On October 21, 1976, a small group of cyclists and a dog named Junior gathered on Carson Ridge, which rises just west of Fairfax, California. It was mid-morning and the sky was bright blue, a beautiful day for racing 50-pound vintage Schwinn Excelsior clunkers down Cascade Canyon Road, whose winding dirt surface plunges 1,300 feet in less than two miles, past serpentine outcrops, low-lying chaparral, and scattered oaks on its way to the confluence of San Anselmo and Cascade creeks.

“No one thought I should have been the guy to win their race.”

Among the bike riders assembled that Thursday morning, at an hour when most folks were dutifully toiling at their boring 9-to-5s, was Fred Wolf, an early off-road cyclist, and owner of Junior the dog; Charlie Kelly, a roadie for a beloved local rock band called the Sons of Champlin; Larry and Wende Cragg, who carried her trusty Nikkormat 35mm camera almost everywhere; and an airbrush artist and vintage-bicycle customizer named Alan Bonds, whose recorded time of 5 minutes and 12 seconds that day (average speed, about 23 mph) was good enough to take first place in a race that quickly became known around the world as Repack.

“It was kind of a fluke,” says Bonds today of his historic victory. “First of all, none of the really fast guys like Gary Fisher, Joe Breeze, and Otis Guy were there. I was basically racing against Fred, Charlie, and a few others, although they were the fastest guys I knew.” For the record, Gary Fisher would post the fastest time on Repack (4:22 on December 5, 1976), Joe Breeze would wind up second (4:24 on December 19, 1976), and Otis Guy would place third (4:25 on December 12, 1976).

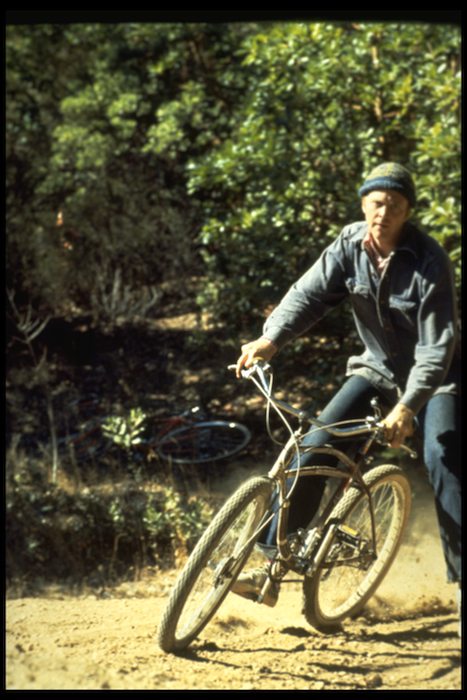

Above: Fred Wolf on a Breezer, photographed in 1979 at Camera Corner, where Wende Cragg took many of the best Repack shots. Top: Alan Bonds, who won the first Repack race, on his repainted Schwinn, circa 1978. Photos by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

In fact, Bonds won that first Repack race because he took a shortcut, which is not to say he cheated. “I normally rode with a group of guys who lived in Larkspur,” Bonds explains, citing a nearby town. “One day we were riding down Mount Tamalpais, and one of the hotshots in front of me, a rider named George Newman, was racing straight at a closed fire gate.” In those days, fire gates up on Mt. Tam, as the peak is called in Marin County, consisted of a horizontal steel pipe that was hinged to a post at one end and chained to a second post at the other. A second piece of pipe was welded to the horizontal pipe about halfway across, descending at an angle to the gate’s hinge, making the road impassable.

Or almost so. “George just went charging toward the gate,” Bonds continues, evoking the bone-shattering carnage that was about to ensue, “and then, at the last second, he slid under the pole with his bike, kicked himself up again, and took off down the road.” All these years later, the recollection gives Bonds pause. “I thought that was pretty phenomenal, so I practiced doing the same thing.”

Cascade Canyon Road had a similar gate about two-thirds of the way down, where Marin Municipal Water District land met the Cascade Canyon Open Space Preserve. On the day of that first Repack race, the gate was locked tight. “Everybody had to get off their bikes and run around the post the gate was chained to, cyclocross style,” Bonds recalls, referring to a forerunner of mountain biking in which riders often have to carry their bicycles around obstacles when riding laps around a course. “The footing was really bad, it was on a down slope, so it took about 20 seconds to get around the pole and back on your bike.”

Except, that’s not what Bonds did. “I wasn’t as good as George, but I managed to slide under the gate, stay on my bike, and push myself back up again the second I stopped. That’s why I won.”

Charlie Kelly skidding around Camera Corner on a blue-and-white Schwinn Excelsior. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

This month and next, such Repack tales of derring-do will be told and retold in three singular events. On September 13 and 14, some of the toughest cyclists on the planet will join the 38th Annual Pearl Pass Tour, which requires riders to pedal from Crested Butte, Colorado, to the top of 12,705-foot Pearl Pass before descending into Aspen. On September 17, Velo Press will publish Charlie Kelly’s much-anticipated history of Repack and the birth of mountain biking titled “Fat Tire Flyer.” And by October, the Marin Museum of Bicycling and Mountain Bike Hall of Fame is slated to open in Fairfax—until this year, the Hall’s collection had been housed in Crested Butte, where the Hall of Fame was founded in 1988.

All of these events, even the rugged ride over Pearl Pass, have major connections to Repack, which was held 22 times between 1976 and 1979, plus two more times in the early 1980s. In many respects, Repack launched mountain biking, although, strictly speaking, it is not where the then-nascent sport and recreational pastime was born. Still, the first Repack race was early enough that riders did not refer to the bikes they pointed down Cascade Canyon Road as “mountain bikes,” as the phrase had not yet been coined.

Historically, though, Repack was a relative latecomer to the practice of two-wheel enthusiasts riding two-wheeled machines in the dirt. Motorcyclists had been competing in off-road “scrambles” since the beginning of the 20th century, as had European cyclists in cyclocross races, which became popular in the United States around the same time bicycle motocross races (in which riders on smaller BMX bikes perform countless jumps while doing laps around a dirt track) took off in the 1970s.

