When you think of 1950s Atomic Age design, a handful of images probably pop into your mind: The Ball Clock. The Marshmallow Sofa. The Sunburst Clock. What you probably don’t realize is that the designer of these Mid-Century Modern icons spent decades living in obscurity, filling his upstate New York farmhouse with 300-some whimsical handmade paper sculptures of animals, Pre-Columbian and Southeast Asian figures, Cubist abstractions, and African masks.

But in a few weeks, Irving Harper and all of his delightful creations will come into the light, thanks to a new Skira Rizzoli book, Irving Harper Works in Paper, which hits stores February 12, 2013. This full-color tour of Harper’s personal sculpture collection is the result of an effort by Michael Maharam—who first visited Harper’s home in 2001—to preserve these unique works of art.

Top: A cat attacks a bird in Irving Harper’s paperboard sculpture. Photo by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.” Above: Harper’s 1949 Sunburst Clock is still credited to George Nelson on the site of Swiss furniture company, Vitra, which sells them now. Image via Vitra.com.

“Whenever the Marshmallow Sofa is referred to as a ‘George Nelson design,’ it sort of gets to me.”

Harper, who is now 96 years old, worked for the George Nelson Associates design firm between 1947 and 1964, the height of Mid-Century Modern innovation, developing a wide array of products.

While there, Harper created the Marshmallow Sofa for Herman Miller furniture, as well as the company’s logo, and the Ball and Sunburst clocks for Howard Miller. These products are still made and sold today—and still largely credited to George Nelson.

As the CEO of Maharam, a textile design company, Michael Maharam sought out Harper in early 2001, hoping to reissue a couple of the Herman Miller textile patterns he designed—Pavement and China Shop—for Maharam’s Textiles of the 20th Century line. Traveling to Harper’s wooded home in Rye, Westchester County, he discovered a wonderland of paper art, and a quintessential Mid-Century Modern designer feeling slightly defeated by the lack of credit he received for his inventions.

Harper reads the paper in his living room, surrounded by his own artworks. Photo by Leslie Williamson, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“He was this very vital, vivid guy, and he was eager to help out in validating the re-edition of the textiles, which, of course, was a rare experience for us,” Maharam says. “For the most part, we’d been dealing with deceased designers, and so we relied upon our intuition for a deeper view of their work. But in this case, we had somebody who had actually designed textiles 50 years earlier, which is really luxurious.”

Touched, Maharam purchased an iMac for his elderly colleague and showed Harper how to Google himself. Harper, who had never owned on a computer, was floored to see his name come up thousands of times. Maharam also tipped off his friend Paul Makovsky, the editorial director of Metropolis Magazine, about this unsung, living creative force of the 1950s. Makovsky also headed up to Harper’s home in Rye and made his “Being Irving Harper” piece the Metropolis cover story in June 2001.

Maharam worked with Irving Harper to reissue two of his 1950 Herman Miller textile prints in 2001, China Shop (left) and Pavement (right), for Maharam’s Textiles of the 20th Century line.

Thanks to the Internet, it wasn’t long before the underdog found new champions. Artist and illustrator Matte Stephens was so inspired by the Metropolis article, he decided he had to see Harper’s artwork for himself, and finally made it to Rye in 2007, a trip documented on Design Sponge. In 2010, Guy Trebay was similarly moved to cover Harper’s creations for The New York Times’ T. Magazine.

When Maharam checked in on Harper in the wake of his wife’s death in 2009, he noticed that all these beautiful, one-of-a-kind paper sculptures were starting to deteriorate and fade from the sun. So he asked the designer how he’d feel if Maharam and his colleagues restored and photographed his sculpture for a new book.

The bird and 25-inch human figures in Harper’s window sill were made from construction paper. Photo by Leslie Williamson, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“He was very happy about it,” Maharam says. “We sent my wife’s excellent manicurist up there with the photographers for a week, and she did all the restoration work because she has good hands for that sort of thing. And the photographers documented everything. I have to say it was really touching to visit with Irving, share the advance copy of book, and be able to give him some homage to his work. It was a very sweet thing.”

