In this interview, Steve Cabella talks about collecting the work of designers Charles and Ray Eames, and about the mid century modern movement.

As a teenager, I collected everything from vintage bicycles to Coca-Cola to Victorian stuff. Once I realized some of this stuff contained concepts of art and design, I started looking for vintage objects that also represented art or design movements that could hold my interest. I ran across Art Nouveau and then Art Deco and then Arts and Crafts and then streamline modern. Visually it all led up to mid century.

Let me just say, I put on the first mid-century show in America back in the late 1970s. Back then people made fun of mid-century stuff. For years I was actually called Mr. ‘50s. That was a derogatory term in those days when everybody just looked up to Art Deco. Then they rediscovered certain movements, but it was always pre Art Deco stuff like Arts and Crafts or different offshoots of that. Nobody could see the beauty of mid century then, really, except the people who were still living with it.

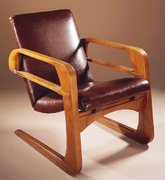

Eventually I started to run into people who appreciated mid-century design. I ran into my first Eames chair one day in a garage sale, and it happened to be basically one of the first models ever made. It was a 1946 model, but had all these pre-production features. When you looked at the new Eames chair, it looked so different than the old one, but had a lot of visual hints about how and why it was constructed. What got to me about the Eames stuff was the fact that it was incredibly honest furniture, an honest product. The Eames stuff was timeless. It was still good design 50 years later.

That Eames chair had a lot of oddities about it, which caused me to see who these people were. It was one of the first pieces of furniture I ever turned over and it said designed by Charles Eames. You don’t find those words on objects too often, “designed by.” The whole concept of industrial design really didn’t come about until the 1930s, anyway. It wasn’t even a career for people, so the consumer didn’t know what designed by meant, really. But by the time Charles was doing it in the ‘40s, it was an accepted term. He put it on everything the office designed. I had no trouble finding out who Charles Eames was because if you looked around you could see him in daily use.

In the 1970s Eames was everywhere, and the goal then became to find the oldest Eames things. That’s how my collecting started. I realized you could find these old Eames things in junk stores or in the homes of the original owners. At the time I did a lot of estate work. I handled the estates of artists, architects, designers, engineers, craftspeople, photographers, writers.

I’m a collector that’s never had a dime to collect with. As a teenager and being in art school, I never had any money to throw at this stuff, but I went after it. When I went to art school, everybody I wanted to learn from was retired, and so I had to go find the old teachers in order to learn what it is I wanted to learn.

In collecting, I had to go after the original owners, and it ended up to the point where I would handle their estates or make little films about them. They had such interesting stories to tell – what I call lost moments. When I built my Eames website, one of the reasons was to share these lost moments. I think that’s one of my responsibilities as a collector.

I’m also a serious collector who shares things. I’ve loaned thousands of things to exhibitions over the last so many years. I work hard at preservation and sharing the information I’ve turned up. If you just don’t get people on film or anything you’ve already devalued their collections because you’ve lost the stories that potentially a new owner could get, that would help them understand what they’re collecting.

Collectors Weekly: What kinds of shows were you doing?

Cabella: As a teenager, I was doing some of the first mid century modern shows in America. Then I started doing exhibitions where I’d share stuff with people, sort of educational exhibitions. The first one was at the College of Marine Art Gallery in 1978 or ’79. I did exhibitions for the public, sometimes in conjunction with galleries or museums. I did the first Eames show in Japan a few years ago. It was basically my own collection, and it was a big hit.

When I was a teenager, I used to hang around with older folks in the North (San Francisco) Bay and South Bay who’d get together once a month and do these amazing balls or dance gatherings. Everything had to be authentic, not because you were forced to, but because you could. You were allowed to share that love and that joy, and it just helped people understand everything that everybody was collecting. Collectors don’t really do that anymore.

When I’d lecture about Eames furniture, one of the first things I’d do is ask the crowd, “How many of you own a piece of Eames furniture?” Practically every hand would go up. Then I’d go, “How many of you have more than one piece of Eames furniture?” and most of the hands would stay up. But when I’d say “All right… that makes you collectors, but how many of you actually love your furniture?” pretty much all the hands would go down. Collectors, you sometimes have to break their arm to get them to say how much they love the stuff that they’re collecting.