Although Wende Cragg holds the record for the fastest woman down Repack, she got into mountain biking for the fun of it. Photo via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

Mountain biking proper also has its ancestral tree. In France, from 1951 to 1956, a group of 20 or so French cyclists founded Velo Cross Club Parisian, whose members performed jumps and other tricks on off-road bicycles outfitted with modified moped suspension forks to absorb front-end vibrations. In the United States, University of California at Davis professor John Finley Scott created a forerunner of the modern mountain bike in 1953 when he built his first “woodsie,” as he called it. In England, beginning in 1955, members of the Rough-Stuff Fellowship rode bicycles outfitted with fat balloon tires through places like the Chiltern Hills. And throughout the 1970s, people in the United States rode bicycles off road for fun in Santa Barbara and Cupertino, as well as in Crested Butte.

“That probably came from some sort of ad-hoc decision made under pressures I can’t possibly remember.”

Those Repack riders on that October morning (and no doubt that dog) weren’t overly focused on their place in this mountain-biking history, but by 1976, all of them were intimately familiar with the dusty fire roads that snaked around the flanks of nearby Mt. Tamalpais, where handfuls of cyclists had been riding off-pavement since the mid-1960s. “Actually, I remember driving my mom’s Chevy Impala out into the mountains,” says Gary Fisher, whose name has become synonymous with the sport thanks to the mountain bikes he and Charlie Kelly built, using Tom Ritchey frames, in 1979. “In the mid-’60s, you could drive anything out there. Then, they put chains up everywhere, so a bike was the only way to get around.”

For Fisher, the hills of Marin were an unsupervised playground, which he explored with a group of cycling buddies from Redwood High School called the Larkspur Canyon Gang, who rode old Schwinns and other modified clunkers. “The scene was like, you know, go out into the mountains, drink some beer. The first hour would be cocktail hour, when you’d ride around on this big wide stretch of fire road.” In short, it was a place where high-school students went to party.

Joe Breeze modified a 1941 Schwinn for riding around Mt. Tam by upgrading the front drum brake and adding a steel reinforcing bar to the handlebars. Photo by SFO Museum.

“I’d been a road racer for a long time already,” Fisher continues, “and I’d already been exposed to cyclocross. So I’d ridden a cross-bike out in the woods before, but it was all flats all the time—it was ridiculous, you couldn’t go fast. That’s what was so fun about the Canyon Gang. They went super fast.”

Wende Cragg, one of the few female cyclists in the early days of mountain biking (Jacquie Phelan was another), definitely did not get into off-road for the speed. “I fell into it quite by accident,” Cragg says. “Fred Wolf was my neighbor. He talked my ex-husband and I into putting together mountain bikes. On my first ride out, I was terrified—my bike weighed about 55 pounds, so it was hard to handle. I thought, ‘God, I’m never going to get back on this bike again.’ But Fred happened to be best friends with Charlie Kelly, who happened to be good friends with Gary Fisher—it was like a domino effect. Fred coaxed me back out. Little by little, I kind of acclimated to it, and slowly, I got stronger and more confident. Before I knew it, I was hooked.”

In part, Cragg was attracted to the freedom she felt riding a bicycle in the hills. “I lived right next to an open-space area, so I had immediate access. There was no reason not to take advantage of it. We had the whole place to ourselves, plus there was Mt. Tam. None of us really worked, so we had the flexibility to just take off, and for a couple of years, that’s all I did, really, just ride, ride, ride. We’d pack a lunch and a Frisbee, bring the dog and some bud, and go. It was like we were exploring a foreign land. Mountain biking was not even a thing yet, so we were pretty much invisible.”

Gary Fisher’s modified 1940s Schwinn featured front and rear derailleurs and motorcycle brake cables and levers. Photo by SFO Museum.

But for Cragg, mountain biking was about more than just drinking beer, smoking pot, and enjoying the escapist pleasure of achieving anonymity on two wheels in the hills. For her and many others, riding a bicycle out in the woods, away from pavement and cars, was a portal into a more spiritual world. “It totally changed my life,” she says. “I can’t imagine what my life would be like without having been introduced to the mountain bike. It completely enveloped me. I swear, I just became my mountain bike. When I was growing up, I was really into roller skates. I’d sleep with my roller skates on, ready to roll as soon as I got out of bed. Literally. I would roll down the hallway and out the door. I became as passionate about mountain biking as I had been about roller skating. So sure, it was a way to escape, have an adventure—all that stuff all rolled up into one. But there was also something so soulful about being out on a trail on a bike all by yourself, out in Mother Nature, communing with this great thing in such a quiet, passive way.”

That’s what mountain biking meant to some people. For others, not so much. “The reason mountain biking is so popular,” says Charlie Kelly, “is that it’s one of the only ways in modern life that you can turn on your adrenaline pump, and leave it on for a long time. You can go big-wave surfing or skydiving, but downhill bike riding gives you all the adrenaline you can handle. I mean sure, skiing is as adrenalized, but most people can’t do it at a high level for more than five minutes, it’s physically difficult. But anybody can ride downhill for five minutes on a bike. That’s the attraction, not so much the competition but that you can get in the zone and stay there for a long, long time.”

With 10 victories and almost twice that many races to his credit, Joe Breeze rode a lot of bikes down Repack, including this 1944 Schwinn Excelsior modified by Otis Guy. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

In Marin, one of the best places to get in the adrenaline zone was Cascade Canyon Road, which had been a favorite of the hardest of the hardcores since the early 1970s. In fact, even its nickname, Repack, which people like Charlie Kelly and Fred Wolf started using some time after 1974, was hardcore, describing the maintenance required to keep a coaster-brake bike’s rear hub spinning after a couple of descents.

Coaster brakes got a serious workout on the way down Cascade Canyon Road. By the time riders arrived at the bottom, their bikes’ rear hubs would actually be smoking from the pressures they were subjected to, as hot as a frying pan to the touch. The smoke, of course, was evidence of the lubricants inside the hub vaporizing, which meant the inside of the hub was essentially drying out. Thus, if you didn’t want your rear hub to seize up on you without warning, you needed to repack it with fresh, cool grease.