In the 2001 Metropolis article, Harper explained that in the 1950s, the designers creating the bold new look of the future had almost a rock-star status. “They were considered geniuses, individuals responsible for transforming the look of American product,” Harper told Makovsky. “So there always had to be one name associated with the work.

Three views of an owl sculpture, made of painted craft paper and doll eyes, which was the last piece Harper completed before he ran out of display room. Photos by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“Well, that’s fine,” he continued. “I’m grateful to George for what he did for me. While he was alive I made no demands whatsoever. But now that he’s gone, whenever the Marshmallow Sofa is referred to as a ‘George Nelson design,’ it sort of gets to me.”

“His design work has become the shorthand for the 1950s, which was not an easy thing to do.”

Harper wasn’t the only fertile Mid-Century Modern mind working under George Nelson, producing pioneering furniture pieces for Herman Miller. Nelson often hired Mid-Century Modern superstars like Charles and Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi, and Alexander Girard. Others labored in semi-obscurity: John Pile made the Pretzel Chair, Charles Pollock the Swag Leg Armchair, George Mulhauser the Coconut Chair. Ronald Beckman and John Svezia collaborated on the Sling Chair, while Ernest Farmer designed the Case Goods modular storage. As chief designer, Harper oversaw most of these projects, too.

Nelson himself was never a designer. When Julie Lasky, the deputy editor of the New York Times’ Home section, visited Harper, he divulged to her, “I never saw George sit down and design anything.” An architect and brilliant writer, Nelson made a name for himself in the design world because he had an articulate design philosophy, an eye for talent, and the sort of outsize personality to get the media attention and show-stopping gigs a world-class creative firm needed. Harper, on the other hand, was more the quiet sort who prefered to sit at his draft table and make things.

The abstractions on this wall were made from balsa wood, Japanese tissue paper, matchsticks, construction paper, and paperboard. The masks are made of construction paper, paperboard, glass doll eyes, plastic packaging, ping-pong balls, twigs, and corrugated cardboard. Photo by Leslie Williamson, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“That is the way of design firms everywhere,” says Lasky, who was recruited by Maharam to write the introduction to Works in Paper. “They’re not very different from science labs. All those Nobel Laureates in biology and chemistry have many people who are running those experiments. And the university-based scientist puts his or her name on every paper that comes out of his or her lab even though that person is not necessarily sitting at the bench. The scientist is directing the lab, but not doing the actual labor.”

Even today, Nelson is celebrated as a founder of American Modernism, who “tore the numbers off clocks,” as he was at a Yale School of Architecture exhibition that closed this month. But for an introverted creative type who didn’t have the impresario personality, working for George Nelson Associates was a pretty sweet deal. “For a good 16 years or so, Irving Harper helped build George Nelson’s reputation, and George Nelson gave a place for him to tinker, have fun, and make money,” Lasky says.

Harper’s construction-paper dancer. Photos by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

In fact, Harper’s interior design career was something of a happy accident. He grew up in New York City, where he studied liberal arts at Brooklyn College after high school. At night, he took classes in architecture at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Graduating in the middle of the Depression, he found that architecture jobs were scarce. But in 1938, Harper got hired by the Modernist architecture firm of Morris B. Sanders to work on the interiors of the Arkansas Pavilion for the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

That’s when he discovered his designer calling, at age 22. Harper quickly moved on to a job with industrial designer Gilbert Rohde, who had helped define the Art Deco Streamline Moderne movement in America and also worked as the design director for Herman Miller furniture from 1932 until his death in 1944. For Rohde, Harper created more 1939 World’s Fair interiors, for the Plexiglas exhibit, the Anthracite exhibit, and the Home Furnishings Focal. In 1940, Harper married lawyer Belle Seligman, who shared his left-wing politics.