Collecting is just a weird love for an object. Eames stuff is that way partially because the Eameses touched so many areas of design, and love was part of their formula. They made furniture, toys, art, films. It just goes on and on. You can collect Eames stuff in so many different areas.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell us a little bit about Ray and Charles Eames?

Cabella: Sometimes they’re erroneously referred to as two brothers or brother and sister. They were actually a husband-and-wife team. I’ve made some documentary films about them. I’m presently making 100 one-minute films about details of their life and careers. I just finished a documentary on Ray and Charles Eames in Hollywood and how much they contributed to Hollywood filmmaking, unbeknownst to lots of people.

“Charles died knowing he was adored, one of the design gods. Ray was still living a little bit in the background.”

Charles was an architect/designer, and Ray was a native Californian who met Charles at Cranbrook, the art school where she was studying to be a painter. They met there and married shortly after, during the war, and came to Los Angeles where they knew people in the film world. Charles had some notice as an up-and-coming student designer. He was a young designer who hadn’t established himself with any firms but set up his own business, something most people didn’t do. You usually worked for a client.

Charles just set up his own firm along with Ray, and the pair of them made a really top design team. They should get equal credit. For years just Charles got the credit because that’s how the business was set up. He thought the consumer would be confused if things said by Charles or by Ray. It was always just Charles Eames, but that covered everybody who worked for him, in the same way the designer Raymond Lowy had designed the Studebaker Hawks and other things. People thought he did everything. No one man could have done everything that has Charles’ name on it; it was a team effort.

They worked from the ‘40s all the way up until the early ‘70s, constantly making furniture. They’ve made over 125 films like Powers of Ten. And half a dozen toys. They influenced everything from fashion to filmmaking to furniture design, and did exhibitions around the world, design installations for other countries, world fairs. You would call them Renaissance people, really. They influenced so many people. They had a bazillion fans.

They didn’t have many failures, and if you bought something with Eames’ name on it, you bought a quality product guaranteed. They weren’t selling a trend. They had nothing to do with trends. The trends came after them with lots of copycat designs. Lots of mid-century collectors collect things influenced by the Eameses, which is just fine. I also do exhibitions of things influenced by the work of Ray and Charles Eames. Ray and Charles were like teachers for many students.

Collectors Weekly: Do you collect just the furniture?

Cabella: No. I have probably the largest private collection of the work of Ray and Charles. My favorite phrase by Charles Eames is the thing called the connection… that everything’s related. It’s all in the details. So my Eames collection is full of details. Not just their pieces of furniture. I try and get the prototype and the pre-production models to show people how subtly the idea changed when it went into production. Or I’ll get the toy and all the original advertising for it, and I’ll seek out original photographs of the toy being developed.

I collect lost moments, beyond just collecting things, I collect stories or objects that illustrate things, that tell a story. In some of my films, I study an object, so people can look at their objects in a more developed way, something that normally would take a collector years to develop. What I’m most interested in is telling the story.

I have artwork that the Eameses did in the ‘30s before they were known as designers. Several paintings done in the ‘30s. It shows how amazing they were 10 years before people thought of them as designers. People think they were just plopped on the planet in 1944. They never think of them as young students or young artists or painters or sculptors or whatever. I’ve interviewed a lot of people who worked for the Eameses, and they just tell amazing stories. It’s just shocking that people can be that creative, and part of it is because they were focused. They knew the value of being creative.

Collectors Weekly: What was so unique about their designs?

Cabella: At the time, most “designers” were just trying to design furniture that would sell. The Eameses wanted to design furniture that answered people’s questions or problems or issues or needs, primarily their needs. In the process, they came up with furniture that looked unique because they were using unique materials and manufacturing processes, mostly in an effort to save the consumer money and provide them with greater comfort. It required them to be experimental. They were working without constraints, just looking for the best answer.

Not many people were doing this. Their only design hero, the one man Charles ever said he was a fan of was a guy named Dr. Peter Schlumbohm who designed the Chemex coffeemaker, that hourglass-shaped clear thing with a wooden collar. His theory on design was the fact he wasn’t a designer. He was just a guy who made things and it looked the way they looked because that’s how they had to look in order to act the way they were supposed to function. He was just being incredibly honest and hoping there were honest consumers out there who would appreciate what he did.