For a while, Charlie Kelly used old Bendix and Mussleman brakes on the clunkers he rode in the hills, although he always wanted a vintage Morrow, which was considered the toughest and most durable coaster brake around but was just about impossible to find. Kelly could tear apart and repack a hub with the best of them, but by the time of the first Repack race, he had moved on to more sophisticated technology, which he and Breeze and Fisher had glimpsed in December of 1974, when they attended the West Coast Cyclocross Championships in nearby Mill Valley.

Joe Breeze riding Breezer #1 on Repack, 1977. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

As luck would have it, Russ Mahon and several other cyclists from Cupertino attended the championships, too. Just as the Larkspur Canyon Gang had their nom de guerre, Mahon and his posse called themselves the Morrow Dirt Club, named after the legendary coaster brake Kelly and so many others coveted. For the Cyclocross Championships, Mahon rode a Montgomery Ward Hawthorne, tricked out with big 26-inch wheels, 10 speeds, and cable-operated front and rear drum brakes.

Bikes with hardware like derailleurs and hand brakes were certainly not new to cycling. For example, cyclists competing in the Tour de France began using derailleurs in 1937. Indeed, on the day of the West Coast Cyclocross Championships, Gary Fisher, who was competing that day, arrived on a cyclocross bike that had a derailleur. But people didn’t do this sort of thing to balloon-tire bikes in 1974, so for Kelly, Fisher, and Breeze, the Cupertino bikes were more than a little intriguing. Members of the Morrow Dirt Club went their separate ways shortly after the Mill Valley championships, but the Marin County riders had seen the future, and they liked what they saw.

Kelly didn’t need to be shown the future twice. “By 1976,” Kelly says, “a whole bunch of us had upgraded our clunkers to 10-speeds, with drum brakes in the front and rear. That’s what I was riding on the day of the first Repack. It was probably a Schwinn of some sort, although I didn’t pay much attention to the labels back then so I don’t really know. In those days, a bike did not last long enough under me to get too sentimental about it. I just destroyed frames, repeatedly.”

Joe Breeze with Breezer #1 at the bottom of Repack, after winning the race on the bike’s first ride down the road, 1977. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

Repack, then, did not mark the first time cyclists in Marin starting riding their bikes into the hills, nor was it the first time cyclists in California had tricked out fat-tire bikes with better hardware. But the competitive nature of Repack drew attention to mountain biking in a way that riding around in the hills drinking beer with your buddies did not. And once people in Marin like Alan Bonds, Joe Breeze, Charlie Kelly, and Gary Fisher began to customize, and then build from scratch, bikes designed to conquer Repack, the whole thing jelled.

That a race like Repack evolved in Marin is kind of ironic if you know anything at all about Marin. Repack was an aggressively competitive event, in which racers, some of them road-racing professionals, mapped out the course in advance and made major modifications to their bicycles (putting heavy-duty motorcycle levers on their handlebars; installing oversize tandem-bike drum brakes in the rear) to gain an edge over their competitors. In contrast, 1970s Marin was the laid-back land of 420, a Shire-like refuge for the tattered, freak-flag-flying remnants of the hippie counterculture of the 1960s.

Even in mellow Marin, though, Repack brought out the competitive side of pretty much everyone, as Alan Bonds found out when it was revealed on that October morning that his was the winning time in the first official race down Repack.

This 1984 map of Repack was created based on information provided by Joe Breeze, with artwork by D.L. Livingston.

“I shared a house with Gary Fisher and Charlie Kelly at the time,” says Bonds, “but when I won that first Repack, people said, ‘Oh, that can’t happen, that’s not right.’ No one thought I should have been the guy to win their race.” Cries for a rematch were immediate, and a second Repack was held the following Tuesday, just five days after the first. “They figured Bob Burrowes was faster than me,” Bonds says, “and sure enough when Bob showed up for the next race, he beat my time by 22 seconds. Everything was fine after that.”

The intensity of the competitive spirit Bonds observed in the hills of Marin may be why he didn’t tell Wolf, Kelly, or the Craggs about his George Newman move under the fire gate that morning, at least not right away. “Nobody saw it the day it happened,” Bonds explains today. “Telling them I did it wasn’t something that came up until years later.” By then, Bonds had four Repack victories under his belt, if you count his 4:39 time on April 10, 1977, a tie for first with (wait for it) Bob Burrowes.

Which brings us back to that gate. “Within a matter of days after that first race,” Bonds remembers, “Wende or Larry Cragg found a ring of keys at a fire gate under a lock, just laying there on the ground. One of the keys was the master to all the locks on all the fire gates in the Marin Municipal Water District,” including the one on Cascade Canyon Road.

As Repack became a regular event, riders would load their bikes into the back of Fred Wolf’s one-ton flatbed to hitch a ride to the lot at Azalea Hill. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

Wende Cragg does not dispute that she found the keys, although she’s not certain it happened quite in time for the second race. In addition, when she found the keys, she wasn’t even on water-district property. “Larry and I found them after a wildfire near Bear Valley,” she says. For those not familiar with Marin County’s many natural wonders, Bear Valley is a part of the Point Reyes National Seashore, about 15 miles northwest of Fairfax. “We’d gone out there right after they re-opened the area. It was on the Coast Trail,” a hike of several more miles to the west, “that we spotted the ring of keys. We grabbed them, not really thinking too much about what they might open. As it happened, the ring contained a master key that opened the Repack gate. Having the gate open gave riders the psychological advantage of not having to guesstimate its location or having to dismount, which took several seconds off everyone’s clocked time. I wonder what happened to that set of keys?” she adds.

Meanwhile, the rest of the San Francisco Bay Area cycling community was starting to hear about these crazy races up on Repack. Cyclists from Marin and beyond wanted in on the action, which is why a third race was held just four days after the second. That race attracted the aforementioned George Newman, who finished fourth with a time of 5:17, as well as a couple of other members of the Larkspur Canyon Gang. But the big dog on Saturday, October 30, was Joe Breeze, who clocked a respectable 4:56 on a seven-speed, 26-inch wheel Schwinn Excelsior for the first of his record 10 Repack wins.