Harper’s piano room is decked with trophies, busts, and other artworks he created. Photo by Leslie Williamson, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

During World War II, Harper served in both the Army Corps of Engineers and the Navy, and when he returned, he conceptualized department store interiors for industrial designer Raymond Loewy, who eventually devised the 1953 Studebaker. Bored with his work for Loewy, Harper was thrilled to take a job with George Nelson in 1947, who had assumed Rohde’s position at Herman Miller and was also founding his own design firm, George Nelson Associates.

Right away, Harper was presented with a challenge: Inventing a new logo for Herman Miller furniture, with no clue as to what the upcoming George Nelson-influenced line would look like. Harper made a large wood-grain patterned M using a swooping French curve, a brand image the company still employs 66 years later.

The first time Irving Harper’s wood-grain M logo for Herman Miller appeared was in this 1947 ad. From “Irving Harper Works in Paper,” courtesy of the Herman Miller Archive.

But perhaps the object that sparked Harper’s wild imagination most was the clock. For Howard Miller Clocks, Harper came up with dozens of geometric, numberless wall clocks, resembling exploding stars and suns, spindles, and streamlined abstractions, as well as desk clocks shaped like bubbles, moons, and wooden diamonds mounted on pedestals. The first of these was the Ball Clock, a wall clock featuring 12 metal spokes capped with colored wooden balls that look like those in an Atomic Model Kit.

Ever the showman, Nelson had a knack for creating myths about his firm’s designs. And one myth is so persistent that Harper can do nothing to rebuke it. In fact, the story still lives on at Design Within Reach, which sells a “1948 Nelson Ball Clock” reproduced by the Swiss furniture company Vitra.

A persistent myth is that the 1948 Ball Clock emerged out of a drunken dinner party with Harper, George Nelson, Isamu Noguchi, and R. Buckminster Fuller. Harper says in reality he made it at work, like the others. Image via Vitra.com.

“Nelson was at a dinner party with Isamu Noguchi, Irving Harper and Bucky Fuller,” reads the DWR product page. “As the story goes, they were all sketching and ‘we’d had a little bit too much to drink,’ said Nelson. In the morning, they saw a drawing of the Ball Clock on a roll of drafting paper. ‘I don’t know to this day who cooked it up,’ said Nelson. ‘I know it wasn’t me. It might have been Irving, but he didn’t think so. [We] both guessed that Isamu had probably done it because [he] has a genius for doing two stupid things and making something extraordinary out of the combination. It could have been an additive thing, but we never knew.’”

Harper, however, says that he does, in fact, remember creating the Ball Clock, sober at work, on an ordinary workday. But the tale is much more fun than the boring truth. However, Lasky says, “to me, the clock does not look at all like Noguchi.”

Over the years, Harper made all sorts of Modernist furniture, graphics, interiors, and housewares for Herman Miller under Nelson’s name, from china sets, plastic silverware cases, and lamps to slide projectors, record players, and typewriters. But besides the Herman Miller logo and the Howard Miller wall clocks, the other Harper design that’s endured is the Marshmallow Sofa—which, initially, was a complete failure.

A new edition of the Marshmallow Sofa is currently for sale at the Herman Miller web site. Initially, it was too expensive to be produced in large numbers. Image via HermanMiller.com.

Harper built the model over a weekend on a lark in the mid-1950s, after a plastics-company salesman presented Nelson with round, flat vinyl cushions, made of a plastic that supposedly formed its own skin and wouldn’t need to be upholstered. However, the technology required that the cushions could be no larger than 12 inches. Harper took 18 of these vinyl pads, and arranged them into the Marshmallow Sofa design.

“It’s evident that, at 96, Irving Harper is still a young person at heart.”

Ultimately, the self-skinning injection-molded plastic technology—which was meant to save the company the tremendous cost of hand-upholstery—failed, and the Marshmallow Sofa was produced with traditional upholstery. Because it had 18 small cushions, it was even more expensive to make than a regular couch, and initially, Herman Miller only produced 200.

However, this strange piece of furniture so captured the spirit of Mid-Century Modern, it developed a cult following. It’s been revived and is offered by Herman Miller today. A new Marshmallow Sofa sells for nearly $5,000, while a vintage one can go for as much as $15,000.