The Eameses had the same philosophy. They weren’t giving in to anybody. That’s what made their stuff unique. Everybody else accepted constraints, whether it was the manufacturer saying, “you’ve got to use this material,” “it’s got to be this color,” or “it’s going to cost this much.” The Eameses were pioneers.

They would work on a chair and make 50 of them. A hundred of their friends would sit on it and check it out. They would really look into it and try and put as much into that product as they could whereas most people were trying to put as little as possible into it. They also loved to do things as art or sculpture or creative objects.

The Eameses had a huge impact from 1946 to 1976, they were everywhere. If you were talking design or architecture or you are walking in some modern-looking building, Eames was there. I used to do these street exhibitions where I would take maybe a dozen Eames chairs to a street corner and group them or line them up and just watch what people say. And it was surprising because everybody had something to say.

Part of Eames is in the American vernacular visually, whether you know the name or not, you went to school, you sat on it. You went to cafeterias, you went to businesses, you went to halls, auditoriums, the parks they designed. It was just everywhere. So much so that some studios, you had to bend their arms to put an Eames chair in a scene During that period, Eames was ubiquitous like Elvis.

Collectors Weekly: What kinds of materials were they using in their designs?

Cabella: They tried practically everything, but settled on some materials they knew would be a lasting resource for them. They were fans of aluminum, steel, wood and fiberglass, and plainly painted Masonite, because those all had honesty in materials. Not like some Baroque embedded upholstery where you’d try to make it look like a fake piece of natural something when it wasn’t.

I have pieces that used plumbing pipe as legs because they needed a straight piece and hey, plumbing pipe works. Why should we have some fancy steel leg manufactured by somebody when all we really need is a straight piece of pipe? If the material answered the question or problem, they would use it. And they always looked for a better or more beautiful way to make it.

People pay for beauty. When the plywood Eames chairs came out in the 1940s, they were $13, $16, not that expensive. That was the cost of maybe three tires for your car at the time, but you were going to keep that chair for 50 years. And they were going to make it so it didn’t go out of style for you or break in 50 years. They weren’t always successful. Some things broke because they were experimental.

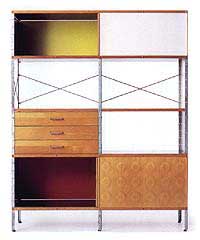

They made every piece of furniture imaginable. Tables, coffee tables, kids’ tables, rolling tea carts. Big, beautiful, architectural style cabinets. In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, they did some prefab dormitory housing for students that would’ve been incredible, but society changed and students liked their own junk in their dormitories and so that went by the wayside. They’re being revised now because they were such beautiful things.

They made indoor furniture, outdoor furniture, corporate furniture, furniture for kids. The furniture was pretty comfortable for the elderly. They kept that in mind. And it was furniture designed for use around the world.

Collectors Weekly: So they were around for this whole Mid-century Modern movement, right?.

Cabella: Well, yes, at the revival of the movement. When it first started out, it wasn’t called mid century. When I started doing this, the term we had was postwar, my first exhibition was called Postwar Design in America. This was stuff done from the day the war stopped, World War II, to a decade later, the Korean War. That’s how people related to it, but exhibitors and store owners and some writers didn’t like the word war being associated with design.

Most revivals start with a retrospective that somebody or some museum puts on that gives really deep credit to somebody. They say to the public, look, we’re celebrating this because they did all this stuff. And then the stores and collectors and pickers and writers pick up on it. They all called it mid century because it made them more comfortable, basically.

It’s funny because mid century is truly 1935 to 1965, but when people write about mid century now, they stop at 1946. They don’t go back to what is truly mid century. Charles died first and Ray died 10 years to the day that he died. She woke up in her hospital bed surrounded by her family and she said “I know what day today is,” and then died. Isn’t that incredible? The Eames thing is not all a pretty picture because nobody’s life is a pretty picture. He was known as a womanizer, and she had health problems.

But back to the mid century appreciation, Charles died knowing he was adored and still teaching new generations as they came along. By that time he was being looked at as one of the design gods. And Ray was still living a little bit in the background. She got credit for some stuff but not nearly enough. That’s now changing. When Charles died, there weren’t any exhibitions or collector fairs when his stuff came up for sale. The stores were still all selling Art Deco stuff.