To meet Joe Breeze today, you wouldn’t peg him as the guy who won more Repacks than anyone else, and whose personal-best time down Cascade Canyon Road (4:24) is just two seconds behind the course record set by Gary Fisher (4:22). Truth told, Breeze looks more like the curator of a bicycling museum in Marin, which is what he happens to be, than a calculating speed demon, which is what he once was.

From left to right, Joe Breeze, Wende Cragg, and Fred Wolf riding up Pine Mountain Truck Road from the Azalea Hill parking lot to the top of Repack. Photo via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

Racing, though, was in Joe Breeze’s blood. “My dad, Bill, raced cars when I was a kid,” Breeze says. “He won the first sports-car race in northern California. I grew up with that legacy, and had this need for speed from an early age. My dad could see that, so he didn’t allow my brother, Richard, or I to get our drivers licenses until we were 18. But by then it was like, ‘I can get anywhere on a bike, so why bother?’ I didn’t get a driver’s license until I was 26 years old.”

“It was just scary enough that it required a lot of bravery.”

Instead, Breeze raced road bikes, he skied, and he rode a unicycle, anything that kept him in motion, ideally at high velocity. In the early 1970s, encouraged by his friend Marc Vendetti, Breeze started riding a 1941, balloon-tire Schwinn on Mt. Tam, too. “When fat-tire racing came along,” Breeze says of his first awareness of Repack, “I was the number-one draft pick. I took it really seriously. I would walk up and down the course to map it out, to memorize it. It was like 51 turns or something, so it was important to know what was around one turn and not around another. I made a science out of it—the family name was on the line.”

“The course was not tough at all,” says Gary Fisher of the quality of the road that first year. “What made it tough were the competitors, what made it hard was that it was a race, man. Somebody was trying to beat you, that’s what made it hard. I was a really speedy bike racer at the time, on road and off, and a really good bike handler. You had to be a good bike handler because Repack was a pedaling race; you had to pedal constantly. But we practiced a lot, we got really good at that course. That was part of it. I must have done that course a thousand times back in the day. The day I set the course record, it had rained a few days before and there was a tailwind. I swear it was favorable conditions that made my time a hard one to beat.”

Riders gathered at the top of Repack for this 1977 race include Charlie Kelly (in red hat with notebook), Alan Bonds (wearing a gray sweater in the foreground), Joe Breeze (wearing lots of denim in the background), and Gary Fisher (also in denim, wearing one of his signature ski caps). Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

“The road was in real good shape,” agrees Alan Bonds. “It was just about as smooth as a sidewalk all the way down. And if you stayed on the line,” the main route down the road, “then you could go really, really fast. I figure the top speed anyone hit was around 41 miles per hour, and the average of Gary Fisher’s record run was about 28 miles an hour. But if you got off the line at all, then you could probably expect to have a slide out, run into a bush, or something.” Yes there were injuries, but remarkably few.

“It was just scary enough that it required a lot of bravery,” Bonds continues, “and generally you had to be pedaling as hard as you could between every turn, all the way down. The level of energy exerted pedaling downhill was phenomenal. I mean you’d be seeing stars, blue in the face, by the time you were halfway down. That’s why the fastest guys were the professional road-racing athletes. When they trained, they would see how many six- or seven-second bursts they could do consecutively in a small period of time. That’s what you had to do going down Repack. Every time you were clear, you had to be hammering. The racers just had more conditioning; they were better at it.”

By 1979, Repack had become a phenomenon, which meant that Charlie Kelly, as the heart and soul of Repack, and the keeper of its logbooks, was sought out by a camera crew from the local TV show “Evening Magazine.” Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

For Cragg, who still holds the record for a female rider (5:29, for an average speed of about 22 miles per hour) but wasn’t into the competitive aspects of mountain biking in the first place, the vibe around the racing was sometimes a bit much. “There was a lot of testosterone at the top,” she allows. “The guys were dead serious about wanting to get the title. It would just be so tense.”

It was also dangerous. “I remember the couple times I raced, I had trouble keeping my feet on the pedals. We didn’t have straps back then. So it was like your feet would be slipping off the pedals as you were trying to stay composed and think about what you were doing. The last time I crashed, I went into this cavernous kind of rut that I had trouble getting out of because it was pretty freaking deep. That was the day I decided I’m not doing this again. I was lucky to walk away without any broken bones. Yeah, there were some terrifying moments on that race course.”

George Newman, who taught Alan Bonds how to slide under fire gates, raced Repack for the first time on October 30, 1976. Two races later, he won with a time of 4:47. Via Charlie Kelly’s Repack Page.

Kelly remembers the ruts, too. “Back in the day, Repack had a lot of deep ruts running parallel to the line. They aren’t there now. The road is actually in much better condition. But that was part of the attraction back then, you know?”

“In the late 1980s,” Bonds adds, “the ruts were getting so bad the water district had to go up there and regrade it. When they did that, they put in some forest service water bars across the road. It was like putting a series of speed bumps on Repack. The water bars would launch your bicycle 20 feet into the air if you were going fast enough.”

By the end of 1976, some 90 race times had been recorded in nine Repack races, each of which was organized by Charlie Kelly, who’d call people on the phone to tell them the race was on, and Fred Wolf, who had a one-ton flatbed that was used to ferry riders as far up Carson Ridge as they were allowed to drive (from there, cyclists still faced another 20 minutes or so of climbing to get to the starting line at the junction of Repack and Pine Mountain Truck Road).

Gary Fisher giving a 1941 Schwinn a workout at Camera Corner, 1976 or ’77. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

Eventually, Kelly and Wolf purchased a matching pair of digital timers to ensure that the timekeeping for Repack was as state of the art as possible. The drill was simple: Kelly usually manned the timer at the top of the hill while Howie Hammerman, a sound engineer at Lucasfilm who was a friend of several riders, was often in charge of the timer at the bottom. After the timers were synchronized, Hammerman would be given 10 minutes to ride to the bottom, which was deemed enough time for him to get down safely without wiping out, but not so much time that everyone up top would be twiddling their thumbs for longer than necessary.

