 as opposed to a decade earlier, when the book starts?

Matt Wolf: From the get-go, Jon Savage and I created a rule for the film—we were only going to tell stories that had a strong basis in actual archival footage. I actually didn’t think I’d be able to go as far back as 1904, because I didn’t think I would find film footage of adolescents from that period, but we did. Some of the earliest footage we used shows teenage girls in a reformatory from the turn of the century, having a pillow fight. That was taken by Thomas Edison, so it’s very early footage.

We also felt like the Industrial Revolution and the advent of child labor was a good way to bracket the story, since once you went to work, you were no longer considered a kid. When they started to make child labor illegal, this second stage of life emerged, and it needed a name. It was called adolescence. That was a natural starting point for the film.

“Teenage” begins with the dawn of child-labor laws and their impact on the lives of adolescents, as seen in this archival photo of child coal miners, circa 1910.

Collectors Weekly: When was the term “teenage” first used?

Wolf: We identified the publication of the “Teenage Bill of Rights” in 1945 in the New York Times as the first important use of this term that defined this new type of people as a social class entitled to specific rights and responsibilities. That marked a turning point in the use of the word, but it was percolating before then. The accepted history of the “teenager” begins with things like “Rebel Without a Cause” [1955] and the rockers in the 1950s, and it continued through the hippies and beatniks and punks, all these types that we’re familiar with.

“Young people face the highest unemployment, and feel they’re suffering the consequences of the previous generation’s greed.”

As I started getting into the material, reviewing Jon’s book and his research, I recognized how political it was. I was initially intrigued by the book because Jon’s punk perspective really colored his depiction of early 20th-century history. I love forgotten biographies, rather than more famous stories, and that’s the premise of his book: To uncover this prehistory of the teenager, and to tell all these hidden histories. In his book, unlike the film, Jon reexamines familiar myths like Peter Pan, and also iconic teenagers like Anne Frank, but he treats the subjects from a new point of view, questioning things that people take for granted and assume they know about.

Collectors Weekly: How did you settle on the four central characters?

Wolf: Jon’s book is sprinkled with all these biographies. Sometimes they’re in-depth and sometimes they’re just a paragraph. I’m a traditional biographer, but I knew the film would have this panoramic narrative to it, and that it would be important to telescope in and out for some emotional release from the larger span of history.

We chose characters that we felt represented a diverse range of race, class, gender, and nationality, but also different character types. We wanted flamboyant, exciting people like Brenda Dean Paul, the Lindsay Lohan-type, or Tommy Scheel, the proto-punk. But we also wanted “squares” and right-wing people. The experience of Melita Maschmann was fascinating to me because so much of the Hitler Youth narrative has been told through these images of the masses. I thought it was important to try to empathize with the reasons someone that young would join this organization and what her emotional and political background was. I found her diary to be so vivid.

Left, a re-created shot of Melita Maschmann, the Hitler Youth. Right, a scene with two “Bright Young Things,” an affluent party subculture in 1920s London.

It was very difficult to find narratives from people of color from the time period because they were omitted from the “official” histories. There was this sociological study from 1940 called “Negro Youth at the Crossways,” which included a lengthy interview with Warren Wall, and that felt like such a gold mine to me. Here was the direct voice of a young African American boy at a time when he would have been completely excluded from all other forms of documentation. It felt important to bring him to life, and also to show how his style of rebellion was being a square and trying to advance in society, despite the color of his skin.

Some of the voiceover commentary was scripted to further the narrative, but the foundation was quotes from actual teenage diaries and written testimonies. I would also say that about 80 percent of the film is archival footage. We worked with over a hundred archives, historical societies, and individuals for this film—researchers in New York and Washington, D.C., but also in the U.K. and Germany.

Warren Wall, one of the young people interviewed for “Negro Youth at the Crossways” in 1940, rebelled by joining the all-white Boy Scouts.

Collectors Weekly: Why did you decide to re-create footage, and what techniques did you use?

Wolf: I wanted to go deeper into these character narratives, but there’s no original footage of these obscure adolescent figures—Brenda, Melita, Tommie, and Warren—so I used re-creations to stand in for footage that doesn’t exist. The only time we used new footage that we shot ourselves was to bring those four central characters to life. It was pretty labor-intensive: We aimed to create the effects of archival footage without using digital tools, because that usually looks fake and cheesy. We were really inspired by Woody Allen’s movie “Zelig,” where he re-created the look of 1920s newsreels.