Harper’s sculptures go from floor to ceiling in this particular room of his home. Photo by Leslie Williamson, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

Thanks to new Herman Miller editorial director Sam Grawe, former Dwell editor-in-chief, the company’s Why Design series produced a video last fall on Harper’s sculpture called “Paper Is a Versatile Medium” in which Harper is credited with both the Marshmallow Sofa and the Ball Clock. The Herman Miller product page now credits both Nelson and Harper for the couch, while the shopping page does not.

After their daughter, Elizabeth, was born in 1953, Irving Harper and his wife, Belle, moved from New York City to their spacious, sunlight-filled farmhouse in Rye, New York, but they didn’t have much décor of their own, so it was largely empty for 10 years until Harper began his fidgety hobby of tinkering with scrap paper and glue.

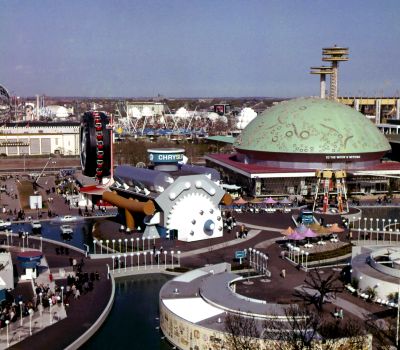

The Chrysler Pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, designed by Irving Harper’s team at George Nelson Associates. Image from TheTruthAboutCars.com

By 1964, the stakes were high. And Harper, as Nelson’s chief designer, had a bad case of the nerves. He and his team were planning the Chrysler Pavilion for the upcoming New York World’s Fair, which involved building an enormous pool containing islands linked by footbridges. Each island highlighted an aspect of car production, including an enormous walk-in engine with pistons that shot sparks as they jogged up and down.

But deadlines and high expectations had him on edge. So he did what any twitchy engineer would do: He built something. One night, he took apart a bamboo window shade and glued the twig-like pieces with household cement into a peculiar mask. He made more sculptures later that year, when he struck out on his own, joining up with veteran Nelson designer Philip George to create their own firm, Harper+George. The pair developed interiors for companies such as Braniff International Airways and Hallmark Cards, until Harper retired in 1983.

Harper’s first sculpture, a mask made of matchstick-sized pieces from window blinds, sits in a clear case on his windowsill. Photo by Leslie Williamson, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

The whole time Harper continued to tinker with his playful sculptures, made from paper, Elmer’s glue, and whatever he had lying around the house, like toothpicks, matchsticks, pine cones, pasta, and clock parts. When his daughter got old enough to abandon her dolls, those became material for the Surrealist stage of his art. In 2005, Harper ran out of room to display and store his artworks, which by then numbered around 300, so he stopped making them. Then, in 2009, Belle passed away after 69 years of marriage.

“Individually, the sculptures can be appreciated for their charming translations of art historical masterpieces, their structural ingenuity, or their deft expressions of color,” Lasky writes in Irving Harper Works in Paper. “They are arresting down to the hinge, piercing, or loop. Collectively, they form a sumptuous catalogue of one man’s perambulations along the boulevards of twentieth-century aesthetics. Arranged in simple, bright rooms among primitive artworks and contemporary furniture—much of which are Harper’s own prototypes—they testify to the playfulness and omnivorous appetites of the era’s great modernist designers … [and] reflect lives joyfully lived.”

Harper took the head from one of his daughter’s discarded dolls and added toothpicks and pine cones. Photo by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

Maharam agrees that Harper’s artwork reveals his sprightly mind. “Clearly, he has the best fertile imagination you would hope a person who maintains a firm grasp on their childhood would have.” he says. “It’s evident that, at 96, he’s still a young person at heart.”’

When you flip through Irving Harper Works in Paper, it becomes more clear where Harper and other Modernist designers derived their inspiration. It’s obvious Harper loved the popular artists of his time, such a Miró, Kandinsky, and especially Picasso. He also reached back to Picasso’s original influences, such as African art.