Meanwhile, riders (that first year there were never more than 21 in a given race) were assigned preset start times at two-minute intervals—new riders and those with the slowest times from previous races went first, winners went last. Because the start times were preset, each rider was given an index card with his or her start time written on it. To prevent false starts, Kelly would physically hold the rear wheel of a racer’s bike until their start time flashed on his timer, then he’d let go. At the bottom, as each rider crossed the finish line, Hammerman would jot down their time, take their card with their start time written on it, and subtract. Race times were given to riders on the spot, and the winner was announced shortly after the last racer had arrived at the bottom.

Riders await race results at the bottom of Repack. On this day, Vince Carlton did timer duties at the finish line. Photo by Joe Breeze via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

When the mountain-biking creation myth is told around a crackling campfire, these are the sorts of details one hears. But fully a month before Alan Bonds was performing his controlled slide under a steel fire gate to win the first Repack race, a high-altitude group of cyclists in Crested Butte had already pushed themselves to the limit, albeit in a uniquely Rocky Mountain way. They called their non-race, off-road-cycling endurance event the Pearl Pass Tour.

About the only thing Pearl Pass had in common with Repack was that both happened on bicycles. It wasn’t just that Crested Butte locals spelled klunkers with a “k” instead of a “c,” or that for them riding a bike was a matter of necessity rather than a quest for adrenaline or a chance to commune with nature—when they weren’t covered by snow, the roads in Crested Butte were usually so full of potholes, riding a bicycle was actually a safer way of getting around town than driving a car or truck. And it wasn’t even that the real reason 15 cyclists decided to ride their bicycles 40 tough miles over Pearl Pass in September of 1976 may have been because they were pissed off that a bunch of frat-boy types from Aspen, on the other side of Pearl Pass, had made a big deal about doing the exact same thing on their motorcycles a few weeks before, taking over Crested Butte’s favorite bar, the Grubstake Saloon, to boast, brag, and generally carry on.

Okay: Maybe it was that.

“At that time,” says Don Cook, whose first Pearl Pass Tour was in 1980, “trail riding here was almost nonexistent.” Little wonder, then, that only two of the 15 cyclists who began that first expedition over Pearl Pass on one-speed klunkers, Bob Starr and Rick Verplank, managed the ride unassisted by the support vehicles that also carried food, beer, wine, champagne, schnapps, and, for some reason, a bathtub.

If you’re getting the sense that the first Pearl Pass Tour was little more than an excuse for a rolling party above the timberline, you’re not too far off the mark. In fact, there was no 1977 follow-up to the 1976 tour because most of the people who had taken part in the first Pearl Pass ride were fighting wild fires in the San Juan Mountains outside Durango, Colorado, as well as other places around the West. “Work was hard to find here,” says Cook, “so being in the firefighting squads was really good money.” In short, the 1977 Pearl Pass Tour was canceled on account of wild fires.

Riders line up outside the Grubstake Saloon in 1978 for the Third Annual (second actual) Pearl Pass Tour in Crested Butte, Colorado. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

Despite this paltry track record (one ride and just two finishers in two years), the legend of Pearl pass made its way to Marin and Charlie Kelly. Gary Fisher takes the story from here: “Charlie Kelly calls ’em up and says, ‘Hey man, we’re from California, and we want to come to do the ride.’ Charlie had the balls to call people up and say, ‘Hey, let’s do this.’ That’s sorta how things get started, you know?”

“I made the phone call, but five of us went,” says Kelly. “Richard Nilsen had written an article for ‘CoEvolution Quarterly’ in early 1978 that said these guys in Crested Butte were doing stuff very similar to what we were doing on Repack. So I called ’em up and said, ‘Hey, is this thing happening again?’ And they said, ‘Oh, yeah, yeah.’ It wasn’t, of course, but we went out there anyway, and when people travel 1,000 miles to ride some bikes, you ride some bikes. That’s how it happened. It certainly wouldn’t have taken place if we hadn’t shown up.”

“There was a lot of testosterone at the top.”

“They were wonderful,” says Wende Cragg of the riders she met in Crested Butte. “I still have the greatest impression of rolling into town with our bikes on the roof of the car. I think we had rented a station wagon or something to get ourselves out there. It was just Charlie, Joe, Mike Castelli, and me. Gary flew in from New York. We drove to somewhere outside of Crested Butte and met up with Mike Castelli’s friend Richard Nilsen, who wrote the article for the ‘CoEvolution Quarterly,’ which was officially the first article about mountain biking. The people were so nice, and they were so blown away by our bikes. We had chromoly [as in chromium and molybdenum] bikes by that time, so they were like, ‘Wow!’ They treated us like rock stars.”

“It was a trudge,” recalls Kelly of the ride itself, “followed by a really rough downhill. But I didn’t mind trudging because it was an adventure that included bikes, it was all part of the deal.”

The descent from Pearl Pass down into Aspen is a rocky nightmare, but the scenery is stunning. Photo by Wende Cragg via Rolling Dinosaur Archive.

“Crested Butte is just the most knockout, gorgeous place to ride,” adds Cragg, “and the climb up to the base camp was great. But the next day was the God-awful climb to the top of Pearl Pass, and it was a heart-and-lung breaker for those of us who were used to riding at sea level. We were dying. And then, of course, when you got to the top, there was nothing there but rock. But when we rolled into Aspen and had beers at the Jerome, it felt wonderful. I probably did four Tours in total, so I saw it evolve, but the initial one was a little homespun event that just kicked it off. I’m so glad that they’re still doing it.”

“Eventually, the Tour became the province of the local cross-country skiers, who are exactly the same people who ride mountain bikes,” says Kelly. “There’s a big contingent of them in Crested Butte, but they weren’t part of the original thing. As soon as mountain bikes arrived in Crested Butte, the cross-country ski guys all took it up. And that’s where Don Cook and his crew came in. They’re a bunch of athletes, real athletes. As soon as Don Cook saw the Tour, well, he was all over it.”

“In 1979,” says Cook, “I stood on Elk Avenue, the only paved street in Crested Butte at the time, and watched the guys and a couple girls leave town for the Pearl Pass Tour. And I was like, ‘That’ll be me next year.’ I didn’t feel like pushing my one-speed up over the Pass like the guys in 1976 had done, not after I saw the machines that were sitting on Elk Avenue in the fall of ’79. I’m looking at these things, going ‘Oh, my goodness. What have we here?’ Their bikes had gears, drum brakes, and motorcycle levers, just the kind of really cool stuff a young 19-year-old would be dreaming of. And so I said, ‘That’s me, I’ll be there next year,’ and watched them ride off down the street. And I think I took my one-speed, went out and did a ride that afternoon and determined to build a bike over the winter.” Which is exactly what Cook did. In fact, Cook is still involved with the promotion of the Pearl Pass Tour today, and until its recent relocation to Fairfax, he was the co-director of the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame with his wife, Kay Peterson-Cook.