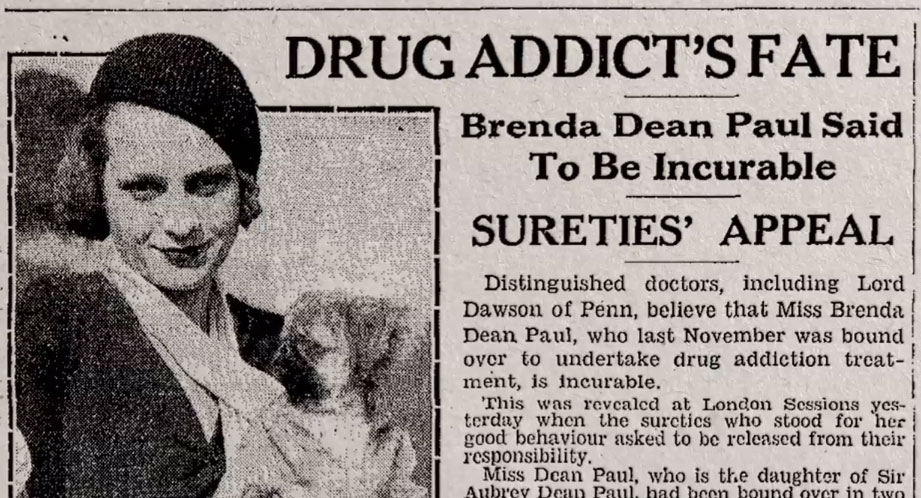

Left, a still of Brenda Dean Paul from a re-created segment of “Teenage.” Right, an original photograph of the notorious socialite, circa 1920s.

I’ve done re-creations before, but they were more contemporary, so it was really a challenge to figure out how to do the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s thing. My last film was about a musician named Arthur Russell, and he was also an absent subject. There was very little documentation of him, so I shot a lot of material on old VHS cameras. I used Arthur’s actual clothes and had an actor wear them and shot material with a VHS camera and used Super 8 film.

For “Teenage,” we sourced old 16mm lenses, stripped the coating off those lenses, and used them on hand-cranked Bolex cameras. We shot 16mm film in this crude way, and then we’d make what’s called bleach-bypass prints. It’s almost like a VHS dub, but using a chemical process for 16mm film that softens and degrades the image. Then we scratched those prints, or ran them on the floor. We put coffee-grain stains on them, and then transferred them again.

We kept degrading the footage through these analog techniques and transferring it over and over again, and that’s what makes it look authentically old. In the ’20s, there was some color film, and we did a lot of research into that because I wanted color to come into the film earlier; I didn’t want the film to be black and white until halfway through. We did a lot of historical research in terms of our production process to be as accurate as possible.

Collectors Weekly: What links the more conservative characters and the more progressive ones, beyond simply their youth?

Wolf: I think what connects all of these characters is the pressure of adult society to control them or to regiment them, and regardless of their circumstances, adults either aimed to protect or control them. They all internalized it in different ways, and rebelled against it. That feels like the central tension of the film—this model of regimentation and then this kind of rebellion, in which young people try to create their own world, their own culture.

Coverage of Brenda Dean Paul’s notorious addictions was commonplace in the tabloids during the 1920s.

Particularly with the London riots in 2011, many images from the film feel like a parallel time and a place. People have remarked on the repetitiveness of certain themes in the film, and I think that’s essential—the cyclical nature of these events, and how certain social patterns repeat themselves and continue to today. Within this cycle, a lot of change happens, and teenagers are active agents of that change. It’s out of rebellion that things are moving forward.

I think so much of the political agitation of young people now is about the poor decision making of their parents, especially as a result of the economic collapse in recent years. Young people face the highest unemployment, and feel they’re suffering the consequences of the previous generation’s greed. Whenever war is present, young people are also suffering the consequences of adults, with the militarism and violence hurting them disproportionately.

Collectors Weekly: What is the importance of music in “Teenage”?

Wolf: Most archival footage is silent, which many people don’t realize, so it needed extensive sound design and soundtrack music. I like having a lot of music in my films. I think of my films, but this film in particular, as having a quality that’s similar to a record, where you can watch it and have a satisfying emotional experience as the imagery washes over you. But you can also listen more closely, and the voiceover functions like lyrics to deepen the experience. It has more meaning.

“That sense of possibility and active imagination about the future is much more vital when you’re young.”

I also wanted to collaborate with Bradford Cox, [of the bands Deerhunter and Atlas Sound] who’s one of my favorite musicians. One of the goals was to contemporize this historical material, and Bradford’s aesthetic blurs the past and the present in a natural way. To me, putting vintage period-appropriate music feels very stodgy and grandparent-y. But the second you put contemporary music with this material, it’s like, “Oh, I am that person—I could totally be there.”