Harper created a couple of horses inspired by Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting “Guernica.” Photo by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“I got the sense from talking to Irving that he was really interested in working these construction problems: How can I twist this, form that, and build that, working with paper?” Lasky says. “He created an engineering or an architectural-structural problem to solve within the aesthetics of different forms.

“He said he went through a bird phase, because he liked the variety of them. He liked cats very much. And it was hard to know, Was he interested in the spine or the shape of a cat? It wasn’t about something feral. It wasn’t about something related to a house pet. He was coming at the stuff from a design angle, how to make it stand, how to make it weather, how to make it big.”

In fact, Harper is so in love with his own artworks and having them around to admire, that he’s never considered selling them. In his T. interview with Guy Trebay, Harper asserted that he believes he’s come up with an entirely new way to use paper in artwork.

A detail of one of Harper’s construction-paper abstractions. Photo by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“It’s a unique use of paper in the sense that you couldn’t imagine somebody could make things that were so complex, or that they would spend that much time, cutting out little pieces of paper and scoring, folding, and gluing them,” Maharam says. “And when you see the elaborate detail and effort that went into these pieces, it’s just quite remarkable. That there were hundreds of them is even more remarkable. So obviously he’s a guy with a lot of mental energy that needed a place to go.”

The question is: Do these sculptures show that Irving Harper was shamefully overlooked throughout the 20th century, despite having a great artistic mind and being innovator along the lines of the Eames or Noguchi?

Harper’s clocks, like the 1961 Wheel Clock and the 1958 Sunflower Clock, stay true to his aesthetic and aren’t particularly easy to read. Images via Vitra.com

“Irving Harper worked in this extremely recognizable aesthetic,” Lasky says. “If anybody looks at his clocks for Howard Miller, they’ll go, ‘Oh, my God, that’s the ’50s.’ But did Irving invent that language or was he working brilliantly within it? Did he encapsulate it or did he generate it? I think he was probably more of an encapsulator than a generator. But I don’t know because his work has become the shorthand for the entire decade, which is not an easy thing to do. That is a remarkable achievement as a designer.”

Maharam—who’s been talking to Harper about exhibiting the sculpture after his death or auctioning them off to establish a Cooper Union scholarship—believes that Harper’s work was downright revolutionary in a time when all these Mid-Century Modern ideas were new.

These busts in Harper’s home are made from hat forms, construction paper, beads, shells, doll eyes, clock parts, tree branches, and even a mop head. Photo by D. James Dee, from “Irving Harper Works in Paper.”

“When you look at design now, there’s just such an incredible proliferation of products of all shapes, sizes, and forms,” he says. “But when you think about what a Marshmallow Sofa or the Howard Miller clocks that Irving came out with were in the 1950s, there was nothing else like that in those days. His influence was profound because his work was among those first dominoes that got people thinking and doing things differently. His pieces opened the eyes of consumers to a new idea of design.”

(“Irving Harper Works in Paper” is available from Amazon. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

'Mad Men' Prop Master Scott Buckwald Explains How He Re-Creates the '60s

'Mad Men' Prop Master Scott Buckwald Explains How He Re-Creates the '60s Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

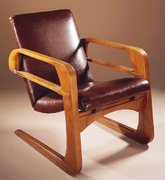

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA Pearsall FurnitureAdrian Pearsall (1925-2011) liked to make his furniture out of walnut so mu…

Pearsall FurnitureAdrian Pearsall (1925-2011) liked to make his furniture out of walnut so mu… SculptureFor thousands of years, sculpture was largely the province of human and spi…

SculptureFor thousands of years, sculpture was largely the province of human and spi… Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly …

Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article and wonderful art. I pre-ordered Harper’s book.

Wow fantastic article – thank you! I’ll be looking for the book and re-reading this article – so packed full of information.

extraordinary work at once marvelous and beautiful!

best not to play with matches

Fascinating article. Amazing sculptures! (hope they stay away from the sun so they will last!)

Great art.

Great Article and excellent information, Really Art has it’s own language.