Before Breezers and the MountainBikes made by Charlie Kelly and Gary Fisher, Schwinn Excelsiors were the bikes of choice for many Marin riders, including (left to right) Alan Bonds, Benny Heinricks, Ross Parkerson, Jim Stern, and Charlie Kelly. Via Charlie Kelly’s Mountain Bike Hubsite.

The hardware that infatuated Cook had evolved incredibly since the first Repack. “That 1978 Pearl Pass event was really the start of the technology being taken to the terrain,” Cook says. “Mt. Tam’s a wonderful mountain. It has lots of great trail- and fire-road riding on it. But it wasn’t as rough and rocky and big as what we have out here. Pearl Pass upped everyone’s game, big time. Since then, when builders have needed to test a bike fully, they come to Crested Butte and do the Pearl Pass Tour, because going down the Aspen side of Pearl Pass will tell you exactly what you need to do to improve your bike. Those same rocks are only one thousandth smaller since Joe and Gary rode here.”

“The scene was like, you know, go out into the mountains, drink some beer.”

In fact, the chromoly bikes Cragg remembers riding in Crested Butte in 1978 were the beginning of a technology revolution in cycling. They had been built by Joe Breeze, who appears to have been the first person to build a frame designed for mountain biking, although even he didn’t call it that in the fall of 1977 when he began work on his first Breezer. With its distinctive twin-lateral tubes, the first nickel-plated Breezer was commissioned by Charlie Kelly. Its frame was made out of chromoly aircraft tubing, which was stronger, but not much lighter, than the steel used on frames made for those Excelsiors and Hawthornes. In all, Breeze made 10 Breezers between the fall of 1977 and the spring of 1978. Breezer #1, the prototype, which Breeze rode in Repack #15 in the fall of 1977 for a winning time of 4:25, is now in the Smithsonian. Breezer # 2 remains in the collection of Charlie Kelly.

“The Breezer bikes were obviously the next step,” says Kelly. Breeze’s bikes were unarguably awesome, with their unusual frame design, Campagnolo seatposts, Brooks saddles, and SunTour shifters on Magura motorcycle handlebars, which were naturally fitted with Magura motorcycle brake levers. But Joe Breeze was a perfectionist (Kelly called him “the mad scientist”), which meant he didn’t exactly work quickly. “Gary was looking for someone to build him a custom bike, but Joe was going to take a while, so Gary farmed the job out to a couple of different builders, including Tom Ritchey, to see who could do it first. In the end, Tom Ritchey built three bikes, one for Gary, one for himself, and one for another guy in Fairfax. Tom Ritchey got Gary his bike first, so that’s how Tom got into it.” And that’s how Charlie Kelly and Gary Fisher became accidental business partners.

Ritchey #1, made by Tom Ritchey, 1979. Tom Ritchey would supply frames to Charlie Kelly and Gary Fisher, who sold the finished bikes as Ritchey/MountainBikes. Photo by SFO Museum.

Ritchey was a whiz-kid, lightning-fast frame builder from Palo Alto, just north of Cupertino. “Tom thought, ‘Well, these guys want frames, so I’ll make some more,’” remembers Kelly, “but he didn’t really want to build out the entire bikes, because that’s a real pain. The frame is one thing but the bike is another, and so, in desperation, Tom said, ‘Hey Gary, can you help me get rid of these frames?’ And Gary said, ‘Hey Charlie, can you help me get rid of these frames?’ And from that minute on, I guess we were in business, but there was not really what you’d call a business plan, it just kind of happened. The whole thing was kind of flawed and doomed from the start, but it did change the world, and who gets to do that? So, I’m not unhappy about it.”

What Kelly professes not to be unhappy about is what happened to him as the co-founder with Fisher of a company called MountainBikes, which finally gave a name to what he, Wolf, Bonds, Fisher, Breeze, Cragg, and many others were riding up the hills of Marin. “In 1979, Charlie Kelly and I started a company called MountainBikes,” says Fisher. “That was an original name at the time. Before that, people called them all kinds of stupid things.

“What we did basically,” Fisher continues, “was make a lot of bikes. The first year we made 160 bikes, the second year we made 1,000. A thousand bikes! All these other guys were dickin’ around, you know, making 10 bikes a year. But I was like, ‘Man, you gotta make it happen!’”

In 1980, Marin County’s Cove Bike Shop, run by the Koski family in Tiburon, introduced the Trailmaster, which influenced Japanese manufacturer Shimano, who sent representatives to the shop in 1982. Mountain biking quickly went global. Photo by SFO Museum.

For a while, Kelly and Fisher did just that, using mostly, but not exclusively, Tom Ritchey frames. Sometimes their advertisements would brand their company as MountainBikes (one word), sometimes the name was broken in two (as in the company’s first ad). Later, bikes were marketed as Ritchey/MountainBikes, which led customers to assume that Ritchey ran the company when, in fact he was essentially just the frame guy.

“That probably came from some sort of ad-hoc decision made under pressures I can’t possibly remember,” says Kelly with a laugh. “It was a very fluid environment, and we were making stuff up on the fly. Decisions were made without much thought, and that might have been one of them, but the thing is that Tom was his own entity called Ritchey; Gary and I were MountainBikes. The frames came to us, we assembled the bikes, and the product was called the Ritchey/MountainBike. Which is still a vague thing: Is that a generic term or a company name? But that’s water under the bridge. I got chapters in my book on all this stuff.”