But the music was really enhanced by sound design as well. My sound designer did tons of work to very literally bring certain sounds to life, but also to blur the boundary between real sound effects and more impressionistic things. I think the overall effect is quite dreamy, and that was the tone I was going for.

Collectors Weekly: How was music central to the youth movements featured in the film?

Wolf: I think swing music was the key subculture of the early 20th century. It has an obvious political dimension, in that it was African American culture being absorbed by interracial youth and creating an integrated social space. Eventually, swing became a part of this mass culture that was celebrated globally. The film demonstrates the political dimension of this music when it was smuggled into Nazi Germany, and how that became this unexpected form of rebellion and resistance. To me, swing and jitterbugging represent an important intersection between pop and politics.

I also think swing was the first major musical subculture, and most subcultures that we can identify afterwards were driven by music and pop stars. I think the footage shows that swing was really different and exciting, and the dancing was wild. It was very punk.

Collectors Weekly: Did you feel a kinship with the youth in your film?

Wolf: I was a very political teenager, a gay separatist teenager who thought I was changing the world in the Bay Area, and maybe in some way I was. It was the post-Matthew Shepard, Ellen DeGeneres era. Making this film, it caught me by surprise how much I remembered those feelings and the sense of urgency or immediacy I had in terms of changing the world. You lose track of those feelings as an adult living in a big city.

I guess I’m too experienced to feel like my individual actions can change the world, but as a young person I wasn’t. I really did feel like everything I did mattered, even if just to me. I really identified with that in the material for the film, and tried to put myself in the shoes of people from different experiences, like a Hitler Youth, even though I’m a Jew. It’s interesting to identify with these extreme characters. The film is more about exceptional young people, not boring conformist teenagers, but that’s what I was like as a teenager and so I could identify with it.

“Teenage” reminds viewers that rebellion came in many forms, as seen in this archival photo of girls and guns, circa 1920.

Collectors Weekly: Did making this film change the way you treat teenagers in your real life?

Wolf: Completely. I work with teenagers, like the girl who plays Melita. We found her in Tompkins Square Park. She was having her own little Romeo-and-Juliet drama in the East Village—her mom wasn’t allowing her to see her boyfriend, so they’re sneaking out, and she was crying and screaming on the phone. She’s a rebellious, wild, beautiful teenage girl, and I helped her to translate those feelings into the context of being a Hitler Youth. It was fascinating, and she helped me understand what Melita’s feelings were because she was literally going through this drama in the van on the way back from filming. She was inspiring to me, like a muse in a way.

Adults know they have to actively lift themselves out of the present to create some sort of better future. Their aspirations are more tangible and reality-based. Teenagers don’t have that freedom—they can’t make their own decisions in the most basic sense. Whether they’re truly oppressed politically or whether they just feel emotionally oppressed by the circumstances of living at home, until they’re free, they’re not going to feel like they have the ability to shape their own lives. That sense of possibility and active imagination about the future is much more vital when you’re young.

(All images courtesy Matt Wolf.)

Found Photos: When Rock Lost Its Innocence

Found Photos: When Rock Lost Its Innocence

Nostalgia is Magic: Tavi Gevinson Remixes Teen Culture

Nostalgia is Magic: Tavi Gevinson Remixes Teen Culture Found Photos: When Rock Lost Its Innocence

Found Photos: When Rock Lost Its Innocence 'The Great Gatsby' Still Gets Flappers Wrong

'The Great Gatsby' Still Gets Flappers Wrong PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P…

PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Very well written Hunter and Love the History of how the term Teenager came about!!!

It’s so true, our parents never understand us when we are teenagers. A great interview and wouldn’t have known about the film otherwise.

I appreciate you sharing this article.Thanks Again. Really Cool. cedddgddggbe

Helpful info. Fortunate me I found your website by chance, and I’m shocked why this twist of fate did not took place earlier! I bookmarked it.

Sounds like an interesting movie and book. Interesting too that Wolf thinks teenagers can’t make decisions…tell that to those who leave home early to live their own lives and make it in the big wide world, such as my late stepbrother who left home at fifteen due to my mother’s Nazi-like tendencies with us! Now that is a decision.

I ‘ve seen arguments that jangly youth cultures emerged from communications innovations. Cheaper printing; widespread personal vehicles from canoes to bicycles to autos; telephony to radio, and recorded to broadcast music; and now ubiquitous digital and wireless connectivity. Each new medium (often hacked) allows new protests against reactionary elders. How will youth movements evolve from here?