But before Ray passed away, she had been to many retrospective fairs and antique shows where they featured her work. The one time I got to meet her was when I did one of the first shows down in L.A., and she strolled through. And at that time, not everybody had an Eames thing in their booth.

Not everybody knew what Eames was. Not everybody knew Ray. She was barely even five feet tall, wore a little Victorian dress and just sauntered through the show.

She stopped at my booth because I had so many Eames things, and she talked to me not like a dealer or collector but just said, “you have a lot of Eames things.” And she said, “I’m looking for a plywood tabletop for one of my tables. It was a rare table. Do you have one?” And I did. She just saw it like a consumer, that I might have one in stock or whatever. She didn’t know that people highly collected her stuff or were just starting to. I sent her the tabletop for her table, and she sent me a little note saying thanks.

She also got back on the lecture circuit. I went to several of her lectures, and they actually brought chairs, which amazed people. She was there to teach young students, not help collectors necessarily. She was very much the teacher and a sharer. I collect stories from people that have met Ray. Once a woman came up to me after one of my lectures and told me she’d sat next to Ray Eames on a train from California to New York in 1955.

She goes, “I ordered lunch, and this little lady next to me whipped out a picnic basket and set out a little tray of stuff, food I’ve never seen, on plates that were just all mixed up and crazy, looking like set of dishes.” She talked to her and Ray said that she was a designer and an artist. But then the woman totally forgot her until she ran into her again ten years later on a plane to New York.

According to this woman, Ray whipped out a little cardboard box with food and set her own little dishes up on a little tray in front of her. And the lady asked, “What’s this with the dishes? Why are the dishes all different?” And Ray said, “Well, why shouldn’t they be?” They had a little discussion about aesthetics and having everything different and appreciating different eras, and how being an eclectic collector can really change your life. And the lady told me, “I went home and went to the thrift store and bought completely different dishes, and that changed my life.” It opened up a creative moment, let her appreciate visuals in life.

So I collect stories like that. I don’t think Charles and Ray ever knew they were going to be big with collectors until the end.

Collectors Weekly: When did the Mid-century Modern design movement start?

Cabella: Well, in the ‘60s, when Victorian things became collectible, people had been collecting true antiques at the time, pre-revolutionary war furniture and French craft. That became an expensive market. So people started collecting Art Nouveau stuff because it was cheaper than all this snooty colonial crap. And they could find it because society was starting to throw it out in the garbage, re-development tore down the old neighborhoods and the stuff just landed in the street. Young collectors or pickers would start picking it up and taking it to secondhand stores. That’s how most collecting starts. And once it’s become a collecting trend, it goes through revival every 10 years or so.

So mid-century stuff really started to be collected about 1980. Before that, everybody was collecting either industrial design or high-end Art Deco or streamline modern. But all that stuff started to become worth a lot of money. Desk lamps were $5,000. So the young collectors started to ask, well, what can I collect? And mid-century design was the next natural step from streamline modern. They started collecting postwar.

You have to remember that most people were still hanging on to this stuff, and it was mixed in to a lot of kitschy stuff that had no design quality to it. They weren’t done using it, the original owners who bought it in the late ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s. So you had to look through a lot of kitschy stuff, which I called dog meat, to find something that was really true mid-century or postwar design.

About 1980, the stuff started to hit the marketplace through auction houses and stores. If you’re going to call it mid-century design, then you be honest that some of it was done in the late ‘30s, and ‘40s, not just the ‘50s and ‘60s. Lots of people, they just wanted to know about the trendy part of it, the ‘50s stuff. But once the truly good ‘50s started going to auction houses and serious collectors, they started looking at the ‘60s stuff.

I’m still a firm believer that if you’re going to say mid-century then it’s 1935 to ’65. Get used to it, people! Stop trying to rewrite it just for the sake of your collection. Some people say, “I collect mid-century,” but all they have is stuff from the ‘60s. There’s very little that actually gave birth in the ‘50s or the ‘60s. It was all part of a continued conversation of creativity.