The Kelly/Fisher partnership ended in 1983, and a decade later, Fisher ended up selling MountainBikes to Trek, which now has a brand called the Gary Fisher Collection. “People call me the ‘father of the mountain bike’ and all this stuff, and they say to me, ‘Gary, thank you, thank you for making a mountain bike. You’ve changed my life.’ And I say to them, ‘Hey, man, if it weren’t for you wanting to ride my bikes, I’d be nothing, you know? This whole thing would be nothing.’ And do you know what the biggest innovation of the last 10 years has been? The trail. Think about it. There are all these great trails now. Riding a great mountain-bike trail makes you feel like a genius.”

An Alan Bonds clunker, photographed by Charlie Kelly on Mount Barnaby in Marin. Via Charlie Kelly’s Mountain Bike Hubsite.

Joe Breeze started his own bike company, too, which he continues to run even while juggling his duties at the Marin Museum of Bicycling, where he’s not only the curator but a board member, too. While Breeze began making bikes that were tough enough to ride down Repack or over Pearl Pass, his focus of the past few decades has been on bikes that are awesome enough to get people out of their cars. “It’s always been about the everyday use of the bicycle,” Breeze says of his on- and off-road pursuits. “That was really the glue that held the whole family of cycling together, that was the bond.”

That family of bicycles will be on full view at the Marin Museum of Bicycling, although mountain bikes will definitely have a place of prominence. “Mountain biking is going to be important, no doubt,” says Marc Vendetti, Joe Breeze’s old friend and now his fellow board member at the Museum. “But we really want the museum to be about all bicycling. So we’re going to work very hard to have a balanced exhibit. To that end, we’ve got this great collection from David Igler and his father, Ralph, that shows the progression of bikes from the middle 1800s into the modern age.” Highlights of the Igler collection include an 1868 Michaux “boneshaker” velocipede, an 1890 rear-suspension Rambler, and a 1900 Racycle track bike. “So people who come to the museum,” says Vendetti, “will leave, I think, with a really broad idea of how bikes began and what the milestone steps were in their evolution.”

Some people call Gary Fisher the father of the mountain bike, but it may have been this guy, Russ Mahon, seen here in a photo from 2006 by Stephen Wilde.

Wende Cragg remembers when Otis Guy (whose third-best time overall in Repack is less than a second slower than Joe Breeze’s) saw all this coming. “When this whole clunker thing got started,” Cragg says, “Otis Guy, who’s one of my neighbors, would always say, ‘Now, don’t tell anyone. You’ve got to keep this secret, because once this gets out, if this thing takes off, it’s going to ruin it for us!’ He could see the domino effect—that once someone found out about it, they’d turn somebody onto it, and then that person would turn somebody else onto it, and so on. It was like a fire had been set and there would be no stopping it.” Today, Guy is also on the board of the Marin Museum of Bicycling.

As for Bonds, the guy who won the first race that everyone says started it all? He just delivered a couple more “authentic replicas,” as he calls his customized clunkers, to a client in Texas. While he hasn’t been down Repack in about a year, he still gets out into the hills. “I still ride a mountain bike,” he says. “I like to ride relatively moderate trails for exercise, so I can stay healthy. That’s about it. I’m not fast or anything—I ride a bike.”

(To learn more about the early days of mountain biking, order a copy of Charlie Kelly’s “Fat Tire Flyer.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

The Unfiltered History of Rolling Papers, Plus Tommy Chong's Big Fat Jamaican Vacation

The Unfiltered History of Rolling Papers, Plus Tommy Chong's Big Fat Jamaican Vacation

Headbadge Hunter: Rescuing the Beautiful Branding of Long Lost Bicycles

Headbadge Hunter: Rescuing the Beautiful Branding of Long Lost Bicycles The Unfiltered History of Rolling Papers, Plus Tommy Chong's Big Fat Jamaican Vacation

The Unfiltered History of Rolling Papers, Plus Tommy Chong's Big Fat Jamaican Vacation American Picker Dream, Part I: Mike Wolfe On His Love Affair With Bikes

American Picker Dream, Part I: Mike Wolfe On His Love Affair With Bikes BicyclesThe precursor to the modern-day bicycle was the 1817 Draisine, named for it…

BicyclesThe precursor to the modern-day bicycle was the 1817 Draisine, named for it… SchwinnIf you grew up in postwar America and rode a bicycle, chances are pretty go…

SchwinnIf you grew up in postwar America and rode a bicycle, chances are pretty go… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Gary Fisher is credited as the inventor of the mountain bike because he was the first to turn it into a business with his friend Charles Kelly. I am talking about a “real” business, intent on massive expansion, not just an individual making a few limited-edition bike frames. I used to see Gary at the local coffee shop entertaining groups of Japanese men in business suits, convincing them to manufacture mountain-bike-specific components. Then, he had a “boiler room” (I think that is what they are called) in the back of his shop, people on phones calling bike shops and manufacturers to sell the components. Later I saw two Fisher team members at a trailhead, with some Japanese men in suits, and devices attached to the bicycles’ shift cables, to measure gear shifting. This turned out to be the original research for index shifting, which almost every bicycle rider takes for granted nowadays. Gary was the go-to person for research and development, and he still is cycling’s premier evangelist, traveling the globe to promote the sport. He had help, of course, and others had been putting together this type of bicycle for quite a while previously, but Gary’s work made the mass marketing of mountain bikes possible. It’s sort of like Edison and the light bulb. We tend to remember the person who turned an idea into a common product that anyone could buy. Edison said it was 10 percent inspiration, 90 percent perspiration, and Gary did a lot of that 90 percent stuff, behind the scenes, in the manufacturing and marketing end. Now the default bicycle people start out with is generally a fat tire machine (as opposed to the formerly dominant skinny-tire 10-speed). These bikes are more comfortable, more upright posture, etc. This helped boost bicycle sales, got more people out there with a healthy sport and leisure activity. We all should be grateful for the work Gary Fisher has done and continues to do.

Just an FYI…while Gary may have been involved with the early development/testing of “SIS”, I was in on the beginning of the actual concept. I keep after Shimano to develop their “Positron” shifting for mountain biking, which lead to the development of “SIS” or as we call it now–index shifting.

Just wanted to set things right.

I think it was Aki from Shimano who actually did the design of of SIS.

Yes Gary Fisher was the father of Mountain Biking.. very cool to learn something new!!!

What they back then, and up to the mid 90s orr so, referred to as a mountain bike is what is now called a “hybrid/trek” bicycle.

When I was 12 my first job was working at a bike shop in Lake Tahoe, I’m 60 now and really enjoyed the article. These bikes are beautiful and the photos are terrific.

Very thorough piece to be written from so many different sources.

My book on this adventure will hit book stores in a few weeks, entitled Fat Tire Flyer.

Moving on to other things, the YZ450F’s suspension is good in stock form. Just make sure it has the correct spring rates for your weight and riding style. The handing on this bike is said to be an issue. Supposedly the steel frame was to blame and made it feel heavy and turn slower. I mentioned that 2006 is when Yamaha switched to aluminum frames for its four-stroke motocross bikes, and doing this resulted in better turning and handling for this bike. 2010 is really when handling was a positive for the YZ450F with the new bilateral-beam frame and centralized weight. It made it feel more like a two-stroke, but not quite because of its weight.

OMG !! None of them were wearing helmets :-o

SAM BRAXTON OF MISSOULA(MT) WAS NOT A HIPPIE DAREDEVIL BUT PROBABLY MADE THE FIRST MOUNTAIN SUITABLE BICYCLES IN THIS AREA IN THE 80’S.

What’s left to say. A great article, great pics, a neat part of biking history. And, as one person already mentioned, “NO helmets.” From personal experience, I’m glad I wear one today. Thanks for this wonderful piece.

It’s funny to think of those long haired boys being full of testosterone!

Good read! I remember the good old days, c. early ’70’s, riding my road bike — sew-ups and all– on the dirt at Lake Tahoe. Trashed many a tire and wheel. Thank you guys for giving us the dirt bikes — still ride ’em when I can in the hills in my backyard here in Central WA, where I’m a real wimp on the downhills (and I do wear a helmet), but I love getting out there, and it sure beats hiking. Anxious to see Charlie’s book.

Geoff Apps and his Cleland was another pioneer during this exact time. But in England, with a much different take on frame geometry and types of trails he was riding. We were really close to having 650b be the MTB tire standard, his story is a good read.

Teri-if you read LONG HAIRED boys, you wonder about the testosterone. If you read it long haired BOYS, well, BOYS will be BOYS!

The inventor of the first Mountain bikes was LES DEGAN who built downhill bikes in his house on Mono Ave in Fairfax. He supplied his friends with downhill bikes when we threw them in a truck and we drove up to the observatory on Mt Tamalpais. All jumped off and rolled them down the trails leading to Fairfax behind the Deer Park Villa. All before it became illegal and before racing started. The hardest part of the sport was finding someone to drive the truck down the mountain since everyone wanted to go down by bike. Sometimes we had to get someone to drive back up to get the truck back.

Great article. If you’re interested in the story, please check out my feature-length documentary, Klunkerz. I wrote/directed/produced the film that traces the early roots of this fantastic sport. It’s available through my Klunkerz website.

Ride on,

Billy Savage

www dot Klunkerz dot com

Any avid collector must check out Lowkeymotors.com and their collection of vintage “clunkers”. It’s nestled under Tam and you may just bump into many of the ladies and gentalmen in the above article.

Check it out! This is an amazing collection.

http://abclocal.go.com/story?section=news/local/north_bay&id=8044459

Wish I could have been there, but I was out in the desert racing motorcycles. Great story and pictures.

In 1968 my brother and worked at Yosemite national park,and we would get bikes at the rental shop walk them up the bridle trail and ride them down as fast as we could .That was when I started mountain biking,and enjoy it more now with a much better bike

Early 70’s, I was a kid in Wollongong, Australia. Mates and I used to spend half a day pushing our clunkers up into the mountains behind the city. No trails, just the bush. Then we’d spend half an hour tearing back down. Coaster brakes only, occasionally the chain would fall off, that’s when it got real interesting.

I’d guess kids did it all over the world. But kudos to these guys for developing the sport.

What a great article about these young west coast guys (and gals) tearing up the trails!

As a teenager in late 60’s and early 70’s in Virginia beach, a lot of the guys here fixed up their old Schwinn’s into “boardwalk cruisers”. I was into going fast on inexpensive 10 speed road bikes..In ’75 I rode my Falcon 10 speed from Virginia Beach to the other side of the continental divide in Rocky Mountain National Park, camping out along the way..

The 1970’s were a lot of fun for us long haired boys!

Right now I’m in the middle of restoring my 20 year old, Gary Fisher Wahoo MTB..

It’s almost done! Just waiting on the new Schwalbe’s to arrive in the mail next week!

Keep on Pedaling!

I remember my firtst ride into the lower Sierra’s early 80s . We rode into the Needles fire lookout tower. With rucksacks full of climbing equipment, lunck and water.

We hiked our bikes up to the top of the tower for safety and took off to climb.

Greg rode a BMX type (I think) , I had early Stump jumper and Jim rode my modified beach cruser that was the reason for spending alot more for a real Mt bike.

Greg later had a picture of Jim and I grace the front cover of Climbing magazine. We were standing looking at the Needles for the first time. One of Gregs many cover photographs gracing different climbing magazines.

Climbing was always first but that ride rivaled the scene in star wars racing through the redwods.

As we flew down the mountain through giant sequoias riding almost equaled perhaps eclipsed for the moment rock climbing.

It was a incredible experience to open the doors to many more.

Thanks to all the early innovators recognized and not for giving us another way to enjoy the outdoors.

those guys are so cool riding those rigid bikes down those rocky trails

It is so funny when I hear Gary Fisher invented Mt biking. Kind of like FORD invented the automobile. He definitely should get credit like FORD for the first production of MT bikes. Like other people, our neighborhood started riding 5-10 speed bikes up and down our MT trails and racing each other to the bottom with jumps, late 1960s-early 1970s. Yes, we needed someone like Gary Fisher to help make MT biking better. Custom making a good bike was very hard back in the day.

Well I first rode a SCHWINN built “LA SALLE” same as an “EXCELSIOR” which I still ride to this day! Iv’e had it since the ‘70S! Through the years I have collected about 30 bikes or so! And refuse to stop 🛑 riding them! What a great 👍 time to be a kid! I now am 58 going on 16! And DANM proud of it!!!!