In collecting, you can collect either the high-end, the medium, or the kitschy end of things. I won’t say low end, just kitschy. That covers everything from crafts, ceramics, wood ware, jewelry, textiles even. Some people collect the furnishings or the dishes or the art, because they want to complete the environment. Other people collect the books, original brochures and things like that because they want the information from the original source. It’s almost like getting the ticket to time travel when your library has enough documentation to where your mind goes oh, yes, I’m surrounded by everything old.

Collectors Weekly: Who were some of the other notable furniture designers from the Mid-century Modern movement?

Cabella: There’s a lot of them. Some contributed a few incredible objects; some, like the Eames, contributed to an entire lifestyle. If you’re going to collect European designers, be aware that the majority of their great work is still in their country of origin. We were only given their products. We weren’t really given their lifestyle. In America, you did have certain people who cared enough to try and contribute to all facets of your lifestyle, and most of these people turned out to be icons like the Eameses. But there are lots of forgotten people who were great contributors but are only well known regionally. Now that there’s been a revival, some of these regional people are becoming nationally known.

So in terms of designers you could say were up there with the Eameses, you had people they worked with like George Nelson. You have Irving Harper. You have Russell Wright, of course, and Henry Dreyfuss. One of my favorites is Raymond Lowy. I drive a Lowy designed car. Some of the local people starting to become bigger names include Van Keppel Greene and Claude Conover, who was a big designer for something called the Pacifica movement, basically the mid-century design movement basically on the West Coast. And then there were other regional designers who are just as important, the little lamp makers, the dish makers, the jewelry designers.

Collectors Weekly: Any books you can recommend for people interested in collecting Eames or mid-century stuff?

Cabella: I’m a big fan of original resource material from the period. Look at those catalogs and magazines first. Magazines like Arts and Architecture, Architectural Forum, Design Monthly or Interiors Magazine, those will tell you the true story. Books tend to leave out a lot of the details. By all means, go to your library or talk to a retired designer and look through the older stuff, it gives you better continuity and detail. New books are trying to write the history a few hundred pages. So buy that vintage magazine for $10 and read it three or four times. Read the ads. See what people are saying, and how everything fits in.

(All images in this article courtesy Steve Cabella)

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

For the Love of Danish Modern Furniture

For the Love of Danish Modern Furniture Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA Eames ChairsCharles and Ray Eames, who pioneered modern chair design in the 1940s and '…

Eames ChairsCharles and Ray Eames, who pioneered modern chair design in the 1940s and '… Mid-Century Modern FurnitureMid-Century furniture describes tables, chairs, dressers, and desks marked …

Mid-Century Modern FurnitureMid-Century furniture describes tables, chairs, dressers, and desks marked … FurnitureNot all that long ago, when someone mentioned the word "antiques," the firs…

FurnitureNot all that long ago, when someone mentioned the word "antiques," the firs… Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly …

Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Thanks for the article. The best interview that I have read in a long time. I stumbled upon it by accident looking for some information on a mid-century bent wood chair that I spotted today for $30.

I knew Steve during his Art Deco phase, he Opened My Eyes! What a talented guy, he really knows his stuff. Thanks for the great article, kate

Steven is wonderful. I still have many paintings, lighting and furniture that I purchased or was given by Steven. I miss living in my home town in Marin mainly due to the fact that I can not visit Stevens store!

He is a wealth of knowledge and if he trusts you will give it freely.

Love ya Steven!!!

Looking forward to seeing the films.

Hello!

I am trying to find where I can get an appraisal on a Herman Miller/Eames designed bedroom suite. I live in the Cleveland, OH area, and the furniture includes two dressers, a night stand and twin headboards all of solid cherrywood with metal legs and white ceramic knobs. The furniture, which is in mint condition, was Eames designed and is from the 1950’s. Any assistance you may have would be great!

Thanks much….

Best regards,

Debbie Gipson

Hi Steve, I called you a few years back, and we had a nice conversation about Eames and Nelson. I still have most of my Eames and Nelson furniture, but at this writing, I am 1 month away from 93. I graduated from Univ, of Mich in architecture and then studied Ind. Design at Art Center in Cal. all on the G.I Bill. and worked for Harley Earl Assoc. when I bought most all of my good stuff 1953-7, My 4 sons are doing their own thing. Need advice how to sell it with honor. B.